Australia’s migration levels remain well above pre-pandemic figures

Australia’s net migration remains high, as both sides of politics gear up for a fight on the issue.

Business Breaking News

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business Breaking News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Australia’s net migration will likely come into focus during the upcoming federal election, as the number of arrivals remains above pre-pandemic levels.

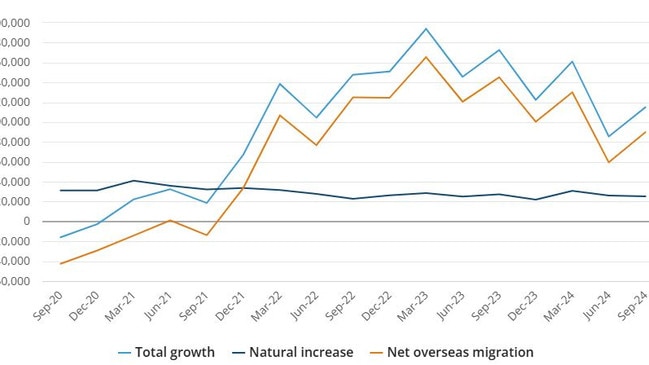

Australia’s population grew by 484,000 or 1.8 per cent in the 12 months before September 30, Australian Bureau of Statistics data shows.

There were 617,900 people arriving from overseas and 238,100 departing, meaning 379,800 people were added to our population from overseas migration, which is down on recent quarters.

Meanwhile, natural births minus deaths added 104,200 people.

The latest population data comes as both sides of politics argue for migration to be capped.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said his party was committed to decreasing net migration from the peak of 510,000 in 2022-23 to 250,000 by June 2025, aligning with pre-pandemic figures.

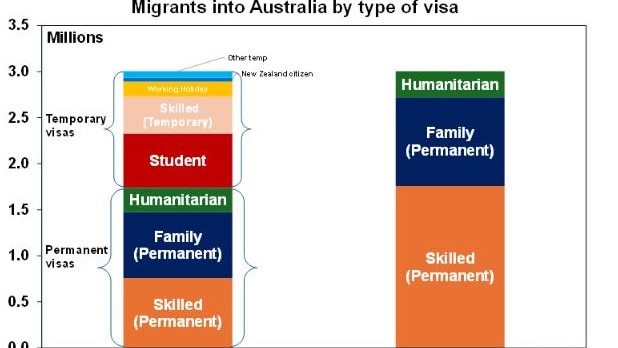

Opposition Leader Peter Dutton said he wanted to cut permanent migration by 25 per cent over two years from 185,000 down to 140,000, although the Coalition is yet to announce its net immigration target.

Mr Dutton has also said he would implement stricter international student caps below Labor’s proposed 30,500 a year, although he has not announced the figure.

Economic benefit

Grattan Institute deputy program director economic policy Trent Wiltshire said as Australians argued about migration, it was benefiting the economy.

“Overall the skilled migration program provides a large economic benefit to Australia and that benefit primarily occurs through fiscal dividends we get from young skilled migrants earning good money and paying taxes,” he said.

Mr Wiltshire also said migration could also help boost Australia’s productivity, which remains behind target.

“Australia’s productivity has been very poor recently and is around where it was almost a decade ago. So really it’s been a lost decade, with productivity the key way to improve our living standards over the long run,” he said.

“There has been research out of the OECD over the past couple of years that showed skilled migration can boost productivity growth.

“We can do skilled migration on top of a whole bunch of other policies as well. We should be aiming to improve our university and TAFE, encouraging business to train staff and bring in skilled migrants.”

AMP economist My Bui said immigration had boosted GDP without negatively impacting the labour market, as it added to both the demand and supply of labour.

“In the long run, Australia will benefit from adjusting the composition of the migrant population by implementing policies that address genuine skill shortages, reduce concentration in capital cities and lower the pressures of an ageing population,” she said.

Mr Wiltshire agreed and highlighted that skilled migration didn’t push down local wages.

“Often, the skills that come in, or the skill workers that come in, are complementary to the workers here. And if we boost productivity, that creates jobs in new industries as well,” he said.

Housing challenge

While both Ms Bui and Mr Wiltshire said migration had long-term benefits, Australia does have a housing shortage.

Ms Bui said newly arrived migrants were often younger and looked to settle in places with low unemployment, meaning they primarily move to Sydney and Melbourne.

“Consequently, the recent wave of immigrants might not have adequately addressed the skill shortage problems in regional areas,” she Bui said.

“Compounding this issue is the fact that immigrants are less likely to work in construction compared to the Australian-born population, with only 2.8 per cent of migrants who arrived in the last five years employed in construction, adding to the construction labour shortage.”

Ms Bui said, in part, migration helped push new dwellings inflation higher, but the key driver of housing remained a mismatch between housing demand and supply.

Mr Wiltshire said one of the challenges for Australia’s migration program was a lack of housing to keep up with demand, adding about 1 per cent to rental prices per 100,000 new arrivals.

“We don’t think migration has been the main driver of Australia’s housing crisis, but it has been a factor,” he said.

“We have seen a fast run of migration that has pushed up rents, but that doesn’t mean we should pull back or completely destroy our migration policy.

“We should build more housing so it’s cheaper for everyone.”

Originally published as Australia’s migration levels remain well above pre-pandemic figures