John Dunn - cop killer and one of Australia’s first declared outlaws

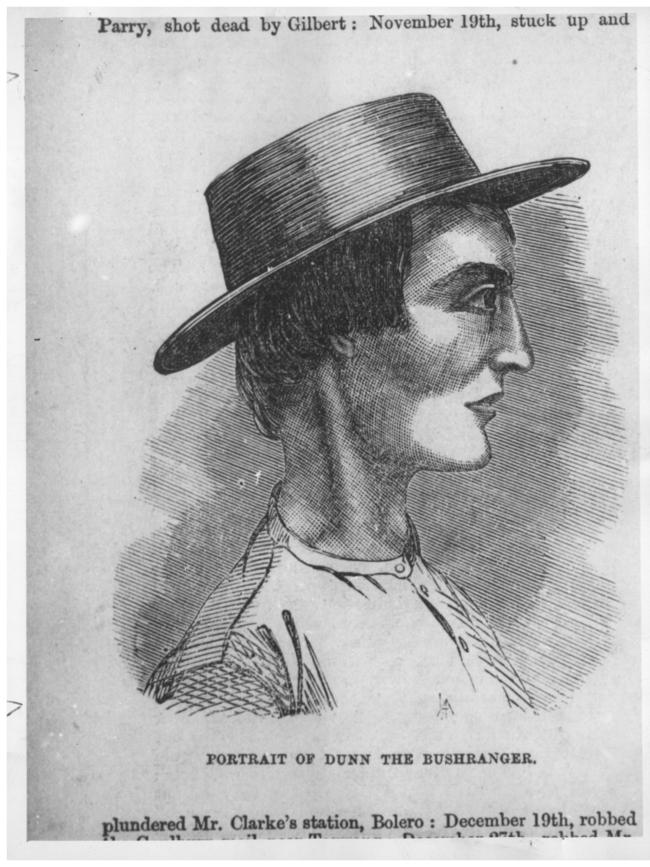

HE was only 19 but John Dunn became one of Australia’s first declared outlaws after he gunned down a policeman in broad daylight on a busy street.

At this time, when only a moment intervened between him and death, he clasped his hands together, and not a quiver or tremor of the limbs betokened that he was afraid to die. He died indeed like a penitent Christian, without fear, and without bravado. - Queanbeyan Age, March 19, 1866

HE may have been brave as he stood at the gallows inside the walls of Darlinghurst Gaol in central Sydney on this day, but there was nothing heroic about Australian bushranger John Dunn who a year earlier shot and killed a policeman in broad daylight on a public street in NSW.

The 19-year-old’s murderous act as a member of the notorious bushranger gang led by Ben Hall, gave him the dubious honour of become one of the first men in Australia to be proclaimed an “outlaw” and thereby eligible to be shot on sight.

But just how he lived his life is as fascinating as how he went to his death with National Library of Australia files revealing the lengths police went to catch this colourful man who callously shot and killed one of their own in a spot still marked today by a plaque, a tree stump and a pub that was the backdrop to the crime.

Back in the 1800s there were five hotels in the township of Collector — about 35km south of Goulburn in the NSW southern tablelands off the highway to the pastoral lands that would one day become the nation’s capital, Canberra.

True Crime history: The astounding story of Captain Moonlight

True Crime history: Grisly tales from the gallows

Collector was a popular staging posts on route to then major inland towns like Goulburn and Yass, and then like today to stop and take an ale.

Prominent among the pubs was the Kimberley Inn, built in 1860, which still stands today but was renamed more recently “The Bushranger” to commemorate a night of madness on January 26, 1865 that put the village on the map.

THE PRELUDE

Hall, Dunn and a third accomplice John Gilbert had been creating havoc in the district bailing up travellers and homesteads to loot at will. In one day about 30 people were robbed at gunpoint of clothes, boots and other valuables including watches, guns and saddles.

The men were resting in the shade of a stand of trees with hostages, whom at gunpoint they had ordered to prepare them a meal, just outside the village when a local judge, Frederick Meymott with an escort of two police troopers passing through the area, accidentally came across the trio.

