Inside the key moments of Shane Warne’s ‘Truman Show’ life in the spotlight

Shane Warne once said his life was like a version of the Truman Show. We watched his biggest, best and toughest moments play out before our eyes.

Cricket

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cricket. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Shane Warne woke at 5am, rolled over to light the first dart of the morning, and checked the hundreds of new texts and emails. He felt jittery about the day ahead.

After a charity breakfast, Warne got to the MCG dressing room early.

He sparked up a quiet smoke in his corner, to ponder both his retirement and the prospect of taking his 700th Test wicket in front of his family in his home town.

On the MCG field, for the final time in a Test, Warne blocked out the life distractions. Cricket, for Warne, was always the ultimate distraction.

As if he walked on to the ground and a door shut behind him.

It wasn’t his first ball or first over.

But when Warne bowled England’s Andrew Strauss, he had never heard a bigger roar on a cricket field.

He started running with joy so that his teammates had to catch up.

Almost 90,000 fans would chant Warne’s name when he walked off that day.

Warne felt that everyone in Australia wanted him to take that wicket.

“Looking back I’ve often thought my life has been a bit like the Truman Show – after all, I turned from boy into man on people’s televisions …” he wrote in his book, No Spin, in 2018.

“And I like to entertain,” he said.

“Perhaps it’s as simple, or as complicated as that.”

Warne liked other things, too, such as loud music, smoking, drinking and bowling a “bit of leg spin”.

The sum of his conflicting parts – the generosity and sensitivity, the kindness and boorishness, the patience and impulse – will always confound the obituarises.

But his stature goes unquestioned.

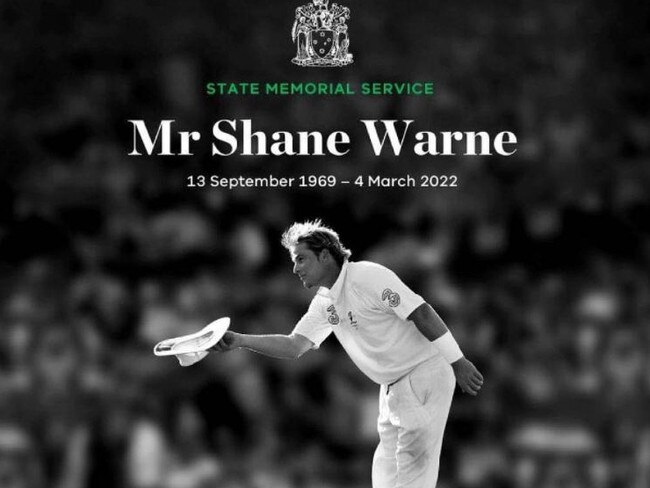

Today’s front page features an iconic image of Warne doffing his hat to an adoring crowd.

It is the image his family chose to run on the front of his home town paper, of which he was an avid reader.

The ingredients for the magic, as it would be known, may have been first tapped when Warne was three.

He broke both legs when another kid jumped on him.

Plastered from neck to knee, Warne lay flat on a trolley and scooted around the house, perhaps developing arm, shoulder and finger muscles which would explain some, but not all, of his later superstardom.

As a kid, he played footy and tennis, mostly.

Tennis seemed better than cricket.

He credited Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket for inspiring backyard cricket matches with brother Jason, later his best man, with whom he would engage in the odd blood-soaked spat.

They imitated their cricketing heroes, as so many boys did.

Warne admired the Chappell brothers and Rod Marsh the most.

Warne started bowling spin at age 11.

“It came out great and I kept doing it,” he said.

Yet footy remained his thing.

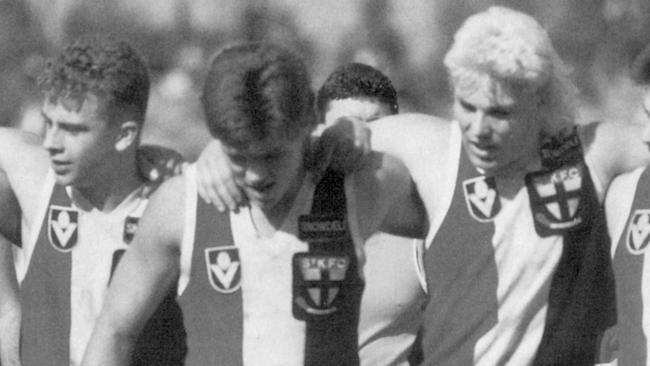

Constantly caned at school, cheeky and academically inattentive, he started playing for St Kilda under 19s in year 12, then a full season the year after, in which he finished as the club’s highest goalkicker.

