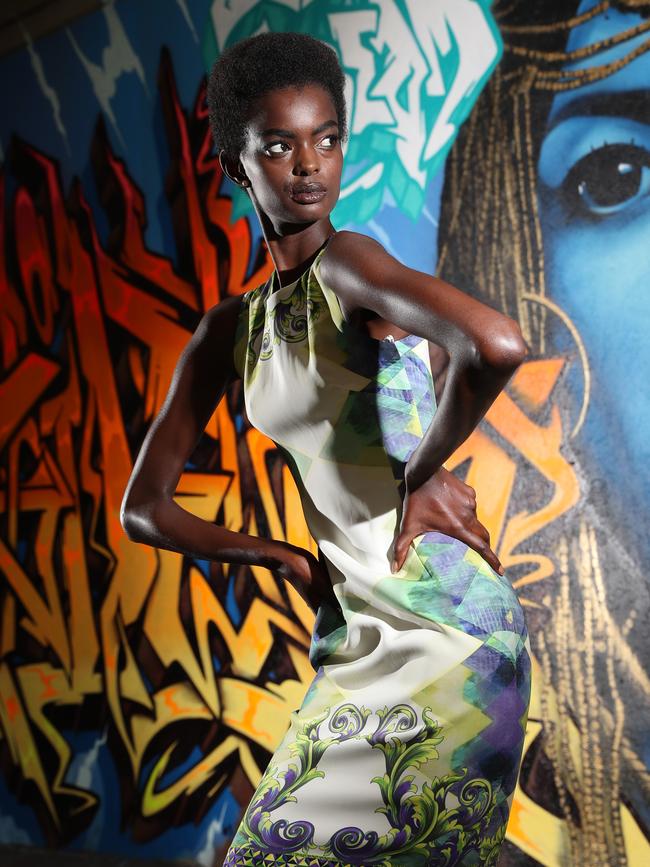

Adau Mornyang: Inside the Melbourne model’s turbulent journey

In 2019, Melbourne model Adau Mornyang made international headlines after an ugly altercation led to her arrest on a flight to LA. But, she says, there’s more to the story than just the headlines.

Confidential

Don't miss out on the headlines from Confidential. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Adau Mornyang is home, but in her mind, she’s not yet settled.

Her place, she says, lies beyond the headlines about being the model who was arrested, charged and convicted after an ugly incident on a flight from Melbourne to LA, then jailed for an alleged breach of her US working visa.

Peace, she says, will arrive as she conquers her demons, which include moving to Australia from war-torn South Sudan at the age of 10, being estranged from her family, and being raped when she was 17.

“I don’t feel like I’m home yet because I’m a different person,” Mornyang says in an exclusive interview with Weekend.

“My biggest problem is how I came home. I was deported straight out of jail. Two cops escorted me from jail to the airport. Once we got to border control, they gave my passport back, and just left me there.

“I had no money, and I just stood there in the clothes I was arrested in.”

Mornyang, 26, speaks softly, and calmly, as tears stream gently down her face.

“I’m home, but I feel like I have an invisible tattoo on my forehead that says: ‘Criminal Who Has Been Deported.’ And I feel like people see that brand wherever I go.

“I never imagined I would go to prison, let alone in the United States. They treated me like I was less than human. Then, after being locked in a cage like an animal, you’re suddenly thrown back into society, like: ‘Go and fend for yourself!’

“It’s like: ‘Where do I even begin?’”

Mornyang’s nightmare began on January 21, 2019, nine hours into a flight from Melbourne to LA. However, scarring episodes from her traumatic life unfolded long before that.

Her family fled South Sudan in 1999, and went to Egypt, before settling in Australia in 2004. While in Grade 5 and 6 at primary school in Sydney, Mornyang taught herself to read, write and speak English.

“The kids made fun of me,” she says. “I would sit and have lunch by myself. I had no friends.”

Things changed when, as the tallest student at her high school, Mornyang became a valuable asset for the basketball team. That acceptance gave her confidence to adapt and adjust to her new home.

But at home, troubles brewed.

Mornyang left home, at age 16, over a “misunderstanding” with her mother. She recalls: “My parents are very strict with strong church values. I left home and caught a bus to Melbourne with my school backpack on.”

Soon after, she moved to Adelaide to live with a cousin, but her runaway adventure took a terrifying turn.

“I got raped,” she says, by two men. “I couldn’t reach out to my own family because I had left them.”

She got therapy and has taken medication for anxiety and depression. Mornyang says she also attempted suicide.

“It took me a while to accept that I didn’t ask for it, and what they did was a crime. They were the ones who should be ashamed, not me,” she says. “Mentally, it scarred me.”