“Here’s a bastard trap,” Dunn, who was on look out, called out to his accomplices using the slang for a policeman. His reaction was overheard by the hostages and later reported by Judge Meymott in a personal letter he wrote his brother two days later about that day, the manuscript now housed by the National Library of Australia.

Gilbert responded that they would “face him” but Hall saw the trap on horseback was accompanied by another so the trio fled rather than have to engage in a gun battle.

“A few moments after I had joined the bailed-up party, my troopers returned, having lost sight of the bushrangers in the thickness of the bush,” Judge Meymott wrote. “When the police heard who the men were, for they did not and could not know before (especially as they were fully a mile ahead when the trooper first saw them), they were desirous of going in pursuit.”

The judge’s party however was convinced to instead go to Collector where they were told a police team was to be assembled to hunt the gang. The team led by local magistrate, a Mr Voss, had indeed been assembled and had set off in pursuit as the judge went on his way. The trio however were waiting outside the village and on seeing the hunting party leave, shortly before 6pm made straight for the Kimberley Inn, also known as Kimberley’s Commercial Hotel.

At this stage they had taken a young lad hostage, Henry Nelson who was on his way back to Collector from Taradale and whose father happened to be 38-year-old Samuel Nelson, Collector’s only constable.

At arriving at the Inn, the three men dismounted and ordered Henry to hold the horses. According to an account from the day, the lad was told they would “blow his brains out” if he let one of them go so he diligently kept a tight grip on the reins as he watched the drama unfold.

Hearing a disturbance, Inn landlord Thomas Kimberley, sitting in a room off to the side of the bar, went to the door where he was greeted with a “pepper box” revolver pushed deep into his chest. He was initially pushed in before he and others in the bar were ordered to line up along the outside wall of the pub as Hall and Gilbert ransacked the building. With all authority out on the hunt they had no fear they were going to be disturbed before they could make off.

Dunn was posted outside but minutes later saw the district’s clerk of petty sessions riding into town on horseback so he too mounted his nag and took off toward him firing his gun before turning back toward the inn to warn the others.

“Call Ben Hall down stairs,” Dunn said to those outside.

A reporter’s account from the later court trial and witness statements best record those moments after.

“Hall came down with two guns in his hand, one of which he gave to Dunn, saying, “You go outside, you can manage them, Jack.”

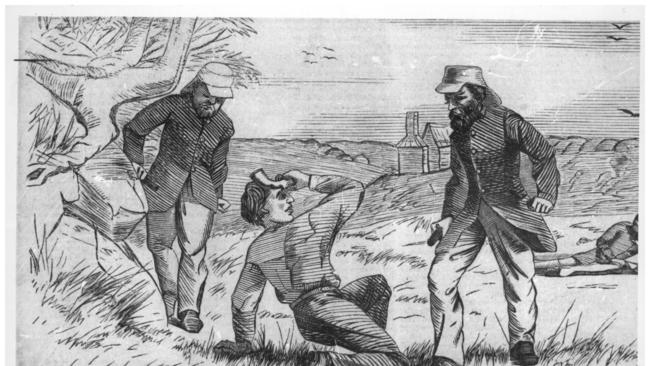

Dunn went away a second time on horseback, but retuned and warned the boy not to let the horses go. He went down to the corner of the fence and bent down, his hand holding the gun, being on the ground. He had not been in this position long, before Constable Nelson (the only constable in town) approached by the road from the township along the fence, armed with a carbine and fixed bayonet. When about ten or twelve yards off the corner where Dunn had placed himself, Dunn jumped up exclaiming, “Stand! Go back”, almost immediately firing a shot from the revolver. Nelson staggered a few paces towards the prisoner, who then fired from the gun, and Nelson fell. Frederick Nelson, his son, who had followed his father, was close to the spot just before this happened, and was pursued by Dunn but managed to escape from him. This occurred about dusk. Dunn then returned to the front of the house, saying, “I’ve shot one of the bastard traps, the other has bolted.” Hall, who, with Gilbert, had come out of the house, said they had better go and see who it was. Gilbert took Nelson’s belt saying, “It’s just what I wanted, I’ve burst mine.” And Dunn took his carbine. They then fetched a lot of things out of the house, boots, clothes etc, packed them upon the horses and made off. Nelson’s body was brought to the inn, life being extinct.”

