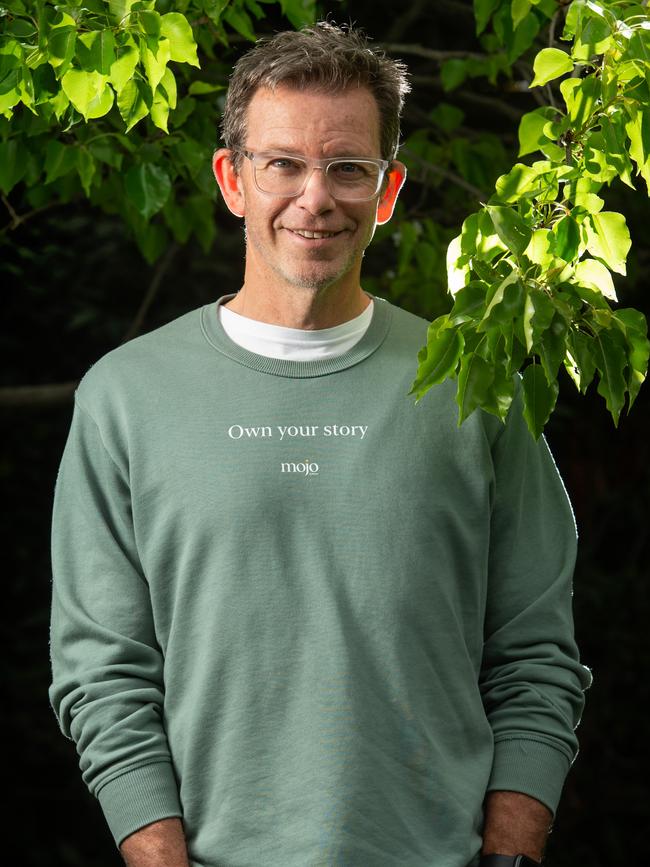

Hamish McLachlan: How life coach Ben Crowe helped Ash Barty reach the top

Mindset coach Ben Crowe says his mission is to help people find their best self and achieve powerful things - and he's helped shape Ash Barty's killer attitude, to tennis and life.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

If you follow the Richmond Football Club, you might know of Ben Crowe and be thankful for the work he did with your captain and coach.

If you’ve watched Ash Barty play at the Open, you might have seen Ben supporting her courtside in her players box.

Ben doesn’t like the terms, but he gets referred to as a life coach or leadership me ntor. He has an ability to help people find their best self and achieve powerful things as a result.

We spoke about his work, Nike founder Phil Knight, learning the power of storytelling, the freedom you feel when you embrace your vulnerabilities, finding your purpose, and his desire to have people feel they “are enough”.

Hamish McLachlan: You theoretically studied philosophy, anthropology and literature at university. You got a degree, but more importantly, met your wife.

Ben Crowe: I met my wife, Sally, through a couple of girls at Monash University who used to give me their notes in all three of those classes, so there was significance to that degree after all!

HM: Have you used any of the disciplines you studied?

BC: You can only join the dots looking back on your life, and I didn’t realise it at the time, but one’s the study of human behaviour and one’s the study of wisdom, but it was the study of storytelling in literature that I had a particular fascination for.

HM: You joined Nike early in your career — as a company, they have had a great ability to tell their story well.

BC: That’s when it got exciting for me. I began to understand the power of human storytelling, of metaphor and analogy, but also, the power of the emotional connection that came with Nike’s story, whether that be with Air Jordan, Just Do It or Livestrong. The best storytellers are those who know their own story first, but most athletes don’t. And it surprised me how interested I was in helping athletes understand their own story, in order to just become better people. That has led me I guess on this journey for the last two decades.

HM: When you left university, what did you actually want to do?

BC: I had no clue! A good friend, Jason Richardson, was working at the Australian Hockey Association as the administration manager and said there was a job going as the media and promotions manager. I got it. My job was to write stories and find ways to elevate the promotion of the sport. They cut Jase and I an enormous amount of slack to trial new things. This is 30 years ago. We created a national hockey league, we changed the name of the men’s team to the Kookaburras, and we started to promote individuals. We got some sponsorships with Nike, and that’s what led to my career with Nike.