He was delisted the following year. “The truth is I was never good enough – not a mile off, but in the end not good enough,” Warne later said.

He delivered pizzas and beds, uncertain of what was next, until a mate enticed him to play club cricket in England.

There, Warne learned to play, to drink, and to have fun.

He also learned to learn.

His drive to succeed, summed up in his adoption of 10,000 hours theory of practice popularised by writer Malcolm Gladwell, surprised him at the time.

On that trip, Warne left Australia at 79 kilograms and returned at 99.

“The fact is, I was a bogan,” Warne would say of his beer-swilling and larks.

“I still am deep down, really.”

He left the Australian Cricket Academy after flashing his behind at two women in a hotel pool.

He played state cricket and toured overseas.

At the Boxing Day Test of 1991, he ran into Ian McDonald, the Australian team manager, while loaded up with pies and beer.

McDonald told him to go easy because “you might be playing in Sydney (the following test)”.

Warne felt overawed, a doubt compounded by his Sydney Test first innings bowling figures of 1/150.

As someone said, Warne looked “like someone’s mate filling in until a proper player turned up”.

On a whim, Warne drove eight hours to see Terry Jenner, a former Test spinner, who told Warne at the front door that he was fat and ill-disciplined, then hosted Warne in his home for six weeks.

Warne lost weight.

He began to learn what would become his sporting trademark – the psychology and planning of taking a wicket.

The same year, at the MCG, Warne took 7/52 against the West Indies.

A strong series in New Zealand was followed by the “ball that changed my life”, his first ball of the 1993 Ashes series.

The dismissal of England’s Mike Gatting became the most sublime moment in cricket folklore.

Warne’s blonded hair and smudged zinc cream.

His dip and turn.

The immortal Warne, the bloke we would all come to think we knew, was cast.

“It was very hard to take at the time,” Warne told BBC Sport in 2018.

“You walk out of your hotel and there are 20 photographers following you … at 22 years of age I’d never experienced anything like that …

“All I tried to do was be honest, upfront, and just be me, and along the way I made plenty of mistakes … I’ve never pretended to be something I’m not and I think that’s why people still like me.”

Former Australian player Simon O’Donnell once called Warne “the smartest dumb bloke I know”.

Warne voiced original ideas about the future of cricket.

In company, he was all about good manners because his mother Brigitte “shoved (them) down our throat”.

Yet Warne made many errors, such as accepting a bookie’s bribe of $5000 for pitch conditions in 1994 (and apparently blowing it at the casino), and for being banned for 12 months for taking a banned drug, ostensibly as a diuretic to slim down.

Warne was unapologetic about his vanity – his “look good, feel good” mantra explains the whitest of teeth and the way his hair looked thicker at 50 than on the day, at 37, he took his 700th wicket.

His personal life was a resume in unashamed hijinx.

Warne kept falling into the wrong beds.

After wife Simone and the three kids arrived in London in 2005, to be confronted by stories of his philandering, they went home.

Warne wallowed by crying and getting drunk from mini bars on hotel room floors (and snagged 40 wickets in one of the premier contests of cricket history).

He said he had only two serious romantic relationships – Simone and Elizabeth Hurley. “Believe it or not, I’d take the quiet life over the red carpet any day …” he said in No Spin. “I have lived in the moment and ignored the consequences.”

Warne was a better father than husband, even if his post-career commitments filled almost every day, about half of them elsewhere in the world.

He regretted the hurt inflicted on his kids. But otherwise regrets seemed pointless.

Warne always smoked.

He took up the habit as a teenager (Peter Jackson 10-packs for 30 cents) at about the same time his father, Keith, gave up after a collapsed lung.

Warne was fond of liquid diets which can throw out the blood’s electrolyte levels and risk the heart.

He ate poorly at times.

These choices may have been factors in his sudden death at 52.

Another factor may have been overlooked in most of the obituaries.

Warne’s grandfather, Joey, was built like a tank.

A Polish refugee, he turned up in Victoria, via Germany, in 1949, worked hard, then died suddenly of a heart attack in his 50s.

More Coverage

Originally published as Inside the key moments of Shane Warne’s ‘Truman Show’ life in the spotlight