THE SHOOTING

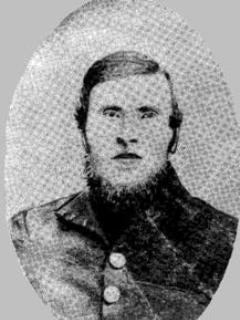

Samuel Nelson was born in Oxfordshire in 1827 and with his wife Elizabeth Goode and four children Frederick, 6, Henry, 4, Jonas, 2, and Matilda, born at sea, arrived in Australia on the ‘Parsee’ on 17th January, 1853.

The couple could both read and write but Nelson listed himself as a labourer and moved to Darling Downs in what is now Queensland. In August 1857 his fate was sealed when he joined the NSW Police, went on to have another five children and was posted south to Collector.

On the day of his death he was out chopping wood when he received a report from a village girl the Inn was being held up.

“Now I am just going to do my best,” he told his wife, then eight months pregnant, as he collected his police-issue single shot carbine with the bayonet and his belt and walked out the door toward the pub. She pleaded with him not to go alone but there was no-one else about.

The 18-year-old Frederick saw his father walking to the pub and followed. He later recounted to authorities what he saw.

“When my father got near a fence close by the house, a bushranger sprang from behind the fence and called to my father to stand, and fired immediately afterwards, on which my father staggered into the road and called out “Oh!”. the bushranger fired again, and my father fell; I was inside the fence at this time, and about ten yards from my father; the bushranger called on me to stand, but I ran away, on which the bushranger fired at me, but did not hit me; it was light enough for me to see, but not to recognise the man who shot my father; I spread the alarm through the township of what was going on, and after a while my brother came and said that the bushrangers had gone, on which I went up to Kimberley’s and found my father’s body had been taken inside the house; he was quite dead; while this took place my brother was compelled to hold the bushrangers’ horses outside Kimberley’s house, having before this been compelled to march there, a distance of three miles; when my father fell I heard his carbine fall from his hands on to the ground.

A post mortem confirmed Constable Nelson was shot once in the face and once in the heart with 20 other shot marks around the main wounds. He had died almost instantly.

Dunn raced back into the Inn and fetched the others. Hall had been upstairs where at gunpoint he had taken a servant at Kimberley’s, Eliza Mensey, to help him ransack the premises. He was downstairs in the main bar area with his loot when the shots were fired.

“I went upstairs with one of the bushrangers with the keys to open the drawers; he remained there a few minutes and conversed with me; he told me his name was Hall, and that the man outside on guard was Dunn; I was standing on the step outside the front door when the shot was fired; the man who fired the shot was the man Hall called Dunn.

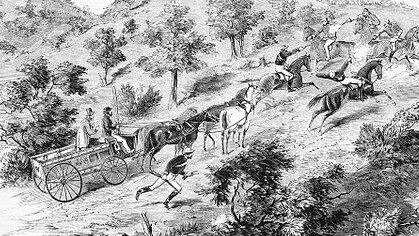

After the shooting, the trio quickly grabbed their horses and rode hard. The police, who had earlier set off to track the men, sighted them once on the brow of a hill and charged at them but with the failing light they escaped. News spread quickly through the NSW colony of the action at the village of Collector with local observers at the time noting “the outrages had caused great excitement” but obviously not of the good kind.

“This news, of course, created some excitement, but I am pleased to say, no weak, foolish fear among the household,” Meymott recorded in his now archived letter as he sheltered at Irish-born squatter Terence Murray’s homestead near Lake George. It was Murray and his father who had settled the region when they were granted land in 1829 and went on to pioneer the district.