HM: You started with Nike in ’93 … what was your remit?

BC: The goal was to make Nike locally relevant. Our team were in charge of identifying, signing and then leveraging talent. Talent could be a team, an event or an athlete. Mona (Steve Moneghetti) had been signed globally so Cathy Freeman was the first local athlete we signed. Shane Warne was the second, Wayne Carey was the third and Lleyton Hewitt was after that. The job was about telling their stories to create differentiation and bring out their personality and have people connect with them, and with Nike as a result. Nike’s growth, not only in Australia, but worldwide, throughout that time was quite phenomenal. I then did the same role for the Asia-Pacific region and took up a global Olympics role at the same time.

HM: You spent a lot of time with the founder of Nike, Phil Knight.

BC: Luckily for me, Phil loves Australia, and Phil loves athletes. He’d come down to Australia for the Australian Open, and he’d want to travel around Australia, and spend time with athletes. By virtue of his passions, I was lucky to spend a lot more time with Phil, his wife, Penny, and his kids than my role warranted.

HM: You had an interesting flight with him?

BC: My first trip to the US was to the Lipton tennis tournament in Miami. There was a dinner for a few Nike people and I was asked along. At the dinner was Phil Knight, who I’d met a couple of times; Michael Jordan’s mentor, Howard White; Andre Agassi and Brooke Shields; Pete Sampras and his girlfriend at the time, Delaina; and me. Who was the duck out of water at that dinner? Phil said to me, “When are you going back to Australia?” I said, “Actually, I’m flying up to Portland tomorrow, to the Nike headquarters.” He says, “Same. Do you want a lift?” The next day I arrived thinking, “I have no right to be on this private jet!” I get on the plane an hour before he did. I ask the stewardess, “What do I do? Where do

I sit? What do I say?” She says, “Relax. Just sit there, he’ll sit over there, and Penny will sit there.” He gets on, and then he takes his shoes and socks off as we’re taking off. I thought to myself given he had spent so much of his career in Japan it must have been out of respect to Japanese custom, so I quickly took my shoes and socks off and put them comfortably to the side. Then I look over, but now he’s got his shoes and socks back on! It turns out he was just scratching his feet! He’s looking at me, his wife’s looking at me, and everyone’s thinking “You bloody Aussies are a crass group of people!”

It was a seven-hour flight, but he and Penny took a real interest in me and my career. After I left Nike I stayed in contact, and we’ve stayed in contact ever since.

HM: Phil took on a huge market and ended up on top. Is it because he’s done what you know is essential, and been able tell the best story?

BC: Absolutely. What I’ve taken from Nike into my own work is the power of purpose and the power of storytelling. Nike’s purpose is effectively Phil’s purpose, which is to bring innovation and inspiration to every athlete in the world. If you’ve got a body, you’re an athlete, and Nike would innovate through product development and inspire through athlete storytelling. That became their competitive advantage against the Germans, Adidas, Puma — the more rational. Nike was completely irrational, anti-establishment and emotional.

HM: And that’s where you play now — in the “emotional”.

BC: I do, yeah. Phil knew intuitively that there’s no rational reason anyone loves their favourite song, or their favourite movie, or their favourite athlete. It’s an irrational, emotional connection that comes with the story. He understood the disruptive tendencies of, for example, creating a black basketball shoe, knowing that in all likelihood, the NBA would ban it. They did.

He was very much counterintuitive, provocative, in order to test the emotional connection. Just Do It — is just an attitude. Just do your homework. Just ask her out on a date. Just do exercise. Phil’s passion around teamwork also became one of Nike’s core values, because he learnt from his running career that you run better in packs.

HM: You spend your time now working closely with people and — these are my words, not yours — helping them become the best and happiest versions of themselves.

BC: Maybe “better” and “happier” versions because you can always grow. Before I left Nike, I spent two days at the Peak Café in Hong Kong, trying to work out my life purpose — my “why”. I remember writing, “I just want to help athletes do things better and be better for it.” I had no idea what that meant, and I had no idea how I was going to do that, but that really lit me up in terms of my “why”. Then I thought to myself, does it have to be athletes?

