Anzac Day 2023: Honouring Victoria’s veterans

Across the state, veterans from World War II to the most recent conflicts will come together to mark Anzac Day. Meet some of those heroes here.

Leader

Don't miss out on the headlines from Leader . Followed categories will be added to My News.

From inner-city Melbourne, to the most far-flung outposts in our state, veterans are set to come together on Anzac Day to remember the fallen and their own sacrifices. To help mark the occasions, we spoke to veterans from across Victoria to get a sense of what the day means to them and to reflect on there own memories of the battlefield.

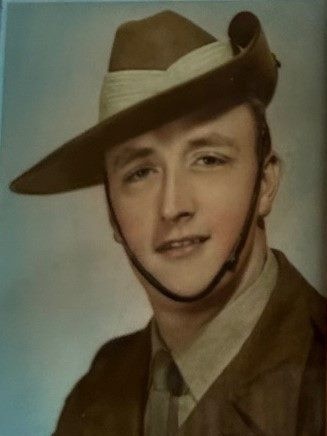

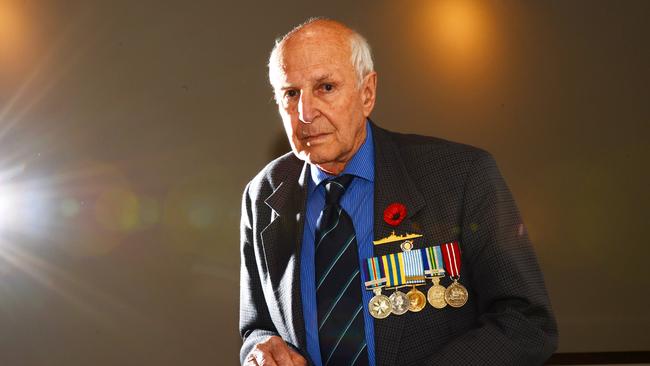

Duncan Mackinnon, Hastings

He was just 13 when he lied about his age to land a job as a deck hand on a ship that would eventually take him to war.

Duncan Mackinnon’s family was plotting to return to Australia from the UK in the late 1930s and the youngster decided to join his brother Donald on the MV Melbourne Star when she left Tilbury docks in London.

The ship was a refrigerated cargo liner designed to ship frozen meat from Australia and New Zealand to the UK

She went on to play a critical role in relieving the siege of Malta in August 1942.

“I was at school in Scotland at the time and I went down to London and pretended I was 16 to get the job on the Melbourne Star where my older brother Donald was and we set off for Australia in 1938,” Mr Mackinnon said.

“Mum and Dad wanted us all to move back to Australia because they were worried there was a war coming.

“The plan was to jump ship when we docked at Sydney, but that didn’t happen and 18 months later we were in a convoy of ships being bombed.”

Despite his peril Mr Mackinnon said at the time he was more worried about ongoing sea sickness.

“I was scared stiff. The sea sickness, the risk of being washed overboard; which nearly happened several times, was a more immediate threat to me as a young boy.”

MORE ANZAC DAY COVERAGE

Mate’s final words before boarding ship to hell

How to commemorate Anzac Day in Victoria

Mr Mackinnon said a treacherous trip to Malta from Nova Scotia as part of Operation Pedestal was etched in his memory.

“Our convoy of 18 ships were bombed and torpedoed by the Germans and Italians around Malta, all the way, every day and night.

“The Germans dive bombed with the Junkers Ju 88 planes, E-boats attacked the convoy until there was only five boats left.”

The SS Ohio oil tanker — requisitioned by UK to resupply the island fortress of Malta — came under fierce attack and was in danger of sinking before reaching the harbour.

“The water was all ablaze due to leaking oil from the Ohio and the Melbourne Star went through the flames and burned the paint off the ship,” Mr Mackinnon said.

The Ohio was so badly damaged she never sailed again and was scuttled off Malta.

By 1941, Mr Mackinnon was ready to heed his mother’s plea to come home.

“She had three sons at sea at the same time and couldn’t bear it anymore.”

After jumping ship in Sydney Mr Mackinnon caught the Spirit of Progress Steam Train to Melbourne to begin his new life working for General Motors.

However, within a year he had joined the Australian Imperial Force and was learning jungle warfare to prepare him for action in Papua New Guinea.