“All the available men and arms were, as speedily as possible, collected, the entrances secured, and watch was kept by turns all night. About ten yesterday, the police came to Mr. Murray’s, to escort me onwards; but as the bushrangers were still hovering about in the neighbourhood, I thought it best not to take away two out of the three policemen in the place, and that it was much better for them to stay where they were, in case their services might be needed. So we kept watch, and were all day under arms at Mr. Murray’s, and the police kept a good lookout about the town; but all remained quiet.

This morning I heard of one report, that the gang had come on this way with the determination of attacking me for interfering with them the day before; but another report seemed to be more likely to be correct, viz. that they intended to waylay me and see me safe on the road for some miles with the police, and then to go back and finish robbing the town.

I left Mr. Murray’s about 10.30am with the two troopers and a civilian who was coming this way … and I think it very possible … that the gang would return to finish their work at Collector. If they do, they will meet with a warm reception, for special constables have been sworn in, and everybody round is prepared to give them battle.”

But there would be no battle, not that week anyway, with the gang heading elsewhere at pace.

A rotting tree stump at the side of Kimberley’s (Bushranger Hotel) was possibly a fence post from where either Nelson approached and was fatally shot or the spot from where Dunn hid before firing; history is now sketchy of the either or both but the tree stump-post is there as is a large memorial to commemorate Constable Nelson’s death on that spot.

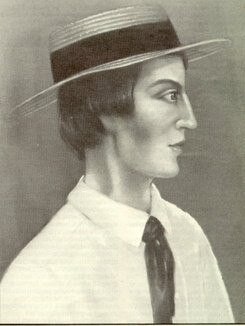

THE KILLER

Dunn was born at Murrumburrah near Yass and was a small youth, a ploughboy, who worked as a jockey before he fell foul of the law by robbing a Chinese gold miner as a youth. Dunn’s parents Michael and Margaret Kelly, who married when she was 17 and were both convicts, lived on an impoverished farm with only a small income from her working as a servant to a nearby rich landowner. Dunn was the eldest of nine children and his prospects were never going to be good although he could read and write and was a champion jockey known in the Yass district for his riding.

Dunn was just 17 when in October 1864 he joined Hall and Gilbert to replace another member who had been shot and captured by police. Hall was a hero to some, and Dunn took little convincing from Gilbert to join them in the excitement they were causing in the district and the lure of money to be gained from heists. His grandfather also encouraged him to join the group. Within a day he was immediately exposed to the gang’s ways with a series of armed robberies. While most his age wore old clothes and walked everywhere Dunn was now riding his own horse, albeit stolen, wore the best outfits and when he wanted something he could steal it at gunpoint.

Newspaper clippings of the day showed the gang robbed a group of travellers near Goulburn on October 24, a local station three days later, the Albury mail coach on October 28th near Jugiong Creek village west of Yass then another station at Yass, then the Yass mail run, then it was back toward Goulburn for its mail run and a couple of nearby stations. By this stage Hall had been bushranging for more than two years and was adept at evading capture, sharing the spoils and enthralling towns he raided earning himself the moniker of the “gentleman bushranger” who consistently claimed to all it was that being wronged by police that set him on the payback path, robbing and taunting police with his infamous call “you’ll never take me alive”. In truth, it was his association with a then another notorious bushranger Frank Gardiner that saw him go from a modest grazier to an armed robber.

When Dunn joined the bushrangers, his father Michael Dunn reportedly rode in search of him in the hope of rescuing him from “an evil life” but his horse died from overexertion and he was compelled to return home from his unsuccessful mission.

On November 15 Dunn was then exposed to the gang’s true murderous ways when they robbed the Gundagai mail coach near Jugiong which had an armed escort and so ensued a fierce gun battle. Gilbert shot dead one officer, a Sergeant Parry. The death did not deter the gang as they went on robbing, kidnapping and even burning down a property they had ransacked. Dunn for his involvement in the Jugiong robbery earned a bounty on his head of 500 pounds. It would eventually go up to 1000 pounds for the man dubbed the “baby-faced bushranger”.