HM: And now you are helping anyone that needs help?

BC: Pretty much. My “why” hasn’t changed over the last 22 years — it’s kind of stayed the same. I like understanding stories and helping people and that’s led me to where I am now, I guess.

HM: How did you start helping people?

BC: When I came back to Australia, there were a couple of defining moments. One was with Stephanie Gilmore in 2010 after a drug addict randomly attacked her outside her apartment. She went off the tour for a period and I was asked through her connections to work with her. The process of helping Steph find perspective and purpose, connecting with herself and her goals, and observing her grow and get back to her best was incredibly rewarding.

HM: And since, you have worked with some of Australia’s highest-profile athletes and teams and seen them scale new heights.

BC: It started pretty casually — whether it was Leon Cameron, or Clarko (Alastair Clarkson), it was all just as a hobby and a friend more than anything. The big change came in 2016. I was working with Peggy O’Neill, and had done work with Brendon (Gale), and agreed to work with Trent (Cotchin) and Damien (Hardwick) as well.

HM: What do you work on when they come calling?

BC: With Trent and Damien I tried to help them find their authenticity, and allow them to embrace vulnerability, to celebrate their imperfections and find purpose and meaning — to find their story, I guess.

HM: How do you measure your success?

BC: Great question. My KPI is how they turn out in five to 10 years as a human, because you’ve got to be a good human first and a good athlete second. Don’t get me wrong, I love it when someone achieves their professional goals, but I love it more when Trent Cotchin and Damien Hardwick start connecting with themselves as people, not just as coach and captain. Off the back of that, it was the same process with Cricket Australia and their leaders, or with Ash Barty, watching her go through a similar process, and Dylan Alcott more recently — it’s all incredibly rewarding. And while I’m rapt that they’re winning, in terms of success we won’t really see it for five years after they retire from their sport, what kind of human they are, what kind of husband or daughter or brother or sister they are.

HM: It’s much more than just winning.

BC: Much more. They need to find fulfilment, not just achievement, because the sports industry is littered with people who have achieved, but they’re not fulfilled. They’ve found confidence on the field, but not that happiness off it. They are so distracted by the persona of who they are that they forgot the person. Achievement without fulfilment is that ultimate failure. We don’t just want to perform better. We want to retire better.

HM: I’ve heard you say you think there’s two types of people on the planet today. Who are they?

BC: 3,2,1 is what I’m going with, Hame. I think there’s three types of confidences, two types of people, and one thing we’re all in search of. The three types of confidences: in yourself, in your journey, and in your performance. The two types of people are those who see vulnerability as a strength versus those who see it as a weakness. And the No. 1 thing on the planet that everyone needs, deserves and craves is unconditional love. It’s a love without any conditions, which means you don’t have to do something, or achieve something. You can just be. To be enough, to be worthy, to be loved.

HM: Is it all a confronting process for the subject, whether that be Trent or Damien or Ash Barty?

BC: Very. It’s probably the most courageous journey anyone will ever go on, but the most rewarding. It’s the journey to find out who you are. You realise that your life story is not your life, it’s just your story, and you’re the author of it. The good news is, you get to write the ending. The people I work with also get to go back to crucial moments in their lives when they perhaps told themselves they weren’t good enough, or smart enough, or loved enough. And then they reframe it. We realise it’s not the experiences of our life that determines our life, it’s the meaning we put behind the experiences, and the stories we tell ourselves.

HM: Powerful for them, but it also has a rub-on effect with those around them.