She posted an account of her rape on Facebook Live in 2017, and many women with similar experiences messaged her back, sharing their pain.

Mornyang moved back to Melbourne where the statuesque beauty, who is 188cm tall, was talented-spotted by a modelling agency. A week later, she was on a plane to South Africa to shoot a fashion campaign.

“I needed an escape, and that escape became modelling,” she says. “I did not look back after that, travelling from country to country.”

Today, Mornyang is a former global “face” for Sephora, a New York Fashion Week veteran, competed as a Miss World Australia finalist, and starred on countless runways, magazine covers and spreads for top fashion houses.

On January 21 last year, Mornyang boarded a United Airlines flight from Melbourne to Los Angeles. She went to work in the US on a 01 visa, which was due to expire on December 26, 2021.

Mornyang said she was “exhausted” when she took her seat on the plane, after working seven days and nights in a row.

She took an antidepressant, Prozac, and pain medication, Oxycodone, before take off.

During the flight, she was served two glasses of wine after one was spilt during turbulence.

“I drank two wines, I watched a movie,” she says. “The guy (seated) on my left was scared I was going to spill more wine on him. I requested a seat move, and they put me in between two girls.

“I slept for eight hours,” Mornyang says. “That’s all I remember from that episode.”

When she woke, still five hours from LA, Mornyang was arrested by air marshals.

“They put me in handcuffs without telling me why I was being arrested. My anxiety kicked in and I was hyperventilating,” she says.

“I was so confused. What happened? What did I do? From what I heard in court, I kept blacking out. I was in and out, my mouth was foaming. I was in a frightful panic.”

In court, prosecutors said Mornyang was “yelling obscenities and racial slurs and flailing her arms” after drinking wine on the flight.

They said her fellow passengers complained to the crew, and she slapped a flight attendant during attempts to calm her. Prosecutors said several air marshals had to come out from undercover to deal with her.

Mornyang, in an audio recording played to the court, told one flight attendant: “I am disturbing everybody else because of (bleep) you, you (beep) white trash b----!”

She says: “I was painted in court as a top model who was used to the high life and getting what she wants. If she doesn’t get what she wants, she lashes out. But I don’t lash out and I’m not violent. There was no intention to disturb other passengers, and I am genuinely sorry for the trouble that I caused.

“The entire episode was shameful. I am ashamed. My family has been shamed. My community has been shamed, along with everyone associated with me. And that shame was amplified by misleading media coverage.

“The air marshals knew what they were doing, though. They didn’t care about my mental state. They used it against me, and painted me as a bad person. It was as if I deserved to be locked up because of my history.”

Mornyang says after being arrested, she was taken to the back of the aircraft and held, under guard, by flight attendants and air marshals.

When she asked to use the toilet, she says two marshals followed her, and one jammed his foot against the door so it wouldn’t shut.

“I told them, ‘I need some privacy. Where am I going in handcuffs?’ They refused. So I’m sitting there, in the bathroom, trying to ignore these men staring at me with my underwear down,” Mornyang said.

“The bathroom was a safe haven, so I took my time there, and tried to gather my senses. But one of the officers got frustrated and said I was taking too long.

“He got angry and dragged me off the toilet seat with my pants down. He pinned me down, with his knee on my back. I couldn’t breathe. The more I pleaded with him, the more pressure he applied on my back.”

“When I felt his hand touch my private parts, I screamed, ‘I don’t consent! I don’t consent!’

Mornyang takes a deep breath, and softly cries. “When he pinned me down, and touched me inappropriately, that triggered me. It triggered my rape.”

Mornyang said one marshal carried her by the legs, another by her arms, with her underwear still around her ankles.

“I was exposed in front of them, in front of everyone,” she says.

“I turned to the female flight attendants, and I’m like, ‘Can you please help? I don’t want them touching me. I don’t consent.’

“And they just stared at me with looks of disapproval.”

At this point, she became verbally abusive, which was captured on tape, and later used in court by prosecutors.

“I started crying and cussing every one of them out,” she says. “I was in emotional distress. I was so angry because nobody stepped in to say the force they used was not right. They had no sympathy. They just smiled, giggled and joked.”

In March, after being held in prisons in Santa Ana and LA, Mornyang was convicted of felony interference with a flight crew and misdemeanour assault. She was acquitted of a third count of assaulting an air marshal.

US District Judge Cormac J. Carney sentenced her to three years of probation and 100 hours of community service.

Prosecutors had sought jail time.

But Carney believed Mornyang was truly sorry, citing her tearful statement to the court, that she’s receiving treatment for anxiety and depression sparked by childhood trauma, instead of self-medicating like she did at the time of the flight.