That Christmas all the men spent the day with Dunn’s family who had apparently accepted his new life, and no doubt a share of his loot. The gang’s infamy had been set but in nearby Binda the gang publicly danced and sang at the local Flag Hotel, with an armed Hall reportedly standing by the door to stop anybody who had thoughts of reporting his two friends to police as they had a good time and claiming a reward. No-one did. Their brazen ways was a mark of how they carried out their raids.

THE END OF THE GANG

After Collector the men laid low for a few weeks with their next confirmed heist on 6th of February where they again bailed up the mail coach just outside Goulburn and two weeks later, wanting faster horses, robbed a stud of three racehorses. The pillaging then continued in earnest, stations, stage coaches, public houses and dray teams of labourers. At Araluen they attempted to hold up the gold run and after shooting a policeman made off empty-handed with three other officers in pursuit.

Their exploits and notoriety was growing to the status of legendary, with the trio robbing almost daily to the point that in a February 1865 local Yass Courier newspaper clip report recorded the bailing up of the Newbriggen Inn at which “extemporised a soiree dansante, compelling everyone in the neighbourhood to join the gay and festive scene”.

But the merry dance was coming quickly to a close.

Early in that year authorities decided to introduce legislation that was seen as radical, then and now, to bring an end to the gang. The Felons Apprehension Act effectively declared the trio as being “outside the law” and therefore outlaws that could be killed by anyone, citizens or police, at any time.

The Hall gang had committed more than 100 robberies between 1863 and 1865 so the legislation was quickly passed by the NSW Parliament in a bid to end their reign of terror. Dunn, Gilbert and Hall were cited although the latter never killed a man but was the leader of a gang that did. In Victoria, an adopted version of the Act would later go on to cite the Ned Kelly gang as outlaws.

The men on hearing about the open bounty on bushrangers’ heads decided to head north but needed fresh horses and provisions for the long ride. They were northwest of Forbes when a local about Goobang Creek promised to help them but instead reported them to police. The trio split up but agreed to meet back at the creek where police were also waiting for them.

On April 29, a fortnight after the law was passed a summons was formally issued calling on the trio to surrender but it was ignored.

At dawn on May 5 Hall returned to the creek and was shot dead by five police with at least 30 rounds in his body. As he fell and, as he held himself up by a tree he reportedly cried, “I am wounded; shoot me dead” and then fell dead. With delays in the reporting of his death the trio were not formally declared outlaws by name until May 10.

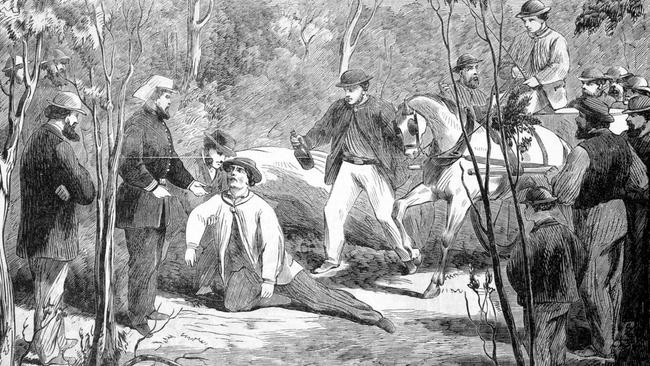

The other two heard the news and headed for Dunn’s birth village of Murrumburrah. Anticipating he would head home, Senior Constable Charles Hales from nearby Binalong police station headed that way too. They approached Dunn’s grandfather John Kelly who reportedly in a drunken stupor told them where his grandson would be later and he was promised reward money if he sold the pair out.

On May 14 Dunn and Gilbert were fronted firstly inside Kelly’s Binalong home by four police. They had surrounded a house but Kelly had a change of heart and yelled out, warning the pair of the troopers about the property. In a shootout and chase Gilbert was shot dead with Dunn able to escape despite being shot in the foot. He made one more robbery to steal a horse about Bogolong before going to ground for seven months.