“There were a lot of battles against the Japanese but the most fearsome of all was Slaters Knoll,” he said.

“The Japanese had a 34,000 strong garrison and we had to take this strategic hill to enable us to overlook the enemy.”

Mr Mackinnon was discharged in 1946.

His brother Donald did not return from the war.

He was killed when the MV Melbourne Star was torpedoed by U-boats off the Bahamas in 1943.

There were 115 lives lost and just four survivors.

Mr Mackinnon will lay a wreath for all mariners at the Hastings cenotaph on Tuesday.

“It’s a day of memories. I think about everyone who didn’t come home,” he said.

“There’s not many of us WWII veterans left now. Frankston RSL, where I’m a member, has 40.

“I’m 99 now. I reckon I’ll make 100, no worries. But when we’re all gone, we need those left behind, the young ones, to honour the sacrifices made by the fallen.”

Brian Slocombe, Melton

It was the overnight guard duties that terrified him the most, he could not see his own hands and it caused the hairs on the back of his neck to stand up, for hours and hours on end.

The nightmares began during the war and they have never left him.

Brian Slocombe described parts of his service in Vietnam as trying to sleep when there were armed burglars in your home — you could never rest.

Although he agreed to share his experience, he said the focus should not be on him or the other survivors.

“The blokes who should be written about are the blokes who never came back”, Mr Slocombe said.

“I don‘t like to glorify what happened to me because I’m still alive and I’ve got a family, many didn’t come back and plenty who did were never the same,” he said.

But Mr Slocombe’s story is compelling.

After months of replacing casualties on different missions, he was tasked to join Operation Massey Harris, described by historians as a “miracle”.

On the first day of the Operation, he was driving an Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC) when it hit an anti-tank mine which blasted the heavy vehicle almost 3m in the air.

The blast killed the South Vietnamese bushman who was scouting for the squadron, affectionately known by Brian as ‘Nigel’.

It wounded 14 Australians and one New Zealand soldier, but it could have been so much worse.

In the days before, engineers fitted the APC with an armoured plate that rested underneath the vehicle, referred to as “up-armouring”.

Mr Slocombe recounted that when engineers were explaining why they tipped the vehicle on its side to fit the plate, all he was thinking about was a well-earned break and a drink back at base.

Thankfully, the mine exploded underneath the diesel tank which, aided by the up-armouring, protected those on board and reduced the potential of further injuries.

Mr Slocombe was flown with head, neck, and stomach injuries from the explosion.

He spent three months in hospital after the explosion but needed medical treatment for a long time after that.

His stomach has never recovered and he still can’t digest any form of spicy food, even pepper, without causing him to become extremely ill.

After the living nightmare of Vietnam, Mr Slocombe swore he would never go back but he has returned in recent years with his family.

It has only been in recent years that he felt comfortable bringing out his medals, let alone marching on occasions such as Anzac Day, such was the public sentiment towards Vietnam Vets for a number of years.

A moment that never left him was the day he was walking along the street when a gorgeous woman approached him before spitting on his face and calling him a “baby killer”, such was the outrage directed at soldiers during that time.

Mr Slocombe lost a lot of good mates during the war and in the years that followed.

For him, Anzac Day is a time to remember the fallen and to reflect on the loss of their families.

Graham Docksey, Albury

Graham Docksey was just 19 when he was deployed to Vietnam in 1966.

With both his parents having served in the army during the World War II, Mr Docksey said he was always influenced to serve his country.

As a young infantry soldier in Vietnam, Mr Docksey described his experience as “big adventure”.

“Any chance to blow a tree up or blow a road up or something like that, It‘s pretty good (for a young boy), but it gets mixed up with a lot of sad stuff. which you might have done as a 19-year-old but as a 75-year-old you wouldn’t and think that’s wrong,” he said.

Being in the conflict area meant Mr Docksey sometimes went on operations for weeks without a shower and socks.

Mr Docksey said the most significant thing he remembers from his time in Vietnam was the camaraderie between soldiers.

“It’s going to make me emotional, but the camaraderie it‘s something unique that only a soldier can share with another soldier,” he said.

Mr Docksey recalls how after a long operation or day, everyone would head to the bar but said it was a “dangerous combination”.

