How Corrective Services NSW’s electronic monitoring group keeps us safe

At a secret Sydney HQ the state’s worst murderers, rapists and pedophiles are monitored in real time after their release from jail. Take a look at the team keeping us safe.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

They are the killers, rapists and pedophiles living in our neighbourhoods. Offenders who have committed the most heinous crimes, yet the state has no option but to release them back into the community at the end of their often decades-long jail sentences.

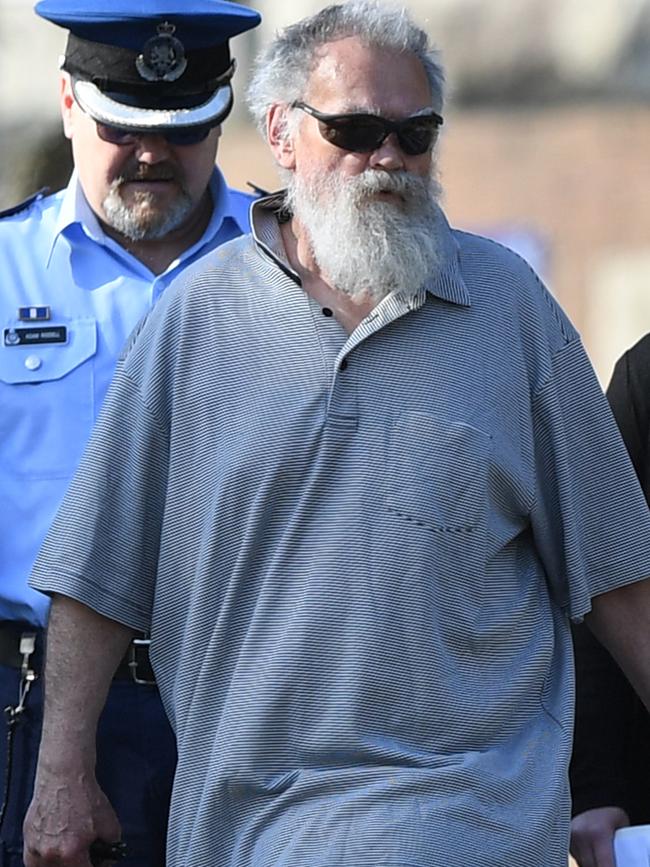

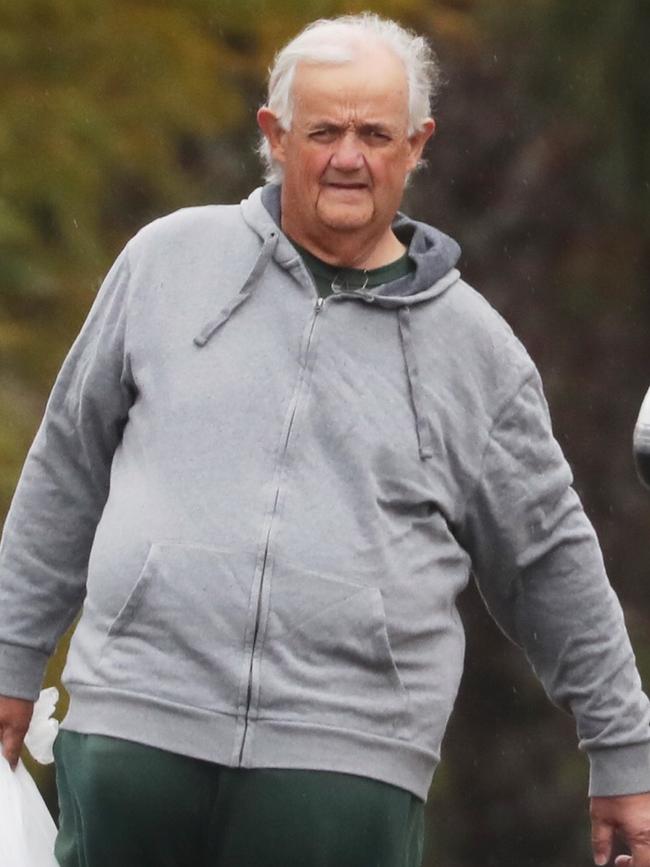

Notorious offenders like triple murderer Berwyn Rees; high-risk pedophile Brian Bowdidge; Outback killer Regina (formerly Reginald) Arthurell and Kevin Bou-Antoun, a cold-hearted rapist who tried to send a hit man after his teen victim after he was caught.

