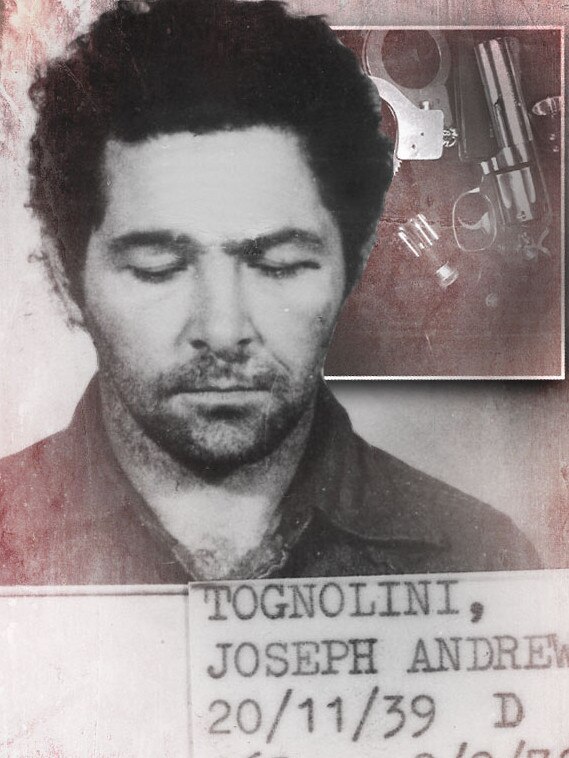

True Crime Australia: Joe Tognolini, confessions of a notorious Aussie safebreaker — Part 2

WITH his mate Fritz, Joe Tognolini sat atop Australia’s most wanted list in the 70s and 80s. Today, he recalls shootouts with cops, honour among thieves and his fifth and final breakout

True Crime

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT’S winter 1980 and the gloomy, bleak weather reflected Joe Tognolini’s apparent predicament.

In the early hours of June 28, Joe sat inside his third-floor Yatala cell with only his escalating heartbeat as a soundtrack, waiting for the prison bars to tinkle.

After four prison escapes, including one with his mate Werner “Fritz” Thrun from Mt Gambier jail in 1978, Joe was subject to the highest security SA had to offer.

It wasn’t enough.

As Joe’s anticipation rose, two mates were breaking into Yatala Labour Prison, lugging an oxyaceltaline welding kit to increase the degree of difficulty.

After scaling the prison’s imposing stone walls, the two mystery men climbed to the roof of the prison and used a rope to dangle outside Joe’s cell.

Seconds later, sparks began to fly as the intense blue flame began to soften the steel bars, with the noise sending shivers of dread up Joe’s spine.

“They cut through two major gates and then up onto the roof near where I was,” he says.

“A woman rang up from the Northfield women’s prison and said she saw sparks streaming out of a window. They didn’t act on it.

“I heard the gates banging and I thought f..k they’re doing a cell check.”

A frantic call of “block it up, block it up” from the darkness sent Joe stuffing wet toilet paper into every nook of his cell, positive the warden was on his way.

“I thought if the smoke gets out it’s all over. And then (the guard) came up to my level, the third level, but then it turned out he checked everywhere except my little wing.

“It was like it had been engineered. But it wasn’t.”

Disaster averted, the oxyaceltaline kit arced up again, and after an hour Joe carefully placed the roasting metal bars onto the cell floor and joined his mates on the second tranche of their mission impossible – getting back out.

“On the way down, directly below me was (fellow prisoner) Bruce Sandery, who was a very good friend and he actually said is there any gas left?,” Joe says.

“I said, ‘mate it’s f..ked. I’d have you with me but there’s nothing there’ and he knew that I was telling the truth and all he said was ‘good luck mate’.

“And as I went down all I could hear was ‘good luck’ and ‘see ya’ – they’d all been watching. And I thought how many bloody people could have blown the whistle on me.”

