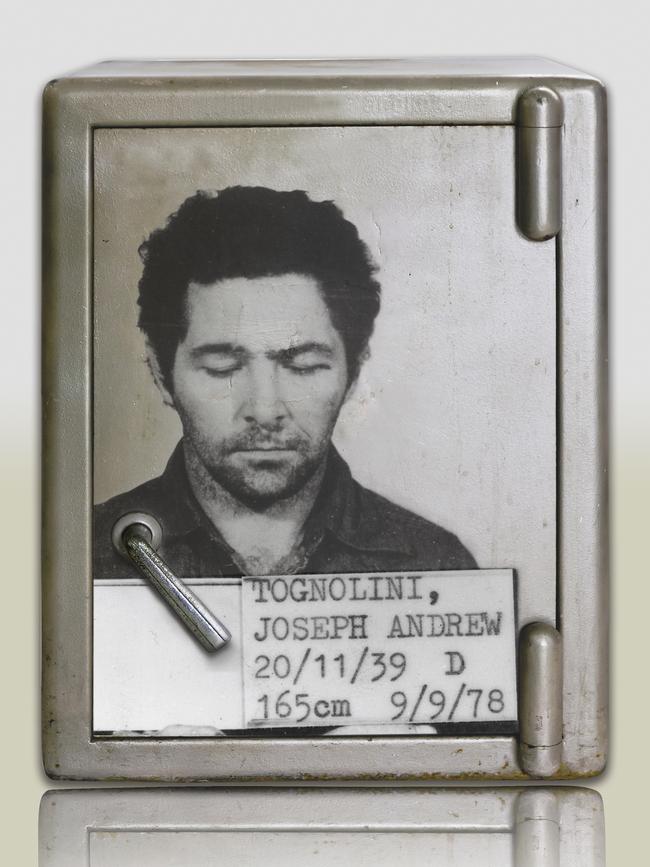

True Crime Australia: Joe Tognolini, confessions of a notorious Aussie safebreaker - Part 1

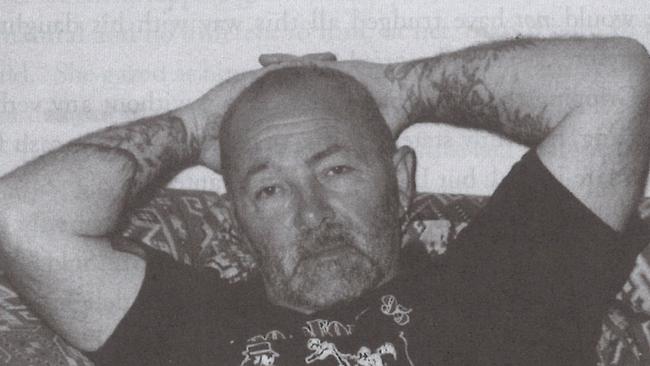

He did time with the last man hanged in Australia, was locked up with Chopper Read and escaped from prison as many times as he was shot - and he was shot a lot. Now in his 70s, former notorious safebreaker Joe Tognolini is now enjoying a seaside retirement south of Adelaide, where The Advertiser tracked him down.

He did time with the last man hanged in Australia, was locked up with Chopper Read and escaped from prison as many times as he was shot - and he was shot a lot. Now in his 70s and retired from crime and traditional work, Joe Tognolini is now enjoying a seaside retirement south of Adelaide, where The Advertiser tracked him down.

