Grisly tales from the gallows revealed

THE closer the hangman got to the crowds on the riverbank, the more enormous and repulsive he seemed. Women gasped and children screamed, the ‘thrill of horror creeping through their veins’.

Our Criminal History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Our Criminal History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

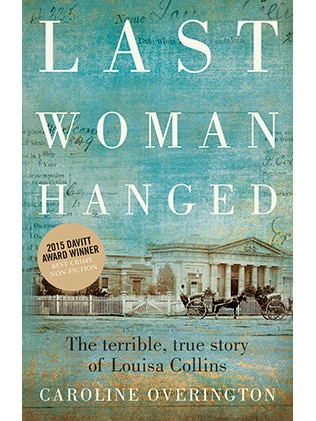

WHEN Caroline Overington set out on a five-year project to research the potential injustice that saw Louisa Collins hanged for murder after an unprecedented four trials she felt “blessed” that so much material from the 1880s had been preserved.

Louisa’s case — brought after arsenic poisoning was alleged in the deaths of her first and second husbands — was incredibly unusual and became a catalyst for the campaign for women’s rights in Australia, but was it fair?

Despite the fact that there “was no murder weapon, there was no real motive, there were no witnesses”, the odds were stacked against the mother of ten, who was given a barrister “who became the first barrister in NSW to be struck from the role for incompetence,” says Overington.

Three juries failed to convict, but a fourth found her guilty and Collins died on January 8, 1889 in a botched hanging that nearly tore her head off, leaving a gaping wound in her throat.

Her horrific end was far from unusual for the times though.

“Hanging is a terrible way to die and there were multiple accounts of executions that went terribly wrong across New South Wales and across the other states,” Overington says.

“It’s not a precise science. You have to do a lot of mathematics, if you will, about the length of the rope, the height of the gallows, the weight of the body, and it’s not precise, you can’t predict how a body will react, whether the neck will break, whether the flesh will tear.

“Louisa’s case was unusual in that she was the first woman and the last woman to be hanged at the Darlinghurst jail (in Sydney), and they really didn’t have much of an idea how to deal with a woman whose body is different.

“They had in mind that if she was hysterical — because the idea was that she might be hysterical — they could perhaps strap her to a chair and hang (her on) the chair.

“To our mind today (it’s) completely barbaric. In my view it was barbaric then too. I mean she died a terrible death. They didn’t see it that way because they saw it as confessing your sins and being sent back to your maker, but it must have been terrifying.”

In the following extract from Last Woman Hanged, Overington describes another brutal death at the hands of the authorities that shocked even the far less delicate sensibilities of spectators of the time.

BOOK EXTRACT:

Capital punishment had, regardless of gender, been the standard response to the crime of murder since the arrival of the First Fleet. The preferred method was hanging, which was for years done before crowds of enthusiastic onlookers, and often with startling ineptitude. Take, for an example, the first public hanging in the colony of South Australia. Given it was the first, mistakes were bound to happen — but still. The year was 1838, and the condemned man’s name was Michael Magee. He was twenty-four years old and had been brought to the court in clanking irons, accused of firing a shot at the local sheriff, Mr Samuel Smart. The shot missed, leaving nothing but a gunpowder graze on Mr Smart’s cheek — but the judge decided that Magee should hang.

Three immediate problems arose.

First, Magee was a Roman Catholic and would therefore need to see a priest before he died, but there seems to have been no Catholic priest in the colony of South Australia in 1838. The judiciary pondered this problem for a day or so before deciding that a local tradesman — fellmonger or blacksmith, the record does not say — would have to do (Magee reportedly agreed to this arrangement, not, one supposes, that he had much choice).

The second problem was more serious: besides having no Catholic priest, the colony had no executioner.

Again, the judiciary pondered. The sheriff’s name was mentioned, but given he had also been the intended victim of Magee’s poorly timed shot, this was considered ‘unseemly’ and so the job was put to tender.

Who, now, would take five pounds to execute Michael Magee?

Nobody came forward.

Who now will take ten pounds to execute this man?

Still no takers.

By the day of the hanging — it was a Wednesday — all of Adelaide was agog with curiosity. Would the execution go ahead and, if so, who would be the hangman? Everyone wanted to know and so, in the hours immediately after sunrise, at least 1000 people — women and children included — rose from their beds and began to make their way across fields to the hanging place to see what might happen.

Officials had decided that Magee should hang from a tree on the banks of the Torrens River. The tree was chosen both because it had a thick, horizontal bough over which the noose could be thrown, and because it was the only such tree on government land.

Perhaps because of the pretty location, many people had decided to bring picnics, and before long the riverbank was filled with spectators. Then, shortly after nine a.m., the mood turned serious: through the trees, people could see a procession leaving the distant gaol. (It wasn’t really a gaol; it was more a timber shed. A proper gaol wouldn’t be built for a year, and it would be run for decades by a man so fat that when he died his corpse would have to be carried out through a window.)

The procession comprised mounted police and a cart led by two horses, one in front of the other. Upon the cart sat a timber coffin — and upon the coffin sat Magee. If that were not bad enough, also sitting on the coffin was the hangman.

Who was he? Well, it was hard to be sure. To keep his identity a secret, the hangman had stuffed his clothes with padding, so he looked like he had a huge hump, and he covered his face with a horrible hand-made mask painted white around the eyes. The closer the hangman got to the crowds on the riverbank, the more enormous and repulsive he seemed. Women gasped and children screamed, the ‘thrill of horror creeping through their veins’.

FOLLOW: True Crime Australia on Facebook and Twitter

In an effort to keep people from crowding too close to the hanging tree, the judiciary had set up a temporary enclosure, like a sheep pen, around its base. They had also saddled an extra horse so the hangman could make a quick getaway after the job was done.

With Magee’s cart now parked inside the pen, the execution was, as they say, good to go. The noose was placed over Magee’s head and a cap was drawn over his face. Prayers were concluded. A motion was made that all was ready and then, after ‘a whip or two of the leading horse’, the cart upon which Magee still sat was drawn away. Many in the crowd shut their eyes, as well they might, because ‘here commenced one of the most frightful and appalling sights that ever perhaps will be again witnessed in the colony’. Either the horse was moving too slowly or else the hangman had bungled the noose, but instead of having his neck instantly broken, Magee started to slide gently off the coffin until he was hanging by his throat in the air, screaming, ‘Oh God! Oh Christ! Save me!’

Now it was time for men to gasp. The hangman — still in his mask and lumpy costume — got on the saddled horse and bolted.

‘Fetch him back!’ the crowd cried, so mounted police took off at full speed. Magee, meanwhile, was uttering the same piercing cries: ‘Lord save me! Christ have mercy upon me!’ Nobody knew what to do. Some cried, ‘Cut him down!’ Others urged the marines to shoot Magee dead with their muskets to at least put an end to his misery, and all the while, Magee’s hands were up the rope as he madly tried to save himself, while his body twisted ‘like a joint of meat before the fire’.

Finally, the hangman was brought back. Inspiration had struck and, with a ‘fiendish leap’, he threw himself upon Magee’s body and proceeded to hang himself from the condemned man’s legs, pulling him toward the ground until Magee could no longer cling to the rope and began to suffocate. By some counts, it took thirteen long minutes for Magee to die this way. Many in the crowd were horrified. Others waited for the body to be cut down and then carried on with their picnic.

• This is an edited extract from Last Woman Hanged by Caroline Overington, published by HarperCollins.