Joe has written several books on his exploits and says everything in them is based on truth. Except the Yatala escape.

“In the book I said I didn’t know they were coming, but of course I knew,” he says.

“How else would they have known where my window was three floors up? We did have a signal arrangement.”

WHEN it’s put to Joe that the men who broke him out had “balls of steel”, he pauses and looks into the distance.

After several seconds of silence , Joe replies simply: “But I would have done it for them. They were risking their life,” he says.

“Those screws (prison officers) in those days, they could shoot. Back then they had guns and violence and the okay to shoot and their jobs were on the line if they didn’t.

“So you think, yeah they could shoot me. And if a 455 hit you, you weren’t getting up. The bullets were as big as my thumbs.

“There are very few people who would do that for you.

“Most people will open their pocket for you.

“Some will throw you a rope but they won’t come up it. There’s usually a line.”

The unflinchingly brave escape led to Joe reuniting in Queensland with Fritz - who had performed his own Houdini act months earlier.

During the six months between the Yatala breakout and his eventual arrest in Far North Queensland, a number of brazen break-ins occurred in the sunshine state.

JOE was charged with five thefts from Queensland police stations, in which guns and handcuffs were stolen.

Some of those items were found, and it appeared the case against him was as safe as houses.

But Joe broke into both safes and houses, and decided to represent himself at trial.

“It was a jury trial and the jury can only say one of two things: Guilty or not guilty,” he says cheekily.

As a self-represented defendant, the law permitted Joe to delve deep into the police case against him.

It didn’t take long for him to find cracks in the case the Queensland detectives had put before the court.

With the guns, cuffs and Joe in a seemingly gift-wrapped prosecution case, the detectives forgot to tick all their boxes. Joe could hardly believe his luck.

“When you put them to proof that means they’ve got to go back and produce all the documents that preceded it but they didn’t exist,” he says.

“For example, and it sounds ridiculous, but I asked for proof the police stations were locked because technically if they weren’t you can enter them.”

Frustrated prosecutors soon twigged their “iron-clad” case was crumbling like an overcooked Anzac biscuit and entered a “nolle prosequi” – legalese for dropping the case.

His miraculous court escape did little to endear him to the constabulary across Australia.

Even today, Joe regards most uniformed police as straight, honest men and women. But he has no time for the network of “special squads”.

Sipping his third beer during our lengthy interview – a light, because he’s driving – Joe recalls the days when cops and robbers settled their differences with the odd suburban gunfight.

Prison was one risk of Joe’s former criminal career path. So was getting shot by cops.

“Once they used to send in maybe two cars and they’d use stealth and ability, that was the key to it, they had the ability,” he says.

“They’d just sneak in, put the gun to your head, hammer you to the ground and they got you.

“But then it got to the point where they said ‘we don’t want to risk all that’. So now they’ll have 37 police rock up, f..king flak jackets on to catch someone who’s threatened someone with a pocket knife.

“That’s outrageous. You could’ve had three bikies run in and got him. They’d just run in and punch him in the head and take the pocket knife off him.

“They haven’t really got it together, they just haven’t.”

JOE’S five prison breaks matched the number of times he got in the way of bullets fired with the intention of killing him.

The closest of his five shaves with death came with a hole through the cheek in a shootout with Victorian police. “I got shot in the leg, in the hand, in the mouth, in the head. Two (of those injuries were) by cops,” he says.

“I’ve had a lot of guys tell me about the bullets that missed, and the first thing I say to them is ‘well, you don’t count the ones that miss once you’ve been hit’ because you think ‘didn’t hit me, so who cares’.”

Another time, Joe was seconds from an early exit when a “rat” had a revolver to his head inside his own home.

But Joe knew a lot about guns. And the one pressed to his temple was known as a “pepper box”.

“In the old days a pepper box had multiple barrels, and when you pulled the trigger the barrel turned, if you grab the pepper box it won’t fire,” he says.

