Premier Henry Bolte showed no mercy for murder Ronald Ryan

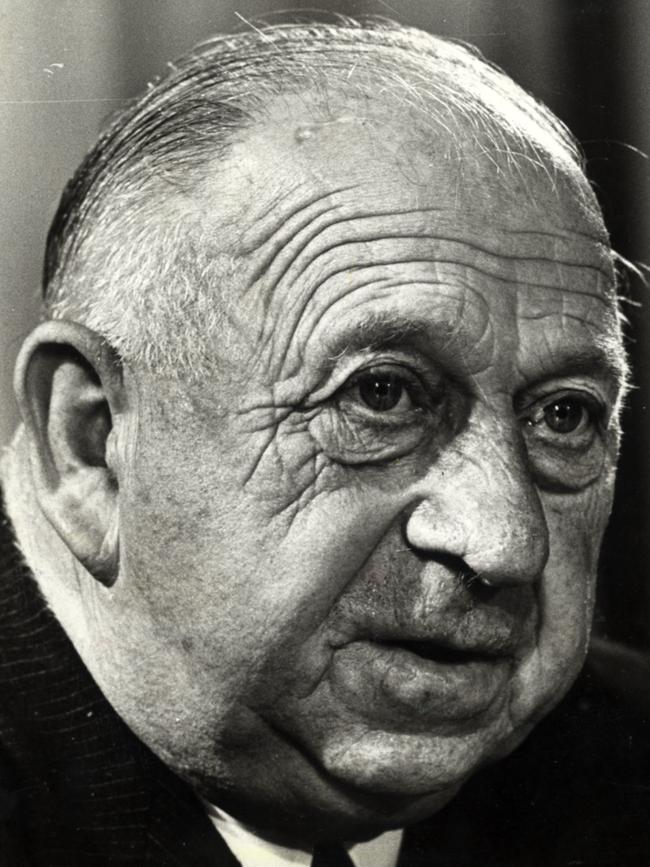

AS support grew for the end of the death penalty in Victoria in the 1960s, premier Henry Bolte tightened his grip on the state’s right to send killers to their death.

Our Criminal History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Our Criminal History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

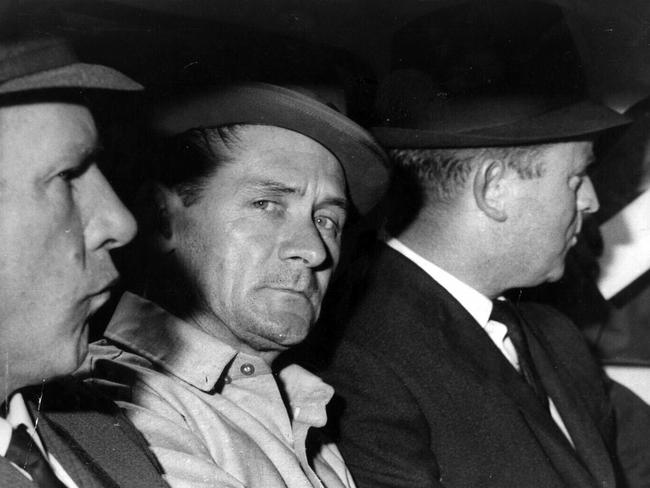

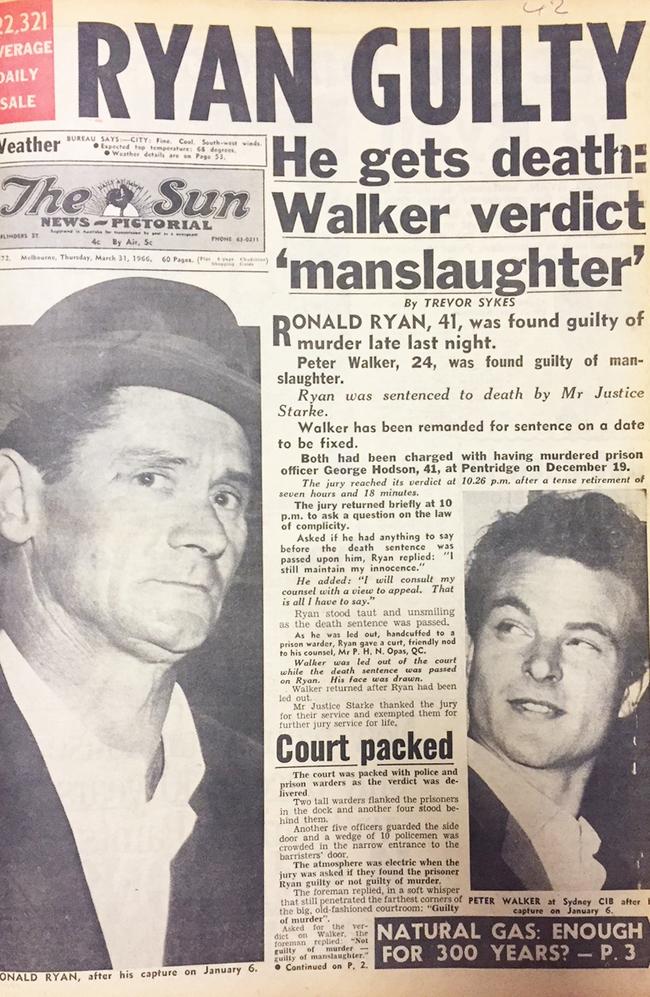

AT 8am sharp on February 3, 1967, Ronald Ryan was due to die.

