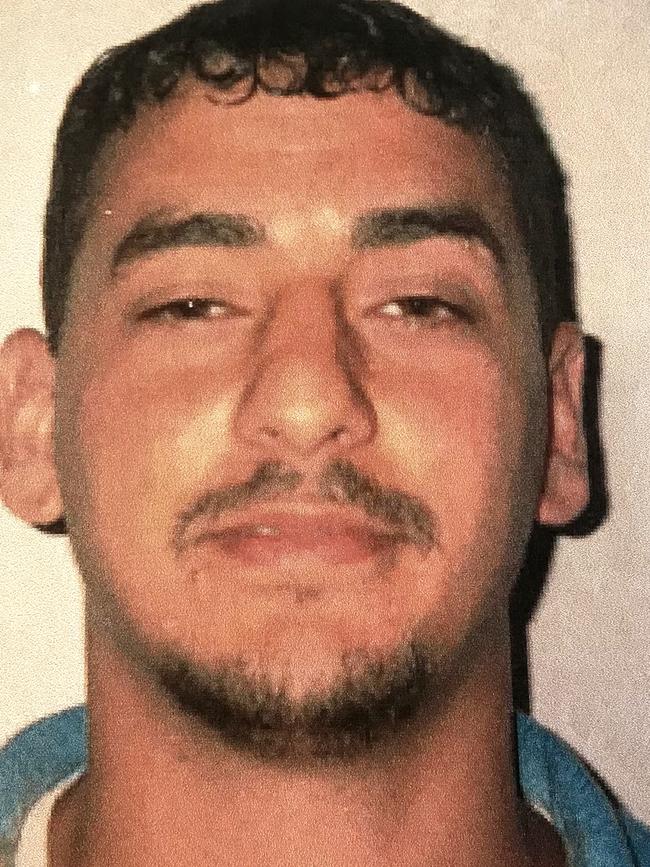

How Bassam Hamzy plotted bloodshed from prison cell 214

Bassam Hamzy wasn’t willing to take a hitman’s word — he wanted proof. Even if it meant cutting off the intended target’s finger and smuggling it into Silverwater jail to prove to Hamzy the hit on a Crown witness had been carried out. EXCLUSIVE MULTIMEDIA REPORT.

True Crime

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In part three of our four-part special on the influence of Bassam Hamzy, we reveal how even being locked-up wasn’t enough to stop his evil ways. While in jail he hired a hitman to kill a former friend, while also intimidating his own girlfriend.

Mistrusting of most people, Bassam Hamzy wasn’t willing to take a hitman’s word — he wanted proof.

Even if it meant cutting off the intended target’s finger and smuggling it into Silverwater prison to prove to Hamzy the hit on a Crown witness had been carried out.

Unfortunately for him, Hamzy didn’t know that the hitman he thought he was conspiring with to kill Khaled Hammoud in 2000 was actually an undercover police officer.

Transcripts of Hamzy’s evidence from the court case that eventually started his life behind bars reveal the arrogance of a man who endlessly tried to beat the system as the state’s most notorious inmate.

Jail did not stop his relentless scheming, from plotting to kill a Crown witness to smuggling mobile phones and cooking up fabricated evidence for a Lamborghini-driving cellmate.

After being extradited from Miami in the United States to Australia in 1999, Hamzy landed in Silverwater prison, Sydney’s holding yard from criminals awaiting trial or sentence.

By this stage, Hamzy was well aware Nedhal Hammoud, a friend who was with him when Kris Toumazis, 18, was shot dead outside a Oxford St nightclub in 1998, was helping police.

So was his brother, Khaled Hammoud, then 36, and Hamzy wanted revenge.

RELATED NEWS:

Part 1: Hamzy to mum: ‘Did you send me some undies?’

Part 2: What Hamzy’s handwriting says about him

Transcripts: ‘I want you to go and kick the f**k out of him’

Cell 214 in pod six was home for Hamzy and almost immediately he began breaking the rules and attempting to stamp his authority in the prison yard.

Controversially, he would later be at the centre of a complaint made against a prison psychologist, who was accused of having an inappropriate relationship with Hamzy while he was at Silverwater in 2000.

The complaint was made in 2002, after she resigned from Corrective Services NSW.

The woman is still working as a psychologist. Her brother, an alleged confidant of Hamzy, is currently accused of murder.

While on remand, Hamzy also had two mobile phones hidden in tins inside his cell and concocted a plan with an old criminal associate — a man known as Pham — to kill Khaled, a Crown witness.

On August 18, 2000, during a jail visit, Hamzy asked Pham to “rob” Khaled, which police said was code for murder.

“I said to him I wanted him to rob someone,” Hamzy later told the NSW Supreme Court.

“I told him he had to go to the wrecking yard, follow him from the wrecking yard after he gets home, to go and rob him.”

The target was Khaled and the aim was to “get everything he owned”.

While Hamzy claimed his plan was only to steal from Khaled, the police allegation was that he wanted him dead because he would testify against Hamzy.

Pham introduced Hamzy to a man named Jack, who was an undercover police officer posing as a hitman.

Hamzy wanted Khaled dead “ASAP” and needed proof. It was agreed one of Khaled’s fingers would be cut off after he was killed and brought to Hamzy in jail.

One of Hamzy’s associates Radwan Zraika was brought into the fold to drive Jack to Khaled’s work — Just Van Wreckers — and home.