“You’d have a meal and then open the bar up, which was simply a 44-gallon drum with the cans of beer in there. And that was how they expected us to debrief,” he said.

“There was no psychologist to come along and sit the table and ask, ‘how you‘re feeling, son?’ You know you did something two weeks ago that may have been distasteful, but how are you feeling about it today, we didn’t have that.”

Today Mr Docksey suffers from PTSD, which his wife helps him overcome.

“I‘m still teaching her to ensure I can see where she is because sometimes she walks up alongside me. I’m startled because it reminds me of being on patrol. What’s interesting is even after all the time, the simplest sound of a crack of a tweak gets me,” he said.

“The good thing over the years now is that my wife and I can cuddle each other at night, and I‘m feeling safe, and she’s got my back.”

Mr Docksey served in the army for 46 years and only got out after he “couldn’t do it anymore.”

“I was in my early 60s, and I’d get down on the ground and fire the rifle that I couldn’t get back up easily. I had surgery which resulted from parachuting, jumping on the back of trucks, carrying other soldiers on your back, all those silly things we used to do, which today occupational health and safety would not allow you to do,” he said.

After almost five decades of service, Mr Docksey continues to give back to the community, serving as the president of Albury RSL sub-branch.

“The number of soldiers walking around now with mental health issues, it‘s terrible. But, we veterans, you gotta look after each other,” he said.

John Haward and

Andrew Guest, Box Hill RSL sub-branch

Anzac Day brings back many memories for John Haward and Andrew Guest — even if some of them are a little hazy.

Both men were in their early 20s when they were sent to Vietnam War in the 1960s, with Mr Haward serving as trooper and Mr Guest as a artillery officer, based in Phuoc

Toy province.

Mr Haward, 75, turned 21 while overseas, and after he received a bottle of scotch and a fruit cake from his family, he was determined to not let the occasion go quietly.

A group of his mates got together in his tent and got stuck in to “a bottle of Bacardi that we bought from the Americans” and some beers which they’d stashed under the tent.

“We hadn’t drunk spirits for a long time so we got pretty boozed, and we’d run out of coke so we were drinking it neat,” Mr Haward said.

Just as he was pulling the cork on the bottle of scotch, his crew commander walked into the tent, screaming at the group of six and threatening to put them on charge.

Mr Haward said one of his mates then yelled out: “Len (the crew commander), do you realise it’s Johnny’s 21st birthday today, and that’s a bottle of scotch his father sent over from Australia with the birthday cake.”

The crew commander stormed out of the tent, and the group feared they were in deep trouble.

“About 10 minutes later, he’s come back in, and put another bottle of scotch on the table he got from the Sergeant’s Mess,” Mr Harward chuckled.

Along with nursing a sore head the next morning, Mr Haward was left reeling from a painful injury sustained during the boozy celebrations.

“I was laughing so much I fell back in the chair, and there was a steel bar that goes across all of the tent, and it went straight up my back and took all the skin off,” he said.

“I never felt a thing that night, but the next morning, my god.”

Meanwhile, Mr Guest, 77, recalls getting his hard-earned beers nicked on Christmas Day after he had to drop everything and rush onto guns duty.

“The Vietcong broke the truce just as I was sitting down to have my special lunch,” he said.

“I had to leap up, run and do my thing on the guns, and my lunch went everywhere.

“When the firing was over and we got back to normal, I went back to find my lunch covered in flies, ants and dirt, and some bugger had pinched my two cans of beer.”

Today, the two men serve as president and secretary of the Box Hill RSL sub-branch, and bar staff arranged for the duo and the Herald Sun to enjoy a Bacardi and Coke to bring back the memories of Mr Haward’s unique celebration.

Mr Haward later said it was the first time he’d had Bacardi in more than 40 years.

He might even have another one after the sub-branch’s Anzac Day Dawn Service, to be held at its cenotaph from 5.30am on Tuesday.

The duo said the sub-branch was looking forward to having a proper ceremony this year after their usual commemorations were impacted in the past three years by Covid-19 restrictions.

“It’s the one day of the year that I set aside everything else,” Mr Haward said.

“It is a day of remembrance … I lost one of my very close mates who was killed over there, and when they sound the last post on Anzac Day just on dawn, I remember my close mate and all the other guys that didn’t come home.