On December 18 Dunn was recognised at Walgett and was chased and eight days later, after hiding at Quambone station, was again wounded this time with a bullet to the back in a shootout, which saw another police officer badly wounded, before he was later captured at nearby Coonamble.

Dunn was taken to Dubbo and held in police barracks where his wounds were tended to but on January 14 he escaped only to be found the next day by a nearby river, too weak to travel any further. He was then taken to Sydney to be tried where there was great interest in the “young scoundrel and his performances” as the local papers described him and his exploits.

He was tried before Chief Justice Sir Alfred Stephen and found guilty of the murder of Constable Nelson.

“Was it nothing to you to shoot brutally, and murder a poor man like that? Talk of bravery- I know no greater bravery than was displayed on this occasion by Constable Nelson. The town was deserted by the police, who had been put upon a wrong scent, and he was left alone. A little girl tells him the bushrangers are at Kimberley’s and what does he do? ‘I will go down and see what I can do alone’, such a sentiment can only be equalled by his namesake, who expected ‘every man to do his duty.’

Nelson went to do his duty, and met his death; it was a most brutal murder, and it is impossible for anyone to sympathize with you. The unhappy man is not only shot dead, but you at once return to your companions, and the others who were at your peril and made use of the most filthy expressions, you talk in this beastly and insulting way to men whom you had covered by revolvers, and firearms pointed at their heads, spoke to them insultingly when they were helpless- That was your courage and here is your bravery.”

Dunn was hung for his deeds, the death bell tolling at 9am by which time a large crowd had gathered. According to the Queanbeyan Age:

“As they walked towards the scaffold the prisoner repeated in an audible voice the prayers after the Rev. Father McCarthy. Owing to the wound received at his capture, the unfortunate man limped along painfully, but still he bore himself bravely up, and appeared as cool and collected as any of the spectators. At the foot of the scaffold, Father McCarthy bade him adieu, and he dragged himself up the ladder, accompanied by the Rev Father Dwyer, who remained with him to the latest moment. When the rope was adjusted round his neck, he still continued to pray, and his lips were moving when the white cap shut out from him the crowd who faced him and the bright sunshiny morning …. an unusually large number of people assembled to see him hanged, and amongst them was a man who came from Windsor for that purpose. The spectators, amounting to about seventy, were deeply impressed with this last act in the career of Dunn.

“After hanging the prescribed time, his body was cut down, put into a coffin provided for him by his godmother, Mrs Pickard, and then carried to the hearse outside the gaol walls, where it was received with wailings and moanings from a great number of women collected there. Mrs Pickard, with the dead man’s brother and his uncle, followed the body in a mourning coach, which proceeded to the Catholic burial ground, near the Railway Station. The rites of the church having been duly performed, the body was interred amidst the tears and groans of a very motley lot of people, old women prevailing, the majority of whom seemed to have but little regard to the precept of the Apostle, that, “Cleanliness is next to Godliness;”.”

The article of his death sat alongside two other reports of unrelated bushrangers creating havoc and bailing up at gunpoint travellers in the district. Lessons were not being learnt.

Before he died Dunn told gaol authorities he blamed Hall and his then cohort James Gordon, known as “Old Man”, for convincing him to leave his parents and ride with them. But he had no such regrets or blame as he terrorised the district.

At least two of Nelson’s children, Frederick and Jonas, became police officers and went on to have successful careers. His wife Elizabeth died at the age of 85 in 1914 leaving behind her eight children, 44 grand children, 14 great grand children and 5 great great grand children. At least one Dunn descendant also became a NSW Police officer.

Nelson was reportedly buried in the rear yard of the local police station soon after his death and post-mortem but was apparently exhumed 50 years later, without the knowledge of family, and reburied at the local cemetery alongside the Inn owning Kimberley family. Records of why the move was done remain unknown.

A pistol supposedly once held by Ben Hall hung on the wall of the Kimberley before it was stolen several years ago.