“But there were three models out of about 20 that have the striker rotate inside and the barrels don’t turn and unfortunately that’s one of the ones I grabbed.

“So as I grabbed it he was pulling the trigger and it went through here (his finger) and I was able to hang on.”

A bullet exploded from the gun, shattering Joe’s finger. But he was yet to feel any pain thanks to the adrenaline coursing through his boxer’s physique.

“I wrestled the gun off him and then I just kept punching and punching. He thought he was on a winner you see,” Joe says.

“Those people are like bullies, they’re tough until they’re on the ground.

“Then they say ‘please stop’ and you say ‘nah, nah, nah, I’m just getting my second wind here!”

The would-be assassin escaped the duel alive but never came back for another crack at Joe.

When asked if any of the hundreds of criminals he encountered had caused him fear, Joe pauses as though it is a question he’s never before pondered.

“That I feared? Nope, not at all personally, no. Well, some inside there are just f...ing idiots.

“I can actually remember one guy in there trying to slash me with a razor but he was just a f...ing idiot so I just knocked him to the ground and told him not to do it again and that was the end of it.”

ONE of the men killed in Melbourne’s gangland wars of the 1990s was safebreaking legend Graham “The Munster” Kinniburgh – a man Joe respected and staunchly refused to give up when offered his freedom by desperate detectives in the 1970s.

Joe has little time for most of the others slain in the underbelly wars, including Alphonse Gangitano, who was no more than a “f...ing w...er”

“He threatened people who couldn’t hurt him. He was violent towards people who weren’t violent. How is that tough?,” he asks shaking his head.

“Picking on someone smaller and younger than you .... you just wouldn’t do that.

“Some of the people that are more criminal than I’ve ever been, you will never hear about.”

Lots of crims are tough on the street, but “you can’t measure someone until they’re caught”, Joe says.

“If a citizen gives you up and you get caught that’s fair enough, you’ve f...ed up badly and the police have capitalised on it, that wouldn’t bother me at all.

“But if it’s someone you trusted, some f...ing rat that you’ve invited into your own home, you know. It’s quite different.”

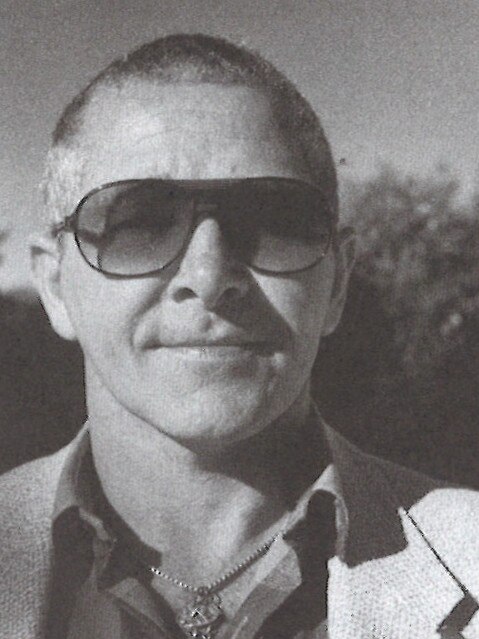

JOE eventually served another four years in Yatala then returned to Victoria to finish his debt to society.

In 1988, he found himself in the real world for the first time in most of his adult life.

He was upfront about his criminal past and that was not attractive to most prospective employers.

But then a job came up as caretaker of a man-made island off Port Phillip Bay, built in the 1800s as a fort to keep watch for the Russians who never invaded.

Ironically his experience in solitary confinement and the belief of a woman on the hiring panel saw Joe fixing the derelict fort and becoming a tour guide for fascinated visitors.

Later he got work in the Victorian environment department and then moved to South Australia’s Fleurieu Peninsula just over a year ago.

Three decades of the “real world” have not dampened Joe’s opinions on what he sees as injustice against some elements of the criminal world, such as bikies.