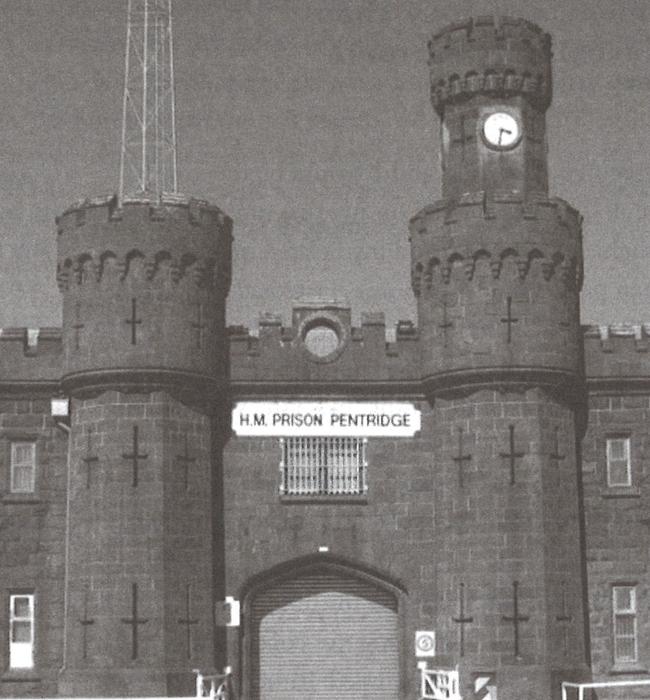

Joseph Andrew Tognolini was deemed incorrigible within the Draconian juvenile justice system of the 1960s, so was sent to Melbourne’s Pentridge Prison with the big boys.

But if the plan was to scare the wayward teen straight, it failed.

Joe’s belligerence continued, winning him the respect of older inmates and a place in the notorious B Division of the now-closed prison.

“B Division was the only division that had all the criminals who killed criminals. They were not allowed to be with the others,” he explains. “They were the dangerous ones, because they didn’t fear any person. So in B Division there were no rapists, because they were no f***ing good, they’d inform on you under pressure so they were out.”

Now basking in the afternoon spring sun outside his local hotel south of Adelaide, Joe recalls serving time when the call “dead man walking” still rang out through the cold walls of Pentridge.

“The first time I heard them yelling “dead man walking” I sat up and thought I was going to see a dead body on a stretcher. Then this bloke would walk through. They were the ones condemned to death,” he says.

Joe recalls the warders greasing up the trapdoors in preparation for the execution of Ronald Ryan, the last man to die by state sanction in Australian history.

Career crook Ryan was condemned to death by hanging after being convicted of the shooting murder of Pentridge warder George Hodson in 1965, but had spent time breaking into safes. Safebreaking was considered the elite of the criminal world, and that is where young Joe wanted to sit. So one afternoon he ambled up to the gruff Ryan.

“I met Ryan once ... a couple of the places he’d robbed had involved very old safes so at the time I thought ‘oh, he knows about safes’,” he says.

“So I approached him and I asked him could he give me some (advice). And he said ‘you ever tried working son?' And I went ‘oh f*** off’, I walked away totally disappointed. And that’s all I remember of him,” Joe laughs.

February 3, 1967. Hanging Day

The smile evaporates from Joe’s face when asked if he recalls the morning of February 3, 1965, when Ronald Ryan hung from a noose until he was dead.

“It was very weird, the week before. But on the day that he hung we were all locked up, of course, because they were worried there might be an incident,” he says.

“Prison is never silent, there’s always f***ing noise, clanging and banging and yelling - it’s never, ever quiet, even in the middle of the night.

“But that day there was total silence. It was quite eerie. When the time came, the whole place just went dead silent.”

Nobody was meant to fraternise with the dead men walking. But young Joe thought they might just be the blokes with the best advice.

“You couldn’t go near them, it was a penalty if you went near them but I used to go straight in, I didn’t give a f*** and I used to play chess with a bloke who became one of my best mates,” Joe says.

“He was meant to hang, he was in the condemned yard and when I was ducking in there I think there was five in there.

“But none of them ever got hung, they all got commuted.”

There was a strictly-obeyed code of silence within B Division. The penalty for lagging was similar to Ronald Ryan’s - but quicker and bloodier. During a four-year stint B Division, Tognolini witnessed “three bombs, four murders, easily 20 stabbings".

