Inside the secret world of the NSW Undercover Branch

For the first time the unheralded senior operatives from NSW Police’s most cloistered unit — the Undercover Branch — reveal their secrets. From catching the Lin family murderer to spending seven months infiltrating a paedophile ring — these are their incredible stories. EXCLUSIVE AUDIO

Josh Harris does a very good impression of a hitman. His ex-colleague Rob makes a great drug dealer, and Mark’s impersonation of an addict is flawless. All have pretended to be — and befriended — paedophiles. They have coaxed confessions from killers, swapped cash for cocaine, and become best pals with embittered civilians who want someone killed.

They are shapeshifters, great pretenders, actors with a gift for playing all kinds of sinners.

“Do you want them in the hospital or the cemetery?” became one agent’s signature line, delivered dead-eyed and cold and just above a whisper, so his hidden microphone would pick it up.

Many undercovers even look like hitmen, if that helps conjure an image — but that is all that can be said about physicality, because these officers’ true identity and any descriptions of them remain court-ordered secrets.

Each morning, they get out of bed and put on a mask. They call themselves “Jeff” or “George” or “Rick”. They might live in Balmain and Parramatta or Randwick. They are married and they are single. They carry three or four phones. They are the state’s finest crime-solving assets, unicorns in the world of law enforcement — full-time operatives with the NSW Undercover Branch.

To hear any operative speak is rare but the undercovers who are interviewed for this story have an incredible set of adventures to recount. One brought down the Lin family murderer, Robert Xie, by eliciting damning admissions about one of the worst mass homicides in NSW history.

Another recorded Charlotte Lindstrom, a beguiling Swedish model, asking him to execute two Crown witnesses.

A third gleaned a vital tip off that led to the arrest of 1980s serial killer Lindsey Robert Rose, a former ambulance officer who quit to work as a private eye, then descended into violent robberies and murder.

