How NSW Police use facial recognition tech to track down suspects

Facial recognition technology has been marred in controversy in the United States but in Sydney, police claim it is playing a key role in identifying suspects in serious and organised crime — and there are plans to expand even further.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When killer Mert Ney went on a warpath through Sydney‘s CBD, killing one woman and stabbing another, police urgently needed to retrace his steps.

The covert Facial Recognition and Biometric Unit used a close up image of Ney’s bumbag and his face to track his movements through the city across hours of seized CCTV and phone footage.

The technology stitched together a timeline of the murderer’s movements not only in the city but on the public transport network.

“We used his face and that identified him, maybe 90 per cent of the time,” State Intelligence commander Assistant Commissioner Tony Crandell said.

“He actually had a pretty distinctive bumbag so we said ‘why don’t we just identify the object and track that’.

“The bumbag was picked up 100 per cent of the time.”

In what would have taken a team of four detectives four months, took the Facial Recognition and Biometric Unit three days.

Facial recognition technology and artificial intelligence is the latest forensic frontier for law enforcement.

It helps investigators identify a person of interest by using algorithms to compare the facial geometry of someone captured in CCTV footage or a still image against mugshots on a police database.

But the technology has attracted it’s fair share of controversy, which might explain why policing agencies have been reluctant to talk openly about it.

For the first time this week, NSW Police opened the doors to their Facial Recognition Unit.

“I want to just be as transparent as possible and say, yes, people are not going to agree with this,” Mr Crandell said.

“But we have privacy in mind too.”

Police have been using PhotoTrac, which stores one million photographs of people arrested and charged in NSW, to compare against potential suspects caught on CCTV, for at least the past decade.

But there are plans to build on that technology significantly.

NSW Police is in talks with Roads and Maritime Services (RMS) about accessing vehicle data that could help identify cars used in crimes where a registration wasn’t recorded.

Under the proposal, police would could request data the RMS about based on the make and model of a car and then narrow down the search using specifics, like bull bars or spoilers. That would create a short list for police to investigate.

“I’m only talking about serious and organised crime here,” Mr Crandell said.

“Really you probably wouldn’t put that into a shoplifter.”

Mr Crandell said police also worked with a private, real-time intelligence company that helps retail stores, including Woolworths and Shell service stations identify and flag banned shoppers.

Investigators can run those images against PhotoTrac or use them to investigate organised crime theft networks, like baby formula rackets.

NSW Police trialled live facial technology at a gun show in a bid to identify anyone banned from holding a firearm but the accuracy wasn’t up to scratch.

From a social acceptance standpoint, Mr Crandell doesn’t think NSW is ready for that yet either.

“Personally I don‘t think the benefits are worth it at this point,” he said.

“That might change depending on what society‘s view is.”

Any police reach into the public sphere, where people expect to carry out their lives with a degree of autonomy, is a hard sell.

However, if it‘s to identify serious criminals, like suspected terrorists or murderers, and done under the guidance of the Privacy Commissioner, Mr Crandell believes he can get the community on-board.

FACIAL RECOGNITION UNIT

At the Curtis Cheng Centre, NSW Police’s headquarters in Parramatta, 10 police officers make up the FRU.

The unit was formed three years ago in anticipation of a national biometrics database – dubbed The Capability – that was meant to allow law enforcement to mine driver’s licence and passport photo records from around the country to identify suspects.

But the bill to regulate the technology was kiboshed by a federal parliamentary committee, which said the proposed laws fell short on the privacy, transparency and oversight front.

Instead, the FRU morphed into a valuable intelligence tool for NSW investigators.

Everyday, they receive requests from officers investigating crimes, from a murder to a street brawl to a predator grooming a child online, for help to identify suspects.

The investigators provide an image, usually a still from CCTV but sometimes social media, that is then run against one million charge photos – images of people who have been arrested in NSW.

“One CCTV image can come back with 100 charge photos,” Senior Constable Anthony Pickering said.

This is where the critical human element comes in.

