Lesbian prostitute’s chilling confession in transvestite truck driver killing

No newspaper editor alive could resist a headline like ‘Lesbian Prostitutes Decapitate and Dismember Transvestite Pro-wrestling Truck Driver’. Beneath it all, however, the tale is even sadder than it is twisted.

Book extract

Don't miss out on the headlines from Book extract. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THEY call Adelaide the city of churches. But churches have graveyards full of skeletons. Read an extract from Sean Fewster’s book about Adelaide’s bizarre and murderous underbelly.

***

A Remorseless Betrayal: Casagrande and McGuinness

She was used to the pain of heroin withdrawal, that was nothing new. She’d grappled with the ravenous, gnawing drug hunger most of her life. This unfamiliar pain was unbearable. It was the sting of conscience, deep in her soul, and it refused to die down. It was Remembrance Day 2001, and Donna Lee Casagrande could no longer forget the sins she had committed.

Distressed and dishevelled, the junkie staggered into a police station in Redfern, New South Wales, and said she wanted to talk about a murder. Homicide detectives Robert Allison and Malcolm Lanyon led the blonde prostitute into an interview room and started its recorders. For more than an hour they listened as Casagrande spoke — alternately hysterical and chillingly calm — of slapping, torturing, smothering and stabbing a man to death.

The victim, Casagrande said, was a truck-driving pro-wrestler transvestite. Her accomplice was her lesbian lover and fellow prostitute. Remorse crept into her tone as she spoke of the victim’s immense weight; his corpse was too heavy, she explained, to load into his own four-wheel drive for disposal. And so the women had hacked the cadaver to pieces, de-fleshed each segment and buried the body fat in the victim’s beloved strawberry patch.

Loading the torso pieces into a car, the lovers dumped them at several different locations, pausing only to drop the cross-dresser’s head and arms in a rubbish bin and set them on fire. Having finished her sickening tale, Casagrande glared hungrily at the detectives. ‘All I want is my methadone,’ she said.

Though her confession had been made in New South Wales, the Detectives Allison and Lanyon were in no doubt Casagrande could only have committed such a heinous killing in Adelaide.

The life and death of John ‘Joanne’ Lillecrapp was, on the surface, bizarre and surreal — perfect tabloid fodder. No newspaper editor alive could resist a headline like ‘Lesbian Prostitutes Decapitate and Dismember Transvestite Pro-wrestling Truck Driver’. Beneath it all, however, the tale is even sadder than it is twisted. The undoubtedly horrific, inexcusable crime centred on one lonely man’s desire for friendship and acceptance.

In 1993, Lillecrapp moved into a house on Norton St, Angle Park, a suburb west of Adelaide. Like the western suburbs of Melbourne, it is an area that has long been home to Asian families and refugees from African nations. Violence is common, as is the death of young people in high-speed car accidents. ‘It’s best to keep to yourself around here,’ one resident said in 2001. ‘You keep out of trouble that way.’

Initially the locals called him ‘Tex’ because he wore large cowboy hats. Soon they got to see the woman behind the man — Lillecrapp had taken up cross-dressing two years before his arrival. One would think that he would have experienced enormous difficulties with his neighbours, but nothing could be further from the truth. He felt most comfortable when surrounded by his peers at the Parks Community Centre, just a few kilometres from his home. He considered them part of his extended family and volunteered many hours of his time driving the centre’s free bus service.

The African, Vietnamese and Indian communities looked to him for advice, help and support. He entertained them by taking part in professional wrestling bouts, playing both the hero and villain for the crowd’s benefit. Above all else, he insisted everyone call him Joanne.

‘He wasn’t your average bloke,’ Lillecrapp’s brother, Ron, conceded in 2003, ‘but he helped the community and he was a worthwhile member of the community. If anyone needed help, he would be there … The people at the Parks Community Centre thought the world of him … he found a place to belong there, something that was missing from other areas and times in his life. And while I wasn’t always close to John, if something were to happen I would have been there for him — that’s what brothers are for.’

A photograph of Lillecrapp taken on the night of his brother’s 1994 wedding sums the man up well. His dark wig and make-up are immaculately applied, his legs are swathed in stockings and his wrists and neck adorned with simple gold jewellery. In a plain white top, dark green miniskirt, stiletto heels and colourful jacket, Joanne Lillecrapp is the sort of 50-year-old woman one would pass in the street without a second glance.

