How three very different crims gave themselves away

ONE wrote an extortion demand, another a love letter — in both cases leaving a vital clue for police. The third bizarrely penned a note directly to officers in a murder case — but it was his triple-0 call that really brought him unstuck.

Crime in Focus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime in Focus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

DNA and new CSI-style techniques have provided vital evidence in Australia’s fight against crime, but it’s not always that complicated. In these cases the key clue was right under detectives’ noses — in black and white — or in a distinctive voice at the end of the line.

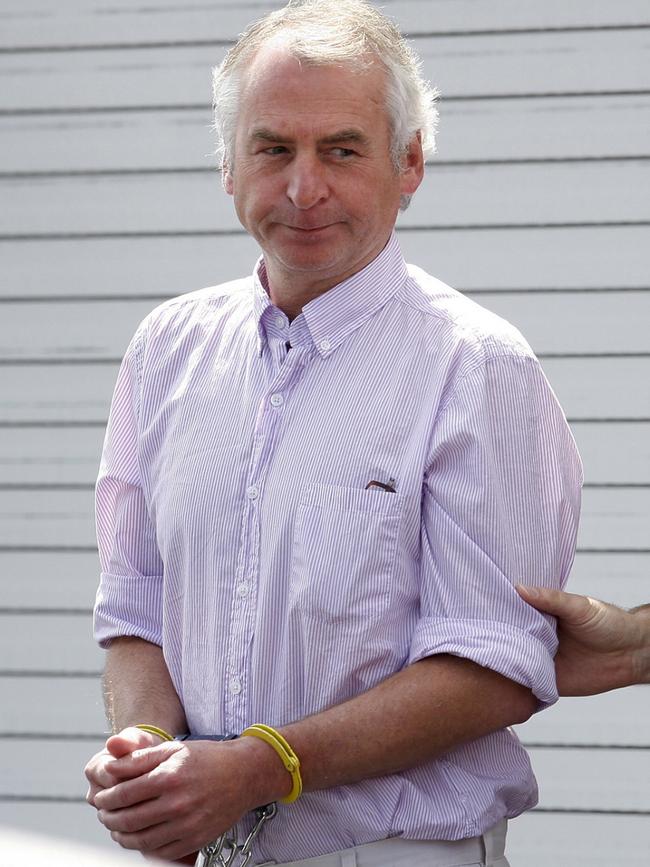

PAUL PETERS

Would-be extortionist Paul Douglas Peters shocked Australia and the world when he fixed what turned out to be a fake bomb around the neck of Sydney schoolgirl Madeleine Pulver.

A chilling ransom note warned that the device was booby-trapped and involved “powerful new technology plastic explosives”.

But it was another detail in the extortion note that would be Peters’ undoing — allowing police to identify him and track him to the US.

True Crime Australia: Will these clues solve 30-year cold case mystery

Blood trail leads to body: Daniel Morcombe dad’s first brush with murder

Peters, who spent time in both countries and had a home on the NSW Central Coast, sought contact via a newly-created email address — dirkstruan1840@gmail.com — to arrange the transfer of a “defined sum”.

He targeted Madeleine, who was 18 at the time, in her Mosman home as she studied for HSC trial exams. “Count to 200, I’ll be back … if you move I can see you, I’ll be right here,” he said, before leaving her.

The distraught teen would spend 10 hours in the device before it was eventually established there were no explosives and it was removed.

Before Peters could be identified as a suspect he had headed to the US.

But police were able to trace three logins on the Gmail account to Kincumber Library and an Avoca video store and from that obtained CCTV footage and a car registration — enough to identify the culprit.

He was arrested in Louisville, Kentucky, extradited, and in November 2012 jailed for at least 10 years.

The court head Peter’s life had unravelled before the crime, with a marriage breakdown, career problems and issues with his mental health.

He told a psychiatrist that he had to find “an ingenious way to trap myself” because he was drinking heavily and knew he needed help.

“I had to catch myself out,” he said. “I had to lay evidence along the way to trap myself.”

But sentencing judge Peter Zahra said there were “matters which point against the suggestion that the offender has given a reliable account” of his thinking at the time, and added: “It was a deliberate act of extortion.”

Last year Madeleine was given a bravery award along with Constable Karen Lowden who was with her during her ordeal when it was still thought the bomb was real.

“I am so pleased that Karen and all the people involved from the NSW Police Force are being recognised because they were truly extraordinary with the support they gave me and my family on the night,” Ms Pulver said.