“They talk about heroes coming home from war, but the ones who didn’t come home, they’re the heroes, and that’s why we’re there on that morning, to remember them and never ever forget them.”

Donald Orr and Daryl Ryan, Werribee RSLsub-branch

Donald Orr was told to hop off an overflowing truck, filled with 18 of his fellow battalion members, and get on the next one.

The truck he got off, as well as another nearby, was “blown sky high” killing 36 people.

Orr’s truck, the third in line, was the only one standing.

“It was our first operation we were going out to as a battalion … there were more than 30 people in our unit that never got to their first major conflict before they were taken out,” Orr, a member of the Werribee RSL, said inside the club’s dining area.

“That’s the way it was”.

Sitting across from Orr is long-time mate and fellow Vietnam national serviceman Daryl Ryan.

Ryan, a 50 year member of the Werribee RSL and its president, reflected on a 35 day stint walking through enemy territory with barely a whisper uttered or cigarette smoked at the risk of giving away his location.

“You were lucky if you spoke two words to the bloke in front of you,” he said.

“We never wore aftershave or anything out in the bush because of the smell. Some of the areas you’d go into there’d be no smoking and everyone out there was a smoker, because you could smell it”.

Both men were conscripted in their early 20s.

Both men served about five months in 1969.

And both men spent most of their time in the jungle.

But, as every returned veteran would tell you, no two experiences in war are ever the same.

Not even for these two great mates.

One of the things that “bugged” Orr about battle was the various rules agreed to between countries soldiers had to follow.

“As an example, one night we were lined up on the sea shore in ambush position and not much further than a kilometre offshore there were four or five enemy sampans in there with soldiers but because there were fishing vessels that may’ve been between us we weren’t allowed to fire on them,” he said.

“We had to wait until the enemy came in to land and you had to have a fire fight or leave before they came because we were outnumbered.

“It was very hard to differentiate between civilian and soldier because they all dressed alike”.

Ryan celebrated his 21st birthday at Puckapunyal before he was sent to Vietnam on April 22, 1969.

“We were told we’d be doing national service because of the conflict in Indonesia but then we find out it’s Vietnam,” he said.

“I didn’t find out until 20 years after that I had volunteered to go to Vietnam. I didn’t volunteer for anything.

“You had to be a volunteer to go [to Vietnam] but you weren’t told. They just marched us into a hall and they told us that we had to go Vietnam. End of story”.

Despite being based at Nui Dat, Ryan did not see much of camp.

It was in the jungles where he spent most of this time; simultaneously looking for and anticipating an “unknown enemy”.

A lot of the men in Ryan’s battalion spent 300 of their 365 days in the jungle.

He did not get that long.

Some five months after landing in Vietnam Ryan received a gunshot wound to the shoulder from backblast from a claymore mine.

“Injuries occurred within our own ranks, naturally,” he said.

“When you walk into the jungle with a rifle that’s ready to go and you’re relying on that safety catch to work … and some of the weapons would fire 20 rounds as soon as you can blink. So if he accidentally slips and he pulls the safety catch and pulls the trigger it’s 550 rounds a minute.

“You think back now you’re carrying claymore mines, grenades, explosives, rocket launchers and you didn’t think anything of it. You were a pack mule and that’s about it … a walking blasting kit”.

He was sent home on a stretcher aboard a RAAF Hercules to Laverton.

Like Ryan, Orr returned home after five months albeit under different circumstances.

He was offered a chance to sign on for two more years or return home then and there.

“I offered to stay until the end of our tour but was told it was either two more years or go home then … to which I replied, ‘well, there’s your answer’”.

But the horrors were far from being dealt with.

The fear of abuse from the Australian public towards returned veterans was that severe, Orr’s plane of returned veterans landed at Sydney airport “in secret” before they were flown out to their respective capital cities.

“It was pretty much a case of go home and disappear,” he said.

“We came home and you couldn’t wear your uniform in the street. You were abused, spat on called a rapist and baby killer. Everyone knew you were in the army because you had short back and side haircuts and everyone else had long hair and earrings.

“It took a long time, 1987, until we were welcomed home not from a war, because we weren’t allowed to call it a war, but from a conflict”.

A lot of these issues post war still linger for Orr and Ryan, both of whom expressed frustration at the treatment of veterans when it came to claiming pensions and their “deserved rights”.