But looking the part and being tacitly accepted by his neighbours was not enough. Lillecrapp felt his life was one of solitude, and he went further and further afield seeking what he felt would be true acceptance — the understanding of those like him, who shared his outlook and beliefs. During a trip to Sydney in 1996, he met Casagrande.

Born in Addington Hospital, New South Wales, in 1970, Casagrande was the youngest of nine children. Her father was a foreman at a sheet metal factory; her mother worked until she lost a hand in an industrial accident and moved to home duties full-time. In reports later tendered before the Supreme Court Casagrande claimed she was repeatedly abused — first by her father, then by the men for whom she worked as a prostitute.

She came to the sex industry after leaving school in Year 9 and moving unsuccessfully through jobs as a waitress, process worker and factory hand. Two abusive marriages brought forth two children — son Joshua and daughter Talia — who remained with their fathers. One of those men, she often claimed, would beat her senseless with a baseball bat and kick her in the head. Drug addiction and abuse was the defining factor of her life, ruining any chance of stability and taking a vicious toll on her long-term health. In particular, Casagrande struggled with heart valve problems and seizures.

Big-hearted, generous and full of empathy for a fellow ‘lost soul’, Lillecrapp opened his home to Casagrande, vowing to aid her rehabilitation. It was a decision that did not sit well with his family — especially when, during a visit with Ron and his wife, Lindsay, Casagrande retired to their driveway to shoot up heroin. ‘That was Joanne’s downfall, after that,’ Lindsay said in 2003. ‘We were worried about him, but he wanted to live his life the way he did. We tried to advise him but he was a man of 50 — you can’t tell anyone of that age how to live their life.’

Ron said his ‘slightly naive’ brother truly believed he could help Casagrande kick her habits. ‘He was a cross-dresser, that was the lifestyle he chose and that was his prerogative,’ he said. ‘He was a big sort of a bloke but he was a sucker, he was gullible. He was lonely and eager to befriend just about anyone. He wanted to help Casagrande — that’s what he was like. He probably went about it the wrong way but, if that’s the case, I don’t know what the right way is.’

Much later, Casagrande introduced her would-be benefactor to her lesbian lover — Nicole Therese Courcier McGuinness. The women had been in a relationship for three years — Casagrande would travel between McGuinness’s various residences and Lillecrapp’s home as her finances allowed. The couple had similarly unfortunate backgrounds.

McGuinness’s father left her family when she was three, exposing her to a stepfather who routinely abused her mother.

McGuinness herself fell victim to rape at the age of 15. She spent her life, according to defence lawyers, ‘either witnessing violence or being a victim of violence’. She turned to drugs, they explained, to ‘blot out the past and the present’.

Lindsay said the duo took advantage of her brother-in-law. ‘They seduced him into believing he had friends and that people accepted him and wanted to be around him. We thought it would end in theft, that they’d rip him off — but we never dreamed it would end like it did. We thought we could see what was coming and we knew it was going to be terrible, but not to the extent it was.’

For a time, the trio lived together in Lillecrapp’s home. He set up a bank account for the women, keeping the PIN a secret. That way, he reasoned, Casagrande’s and McGuinness’s spending would be vetted by him, ensuring they could not get money for drugs. It was a simplistic, overly optimistic plan that was doomed to failure from the outset.

Lillecrapp had no experience with addiction, no concept of how cunning a junkie could become to satisfy their need for drugs. His possessions and belongings began to go missing; McGuinness and Casagrande seemed to have drugs in their room more and more often.

On their visits to his family, the women became threatening and began to demand money. For Ron and Lindsay, it was the final straw.

‘He was vulnerable, and she poisoned his mind,’ Ron said of Casagrande. ‘She also stole a lot of things from him, including a video camera. They said they would trash our place if we didn’t give them money. The history, from then on, I do not know about because we could not allow this to happen in our home, so we had to distance ourselves from him.’

Little is known of the final 18 months of Lillecrapp’s life.

He continued to drive trucks, volunteer for bus runs and wear dresses. He remained a regular sight around the Parks and checked in sporadically with his community-centre friends. Neighbours remember him working in his garden, and that his strawberry patch was a point of pride. Unless he was actively volunteering, however, Lillecrapp kept to himself and spent his time at home with Casagrande and McGuinness. Occasionally, rumours would surface that he was ‘pimping out’ his houseguests, forcing them back into prostitution to pay their way. Such claims always lacked the facts to support them. In truth, the women would travel between Adelaide and Sydney as they could afford, most often to see Casagrande’s children.