“I was in B Division when there was one particular murder, and everyone just scattered, that’s how it worked,” he says. “When the head of security came in, he stopped a little guy called Keith, and (the guard) said ‘stand still’ so Keith went bang and broke his nose and Keith was off.

“I know that wouldn’t happen in prison now. Most would stop because they don’t have a camaraderie or system in place.”

There is “zero comparison” between those days and now, he says.

Chopper Read

“Chopper” is an entertaining myth, at risk of becoming “fact”, Joe says of former Pentridge inmate, the late Mark Brandon Read.

“Read was down in H Division on protection, but he turns it all around the other way to say that he was dangerous to all the rest,” he says.

“But seriously – that man wouldn’t have made it through the passage of B Division, he’d have been hammered to the ground.”

Joe echoes many in the know who say Read’s wildly-successful novels and the award-winning film Chopper were no more than a Frankenstein’s monster of other men’s deeds stitched together with himself as the marauding villain.

“I think it was his last book and he actually told a lot truths about himself and I thought that was a good one,” Joe says. “But his other ones, there were crimes in there that were other people’s crimes, because I knew the people that did them. They weren’t his at all, none of them. Zero.”

In fact, Read was what is known inside as “a dog”, according to Joe.

“He was working for the police, they gave him a bulletproof vest and put a wire on him to try and get information, he worked for them,” he says.

“But I’m not against him, so long as he was not anywhere near me.

“He’s a guy who very cleverly packaged the whole thing together. People accepted it and it’ll become true soon.”

Joe also laughs about the antics of Chopper’s best mate Jimmy Loughnan, who in the film stabbed Read to near-death.

Loughnan was among a group of inmates who burned to death in the 1987 Jika Jika fire they started. Another unable to rebut Chopper Read’s “fantasies”.

“Poor old Jimmy. He was a lost cause, he used to put his overcoat on and stuff it with newspapers in case he got stabbed,” Joe laughs.

Safebreaking, and the ‘pub gang’

Even among the assortment of ratbags and scumbags who formed the tapestry of the 1970s crime fraternity, Tognolini was one of a kind. He was famous among crims and even quietly admired by some cops for his prowess for safebreaking.

Also for alleged large-scale thievery and frequent but unscheduled absences from Her Majesty’s budget hotels across Australia.Joe says he didn’t waste time on soft targets and focused his skills on robbing the people who had the big cash.... and those “who had it” inside were often crooked ex-police officers, many of whom ran country pubs. Pubs with safes. Safes that often had lots of cash and illegal guns.

He scowls while explaining why crooked cops were the perfect mark. “They should be in prison, they’ve got no right to be out there, some of the dirty deeds they did,” he says. Did targeting crooked police come with extra risks? “Yeah. But if you get the jump on them, who cares who they are? Who gives a s***!,” he laughs raucously.

“That’s why I liked it, because they couldn’t report it. They’d bleat and cry and carry on but there was nothing they could do. So, it was good. I must acknowledge that.

“But at the same time you would’ve got worse prison time than the average break-in guy, because safes were in a category of their own, it proved that you were determined.

“Armed robberies, you’ve only got to be running on your nerves three, four, minutes, at the most maybe 10 minutes,” he says.

“But a safe, you might be in there two days, or you might be in there five days, one day each week until you get there in the end.”

Not many did it, or knew what was required. Also the equipment was not cheap.

“Once I spent five-grand just to buy the equipment and an expendable vehicle before I even got started.

“Most people would’ve been happy just get the $5000, whereas that $5000 investment got me $68,000 in the end, and that’s about quarter-of-a-million now,” he says.

“But the money wasn’t it. If you haven’t go the determination, I seen some f***ing terrible things happen in prison that probably can’t happen now.”

In late 1978, South Australian police swooped on Joe and his then-girlfriend in the carpark of a northern suburbs shopping centre.