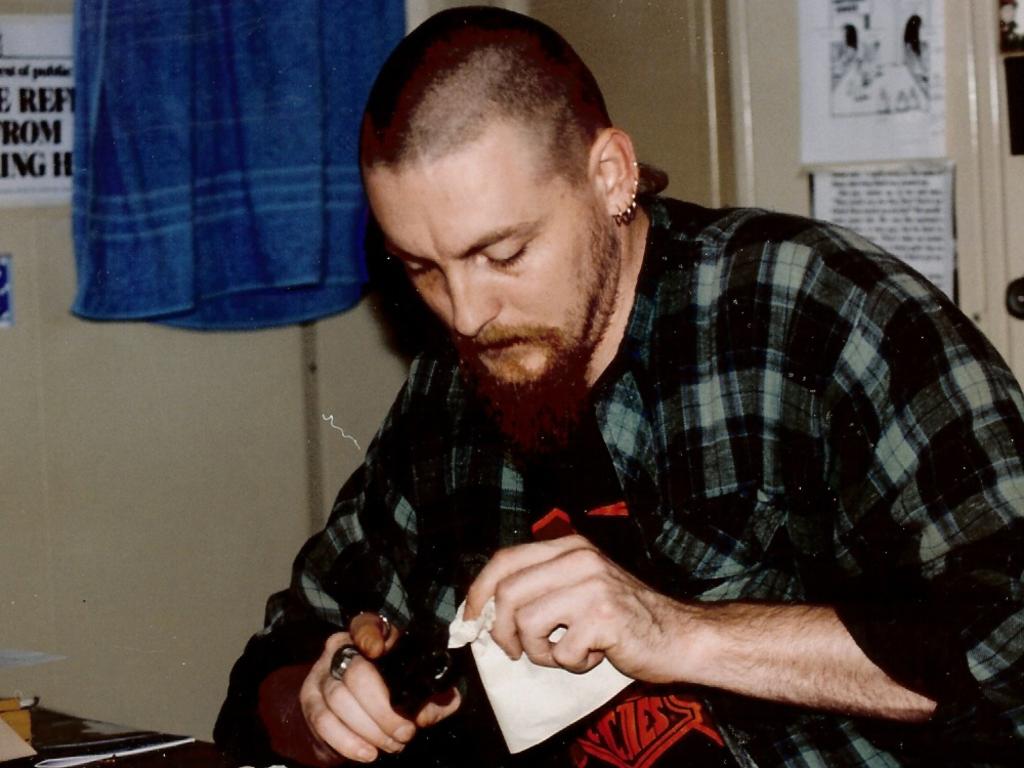

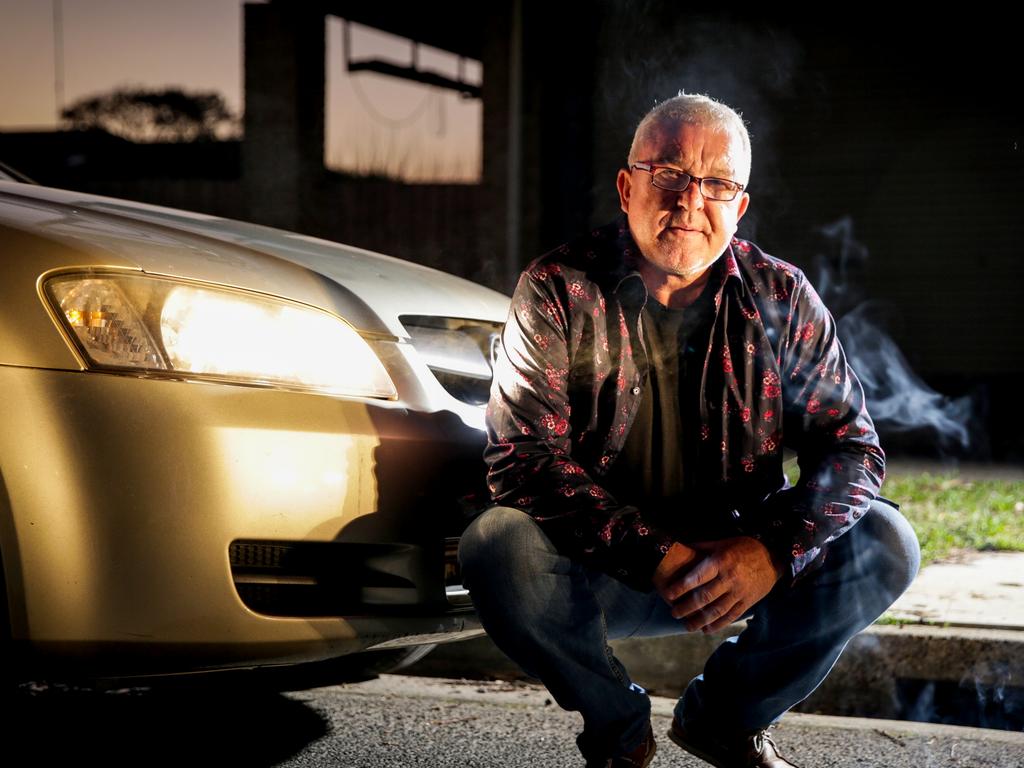

Three of the former undercovers interviewed for this investigation chose to speak on the record and gave permission for the use of their real names: Andrew Curran, Andy MacFarlane and Michael Drury, perhaps the most famous undercover cop in NSW history.

These are stories that have never been told before, and some police would have preferred it to stay that way, because the Undercover Branch prides itself on absolute secrecy — not just to the public but within the police force itself. Even to serving cops this unit is mysterious and misunderstood, as foreign as ASIO and just as invisible.

When operatives do step out of the shadows, perhaps on the day of a bust, or in a closed court giving evidence, they appear wraithlike to the average cop; protected and cloistered, surrounded by minders.

“People get caught up in how important you are,” a former operative said. “You’re on a pedestal,” said another.

One undercover, Adam, spent seven months infiltrating a network of paedophiles across NSW, from Sydney to Port Macquarie to Coonabarabran to a sad, rundown caravan park in the regional city of Orange. To do this, he had to all but become a paedophile. He had to absorb the terrible images and memorise the names of each child, the “collections” to which they belonged. He had to study the videos — watch them over and over — so he could dissect them with his targets and pretend he loved every second.

“It was a true test of craft,” Adam said, showing me a Commissioner’s Unit Citation he received for his role, which has never been publicised. The Citation is the highest accolade available to a NSW police officer.

“It was a good test of my undercover skills because I went in cold. I had nothing to offer them — no money, no drugs.”

Because of this work and because Australia’s criminal population is so concentrated, no undercover feels even remotely at ease when they step outside their front door. There is only a slight risk he or she will run into someone they’ve fooled, but it does happen. Once, while buying clothes in a shopping centre, Josh bumped into a woman who, months earlier, had asked him to rob the business where she used to work.

Another time, at an airport carpark, Rob locked eyes with a man who had just been released from prison. They recognised each other immediately — Rob had met the man numerous times at an inner city cafe, bought obscene amounts of cocaine from him, and assured him repeatedly that he wasn’t a cop.