In November 2001, South Australian police received word that Lillecrapp was missing. Days later, they became aware Casagrande and McGuinness were gone as well. Concerns began to mount, and came to a head on 9 November, when an anonymous caller told triple-zero operators that ‘someone might be dead’ at the Norton St house. Forensics investigators and Major Crime Investigations Branch detectives moved quickly. What they discovered was among the grisliest, most gruesome finds in the state’s criminal history. Human remains had been buried in the strawberry patch but they were not whole. Officers found body fat, flesh and chunks of torso between and beneath the fruit. The deceased had been butchered, either before or after he was killed, and the offal left behind.

They are either cold, callous and brutal, or flying high as a kite on drugs

On 13 November, police confirmed the remains belonged to Lillecrapp. They continued the search for the rest of his body, and appealed for help finding Casagrande and McGuinness. They spoke of extending the search interstate, and of working with police in Sydney to locate ‘persons of interest’. What they were not prepared to reveal, however, was that Casagrande had already turned herself in at Redfern and confessed.

Casagrande’s arrest was announced on 15 November, and she was extradited to Adelaide by order of the Parramatta Court. A newspaper photographer caught a brief glimpse of the alleged killer as she was taken away from Adelaide Airport on 17 November. Looking drawn and weak, dressed in a tank top and striped tracksuit pants, Casagrande cowered behind a police officer’s jacket and wept. She was held in the City Watch House until 19 November, when she made her first appearance in the Adelaide Magistrates Court. She had been, by this time, given new clothes to wear — jeans, running shoes and a long jacket. She cast an unsteady eye toward the media cameramen who filmed her arrival, and had to be physically led into the courtroom by a sheriff’s officer. She was remanded in custody.

One day later, McGuinness was arrested. Police released few details of her apprehension and the public found out little more when she appeared in court on 21 November. At the request of prosecutors, Magistrate Alfio Grasso slapped suppression orders on the images of both defendants — banning the media from showing their faces to a confused public. At the time, no one outside the investigating team had any clue why Lillecrapp had been murdered — including his family.

‘I can’t assume the remains are him,’ Ron told reporters in 2001. ‘Obviously, I hope he is still alive. The thing that really hurts me is how someone can do it. They are either cold, callous and brutal, or flying high as a kite on drugs.’

His hopes were dashed on 30 November of that year.

Lillecrapp’s head and arms were found, burned almost beyond recognition, in a drum at Wingfield dump. Not only had he been butchered, he had been dismembered and decapitated.

Coincidentally, the macabre discovery was made just 200 metres away from where teams were excavating for the remains of another murder victim — Japanese schoolgirl Megumi Suzuki, who was killed by escalating rapist Mark Errin Rust. It was a hideous happenstance that further reinforced Adelaide’s reputation as the nexus of Australia’s bizarrely malicious crime.

The drum had been discovered by an employee of a concreting and restoration business. The man would never be the same again. ‘I wished it had never been found there,’ he blanched, visibly distressed. ‘We just found it there, it had nothing to do with us. We just called the police and they took it away.’

Casagrande’s and McGuinness’s appearances in court became sporadic. They did not face the Supreme Court until October 2002, at which time both pleaded not guilty to murder. Six months later — in April 2003 — they fronted the court once more. This time McGuinness announced she was changing her plea, and would confess to murdering Lillecrapp. Casagrande continued to protest her innocence.

On 3 June 2003, a near-hysterical Casagrande was brought before Justice John Perry. She began weeping the moment she entered the courtroom, and mouthed messages to friends and supporters sitting in the public gallery. Her composure, however, returned instantly when she was addressed by Justice Perry. The renowned and much-beloved judge and educator, who was nearing mandatory retirement, asked the woman how she intended to plead to the charge against her.

‘Not guilty to murder,’ Casagrande replied, wiping away her tears, ‘but guilty to manslaughter.’

Craig Caldicott, for Casagrande, told the court the months of silence had been put to good use. He said that, by the next hearing date, he would have psychiatric reports about his client. Having worked closely with prosecutors, he would also be in a position to tender a statement of agreed facts — the basis upon which Casagrande was to be sentenced.

Justice Perry was appreciative. ‘I’m still looking for a clear understanding of the motive and circumstances around the killing,’ he said, echoing the thoughts of many in the public gallery. ‘I also want to know what part each of them — Casagrande and McGuinness — played. Quite often that’s what these things come down to — which part each of them played, and what they say about the role the other played. I intend to deal with both of them strictly together and hear submissions on the same day.’