He was arrested and charged with being a member of an infamous group dubbed the “Pub Gang”, which had stolen $115,000 in 65 different breaks of hotels mostly in SA’s upper and lower southeast.

Man of letters

Tognolini was an articulate writer whose handwritten letters found their way onto the pages of The Advertiser.

After he and his longstanding partner-in-crime, Werner Thrun, escaped from the crumbling walls of Mount Gambier Prison on November 29, 1978, Tognolini felt that a stern but polite letter was in order.

Already in possession of a reputation as a staunch and loyal crim within such circles, Tognolini was miffed by the slightly different version proffered by police - of an “extremely dangerous” thief who would shoot his way out of trouble.

Tognolini and Thrun were arrested.

But anyone who has ever set foot in the now-closed old Mount Gambier Gaol would not be shocked that two of Australia’s most adept escape artists could manage to break free of the almost “no-security” institution.

Now a backpackers hostel and entertainment venue, the gaol and its inmates were separated from Reidy Park Primary School and its pupils by a wire fence.

The fence was topped with barbed wire as a deterrent, however prisoners wandering off for a day or two before coming back of their own accord was about as common as small children who would snake their way under the jail fence to retrieve an errant football.

Despite the prison’s security relying pretty much on the same trusting nature of an office chocolate fundraiser, the only incident this former Reidy Park pupil recalls was the Potato War of 1982, as it was forever branded in my mind if nobody else’s.

As they toiled in the large garden, one prisoner reacted to the childish gibe “hahaha sucked in you are in jail” by throwing a spud over the fence.

It sparked a brief but arguably hilarious “spud war”, an absolute riot of fun for the army of junior primary kids and the prisoners – but strangely the mirth and sense of occasion escaped the female teacher who sprinted into the fray screaming for an end to proceedings.

In hindsight, that teacher was probably the responsible one. She was probably the only one on either side of the jail fence who wasn’t already in on the joke that us kids could get in if we wanted and the guys in green jumpers could probably get out if they could be bothered as well.

So it was surprising that Tognolini and Thrun were held on remand on serious charges in a prison incapable of keeping children OUT of the grounds when authorities knew both were professional crooks, leagues worse than the fine dodgers and minor offenders around them.

It was eminently less surprising when the pair were noticed missing, the crooks not even sticking around long enough to throw a single spud at the schoolkids.

It was not the most elaborate prison break and for professional safecrackers it must have been as difficult as tying shoelaces.

Country tunes

THE limestone walls of the old gaol were soft and penetrable enough that the pair of crooks carved a hole through the wall with a kitchen knife.

And that was the hard bit.

A climb through a ceiling, then a quick scamper over the stone prison walls using a tennis net as a makeshift ladder, and the pair were off across the school oval, just before the sun rose and well before any pesky schoolkids began arriving to potentially foil their getaway.

In fairness to the prison bosses, they had installed an electronic alarm on the perimeter of the jail days earlier, after had correctly guessed neither Tognolini or Thrun were planning a lengthy stay in the Mount.

But in another stroke of luck for the inmates, the “hi-tech” alarm system proved useless.

A series of false alarms caused by an “electrical defect” led to the early-shift guard ignoring another in a series of warnings about 5am.

As luck would have it, that warning proved the security did work sometimes, and the Corrections Department’s acting director tried hard to vouch for the guard in what he kindly called “a chapter of accidents”.

“He (the guard) probably thought the electronic field was just malfunctioning again when he

couldn’t see anything going on. We believe that is when they escaped,” acting director Mr W. A. Stewart told The Advertiser.

With the startling observation that “the whole affair seems to have been planned from inside”, Mr Stewart conceded that the pair of high-security rated inmates had been given a free kick or two from the outset.

Planning was assisted when Tognolini and Thrun were placed in a cell with each other, but the “remand section of the jail was crowded”.

Furthermore, neither man should have been detained in the minimum-security Mt Gambier jail.