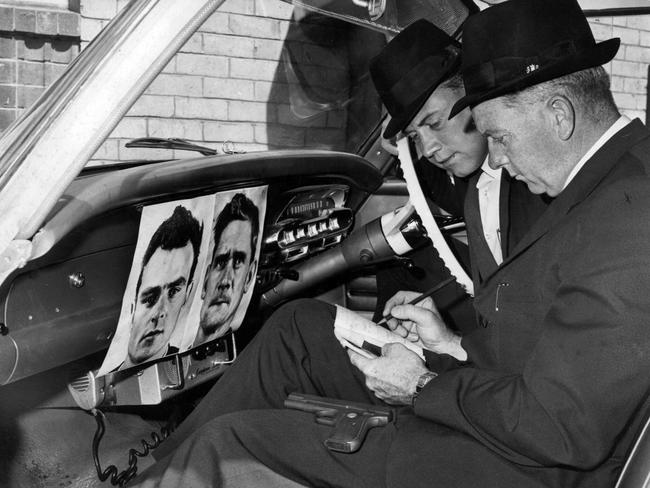

He had been handed the death sentence for the murder of prison guard George Henry Hodson during a brazen escape from Pentridge in late 1965 that had seen him and fellow inmate Peter Walker on the run for 19 days.

Now his final words, uttered to a hangman wearing a welding mask and a green cap, were “God bless you, make it quick.”

MORE MITCHELL TOY:

HOW MELBOURNE’S SHOPPING HEARTLANDS HAVE CHANGED

THE WATERFRONT WAR THAT CHANGED OUR WORKPLACES

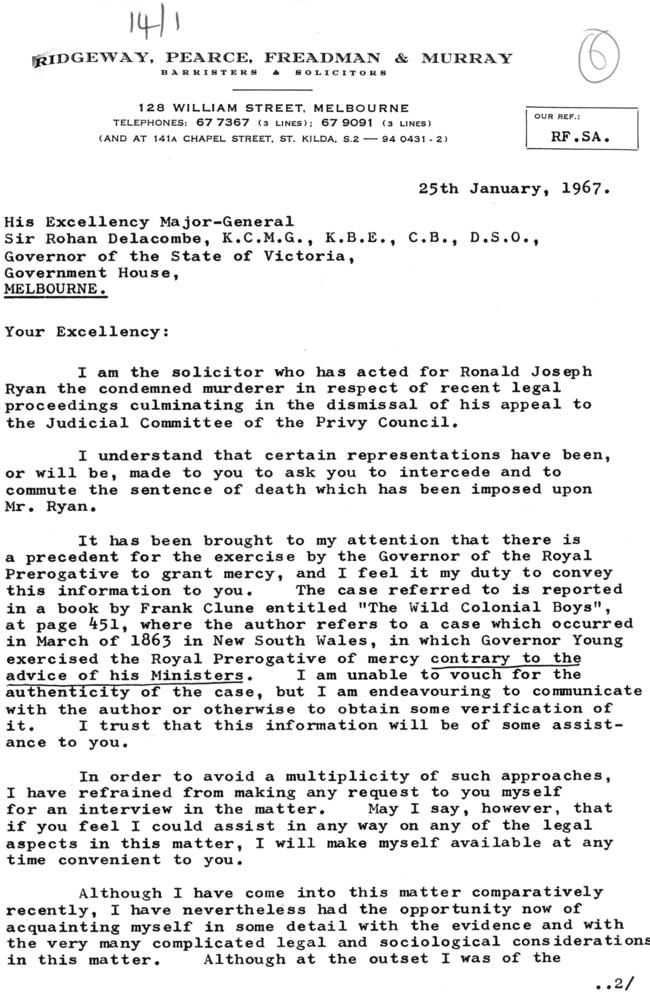

The night before, the governor Sir Rohan Delacombe had returned early from a holiday in Sorrento to Government House where an Executive Council meeting rejected Ryan’s final appeal.

Sir Henry Bolte, who had been premier for 12 years, was asked by the press what he would be doing at the moment of Ryan’s fate.

He replied, “One of the three Ss, I suppose.”

When asked to clarify, Bolte said, “A s***, shave or shower.”