“With bikies it’s because they’re out there and easy to spot, so they are an easy and popular target,” he says.

“It’s a bit like the drugs, they catch the ones who are smoking it or selling it on the street, not the ones higher up the chain.”

He has a problem with crimes against the establishment incurring harsher punishment than crimes against innocent citizens.

“All my life I’ve seen it, they come down hardest on those who basically are a threat to the system or the police,” he says.

“Guys were getting eight, 10 or 12 years for armed robbery, and some other idiot comes in and has frightened some granny half to death, and they get six months.

“If someone stole my car I’m not gonna be happy about it, but if someone hits one of my sisters, I’m definitely not gonna be happy about it.”

He regards his crimes as honourable and insists he never hurt an innocent member of the general public.

“Back then we were going up against professional people, I’m not talking about the poor bank teller, but the armoured guards and that are paid to do that,” he says.

“And the moment (lawmakers) can’t stop something all they do is make the punishment greater.

“It doesn’t work, it doesn’t scare anybody, all it does is frighten off those who can be frightened.”

He says it is the same in prisons.

“They love blaming visitors like some poor old woman for bringing drugs in and they dress them up like bloody monkeys.

“When I was there it was the bloody screws bringing them in,” he says.

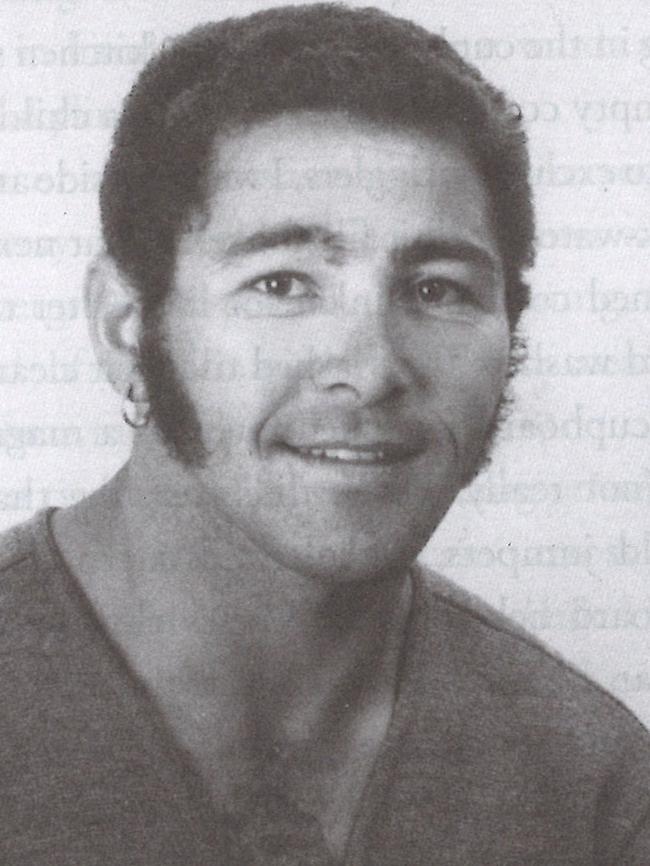

Despite his greying hair and advancing years, Joe’s nuggety physique and 50-year old sleeve tattoos belie his deeply philosophical views on life.

One of those beliefs aligns with the Chinese theory that there is no such thing as a crisis – only opportunity.

“When you’re in a hole it’s f...ed. I remember being in solitary and thinking ‘I’m f...ed here’,” he says.

“Then I said to myself, no wait a minute, I can develop my memory in here, and you know you’ve turned it into a positive.”

In Monday’s Advertiser, Joe Tognolini reveals his thoughts on prisons, rehabilitation, and why Don Dunstan was a man ahead of his time.

Originally published as True Crime Australia: Joe Tognolini, confessions of a notorious Aussie safebreaker — Part 2