Zraika, who survived being shot in the head in Chester Hill in 2017, was eventually found not guilty of conspiracy to murder.

MORE BASSAM HAMZY NEWS

How Hamzy began two-decade reign of terror

Night Hamzy’s blood reign over Sydney began

A secret listening device planted in the meetings between Hamzy and Jack helped ensure Hamzy’s undoing.

“So you don’t care how I do it, as long as he’s dead?” Jack asked Hamzy, according to transcripts tendered in court.

“What do you want done with the body? Do you want the body found or …”

Hamzy was recorded replying: “Doesn’t matter.”

He later told a court he finished that sentence with: “You can go and f**k his mother. All I want is the money.”

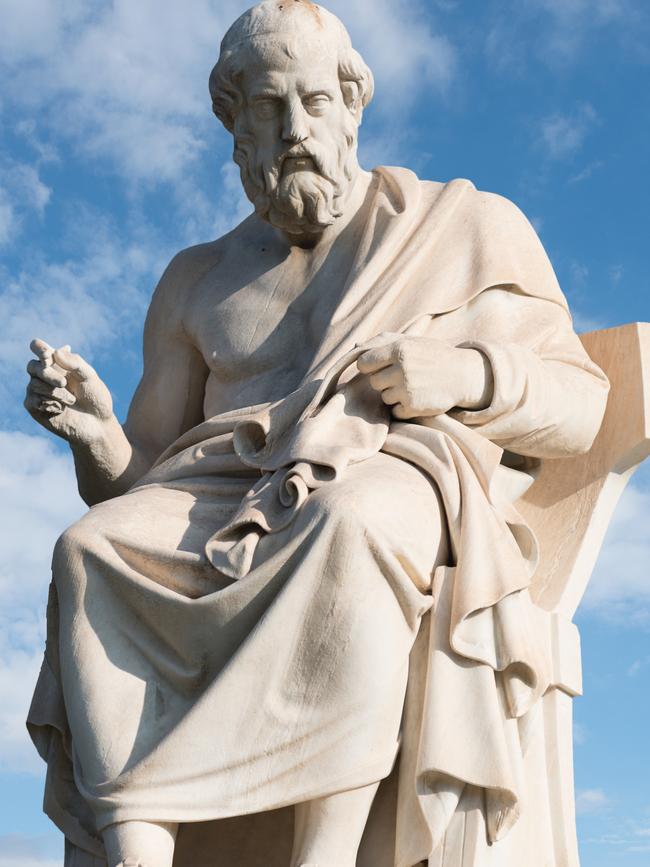

The behaviour and language was not indicative of someone who studied the work of the Ancient Greek philosopher, Plato.

But handwritten scribblings found in his jail cell in Miami, before he was extradited to Australia in 1999, suggested otherwise.

The notes — written from the Plato Collective Dialogue — included a reference to homicide and had Hamzy’s own barrister, Peter Bodor QC, perplexed.

“My Hamzy, you do not strike me as the sort who reads Plato for enjoyment. What was this about?” he asked.

Hamzy: “ … because it was boring I had nothing much to do over there, so I was getting a bit into the religion side of things.”

Hamzy said Plato’s philosophy didn’t contradict his own Islamic faith and he was curious as to why the philosopher wrote “that type of work”.

When the time came for Hamzy to give evidence about the homicide he was charged with, he blamed his friend Nedhal for shooting dead Mr Toumazis outside the Mr Goodbar nightclub.

Without flinching, Hamzy claimed Nedhal confessed to him about pulling the trigger in the bathroom of a hotel at Parramatta a few hours after the shooting on May 30, 1998.

“He told me he ran up the pavement … just on Oxford St and then he pulled out the gun and shot him.”

It was Nedhal, Hamzy claimed, who decided to go to Lebanon and Hamzy agreed because he wasn’t going to leave him “high and dry”.

The relationship soured after they arrived in Lebanon and Nedhal’s brother, Khaled, convinced him to return to Australia and speak to the police.

“I got sus on him, I started getting sus on Nedhal,” Hamzy told the court.

Nedhal had already pleaded guilty to accessory after the fact to murder and received a heavy discount for turning against Hamzy.

He told police it was actually Hamzy who confessed to using his gun, which he had shoved in the waistband of his pants, and later threatened Nedhal, telling him “we’re all in it together”.

Hamzy’s evil self-preservation knew no boundaries.

He even instructed friends to stand over his own girlfriend outside jail to make sure she falsified evidence for him.

In June, 2000, Khalid Kaddour was in Silverwater jail after crashing his Lamborghini during a wild ride through Sydney’s northern beaches 18 months earlier.

He slammed into an oncoming car and left a woman with such severe injuries she was hospitalised for three months.

Kaddour ended up sharing a cell with Hamzy and the pair bonded over smuggled mobile phones.

Ahead of Kaddour’s trial for dangerous driving, Hamzy agreed to fabricate a defence for him.

Hamzy ordered his girlfriend go to Kaddour’s solicitor’s office and swear an affidavit stating she was a passenger in another car that caused Kaddour’s crash.

When the girlfriend expressed her hesitation, Hamzy sent his mates around to stand over her and take her to the lawyer’s office.

Like history repeating itself, Hamzy’s knack for falsifying affidavits to exonerate friends from criminal responsibility would emerge almost two decades later.