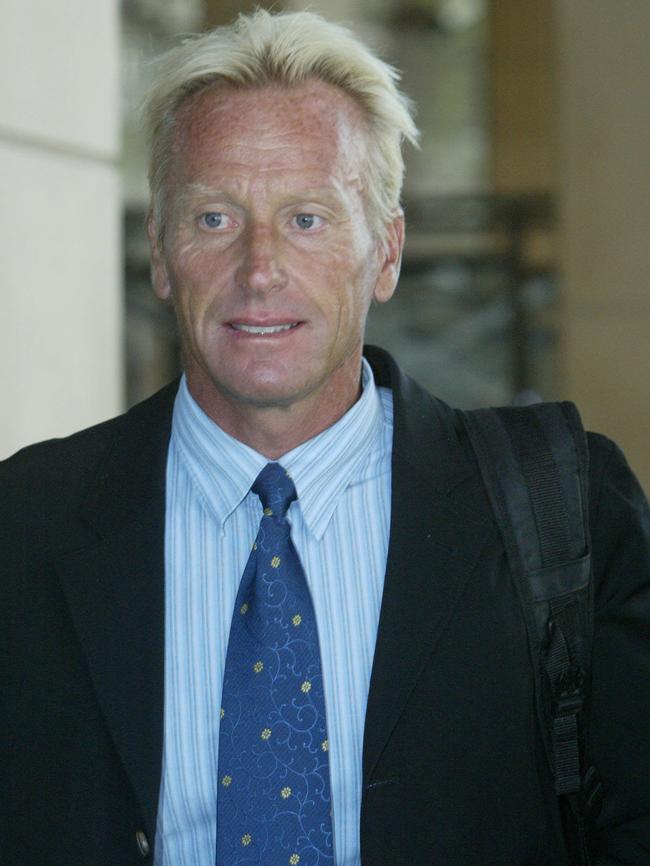

GAVIN HOPPER

While Peters was brought down by the detail in his extortion note, Gavin Maxwell Hopper came unstuck over the content of a very different type of letter.

Hopper was a high-profile tennis coach when he faced trial in 2004 accused over a four-year sexual relationship with a schoolgirl while he was a sports teacher at Melbourne’s Wesley College.

The prosecution alleged that the former student was just 14 when Hopper, who was married and twice her age, began his relationship with her in 1985.

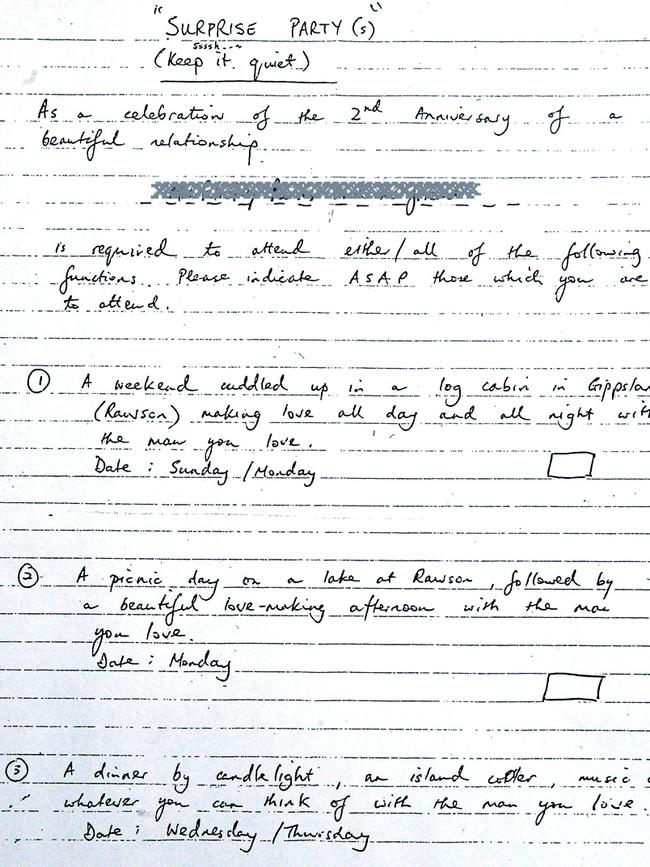

As part of the case the prosecution put forward what it believed was compelling evidence — a love letter it said Hopper had written to the schoolgirl in 1987.

The letter, titled “Surprise Party”, offered the recipient four options to celebrate the second anniversary of a “beautiful relationship”: A weekend cuddled up in a log cabin; a picnic day with an afternoon of “beautiful love-making’’; dinner by candlelight with an “island cooler”, or “none of the above because you are p---ing off the man you love’’.

Hopper told the court it was a letter for his wife, not the then schoolgirl, and marked their second wedding anniversary in 1981.

But then came the crunch.

Prosecutor Andrew Tinney was able to show the court the letter could not have been written until at least 1985, the year the Island Cooler was introduced to Australia.

Challenged over his evidence, Hooper, who always maintained his innocence, couldn’t explain a reference to the drink he had said was a favourite of his wife four years before it was launched. “I can’t shed any light on that,’’ he told the court.