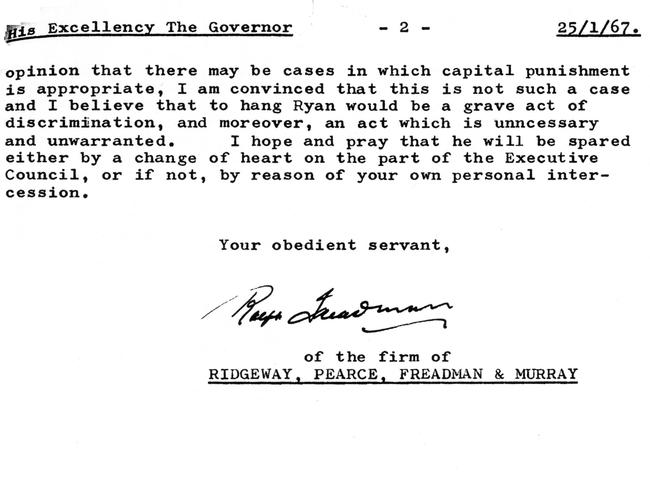

Bolte could have saved Ryan, but didn’t. Calls for a recommendation of clemency had been denied.

Nothing would thaw the premier’s coldness towards the killer, or others who faced the hangman’s noose in Victoria.

He had faced a tidal wave of dissent from churches, unions, the judiciary and the legal fraternity over his adamant support of capital punishment.

But his commitment to the state-ordered killing of those who had committed serious crimes would not budge.

THE HANGING PREMIER

HAVING been elected leader of the Victorian Liberals in 1953 when his predecessor Trevor Oldham was killed in a plane crash on the way to the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, Bolte formed a stable conservative government in 1955.

The Labor government of John Cain Snr was ailing from in-fighting and the deepening split which eventually formed the splinter Democratic Labor Party.

Bolte, a rural Liberal who hated Country Party members and who fostered an image as a simple, pastoral Victorian, was in some ways akin to Donald Trump.

His attacks on elite leftist intellectuals and the media were popular and his pragmatic, salt-of-the-earth leadership style and infrastructure-building policies resonated with Victorians.

He was also a staunch proponent of the death penalty, although when Ronald Ryan committed murder in 1965 nobody had yet been executed under Bolte’s premiership.

The last person to be hanged was Jean Lee — also the last woman ever to be executed in Australia — for a murder in Carlton.

THE TAIT AND RYAN CASES

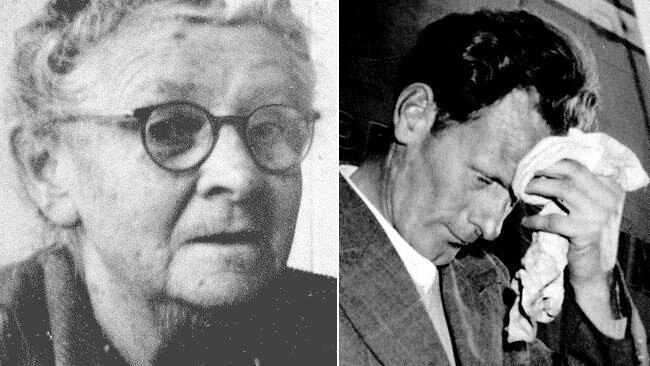

THE opportunity for a hanging came after the sexual interference and murder of 82-year-old Ada Hall at a Hawthorn vicarage where her son was a priest.

The perpetrator, Scottish-born Robert Tait, had a history of violent crime and had served prison time in Queensland and Victoria.

He was found guilty of the Hawthorn murder and handed the mandatory death penalty, which premier Bolte was delighted to confirm.

Despite the depraved nature of Tait’s crimes, a petition was circulated to stop his execution with leaders in various Christian denominations, trade unions and community groups appealing to Bolte to recommend clemency.

Bolte would not grant it.

With every avenue available to Tait seemingly exhausted, including appeals on the grounds that Tait was insane, a final execution date was set after multiple postponements.

But there was one final appeal. The new 1959 Mental Health Act was set to come into effect on the same day as Tait’s execution.

That caused the chief justice to again postpone the execution pending a further hearing, at which Tait was found to be mentally impaired and the death penalty was commuted.

Instead Tait was imprisoned, never to be released. Premier Bolte was furious.

When the Ryan case emerged in 1966 Bolte refused to back down.

Again a nationwide campaign for clemency heaped pressure on the premier and attacks came from within his own parliamentary party and even his own cabinet to prevent the hanging of Ryan.

Bolte stuck to his belief that the state killing of Ryan would act as a stark deterrent against violent crime.

THE END OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

WHEN Ryan was eventually hanged, dying instantly as the rope tightened at Pentridge in February 1967, there was a national outpour of anger and sadness.

But despite moral criticism Bolte’s position proved to be electorally popular.

In the 1967 Victorian election he was returned to power with a crushing defeat of long-time Labor opposition leader Clive Stoneham with six seats passing to the Liberal Party.

That reduced the Labor Party to just 16 seats and the Country Party, then not in coalition with the Liberals, to just 12 seats.

Bolte’s support of hangings was a key part of his election success.

Ronald Ryan was the last person executed in Australia.

Despite Bolte’s win in 1967 the following election saw him returned with a reduced minority and in 1972 he resigned to make way for his Liberal successor Dick Hamer, who went on to win three more elections.

The death penalty was abolished in Victoria in 1975, eight years after Ryan hanged.

Originally published as Premier Henry Bolte showed no mercy for murder Ronald Ryan