What to brace for as Australia’s favourite biscuit maker Arnott’s changes hands

Jobs axed. Brands ditched. Production shifted overseas. Is this what awaits Australia’s famous biscuit maker? Arnott’s is at the crossroads — and barrelling towards a shake-up that will send shockwaves through the nation, writes Peter Taylor.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

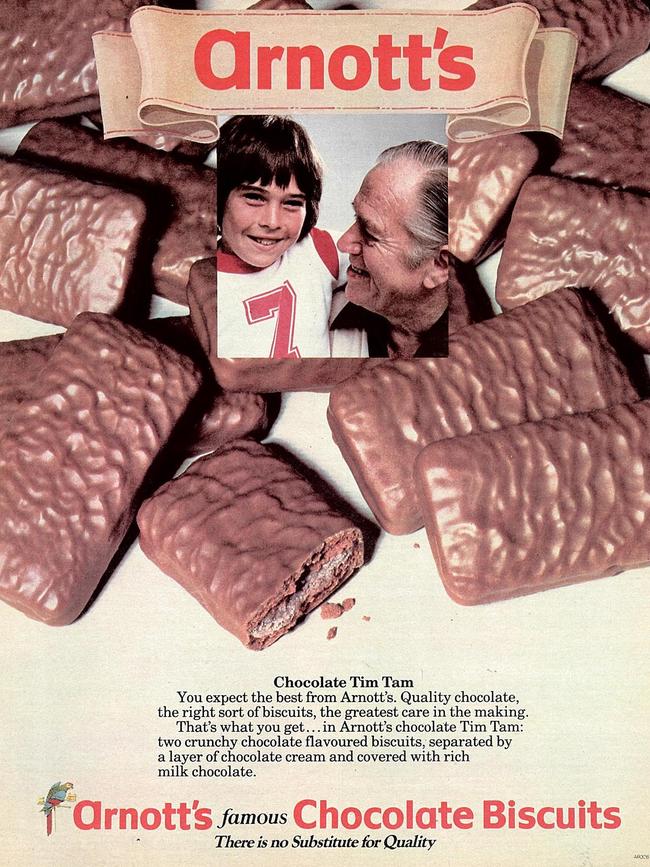

Imagine this. Tim Tam packets shrunk from 11 biscuits to eight.

Savoy axed in favour of Jatz.

Milk Arrowroot consigned to the scrap heap. And all the state varieties of Ginger Nut replaced with one national recipe.

It sounds like biscuit Armageddon, right? You bet.

But worse, imagine this. Australia’s famous biscuit company forced to shutter its factories because they are no longer viable, shifting production offshore.

Well hold on tight. The winds of change are howling at Arnott’s.

The only constant

Arnott’s, of course, is the biscuit maker behind a veritable rock-star list of Australian pantry staples — everything from Tim Tam to Salada, Shapes and Monte Carlo.

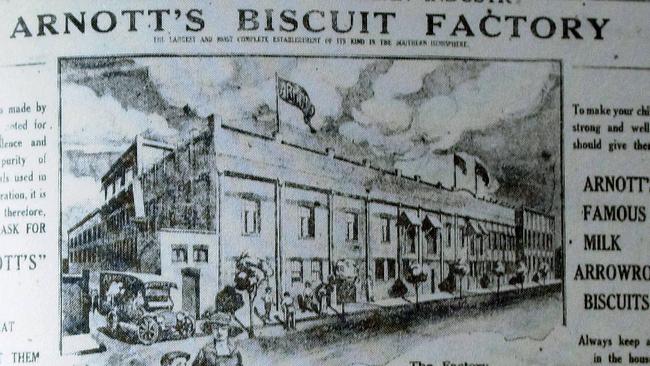

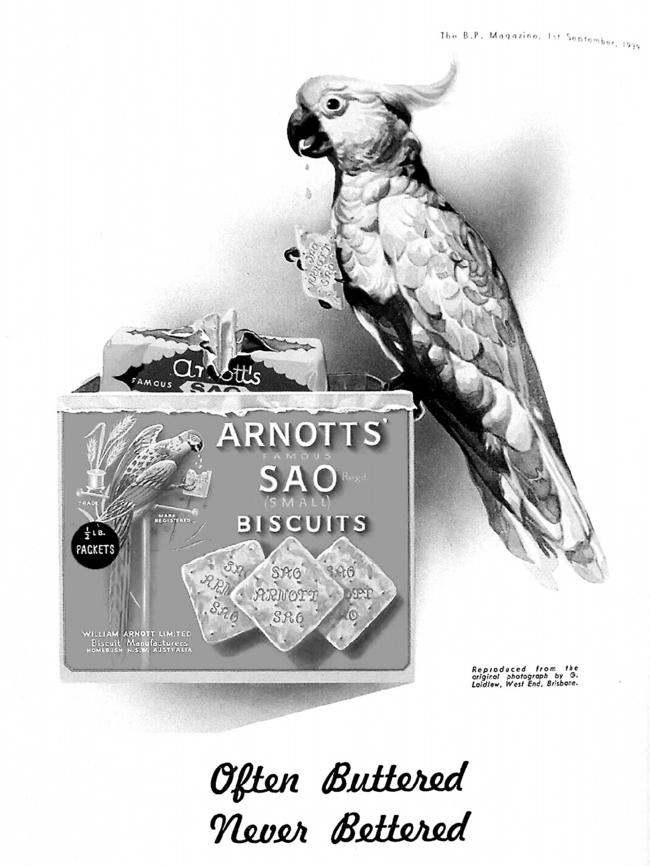

It was founded in 1865 when Scottish migrant William Arnott opened a bakery in Newcastle. Arguably, the company should trace its history back further, to 1854.