Ryan said many veterans have struggled to deal with the Department of Veteran Affairs (DVA) and the various forms which “set you up to fail”.

“The hardest part, and even with the veterans today, is what we need to go through to get recognition from DVA … we have to jump through that many hoops it’s not funny,” he said.

“If you put the wrong thing in the wrong sentence you could have it rejected”.

It is all this and the ongoing trauma faced by veterans and their families daily why RSL’s play a significant role in communities.

“If it wasn’t for this place and the likes of Don, I’d be one of those statistics that has committed suicide,” Ryan said.

Peter Thompson, Epping RSL sub-branch

Peter Thompson was called up in 1966 as part of the fourth intake for national service in Vietnam.

He remembered he was excited to go on the adventure.

“We weren’t apprehensive about it, we did all the training and we were quite fit, ready to go,” Mr Thompson said.

After three months of basic training in Puckapunyal, he was part of a supplement of 100 men who went over to replace other national servicemen posted to Vietnam.

Mr Thompson left for Vietnam on April 20 in 1967 and spent 311 days there, coming back in February 1968 to the Watsonia barracks.

“We had great morale among the national servicemen, we were all the same age and went in together,” Mr Thompson said.

“We thought it was our turn.”

He recalls taking part in various operations across the country

“Going out and taking part in ambushes around the province, it was very interesting,” he said.

“I did go on a few roadblocks and things, village searches and that sort of thing, flying around in helicopters.”

Mr Thompson will spend Anzac Day in Warrnambool this year, as he visits one of his friends who served alongside him in Vietnam for the occasion every couple of years.

But he also enjoys going into the city and participating in the march.

“All my local friends and I go, and we have a great time,” he said.

His message for Australians on Anzac Day was one of remembrance.

“Think about the people who didn’t come back and give them respect.”

John Merrett, Epping RSL sub-branch

John Merrett is another Vietnam veteran who is dedicated to Anzac Day and encouraging remembrance.

He served a shorter stint from January to May in 1969 as the twelfth intake of national servicemen posted to Vietnam.

His time was cut short, as unbeknown to him, the battalion he joined was preparing to return home when he arrived to begin his service.

But despite this, he still recalled fond memories.

“I made a lot of mates, a lot of good friends, they‘re friends for life,” Mr Merrett said.

“Over there, your mates looked after you, everyone looked after each other.”

It wasn’t all fun though, as Mr Merrett recalled the less enjoyable parts of the war serving as an infantryman.

“It was hot, sweaty and wet … I was there in the dry season, it was very hot and very hard work.”

“The infantry was the coal face of the war.”

Mr Merrett said one of his favourite parts of Anzac Day was the friendships.

“Catching up with friends … and you get your family together, going to the Dawn Service,” he said.

“And remembering the men and women who went to war and never came home.

“Anzac Day is a very important day.”

“I hope there’s never any more wars (but) I'm proud I served in the army, I’ll never forget that.”

David Manning, Glen Waverley

David Manning remembers the culture shock of his time spent on two peacekeeping missions in the Western Sahara and East Timor.

For a boy from Glen Waverley, the appearance of this airport in Western Sahara was a world away from what he’d grown up around let alone the flock of flamingoes which he found in a nearby waterway days later.

The mission in West Sahara was simple enough; build relationships with the locals, help where needed on the United Nations’ Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara. In the background, Western Sahara was going to have a referendum to choose between independence and integration with Morocco.

Mr Manning likens his new surrounds to a scene out of a James Bond film.

“It was just covered, there was sand everywhere, just like you see in the movies, it was unbelievable, it became really beautiful to see these pink flamingoes everywhere,” he said.

The heat was high in the West Sahara and trying to procure goods like butter and cheese — basic staples at home — where almost impossible to find in his new city.

Especially because Mr Manning found himself being tailed by the Moroccan secret service.

“I noticed that every time I went into a shop, there was a man in a suit following me and it was the secret police,” he said.

“Everyone was spying, I think the only people who weren’t were the Canadians and the Australians. There were nights where I’d play some music in my room and walk down to the lobby and the secret police would be singing the song I had on, they had my room bugged.”