Inherently dangerous and life-threatening at times, it’s somewhat contradictory this daring, exacting career path remains attractive to people.

A 1986 study of 82 serving and non-serving undercover officers working for the Honolulu Police Department found the job steeply increased feelings of guilt, anxiety, loneliness, and put pressure on marriages.

There has been little scientific examination of the profession since, especially in NSW, where operatives undergo mandatory psychological assessments and are restricted to fixed terms, after which they have to return to mainstream policing, an enormous anticlimax and struggle in itself.

One of the only Australian studies into undercover policing — a 2003 PhD dissertation by Dr Nicole French, a psychologist who surveyed operatives nationwide — found this transition period often seals the deal on an operative’s career, leaving them deflated, unappreciated, and stigmatised by their uniformed colleagues, many of whom, due to the secrecy, have no idea what the work involves.

“Regular police think you are drug f**ked,” an operative told the study. A second said, “They think we are nothing but drug smoking hippies.”

A third remarked, “I thought about leaving but I have no other skills.”

This “reintegration” process — the return to rosters and logbooks and a uniform — is the inevitable comedown off the wild ride of deep-cover work, a career that offers zero public glory or recognition and, for all its hardships, pays roughly the same salary as that of a beat cop, a junior detective, or a shelf-stacker at Woolworths.

Put simply, there are safer ways to make a living, and yet there is never a shortage of applicants wanting to step through its hidden doorway.

“It’s a great feeling when you pull a big job,” said Andy MacFarlane, a decorated operative who spent nine years working undercover.

“It’s the thrill of the chase. The great unknown,” he said.

“It was one of those units that people lathered up to try get to, because they were fascinated by it, but not always willing to step through the looking glass.”

One undercover, Rob, can attest to this. He wore many hats while working undercover but donned many others before joining the cops. He was a barista, a gardener, a driver for an electrician’s business and a childcare worker before finally enlisting to become a police officer. In the early 2000s he graduated from the academy and was posted to Western Sydney, then a hotbed of Middle Eastern criminal activity, his first year whirling by in a torrent of mundane traffic accidents, domestic disputes and point duty. He considered quitting but his boss talked him into a transfer to a plainclothes unit.

One day, some colleagues asked him to manage surveillance on a small-time dealer selling $20 “sticks” of pot from a house in Riverwood. Through a camera lens, Rob watched as “pool undercovers” — fully trained agents who work part-time — bluffed their way inside and walked out with little bags of evidence. He was awed. “It was exciting,” he said. “It was sexy. I thought, ‘That’s what I want to be doing’.”

NSW Police Commissioner Mick Fuller did not participate in this story, apart from offering this comment: “The NSW Police Undercover Branch is right up there with the best in the world and I am incredibly proud of the work they do. Only recently I met with very senior police from across Europe who were out here to see how we do it. I was an undercover supervisor myself back in the late ’90s so I have a great understanding of the craft and absolute admiration for these officers.”

TRAINING DAY

A point so obvious that it’s almost not worth mentioning is you need to be a good liar if you want to be an undercover cop. There are, of course, many other prerequisites, like resilience and grit and life experience and nous and an ability to read people. But underpinning it all is the ability to spin a yarn, to extricate oneself from a jam if necessary — and it will become necessary, the training itself makes this clear. Exercises are designed to mess with recruits’ heads. They’re recorded and played back to highlight a lack of ease with a drug deal, or bad eye contact, or the slightest hesitation at a tough question.

People have frozen up under the pressure of this grilling, or crumpled into tears when asked about their drug history, which isn’t necessarily frowned upon in this area of policing. Operatives are marked down if they’re too stiff, too straight.

This selection panel is just the final stage of the gauntlet. First, there’s a live-in course, a psychometric assessment, a medical, and hours and hours of role-playing scenarios where recruits are tested on how well they deflect a line of cocaine, or the allegation that they’re actually a cop.

The Sunday Telegraph pieced together a general picture of this training through civil court documents, methods used overseas, and interviews with former operatives, supervisors, trainers, and other police officials who agreed to speak on-the-record and anonymously.

It all starts with a one-week Street Level Operatives course where students are taught the basics of buying drugs. Some of these cops have never used a bong before, or seen an ice pipe. They have to memorise the slang dictionary, learn the difference between an “8-ball” and an ounce, and are given a rundown on prices so they don’t overpay for a gram of coke.

They discover that their first assignments, at the bottom levels of the drug world, will probably be “cold”, meaning they’ll arrive on the dealer’s doorstep without the benefit of an introduction.