That’s when the first Australian biscuit company, Swallow & Ariell, opened in Port Melbourne. Swallow went on to produce our take on the timeless British classic, the Marie.

It was one of the many Aussie biscuit producers (others included Brockhoff Biscuits, also from Melbourne, Adelaide’s Motteram, Brisbane-based Morrow, and Perth’s Mills and Ware) who joined forces with Arnott’s mid last century.

Together, they became the Australian Biscuit Company. It was eventually rebadged as Arnott’s, which had led the consolidation drive.

While that may sound like historical trivia, it provides context about the unusual dynamics still at play in Arnott’s big book of brands.

And it also provides some clues about changes we should brace for when new owners take the reins.

New owners, you say?

If you rarely turn to the finance pages, you may have missed this: Australia’s most famous biscuit maker is being auctioned off.

Once a family-owned company and then listed on the stock exchange, Arnott’s was bought out by US titan Campbell Soup Company in 1997.

Broadly, it has since been a worthy guardian for Arnott’s.

But in its home market, Campbell’s has bitten off more than it can chew. It is now selling assets to cut debt.

Investment bankers have been working with the company to hawk the biscuit brand to potential buyers. And plenty have crunched the numbers.

A private problem

In itself, a sale of Arnott’s is no cause for concern.

In the right hands, needless to say, it could continue to prosper.

US group Mondelez, the owner of Cadbury, and Italy’s Ferrero (Tim Tams filled with Nutella, anyone?) were among those who kicked the tyres.

As it stands though, the two frontrunners are private equity houses, Australia’s Pacific Equity Partners, or PEP, and New York-based Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, or KKR.

For the uninitiated, private equity loosely refers to investment companies that buy businesses and restructure them — away from the searing glare of the stock market — with the aim of selling out a few years later at a rude profit.

If you believe the industry’s pitch, they are masters at picking companies running inefficiently, or that are ripe for bumper growth with a healthy injection of well-allocated money.

If, on the other hand, you’re of a cynical persuasion, you might interpret it this way: Private equity picks off companies it can get on the cheap, juices them (often flogging off their best assets), tarts them up and then sells them to unsuspecting buyers easily dazzled by a bit of bling.

Sweet or savoury?

In Australia, private equity has a mixed record.

Famously, electronics chain Dick Smith crashed and burned soon after it was floated — at a remarkable profit — by private equity.

Myer has struggled for much of the decade since it was floated by private equity, also at a breathtaking profit.

That said, it would be unreasonable to tar all private equity companies with the same brush.

For what it’s worth, Pacific Equity Partners — one of the frontrunners for Arnott’s — owned another famous Aussie food brand earlier this decade.

It held Peters Ice Cream for less than two years, but invested in product innovation, and among tweaks did away with the Heaven brand in favour of Connoisseur.

Peters — at least from the outside of the ice cream cabinet, looking in — appears to be in good health five years later.

In 2016, the same private equity house bought Patties Foods, owner of Four’N Twenty and Nanna’s.

So far, we’ve seen nothing to suggest it will leave that business any the poorer.

Of course, if anyone from Patties knows otherwise, get in touch … we’re all ears.

A minefield made of biscuit

Here’s the thing about Arnott’s: its greatest asset is also its greatest liability.

Over more than 150 years, it has built a remarkable war chest of goodwill and become a national champion of the biscuit industry.

Its brands are woven into the fabric of our lives. They fill the bickie jars in our pantries. They’re the playlunches in our school bags. They’re divvied out with cheese cubes at our barbies and our dinner parties.

They’ve long since become commodities in their own right, used as building blocks for homemade goodies (as Marie is to hedgehog, Lattice is to vanilla slice and Chocolate Ripple is to, well, cake).

Yet Arnott’s has not become a mainstay by accident.

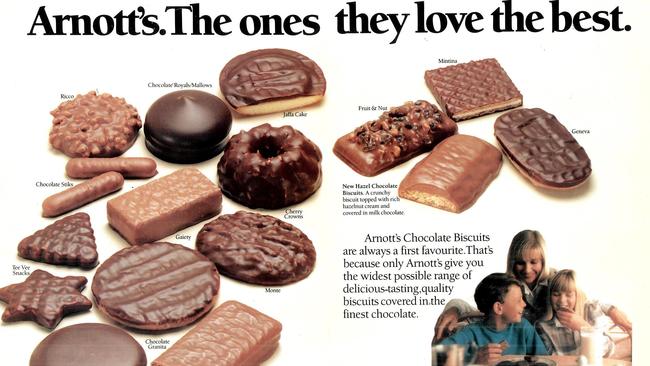

With a ravenous appetite for growth, it has picked up an enviable list of brands through acquisition: everything from Brockhoff’s Salada, Savoy and Chocolate Teddy Bear to George Weston’s Wagon Wheels.