BC: Definitely. If they can create safety or permission for others to be more open and imperfect the connection between them goes to a whole new level. So does the humour and lightness. You’re one of the best I’ve seen in this space, Hame. My job is to put a mirror up to someone, and through pattern recognition help challenge a perspective, but they do all the heavy lifting in the relationship. They have to not only embrace all their imperfections, but celebrate them, and take ownership of their life story, and from that place, they can show up in the world and let go of the “not enough” stories that they told themselves previously, and separate their self-worth from their roles. The freeing up of that is extraordinary. It’s a process that’s incredibly liberating, but counterintuitive to males and stoic Aussie alpha males, who would rather keep the mask on and the armour on. That’s why I’m in awe of Trent and Dusty and Dimma for doing in 2017 what is incredibly counter intuitive among Australian males. They’ve seen the benefit of that, not only in a professional sense, but very much in a personal sense as well. That’s my goal, where possible, to share some of those principles with the wider world. If Trent can teach young teenage boys to embrace vulnerability, or Ash Barty can teach young girls to celebrate imperfections but follow your dreams and stay true to yourself, or Dusty, or Andre, the impact won’t just be on the field for those who follow those sports, it will be quite profound off it.

HM: The one thing that I’ve noticed with Cotch — I don’t know Dimma as well — and what I observe of Ash, is that they are all affected less now by “external noise”.

BC: Yeah, they don’t define themselves by what they do. It’s more about who they are. Separating the person from the persona and separating their self-worth from whether they win or lose a game definitely helps. So does identifying distractions and accepting the things you can’t control. When you let go of caring what people think about you but you still care about others, you have all the power.

HM: The great part about all of this is historically you’ve worked with CEOs, professional athletes, high-level coaches, but now you’ve decided to pivot, broaden, and teach the youth, the younger minds.

BC: Year 12 kids are my focus this year. My heart goes out to them. More broadly, the itch I can’t scratch is the age at which kids are taking their lives, and the emotional health of adults. I’m not a trained psychologist or doctor — my work is more life and leadership principles — but I’ve found there’s still a lot of wisdom that can be shared.

HM: You got a phone call last year that confirmed what you were doing was helping.

BC: It was a voicemail, actually. The vice principal of a school, crying into the phone about a mum who’d been in her office crying about her daughter. I just wanted to teach the girls two things. Call bullshit on perfectionism, and tattoo “I am enough” on their souls, and have a series of words they could draw down upon if nervous before a test or a race. One girl came home from school that day and said, “Mum, do you know that I am enough?” The mum said, “What do you mean?” She said, “I’ve just realised that I’ve been comparing myself to all these other girls, and I don’t want to do that anymore. It makes me feel like shit. I’ve just realised, I’m enough.”

The mum turned around, started crying and said to her, “That’s what I’ve been trying to tell ya!” She got off her medication, and was then going to school and getting involved in extra-curricular activities. That’s given me a sense of excitement, that these principles aren’t just exclusive to elite athletes, CEOs and so forth. They can be shared with the whole world. That’s why I’m keen to help year 12 kids this year, to see how these principles work against the biggest distraction the world has seen.

HM: You are helping people become happy. Are you happy?

BC: I am, very. 2019, was one of the most fulfilling years for me professionally and personally, and it was the gap year where I found my passion. Not dissimilar to Ash Barty taking a gap year in tennis to work out who she was. I feel that I’m in my sweet spot at the moment, in terms of that balance between motivations and strengths. We all suffer from impostor syndrome at times, Hame, but when you realise that everyone is just totally winging it, that life is really just a work in progress, an experiment, full of uncertainty and wonder. Based on that, life becomes this beautiful adventure with no expectations. It’s taken me 52 years to work that out and what I want to do when I grow up. I’ve found out what I want to do with whatever time I’ve got left, and that is impart these themes. That purpose that I tried to articulate 22 years ago hasn’t changed, but how I do it has, and I guess I needed to go through all those other journeys to get to where I am now. I’m hoping there’s still a few chapters left.

HM: You’ve helped an enormous amount of people, including me, and I’m sure you’re going to help out an enormous amount more. Thank you.

BC: My pleasure, Hame. Thank you.

Ben Crowe is running a virtual confidence masterclass on September 29 for professionals, students and athletes on perspective, connection & purpose. DETAILS: mojocrowe.com

READ MORE:

MARK OF THE CENTURY STAR WINS $1.4M HEAD KNOCK PAYOUT

VICTORIA’S MOST EXCITING REGIONAL INNOVATORS REVEALED

SHEEDY, ROYALTY, BOMBS: NOTHING ORDINARY ABOUT ‘AVERAGE COPPER’