Later, they can apply for the live-in training course. Held at a covert location, the trainees develop longer-term cover identities and undergo testing for up to 18 hours a day.

“They increase the pressure of each scenario and teach techniques along the way,” a former operative said.

Instructors playing drug dealers will attempt to pat down the trainees, move the ‘deal’ to a less secure location, or throw random curve ball questions to push recruits off balance (“Why was there a vacant lot at the address listed on your driver’s licence?”)

Passing these tests elevates the trainee from a Street-Level Operative to a ‘Pool Undercover’, a part-time position which involves more distinguished targets: mid-level dealers and syndicate bosses, guys who call themselves ‘businessmen’ but don’t touch the drugs they sell.

Some will drive a Camry and dress like they need the money, but the less savvy will don the usual gangster finery — a hefty gold chain, a chunky necklace.

But this work and these targets are still dangerous. Police rarely die in the line of duty but when it happens the circumstances tend to be surprisingly routine — a vehicle stop, a neighbourhood dispute, an unforeseen danger lurking within the banality of day-to-day drudge work. Pool undercovers, therefore, never really know what they’re walking into when they’re deployed to a house, or told to meet someone in a carpark. They won’t know if their target is high, or paranoid, or armed with a weapon and setting an ambush.

“If the crook thinks you’re an easy target, you can get knocked over and even killed,” said Michael Drury, a renowned former operative who went on to write the training manual for undercover policing in Australia.

“Occupationally, you are very isolated. You have to meet some of the most undesirable people in our community and tell them you’re their friend, let’s do crime together — sell drugs, child pornography, whatever the case may be. They’re not nice people, morally speaking, and it does have an emotional impact.”

Reaching the Undercover Branch provides slightly more certainty, but only because the targets have been analysed and surveilled ahead of time by the detectives asking for help. At the Branch the jobs also go wider than drug work.

There are ‘hitman’ jobs, ‘decoy’ jobs, ‘paedophile’ jobs and ‘cell’ jobs. There are also ‘homicide’ jobs, where the goal is to elicit a full confession from the target, someone whose secret is buried in a bush grave, or at the bottom of a mine shaft — a secret they were hoping would die along with them.

SECRET BRANCH HEADQUARTERS

Somewhere in NSW is a shopfront registered to a fictitious company. It’s hidden within a smattering of light industry: smash repairers, furniture retailers, video stores, financial firms. Walk through its doorway and you will find the covert office of the NSW Undercover Branch, a venue so secretive that there are no cleaners to wipe the windows or empty the fridge in the kitchenette. In this tightly controlled environment the operatives vacuum the carpets and take turns mopping the floors; they also shred their own documents and must act normal if anyone walks in off the street. Few police know its location — even the Commissioner doesn’t know where to find it.

The NSW Police Force declined to participate in this story when I first approached them in 2018, but revised their position (somewhat grudgingly) when the size and scope of the piece became apparent. After some discussion, I was connected with the commander of the NSW Undercover Branch. For the purpose of this piece I’ll him ‘Henry’.

There are no photographs of Henry available on the Internet, which is why I walked straight past him on the day we met at a city cafe. He has been in charge for the last eight years and, like his operatives, works under an assumed identity.

These are his first public comments about undercover work.

“It’s important that operatives never lose their real identity, so the Branch is a psychological sanctuary as well as a physical sanctuary,” he said, likening the office to a safe-zone, one of the few places where staff can loosen their collars and use their true names without fear of exposure. Even inside a police station this isn’t possible, because cover identities must be maintained at all times.

Henry declined to say how many jobs pass his desk, or how many are accepted. “Most,” is all he would say. “I’ll often accept the job but not with the suggested direction of the investigators,” he added. Some jobs, he explained, are better suited to a female operative, or a younger operative, or to a different scenario than the one detectives had in mind. “We accept more than we turn down, but that’s a reflection of the investigators using us — they know what we can and can’t do.”

On arrival at the Branch recruits are given a new driver’s licence, birth certificate, an entry in the Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages, and even a passport if they’re likely to chase criminals overseas. Each identity requires a wallet and a phone, and some operatives carry three wallets and three phones during their time at the Branch because their workload is so high. There might be a sturdy legion of ‘pool undercovers’ working across the state, but the number of full-time operatives — those who work exclusively on complex, long-term, deep-cover missions — is not very high.