The mission has given Mr Manning a sense of adventure and, more than a decade later, he found himself once again in unfamiliar surroundings in East Timor in 2002. He was serving as part of the United Nations Mission of Support in East Timor as the UN helped provide political stability to the country which had become independent.

The task was simple enough, stay friendly with the locals, help maintain peace in the area, train the local police and help out where he could.

The scope of that help was vast. From helping police local crime to uncovering a mass grave created by local militia to trying to helping teach English and provide medical supplies to locals, Mr Manning was the area’s Mr Fixit.

“I was living in the jungle with one other Australian and two Mozambique police officers, it was like this bamboo village,” he said.

“I still keep in contact with them too … it was great meeting other cultures and learning about other cultures.”

Those two trips have changed his perspective as he readjusted back to life in Australia but he still reflects regularly on his time overseas despite almost two decades passing.

“When I came back from Western Sahara, because there are lots of unexploded mines there and they couldn’t find them so you take your chances when you walk off the road, someone would say ‘let’s go to the oval’ and I’d walk the long way round to the path,” Mr Manning said.

“There were just these habits you got into and the way you spoke to people … it was just such a culture shock (coming back).

“I’ll still see something that will make me think back to the times over there or if I see something on the news about East Timor or Africa and that’ll take me back.

“There was some tough times, in East Timor I was eating dog at one stage just to get some red meat, but you also had a lot of good times with the locals and a lot of fun with the locals and some teary times as well.”

Mr Manning said Anzac Day bears a special significance for him, not only because of his service, but also because of his families’ ties to the day.

Mr Manning’s eldest daughter Carrie served in the navy while his youngest daughter Brianna is currently serving in the navy and will march in Melbourne’s parade. Mr Manning’s brother Paul is also serving in the army while their dad did national service.

“It’s a day of reflection for me on the time I served overseas and of the other people who served overseas and in the different wars … and the people who you served with who have since died,” he said.

“It’s great that my kids are taking up what I had so much value in, not just serving the country but trying to make a difference to the world and world peace.”

Chris McAleer, Kilsyth

The simple act of getting outdoors with good company and fishing rods is helping young veterans rediscover mateship and camaraderie when they return home from service.

Veterans for Fishing was created by Kilsyth’s Chris McAleer, who served on a peacekeeping mission in the Solomon Islands in 2013.

He formed the fishing group about six months ago, after realising trying to get younger veterans involved in the RSL was quite difficult.

“They just don’t feel like they fit in,” he said.

“I started Veterans for Fishing as a way to get younger veterans involved with other veterans but also for those veterans who aren’t doing so well.

“We’re using fishing as a form of therapy and mateship and introducing them again to that mateship and camaraderie.

“It’s putting veterans in touch with other veterans and creating a community.”

Mr McAleer has taken veterans and often their family members too for fishing trips around the state, casting a line at Lilydale Lake and the Goulburn River.

The veterans have served in various conflicts including Iraq and Afghanistan.

“It’s not always about the fishing it’s the scenery as well,” he said.

“You’re not sitting in a bar, you’re out in nature and it’s a relaxing thing and you can unwind.”

Mr McAleer completed a mental health first aid course before starting the group.

“I had a few issues when I left the defence force myself which is why I really started it,” he said.

“You feel like you’re part of a family (when you’re in the force) and when you leave it’s like there’s something missing.

“It’s like someone has taken something away from you and you do feel out of it.”

He said on a recent fishing trip, despite the terrible weather, the group laughed the whole time and had a great day.

“It created that camaraderie again.”

Veterans for Fishing has become an independent sub-committee of the Mt Evelyn RSL sub-branch.

Mr McAleer was part of the very last rotation to be deployed to the Solomon Islands on a peacekeeping mission.

The deployment did a lot of pack up work and training in the jungle and also helped communities rebuild, including assisting one village rebuild a road that was washed out by floods, pulling rocks out of the river by hand.

Mr McAleer said he loved spending time with the local kids and helping out,

He reflects on the time he served each Anzac Day and remembers all those who served our country.

“For me Anzac Day is about the soldiers who came before me,” he said.

“The men that laid down the road so to speak, our forebears, the guys that really set in stone our Anzac spirit.

“For me I like to reflect upon that, and now they’re not here anymore I’m representing them as well.

“I know each soldier is a little bit different on how they think about it but that’s how I reflect on it — I’m now a custodian of traditions that I want to pass onto the next generation.”