That scheduled hearing date — 1 July 2003 — would see an end to the mystery surrounding Joanne Lillecrapp’s death.

In a rare move for a South Australian judge, Justice Perry dispensed with the secrecy so beloved by his brothers on the bench and released Casagrande’s court file to the media.

Within the pages of documentation lay a complete transcript of the Redfern interview — and the details it provided were beyond belief. Not only did she detail every moment of the murder, Casagrande also painted a picture of Lillecrapp — whom she always referred to as ‘Joanne’ or ‘her’ — quite unlike that given by his family, friends and the police.

‘I’ve been going to Joanne’s on and off for years, and she’s been coming up to my family’s place for years,’ Casagrande had told the homicide detectives on 11 November. ‘Joanne dobs people into Social Security … she’s very spiteful. The last summer I was there, I stole her camera and, when I got down there this time, she asked me where it was. I told her that I sold it for heroin in Melbourne. I told her I would get her a new one, and I wanted to leave that day but she locked me in the house and I couldn’t get out.’

Later that day, she said, her lover made a discovery. ‘Nicole went into Joanne’s bedroom and found a piece of paper from the Footscray CIB in Melbourne. That’s where I had sold the camera at. She showed it to me.’ The women were convinced Lillecrapp intended to turn them over to interstate police because of the camera theft. Knowing he still had $600 of Casagrande’s money in the account he had created for them, the women hatched a plot to get it back and then leave Adelaide for good.

‘Nicole cooked Joanne dinner and she put a couple of Rivotril in her dinner … they’re epilepsy tablets,’ she said. The highly potent anti-convulsant has powerful muscle-relaxing properties, but also induces drowsiness and impairs the memory. The lovers felt it to be their best tool against someone larger, stronger and healthier than the two of them put together.

‘I went out to Joanne and said “You haven’t changed at all, you’re still the same”,’ Casagrande continued. ‘I said “I’ll buy you a new camera” and Nicole kept waving the paper in her face and saying “Well, what’s this, what’s this?” And Joanne said yes, she was going to ring up (the police) but she hadn’t.’

Give us the f**king money, Joanne, or you’re going to die today

The argument escalated. ‘I asked Joanne for my money out of the bank, which I was saving up for my son,’ Casagrande said. ‘Nicole went into the kitchen and got a stay-sharp blade — you know the ones, the ones with the white handles. She came back into the lounge room and said to Joanne “Just give us our money, and we’ll go”.’

Casagrande insisted the knife was for Nicole’s own protection — Lillecrapp was far bigger and stronger than the women. She claimed they feared he would attack them. ‘I don’t know what happened — Joanne must have thought it was a bluff or something — but it didn’t work. So it got a bit more heavy and I flipped out, I said “I just want my money, my son’s money, and I’ll go”. I kept telling her I’d buy her another camera.’

Tempers flared out of control and things turned deadly. Casagrande pushed the weakened Lillecrapp onto the lounge room floor. ‘I was holding her saying “Why, why, why?”’ she said. ‘I just straddled her. Nicole was in the background saying “You lying c**t”, and I had my knees on Joanne’s arms.’

Unwilling to sit on the sidelines any longer, McGuinness attacked Lillecrapp. ‘She had the knife,’ Casagrande insisted. ‘Nicole sat up on top of her and started punching her. She still had the knife in her hand and she was saying to her “Just give us the money and we’ll go, you know how much it means to Donna’s son”. She said to her “Give us the f**king money, Joanne, or you’re going to die today. If you don’t give it to us, and let us go, I’m going to kill you”. And Joanna wouldn’t — she still wouldn’t give it back. I don’t think she ever had any intention of giving us our money back in the first place.’

Lillecrapp began to fight back. When he couldn’t shift McGuinness with the force of his bulk alone he panicked and began to scream. Casagrande punched him in the face, breaking his nose. ‘We were yelling and screaming,’ she said. ‘And then, because she was screaming, Nicole put a pillow over her face and told her to shut up,’ Casagrande remembered. ‘She said, “Just give us the PIN and we’ll go get the money, I’ll go get the money, Donna can go get the money. Then we’ll leave, and everything will be all right”.’