But in keeping with the comparatively blasé attitude, the pair was gifted two months planning time before making their dash.

The department blamed the courts for its failure to move the high-profile inmates to another more secure facility. The courts had been too slow in coming to a ruling whether the pair face should face trial over the theft spree in Mt Gambier or Adelaide.

While the country prison’s security was never compared to Alcatraz, the escape led to at least one crackdown by jail bosses. Prisoners were no longer permitted to keep kitchen utensils inside their cells.

But kids kept getting back in every time a footy flew over the fence, prisoners kept throwing wayward balls back to the schoolkids and still nobody noticed or cared. The two important prisoners were gone and not likely to return.

Crooks, cops and the news media had an interesting dynamic in the ‘70s and ‘80s which seemed to be tinged with at least some degree of mutual respect from all corners.

As the heavily-tattooed Tognolini displayed in his 1978 letter while at large, many underworld figures or accused offenders saw the media as an avenue to tell their side of events, while police and “old school” crims often shared a begrudging respect and occasional strange quasi-friendships.

Thrun’s freedom run lasted 10 days before police nabbed him near Adelaide.

Tognolini remained at large but he was far from happy with the police and the way he had been portrayed by them and the media.

He concluded the best way “to set a few facts straight” was a letter to The Advertiser.

“I am not a member of some Pub Gang of some notoriety,” he wrote.

A jury would later disagree.

But Tognolini probably saw that coming and almost certainly knew that no matter what happened, he would break out again anyway.

Tognolini’s public pledge to peacefully hand himself in came on the condition police allow him his legal right to silence and treat him with respect and nonviolence.

Accusing two detectives of concocting false allegations against him and Thrun and querying the disappearance of $10,500 cash seized when police raided his caravan and arrested him, Tognolini’s forthright letter outlined his alleged mistreatment.

“I sat virtually silent for three days, was assaulted, menaced, falsely charged and had a false record of interview conducted,” Tognolini wrote.

“What I vigorously contest is my alleged admission of those crimes … and the wilful and malicious concocting of evidence by those two officers to further their own ends, whatever they might be.”

Accusations he assaulted two plainclothes police were an “utter falsity” as were the contents of his purported confession but he freely admitted hurling a typewriter in frustration.

Tognolini told the newspaper the heavy-handed treatment of police, and a charge that he tried to escape from the interview – two months before he and Thrun actually did escape – were trumped up by officers nervous about the injuries they inflicted upon him in an effort to force him to confess.

“I was punched and kicked into submission – and did not fight back nor speak. The escape charge is to account for my wounds and any complaint I might utter,” he wrote.

“So being falsely charged, I set out to obtain my freedom to allow me to bring my case before some jurisdiction of enquiry.

“I am not armed nor do I intend to be in the future. It is not my intent to resist apprehension with force, I will surrender peacefully.”

Tognolini’s eloquent prose mimicked the legal parlance he spent much of his life tuning in to from the dock.

The career crim’s use of language and clearly outlined peace offer displayed a classy twist to his cheeky demands, and was more sophisticated than the 21st century version of wanted crims.

Almost 40 years on, many Australians have never handwritten a letter, or probably ever received one, and Facebook pictures featuring men with facial tattoos, flicking the middle finger at the camera is the modern version of Joe Togg’s letter.

In contrast to the brazen and elaborate escape the pair would years later pull off to free Tognolini from Yatala, the pair probably felt like footballers who received a downfield kick for goal from the square.

Prisoners who had escaped were stripped of privileges for each attempt, and after managing to escape five times, Joe’s incarceration in Yatala was inside the high-security section.

“By the time of your fifth one, it’s almost impossible to escape, you’ve got to pull a rabbit out of the hat. Which I did,” he says with a flickering smile.

Originally published as True Crime Australia: Joe Tognolini, confessions of a notorious Aussie safebreaker - Part 1