Tony Geyer, Warrnambool

Warrnambool RSL senior vice president and military compensation advocate Tony Geyer served in the army for 38 years — including a stint in Kandahar, Afghanistan.

“We were based as part of a divisional battle group at the Kandahar airport,” he said.

Mr Geyer started his journey in September 1980 as an army reservist soldier and was commissioned as an officer in 1996, transferring to the regular army in 2000

“In 2016, I was tapped on the shoulder and told that I was too old to be in the regular army and I transferred back to the reserve for a couple of years,” Mr Geyer said.

“By that stage, the last two years was a real struggle for me to get the enthusiasm to remain in the army and I asked to apply to resign my commission and step away from the army.

“That’s the way life goes.”

“I loved every second of it — but live moves on — when I did leave the regular army we sold our house and built another house and my life changed direction,” he said.

Mr Geyer said when he first joined the army reserves he was serving as a police officer.

“The army reserve was a break away from the pressure and stress of the police life,” he said.

He said the adjustment from working in the police force and then joining the army reserve enabled him to explore other career opportunities and found it “incredibly relaxing”.

On Anzac Day last year, My Geyer was in Townsville at a reunion with some former army friends.

“Last year was an opportunity to renew those friendships and acquaintances and there’s some I haven’t seen for 25 years – I thoroughly enjoyed every second of it,” he said.

“That particular Anzac Day, on reflection is all about renewing those friendships — which for most for servicemen, Anzac Day is an opportunity to be with our friends and to think about those who we lost.”

John Palmer, Wonthaggi

John Palmer is 94 years old and has watched on as the world has fallen into conflict time and time again.

An army reservist who joined up shortly after World War II, the Wonthaggi man was used for his construction skills.

He joined the construction squadron, training for many weeks of the year in case he ever got the tap on the shoulder to go overseas.

In 1963 that tap on the shoulder came when Mr Palmer was sent to New Guinea for a two-week tour, building bridges and roads.

“They wanted the married men to come home so they could see their family but they couldn’t just send a plane to bring them home,” he said.

“So we organised a plane to take us over and bring them back.”

“We all got on well together but it was hard working conditions.”

Mr Palmer said even though he was never on the front line he still felt proud he could serve his country by “being ready to go”.

“That was just what we trained for,” he said.

He left the army reserves when he was in his late 40s.

Mr Palmer’s family has long been involved in the defence force, with his dad and uncle serving in World War I.

His son has been a long time army officer and one of his daughters stood alongside Sir Dunlop Weary in an operating room as a nurse.

He said Anzac Day was an important day to “remember all the things that have happened in the past to shape our country now”.

Les Hughes, Dandenong-Cranbourne RSL sub-branch

Les Hughes gave Australia six years of his young life, and continues to give today.

Mr Hughes, 92, joined the Royal Australian Navy at just 19, following in the footsteps of family members who had served in both world wars.

Deployed twice during the Korean War, Mr Hughes spent six years on tour.

Today, Mr Hughes is still a tireless supporter of the RSL and the support it provides to returned service members.

“I’ve been involved with the RSL and I’m involved with the Anzac and the Poppy Appeals,” he said.

Mr Hughes said readjusting after returning from service could be challenging, which was why the extended support by the RSL was so important.

“Being in service, it’s a highly disciplined lifestyle, your life really isn’t your own. You’re at the beck and call of the senior ranks,” he said.

“When you leave the service, you certainly notice the difference.”

Simon Bloomer, Dandenong-Cranbourne RSL sub-branch

Boronia man Simon Bloomer said his older brother had been the inspiration for him to join the armed services.

Mr Bloomer, 74, was 20 years old when his brother was sent to Vietnam.

“I was living in Darwin when my brother John was on his way to Vietnam,” he said.

“He was able to drop in on his way to the air base. I was quite inspired.”

Mr Bloomer did two years of national service spent 11 months in Vietnam.

“I came back reasonably well and returned to my job,” he said.

“I was in my mid-40s when I decided to get involved with the RSL.”

Mr Bloomer said it’s important to continue commemorating Anzac Day for future generations.

“My worry is that we aren’t getting to the younger people to provide the background to why Anzac Day is important,” he said.

“The Australian ethos is built around the qualities of returned service people. It’s looking after each other, mateship.”