“The trial process was punishment in itself,” Carney said in court, telling Mornyang: “I want you to have a wonderful life. I hope I never see you again.”

After the trial, Mornyang returned to New York to resume her life.

However, in September, while reporting to her parole officer, she was arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers, who claimed Mornyang had been working in the US illegally.

“They handcuffed my arms and ankles to my waist, and escorted me to a van and took me away,” Mornyang said.

She was taken to Bergen County Jail, in New Jersey, and locked up with other women pleading their cases to stay in the US.

Eventually, Mornyang was told her working visa had been revoked.

“ICE don’t treat you like a human because you’re an illegal alien. You don’t have any rights in their country. Anything you say is viewed with suspicion, as an excuse,” she says.

“Just to get a single toilet tissue, or a sanitary pad, is really hard. You beg, and the more you ask them, the more the officers get angry at you, and that’s not good, because they report on you, and that affects your case.

“I tried my best to keep out of trouble. So many times I wanted to run into the wall to make it stop. But the other inmates would say, ‘Adau, if you do that, they’re going to lock you up in the psychiatric ward, and that’s worse.’”

But she said the women, 24 of them locked in a small unit, were protective of her.

“I was the youngest. A lot of them were mothers. They tried their best to help me out. Prison is not something I would wish on anyone, unless they’re rapists, paedophiles or murderers. That’s who belongs in jail.”

She says there were lots of showdowns and stabbings in jail, adding: “It was scary because I don’t know how to fight.”

However, inmate empathy turned to envy when a prison guard found a picture of Mornyang modelling in Elle Magazine and hung it on a wall for all to see.

“She showed it to all the officers. The inmates thought I was getting special treatment because the officers stated calling me ‘The Model’. But they were making a mockery of me,” Mornyang says. “To see that photo everyday was a reminder of how much I f---ed up.”

Mornyang said prison life was cold and repetitive, a dull cycle of meals, cleaning and, depending on good behaviour, access to TV and phone calls. Inmates were not allowed to exercise outdoors during winter.

“You are basically stuck there with your thoughts,” she says. “At night, when you’re lying in bed, all you hear are other girls crying because that’s all you can do. It felt like every day, it was somebody else crying. You just took turns.”

One bleak moment, amid taunts from ICE she would be deported to Sudan instead of Australia, Mornyang contemplated suicide. “I felt really lonely and abandoned,” she says. “I felt stuck and believed I was never getting out.”

But thoughts of home changed her mind.

“I didn’t want to cause more pain to my family,” she says. “I had to be strong, and I wanted my story to be heard. I wanted my freedom back, to get a taste of fresh air again.

On December 21, 2019, without notice, Mornyang was released from Bergen County Jail, taken to the airport and deported back to Australia.

She believes growing media interest in the story and behind-the-scenes assistance from Australian Foreign Affairs and Trade officials helped expedite her release.

“In prison, it’s the simple things you miss the most. The sunshine, the sky. I thought, when my day comes, I’m going to appreciate everything because I took it all for granted.”

She smiles, then laughs: “I was craving fresh fruit salad, too. In my mind, the picture of freedom was having a bowl of fruit salad in the sun.”

With flawless make up, and dressed in a designer coat, Mornyang says: “I want to move forward. “I want to close this chapter and move on. You have to be willing to accept your mistakes, acknowledge them, and change your ways.

“I want to work again, and I hope my work expresses courage and strength, and inspires others to know that just because you make a mistake, it doesn’t mean that your life is doomed.”

She is now signed to the Duval Agency in Brunswick.

“They have good connections with community, high-end fashion, and all things in between,” Mornyang says. “I look forward to working with them.”

She wants to make amends with her family, reunite with her biological mother in Sudan, finish her studies, and run modelling classes for young women like herself; “kids who had it rough, who felt like nobody was in their corner, who felt alone. I can help them avoid some pitfalls, and build their self-esteem”.

Mornyang adds: “It would be a way to give back to the community.

“Having an opportunity to set the record straight, as far as I am able, is a step in the right direction.

Asked if she will always feel, to borrow her invisible tattoo analogy, like she’s branded as “that model,” Mornyang sighs, and replies: “That’s not me.

“I’m caring, I’m loving, and I’m generous. The Adau portrayed in the media as a spoiled drunk was way off the mark. Having wrestled with her demons head on, she lashed out, at the wrong time, in the wrong place.

“I am someone’s daughter, someone’s sister. I am a human being who hasn’t had an easy life, but I’m learning each day to become a better person.”

She smiles: “My life, to date, has definitely been a journey. I’m looking forward to settling down and finding a home.”

MORE NEWS

WHY VIRUS-RIDDLED ASPEN JETSETTERS COULD ‘SAVE’ MELBOURNE