In his closing address to the jury, Mr Tinney said that, with his attempt to explain the letter away, Hooper had “laid a trap for himself, a problem of his own making entirely: the Island Cooler trap”.

The jury found him guilty of three counts of indecent assault and six of gross indecency, resulting in a jail term of three and a half years, with a non-parole period of 27 months.

MARK RUST

In 2001, a recording of a call to 000 would put South Australian police on the path to solving two murders — but it was not the content of the call that provided the vital breakthrough, it was the caller’s voice.

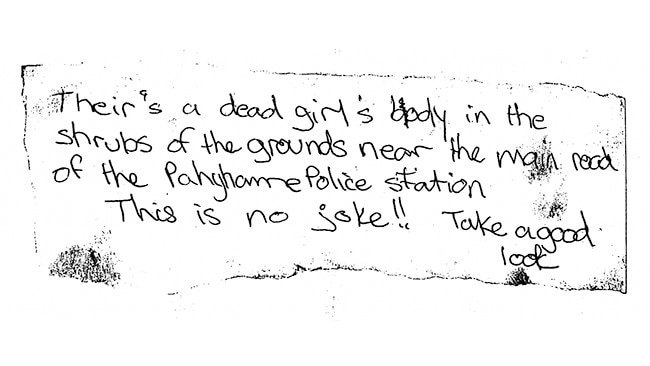

The 1999 murder of missing Croatian immigrant Maya Jakic was only discovered after a note was left on a police car at the rear of the Norwood police station on the night of Saturday, April 17.

It was the third attempt by an unknown man to direct emergency services to the body, which was hidden in bushes at the former Payneham police patrol base on Payneham Rd.

Five days earlier — the day Maya died — a man had phoned 000 to report people with flashlights around the “old Payneham police station”. The caller made a 000 call to the ambulance service the same day, but her body wasn’t found.

Requests for the “reluctant witness” to come forward failed, and two years later, with the case still unsolved, police turned to the internet, posting a recording of the 000 calls on the CrimeStoppers website.

Finally the information they needed came through — a caller to CrimeStoppers had recognised the voice, it was Mark Errin Rust.

FOLLOW: True Crime Australia on Facebook and Twitter

Checks revealed Rust had an extensive criminal history for sex offences and was in custody at Port Augusta Prison on remand for rape.

His handwriting matched that on the note left in the days after Maya’s murder.

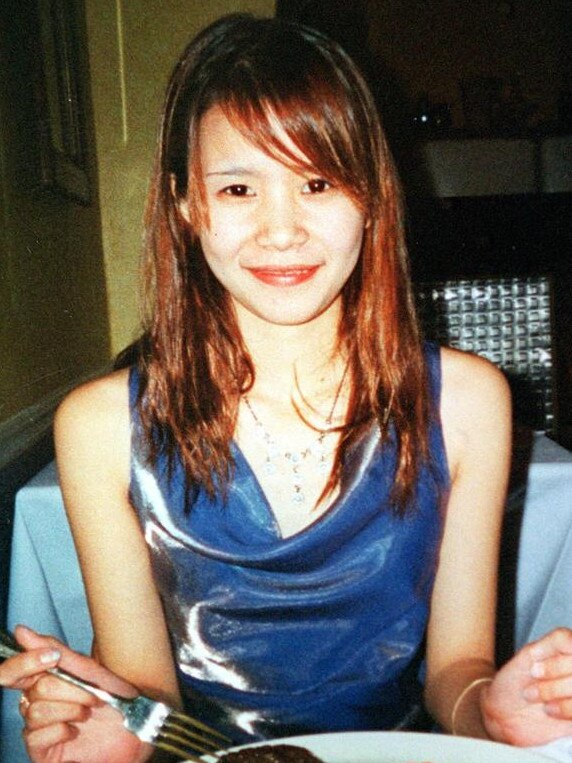

But it was only when detectives went to interview Rust in jail that they realised he was linked to another missing woman — there in his cell was an electronic organiser belonging to 18-year-old Japanese exchange student Megumi Suzuki.

Rust would soon admit to murdering both women, saying he killed Megumi on August 3, 2001, and dumped her body in a rubbish bin.

It would take nine days of painstaking searching at Wingfield dump to recover her remains.

But why did Rust even make the triple-0 calls that would eventually see him caught and jailed for life without parole?

In his book City of Evil, crime reporter Sean Fewster notes that Rust had a history of exposing himself to women and enjoyed their horrified reaction. But when he exposed himself to Maya in the moments before he killed her she just scoffed.

“Eager for sick gratification, he wanted the body to be found. Maya had not given him the horrified reaction he wanted, so perhaps the police would,” he writes.

Originally published as How three very different crims gave themselves away