Lillecrapp still would not cooperate and so McGuinness threw the pillow aside and began to slap him. Keeping the knife tight in her other hand, she struck repeatedly with her palm, knuckles and fingernails, cutting and scratching her victim’s face. ‘After a little bit longer of being slapped around a bit, Joanne gave us the number,’ Casagrande said.

Leaving McGuinness and Lillecrapp behind, the junkie took her benefactor’s four-wheel drive to a pub on Hanson Rd, Arndale. Hands shaking, she tried the PIN. It didn’t work. She tried it several times, her anger increasing, before giving up and returning to Norton St. ‘I was pissed off,’ she admitted. ‘When I got back to the house, Nicole was still straddling Joanne, with the knife in her hand and the pillow over her face. And Joanne had four stab wounds in her, right in her temple. They weren’t deep.’

McGuinness was infuriated, she said, enraged that they had been tricked — and she was no longer prepared to play games. ‘Nicole said, “See? I told you, you stupid bitch, that you weren’t going to give Donna the right number! I knew it, I knew she was going to come back and tell me it wasn’t the right number! I knew you were lying, I knew you wouldn’t give us the PIN, money means more to you than anything!” Nicole was holding the knife up against her throat and Joanne tried to get up.’

Casagrande paused in her retelling, swallowed, and put her head in her hands. Her words began to blur together.

‘Then just bang, she stabbed Joanne straight through the heart,’ she babbled. ‘Nicole put the knife straight through her chest, one through her heart, and four times in her stomach. There was blood coming out of Joanne’s mouth. Joanne reached out and grabbed my hand. I held onto it. And then it was too late.’

One of the detectives asked if Casagrande had tried to stop her lover’s murderous actions. She admitted she had not. ‘I was angry,’ she said, ‘and I was scared. Then Nicole looked at me, smiled and said, “I can’t believe that money can mean more to someone than their own life”.’

Casagrande said she began to panic, even though McGuinness ‘was pretty calm, actually’. Together they dragged Lillecrapp’s body into the bathroom. It was Casagrande’s idea.

‘The blood wouldn’t go,’ she said. ‘There were pools of blood everywhere. I washed a bit off but I just … just kept …’ Her retelling broke down. ‘Blood and all,’ she muttered. ‘Trails of blood everywhere.’

Composing herself, she continued the story. They had wrapped Lillecrapp’s body in a blanket and dragged him out into the backyard and onto the grass. His weight, combined with their poor health and addiction-ravaged muscles, made it impossible to lift Lillecrapp. ‘I tried to put her into the four-wheel drive but she was too heavy. We had to get some ropes, tie her up and try to pull her over the grass to the car. And she still wouldn’t move! There was no way of getting her into the car, she was too heavy! So Nicole went and got the tool box, because there was an axe inside it, and a hacksaw.’

The stomach-turning series of events that followed would forever immortalise the names of McGuinness — who was still carrying the knife — and Casagrande in Adelaide’s rogues’ gallery of hideous criminals. ‘Nicole kneeled down next to them and looked at the hacksaw, but she said it was too blunt. So then she cut through Joanne’s skin with the stay-sharp knife. Then she picked up the axe and chopped off Joanne’s head with it. We put that in a bucket.’

The detectives stopped Casagrande, asking whose idea it was to dismember Lillecrapp. ‘Mine,’ she said, almost too softly for the tape to record. ‘Then Nicole said “let me do it”, because I was crying too much.’

Casagrande appeared, to the detectives, to be completely disconnected from reality. She was lost in her story, but spoke as if someone else had perpetrated the disgusting act of human butchery. ‘We still couldn’t pick Joanne up, she was too big,’ she went on. ‘So then both of her arms had to come off. And after that she was still too heavy, and so big. We tried to lift her and, when that didn’t work, both her legs came off, at the groin, so it was just a torso left. The worst bit was the torso … she was so fat. Anyway, I got the stay-sharp knife and cut all the fat off Joanne’s stomach, and we wrapped her back in the blanket.’

Their bloody work complete, their composure returned, the women became calculating. McGuinness and Casagrande first buried Lillecrapp’s stomach and body fat in his prized strawberry patch. Then they wrapped his arms and legs in garbage bags and put them, with the head in a bucket and the blanket-shrouded torso, in the four-wheel drive. They headed to a lake ‘about 100 kilometres’ from the city. ‘Nicole was saying something about putting something heavy on Joanne and putting her in the water, so she wouldn’t float,’ she explained. The plan went awry when they discovered the lake was a popular fishing spot, already bustling with activity.