But there’s a catch.

They may be walking among us, but they’re doing so with a “virtual” team of Corrective Services NSW officers by their sides.

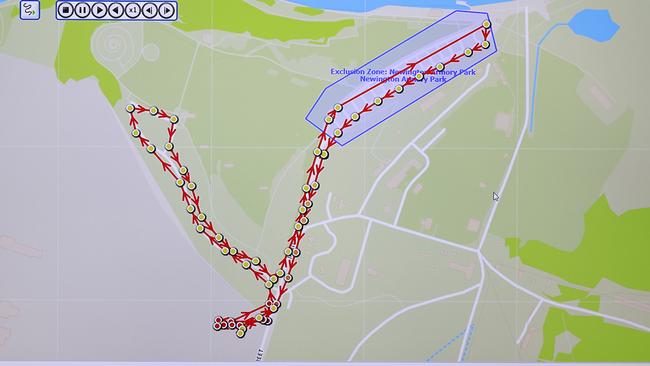

Officers know when they are home, when they catch a bus or train and via what route, when they go to the pharmacy to pick up a script or stop at the shops to buy groceries.

Importantly they know if they venture near the places they shouldn’t: a victim’s home, a school or playground, a banned business or workplace.

If that happens, the highly trained team swings into action, rapidly deploying supervising officers, police and other resources to protect the community from these predominantly male offenders, and in many cases to protect them from themselves.

Right now — and around the clock — a team of community corrections officers is watching over a bank of computer screens in a secret Sydney location, their eyes glued to “dots” that slowly move across the monitor.

Those “dots” are some of the state’s worst offenders, walking about in real time in their homes and communities, many of them household names because of their unthinkable crimes and the impact they’ve had on victims, families and entire communities.

There’s currently 55 of these offenders on Extended Supervision Orders (ESOs) in NSW — offenders who have been deemed by a Supreme Court judge to still pose an “unacceptable risk” to the community once they’ve served their sentences.

There’s strict restrictions on where they can go, who they can talk to, what they can do online, and more.

Supervising officers can drop in at any time to check up on them in person and, vitally, they’re fitted with state-of-the-art ankle bracelets which they must keep charged.

Andrew McClintock, the general manager of Corrective Services NSW’s electronic monitoring group, said the team had millions of dollars worth of surveillance equipment at its disposal.

The ankle bracelets are “waterproof devices with a hypo-allergenic external casing with multi-layer metal banding and fibre optic sensor,” Mr McClintock said.

“The offender is responsible for ensuring the device is always charged, so if we get a strap-off alert, we start escalating our response immediately.

“We know it would require a significant amount of force and a significant tool to cut them and remove them, so we know when someone takes them off there’s real intent to do so, and our response is commensurate with that level of intent.”

Offenders are placed on ESOs for up to five years at a time, but if they don’t comply, or reoffend, they can remain on them for decades, or face another term of imprisonment.

Bondi schoolgirl killer Michael Guider is back behind bars after breaching his strict supervision order last year.

Guider was released from Sydney’s Long Bay jail in September 2019, having served 17 years for killing nine-year-old Samantha Knight. Two years later, he was sentenced to a further three years’ jail for accessing child porn websites.

The expanded electronic monitoring unit opened in Western Sydney in early 2020 and is more than three times the size of the previous facility at Silverwater, with almost double the staff.

As well as the 55 offenders on ESOs, a further 710 parolees from across the state are currently being tracked via electronic monitoring.

Two-thirds are serious sex offenders whose monitoring is mandatory under legislation. Forty are domestic violence perpetrators, while 13 are victims — who are fitted with a paired device to ensure they are kept away from those who would do them harm.

Mr McClintock said while electronic monitoring was a valuable tool in supervising offenders, it was just one of dozens used in the management — and rehabilitation — of offenders.

“Electronic monitoring keeps person X in area Y, it can do that very well,” he said.

“But while it can manage geography, it can’t manage the behaviour of a person in their own home. It can just make sure they’re there when they’re supposed to be there.