Each facade also comes with its own complicated backstory that must be remembered down to its finest detail. Not just the full name and date of birth, but also the family history, career history, car rego and everything else associated with an entire life. But for a lie to seem real it needs a skein of truth running through it, and this is why operatives practice the subtle art of ‘backstopping’. Applied in its most basic terms, it means that if an operative is pretending to live in Double Bay, they should be seen standing in line at the Sheaf as often as possible, or sipping cocktails at Pelicano, or reclining on one of the wicker chairs at Cosmopolitan. In other words, create a presence for themselves, make the lie seem real.

If this sounds like a perk there are others, too. Recruits can grow out their hair, grow a goatee, wear heels, a mini-skirt, and generally violate the police force’s dress code policy for as long as their rotation lasts — but not a minute longer. From day one, even during their training, operatives are given career counselling to reinforce that their time at the Branch is temporary. It’s to stop them from quitting, or psychologically crashing, once their rotation expires. “Before they start, they know it’s not forever,” Henry said.

YOU’RE A F***ING COP

It’s the moment every undercover cop knows is coming and there is only one way to survive: stay calm.

For Andrew Curran, the dreaded moment came in 1997 when he started buying speed from the Rebels outlaw motorcycle gang. One of their suppliers, Vince*, was a violent, mid-level dealer who kept a crew of goombahs around his safe house in Green Valley, a flop with a carport where drugs were bagged and money was counted.

The street was a cul-de-sac, which meant physical surveillance was virtually impossible.

“Any strange cars would stick out and my cover would be blown,” Curran said. A boy from the bush, he’d never used a bong before or even seen one before he joined the Undercover Branch in 1995.

He made his first buys from Vince with the help of an informant, a criminal who had been cutting deals with police but kept breaking the law. When the informant was pulled over one day driving a stolen car, he demanded the charges be dropped because of his ongoing assistance. Detectives said no, and as punishment he threatened to out Curran to the bikies — telling them Curran was a fellow informant.

“A lot of criminals who are too afraid to kill a police officer are not afraid to kill an informant,” Curran said.

To Curran’s amazement, and confusion, senior cops wanted him to keep buying speed from Vince. On the day of his next deployment he could sense the danger. Six men were sitting around a plastic table, all staring.

“The hatred emanating from them was almost a physical force,” Curran said.

The advice on panic is always counterintuitive. Swimmers are advised to stay perfectly still if they see a shark in the water. But adhering to this advice is almost impossible in the real world, which is why Curran froze, his heart pounding in his ear and his mind spiralling with snap calculations. Turn around? Run for it? Stay staunch? Keep buying?

Vince told Curran to follow him into the kitchen, which was strange because normally he carried the gear on him.

“He was patting his pockets saying, ‘Where did I f … in’ put it?’” Curran said.

Drug dealers never misplace their stash, which is why Curran watched in terror as Vince started rifling through drawers pretending to look for the drugs.

“I could see my shirt vibrating because my heart was beating so hard,” he said. “I was waiting for him to pull out a knife or a gun.”

The lucky break came when Vince spotted a car outside in the driveway with another operative sitting in the passenger seat. He grew angry at the sight of it, furious that Curran had brought an unknown person to his door. Curran passed the cop off as his buyer, someone who wanted the drugs Vince was carrying. That saved him.

“He told me to come back in 20 minutes on my own and he would have the drugs for me,” Curran said, the relief almost overwhelming as he walked out of the kitchen back to his car, his back tensed as he expected someone to launch a king-hit on him.

These cases are common. Another agent, Adam, was sent into a house in Bass Hill posing as a construction worker. He was given a patdown at the door, then thrust into a room reeking of bong smoke and chemicals. He counted 10 large Middle Eastern men through the haze, plus the dealer, a guy named Tony. One of them was squinting at him. “You’re a f..... cop,” he said. “I’ve seen you before. I’ve seen you at Lakemba.”

With each sentence the goon shoved a pool cue into Adam’s side, but he’d given himself away — Adam had never worked at Lakemba. It was a bluff.

Fortunately, Tony the dealer was blinded by the opportunity to make money, which is why he calmed his boys and pulled out a small bag of speed.

“You’re scaring me,” Adam kept saying to the bloke in his face, as he tried to negotiate, settling on a price of $100. When he pulled out his wallet the goon next to him let out a grunt. “You can pick undercover cops,” he said. “You can pick them because they always have real crisp notes.”

Adam cringed, because he’d unwittingly been given two perfectly crisp notes by his bosses. The sight of them set off the room like a barnyard.

“You’re a f.....g cop!” the men kept shouting, as he palmed the drugs and walked out of the room. Tony’s men followed him down the hallway, jabbing pool cues into his back and taunting him as he started his car.

Originally published as Inside the secret world of the NSW Undercover Branch