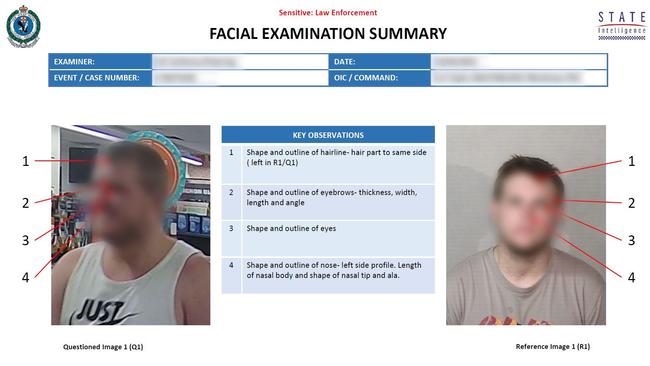

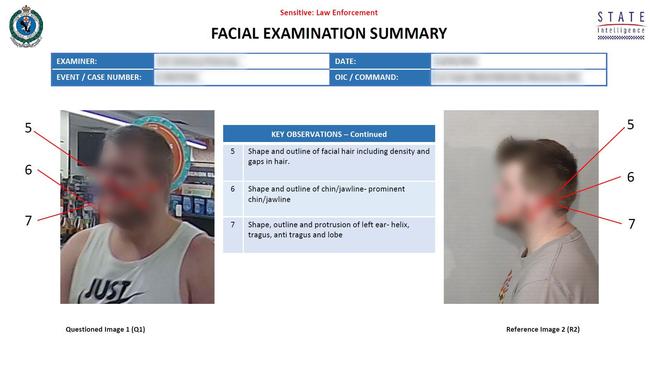

A FRU officer then physically compares every photo result against the CCTV or still image provided by investigators.

The officer breaks down nine components of the face.

Which angle do the ears protrude? Does the man have a widow’s peak? How thick are the eyebrows? Where does the hairline start?

“We are not persuaded by the investigators as to who it might be,” Sen Cons Pickering said.

“Most of the time they send it in blind. We don’t know who the person is.”

They never can definitively say the person in the CCTV is the person in the police database but they provide an opinion – support, limited support, elimination.

Once the potential match is assessed by a senior officer, a facial recognition summary is collated and sent back to the investigators.

“We are not saying it’s them but we say based on our training, it could be a specific person,” Sen Cons Pickering said.

“Then it takes the investigation down a certain path and it‘s up to them to corroborate it.”

PhotoTrac can also compile electronic line-ups for witnesses to pick out potential suspects.

Sgt Pickering, who receives about 20 or 30 requests a week, said facial recognition was an intelligence tool, not an evidentiary one.

It can’t be used in court to prove someone was involved in a crime but it can give investigators new leads to pursue.

“We don’t have too many eliminations when we are looking at different images,” he said.

“Requests that we didn’t get a potential hit from, they are a lot of the time based on the quality of the image or that the suspect hasn’t been charged before (so isn’t in the police database).”

There are also specialists within the FRU who create facial approximations based on decomposed remains or age projections, which was used in the case of missing toddler William Tyrrell.

In another recent case, police were given a photograph of a bikie who had been so badly beaten half his face was disfigured.

They didn’t know who he was or if he was dead.

“The facial guys cut his face in half and then duplicated that and ran that image through the database to see if they could identify him,” Mr Crandell said.

In the United States, tech giants Microsoft, Amazon and IBM have stopped selling their facial recognition technology to law enforcement following concerns about racial bias and misidentification.

Experts have suggested the technology misidentifies ethnic minorities and women more than any one else.

Asked how NSW could avoid issues with racial bias if other countries couldn’t, Mr Crandell said facial recognition couldn’t rely on the technology alone.

“For me, there must be human involvement,” he said.

“It‘s got to be a person that says out of those 15, which one is more likely? And I think that’s a good safeguard.”

Mr Crandell said face mapping had never been used to identify protesters in NSW because that was a legal activity.

“If an offence has been committed we would try to identify them by whatever means,” Mr Crandell said.

“But we don’t routinely go through to identify people at a protest.”

THREAT OF A ‘SURVEILLANCE STATE’

Australia needed to be cautious of moving towards a “surveillance state” with law enforcement able to dip into whatever data pools they choose, privacy experts have warned.

Digital Rights Watch has previously called for a moratorium on facial recognition technology, pointing to issues overseas with racial bias and misidentification. China uses facial recognition to suppress dissent – it has even fitted police with smart glasses which link to facial recognition systems.

Police argue that they are only using photographs of suspects in crimes as part of their facial recognition program but Digital Rights Watch program lead Samantha Floreani believes that is a moot point.

“As we keep building, essentially moving towards a surveillance state, there are lots of impacts on democracy and how we can live our lives,” she said.

“Regardless of whether or not you have anything to hide, there are many reason why people want to keep things to themselves.

“And we know increased levels of surveillance lead to high levels of conformity and self censorship.

“If we want a rich and diverse society and a thriving democracy where people can develop their ideas and push back when it comes to creating political movements we really need strong privacy protections.”

She said there were not enough privacy regulations in place that governed how police could use and share personal data.

“Law enforcement gets a lot of carve out from the federal privacy act and state based legislation that isn‘t necessarily a reasonable or proportionate measure,” she said.

“People should be able to participate in society drive a car and have a licence and be able to provide that information and trust it is used for the purpose it is provided for.”

Deakin University criminology lecturer Dr Monique Mann was wary of blurring lines between law enforcement and civil data collection, like the records kept by Roads and Maritime Services for a car vehicle.

“The thing I find most problematic about facial recognition is it acts as that conduit between an individual’s presence in physical space, their face and enables a connection to all of these other databases and information sources that might be out there about you,” she said.