“For some offenders, things like drugs or gambling underpin the offending, so a spiralling of those behaviours leads to new offences.

“That’s why if you don’t have all the other interventions and support, and you don’t work to understand the individual needs of people, then electronic monitoring is a less useful tool in lowering the rates of recidivism and getting people into prosocial activities — and away from anti-social activities.”

John (not his real name) has spent most of his adult life in jail, or as he puts it “in a cage”. So he relishes his freedom now his sentence has expired, even if it comes with strings attached.

All up, John’s been on an ESO for 15 years. It’s been renewed three times, the last time after he had a stint back inside due to historic charges.

This time though, he tells his supervising officer during a scheduled visit, things will be different. He’s a changed man, he told them during the visit observed by The Saturday Telegraph with his permission, and he intends to work his way down the levels of the supervision order.

First things first, he wants to pay a visit to extended family outside of his hard exclusion zone; then he’d like to get his ankle bracelet off; and ultimately be taken off the order completely.

He’s built a rapport with the two community correction officers who he sees regularly, at times unannounced.

For the first time in his life, he tells them, he’s in a stable relationship and has a home to call his own.

“I lived on the streets from age eight, I couldn’t read or write, I was feral. I didn’t have much of a childhood and then most of my life was spent in jail,” he said.

“You become institutionalised, you’re not sure what normal is outside of the cage.

“So I’m just working out what normal people do — what everyday life, everyday things are like.

“My offences were 30 years ago. I never had a home before, this is the first time in my life I’ve got my own bedroom, my own things. It’s all new.”

Officers have seen the change in him: a reduction in aggression, a calmer disposition, but moving an offender to lesser restrictions is never taken lightly or rushed.

During their visit, officers discuss his wish to move his curfew from 6pm to 10pm, so he can take his girlfriend to dinner and not have to rush home.

He also wants permission to travel to a family gathering up the coast.

It may seem like a simple request but it involves a high degree of planning. Officers will have to weigh up a range of factors and map out where John will travel through and to.

If John is granted his requests, and there’s no issues, officers say the removal of the bracelet might be the next step.

“I’m looking forward to that — it’s an indication that that part of my life, what I did, the mistakes I made — are finished.

“Yeah I did stuff up but it’s time to move on with my life,” he said.

“I don’t want to go back in that cage, I’ve lived in a cage long enough.”

Checking up on the worst offenders in the state would be daunting for many, not so for community corrections officers like Terry and Vanessa, although they wouldn’t like their surnames printed, to protect themselves and their families.

They’re a team, they back each other up. But they also like to think they can provide support and guidance for those they supervise, to get them back on track despite the hurt and pain they’ve inflicted in the past. To play some part in making sure they never do it again.

“You get to know them very well, and so it’s about figuring out how you can help them to change their behaviour so it’s more prosocial,” Vanessa said.

Despite the rapport they build with offenders, Terry says officers are never off their guard. During the visit to John, the veteran officer flicks through John’s phone — checking his call history, internet searches and any downloaded or received images.

And he casually asks questions — but there’s always a reason for asking.

“We’re always looking for red flags,” he says. “We don’t just listen for the answer, and what that might tell us, we’re watching their body language — and that of their partner’s if they have one.”

Officers have search-and-seize powers so they may sweep a house, garage and yard. They can conduct drug tests. They check out the neighbourhood, and the neighbours, to assess any risk.

“There’s been times when I’ve had people threaten to kill me, but that’s the exception to the rule,” Terry said. “It’s the skill of the officers, and the relationships they build, that is the key to success.”

The manager of the ESO team, Ingrid, said there’s no one-size-fits-all approach. Every one of the orders is different, “boutique” if you like, to address the unique offending of the individual who is thoroughly profiled and assessed by a psychiatrist.

“Community safety is our primary focus and we want to support these individuals to lead law-abiding lifestyles,” she said.

“Normally you do the crime, you do the time, and then on the expiry of your sentence you become a member of the community again.

“But in these cases, the risk of reoffending is still too high. Community protection is the priority.

“We’re not going to create model citizens, the goal is to prevent serious sex and violent offending.”

Got a news tip? Email weekendtele@news.com.au