The size of that list and the affection Australians have for those brands put Arnott’s and its parrot-adorned logo in rare air among Australian food makers.

But here’s the rub. It makes change exceedingly difficult.

An avalanche of rage awaits the Arnott’s executive who dares tinker with the tried and trusted. The company has learnt that from experience.

Rage against the machine

When it closed the ageing Brockhoff factory in Melbourne last decade, Arnott’s encountered problems trying to replicate the Salada baking process interstate.

It was inundated with calls from customers irate at what they believed was a change in recipe.

It’s worth noting the company still makes four different types of Ginger Nut biscuits, broadly along state lines, because we’re all wedded to the style we’ve grown up with.

It’s also worth noting that more than 50 years after it acquired Savoy, Arnott’s has opted not to scrap that brand or Jatz, despite their similarities.

The company has noted consumers in Victoria and New South Wales — where those biscuits respectively originated — are equally passionate about the brands and their subtle differences.

It dare not risk a backlash by changing them. When it comes to biscuits, consistency is rule number one.

Innovate or perish

So just what would a private equity company do with Arnott’s?

It could invest heavily in innovation, launching new products.

But Arnott’s already has been, and continues to be, exceptionally innovative.

If you’ve paid attention over the past 20 years, you would have noticed Arnott’s brands popping up in all manner of permutations — not just an explosion in the number of Tim Tam varieties.

Ice creams ‘inspired by’ everything from Mint Slice and Iced VoVo to Wagon Wheels. Scotch Finger infused with fruit flavours. Biscuit-themed cakes. Biscuit-themed chocolate blocks. Biscuit-themed milk drinks. ‘Cracker chips’. Packets of ‘bite-sized’ biscuits.

Many of them have come and gone. But all are examples of a company innovating with gusto.

The cost conundrum

So what else could a private equity company do differently to wring more value out of Arnott’s?

It could reduce costs, perhaps through job cuts, and perhaps by introducing new technology. But that would suggest Campbell’s has been running the business inefficiently.

From the outer, we can’t know one way or another.

But note Arnott’s did close its Melbourne plant in 2002, cut about 150 jobs in Sydney in 2008, cut almost 200 jobs in Brisbane early this decade and cut about 120 jobs in Adelaide in 2014.

That hardly points to a company resting on its laurels.

It could follow the abysmal tweaking trend among modern food makers, constantly changing (shrinking) package sizes to reduce costs, giving themselves a short-term competitive edge.

A pack of 11 original Tim Tam biscuits becomes (like the newfangled blends) a pack of eight or nine, for instance.

It could, heaven forbid, streamline its brands to make packaging, distribution, marketing and sourcing ingredients more cost effective.

By our count, Arnott’s makes more than 110 varieties of biscuits and crackers. That points, perhaps, to an unwieldy product portfolio ripe for consolidation.

Out goes Jatz or Savoy. Out go four different types of Ginger Nut, ushering in a One Ginger Nut Nation.

Perhaps the axe falls on either Milk Arrowroot or Milk Coffee, and on Granita or Shredded Wheatmeal … and the list goes on.

But you can only imagine the outrage from Pearl on the Peninsula and all her friends at the croquet club — not to mention the rest of Australia. Change at your peril.

Property of Australia

There is something else a short-term owner could do at Arnott’s. And it almost certainly will.

Rumour has it the buyer will move quickly to strike “sale and leaseback” deals at Arnott’s three factories, in Sydney, Brisbane and Adelaide.

That is, it will sell those factories, then (necessarily, of course) sign Arnott’s to long-term leases at each site.

The private equity company scores a bumper payday from what is essentially a big property play. It then makes a few cosmetic tweaks to the brand, sells up and moves on.

It’s elegant. It’s simple. It’s modern-day business (who actually owns their own properties nowadays, after all?).

And Arnott’s is left forever paying rent for the factories that make Australia’s favourite biscuits.

That should concern all of us.

READ MORE:

Up go Arnott’s costs. Down goes its asset base. In years to come, when lease terms are renewed, landlords have the company over a barrel.

And the corporate biscuit-jar raiders have long since galloped off into the sunset.

Suddenly, consolidation becomes not an option, but a necessity. It becomes a necessity to cut costs. It becomes a necessity to streamline products.

It becomes a necessity to turn the screws on ingredient suppliers, and ultimately to close plants and send manufacturing offshore. And we all cop the crunch.

So here’s a little a memo to the private equity companies circling the Australian biscuit company.

Sure, it has been owned by America for the past 22 years. And it might soon be owned by you.

But know this: Arnott’s is the property of Australia. And if you want to buy in then cut and run, well that doesn’t just take the biscuit.

That’s exploiting and endangering an Aussie icon built up over more than 150 years. And Australia won’t take it lying down.