Rus Kiellerup, Ballarat

Two of Rus Kiellerup’s uncles were killed in World War I.

While living in the Yarra Valley, he joined the army himself in 1964 at age 18.

He signed up to be a tank driver because it paid better than other roles and ended up in the first armoured regiment then known, he said, as Menzies’ Koalas.

“It was something to do,” Mr Kiellerup said.

“You know, you’re footloose and fancy-free”.

His squadron was in Vietnam by mid-February 1968.

At first, the tanks were considered “too noisy” and “too lousy”, Mr Kiellerup said, but that changed at Coral–Balmoral.

“The squadron assisted the infantry very admirably and after that we couldn’t move without tanks,” he said.

In the end Mr Kiellerup spent 12 months in Vietnam, flying out at one point for R&R on his 22nd birthday.

“If it wasn’t for some of these blokes,” he said about members of Ballarat’s Vietnam Veterans Association, “I probably wouldn’t be here.

“It wasn’t until 1980 we realised something was going on.

“People were starting to talk to each other and say, ‘Oh s–t, I’m not the only one.’”

Bill Dobell, Ballarat

Bill Dobell turned 20 while serving in Vietnam.

His work as a forward scout left him, he believes, with psychological damage.

“That means you go first out in the bush looking for the enemy or whatever it is you’re looking for,” he said.

“As you can imagine it’s fairly highly stressful because they’re looking for you too, but they’re generally lying on the ground looking for you.

“So they’ll see you before you see them, but you’re supposed to see them first if you can. And that is a long day.”

He said being a “grunt” put him under a lot of strain as soldiers were trained to act without thinking and it was difficult to “de-aggress” afterwards.

“When there’s a shot fired, you run at it,” he said.

“You don’t run back, you run at it. Our enemy must have thought we were mad, because they’d fire a shot at us and we’d run at them.

“If we were ambushed, the drill was to turn, face the ambush, and march into it firing. And we did.”

Upon his turn, Mr Dobell was heckled and abused by marchers on Bourke St one night.

He said that although his treatment from other Australians was disappointing, he has received many apologies since.

Having been married now for half a century, Mr Dobell said his wife Marg was responsible for the continuation of their relationship despite his battle scars.

“We did go through hell and back, or she did,” he said.

“I didn’t know it. I was oblivious to most of what was going on because I had PTSD and didn’t understand it.

“Until someone actually pointed it out to me, which was her basically, and she got me some help, we started to move forward.

“...I was lost in my head. I was suicidal; I was all those things. She hung onto me.”

Anzac Day, Mr Dobell said, was about “getting together with your mates and just showing support to each other”.

“I’m mixing with some of the best blokes you’ve ever known.”

Marg Dobell said the pair used to drive from Ballarat to Melbourne every two weeks for counselling, but local services had improved more recently.

“We didn’t know anything about post-traumatic stress, nothing,” she said.

“We probably didn’t really know it was anything to do with Vietnam.”

“Until we realised that the illness that he had was eventually diagnosed as PTSD, we understood where to go then, but it was still a hell of an up and down ride.

“It probably broke a lot of marriages. Somewhere along the line, we stuck together.”

Greg Chapman, Ballarat

Greg Chapman joined the army when he was 30 years old in 1996.

He was then sent to East Timor for six months.

“There were a few contacts,” he said.

“That was the only time people died, when I was over there.

“...I just couldn’t put the uniform on no more, once I came back.”

Mr Chapman said he broke down mentally, which affected his relationships at home.

For a time he managed a piggery, but became a frequent drinker.

“Looking back now ,the military trains you up to be aggressive, moreso as an infantry soldier,” he said.

“It’s when you get back you can’t switch it off. You come back full of enthusiasm but then once that wears off and your start to pull back into a routine, the aggression comes out.”

But he sought help in 2006, and gets a lot out of regularly catching up with other veterans at the Ballarat East Community Men’s shed.

Looking back on his service, Mr Chapman felt that overall he had done something positive for the world.

On Anzac Day, Mr Chapman attends the local dawn service, but avoids large crowds, pubs, and alcohol.

“It’s just for me and my heart,” he said.

“And just to realise that there are a lot of people who have lost their lives over the years.

“Just to think about what they did go through.”