Casagrande said they drove into the Adelaide Hills and buried the legs and knife near the Mount Lofty Botanical Gardens. The detectives wanted to know why the women did not bury the body in one location. ‘It probably would have been easier,’ Casagrande replied, as if realising it for the first time, ‘but I thought that, if they found a torso, then maybe they wouldn’t know who it was.’

Once Lillecrapp’s torso had been safely dumped on a beach at Port Parham, the lovers made their way back to the city. ‘We went and bought some petrol and put that in the bucket with her head and arms,’ Casagrande said. ‘It was about 4 litres of petrol. Nicole took us to this factory at Wingfield, and she went inside. She put the bucket with the head in it in this incinerator, and the arms too, and Nicole was yelling out “Hurry up, hurry up before someone comes!” I ran over to the gate and threw her a lighter. She threw all the petrol in, and about twenty newspapers in there as well, and then lit it up.’ She shuddered. ‘I keep dreaming about it. Picking her head up by the hair, putting her head in the bucket.’

After that, Casagrande said, the couple ‘just drove home’.

‘I knew, straight away, we were going to get caught,’ she admitted wryly. ‘I knew it, and I couldn’t stop crying. Nicole gave me some pills so I could sleep. Then, early on the Thursday, we packed our stuff in the four-wheel drive.’ Their getaway plan was foiled by, of all things, a minor car accident.

They decided to dump the vehicle and hitchhike their way to Sydney. Though she had no way of knowing for sure that the police were looking for her, Casagrande was pessimistic enough to believe capture was inevitable and a confession might help her score her next fix. She made a triple-zero phone call from a payphone and tried to convince the call centre to swap her confession for drugs. When that failed, she went to the police herself. And, with her sins revealed, she was not happy to learn methadone was not part of the deal.

‘I wanted to go get my methadone, I should have gone and got my methadone but I’ve been trying to build up the courage to do this,’ she screamed at the detectives as her addiction savaged her body. ‘This is bullshit, this is f**king bullshit! You f**king promised me methadone! I don’t have to f**king do this! I’m trying to do the right thing — I came in here to tell the truth, not get f**ked around! I’ve got two kids that I’ll frigging never probably see again after this, and all I want is my methadone!’

The truth had, at long last, been revealed. It came as cold comfort to Ron and Lindsay Lillecrapp. Under South Australian law, victims of crime are given an opportunity, during sentencing submissions, to tell both the court and the criminal how they have been affected by the offences in a victim impact statement. Ron and Lindsay had expected to begin the healing process on 1 July 2003 by delivering their victim impact statements and hearing the sentencing submissions for both accused. Only one of those things was to happen.

David Stokes, for McGuinness, informed the court he had only just received the results of his client’s psychological testing. She also had yet to sign the all-important statement of agreed facts asked for by Justice Perry. ‘I’m not in a position to make submissions today for that reason,’ Mr Stokes said.

Craig Caldicott, for Casagrande, also had concerns. ‘In respect of the victim impact statements, my client hasn’t had an opportunity to see them,’ he said. ‘I was handed them as I entered the courtroom this morning. There are portions of the statements which express opinions from the person which are clearly at odds with the plea that has been entered by Ms Casagrande.’

Mr Caldicott is a renowned and highly regarded member of the bar in South Australia. Until that day, however, no one knew he had a gift for understatement. His comment, as it turned out, was actually more of a warning to which Justice Perry should have given due consideration. He did not, however, and ordered the statements be read.

Casagrande and McGuinness sat, close together and silent, as Lindsay Lillecrapp read her statement to the court.

Overwhelmed with emotion, she broke down and cried after just a few sentences. ‘Being here today is something I never thought I would have to face in my lifetime,’ she continued, ‘but I feel compelled to speak up today. Over the past 18 months I have experienced a multitude of emotions, from great sadness to absolute horror. For a member of your family to die in such an unspeakable manner goes beyond anybody’s reasoning. I frequently think about Joanne’s last thoughts, the terror and absolute betrayal of these two women and the heinous crime they inflicted on Joanne that terrible night.’

Gathering her strength, Lindsay looked up from her notes and glared at the killers. Casagrande began to shake. McGuinness placed a consoling hand on her lover’s knee.

‘No human being deserves that kind of death — to be drugged, wounded, killed and then dismembered by two women committing this crime for money,’ Lindsay went on. ‘We, the family, have listened to the facts and the horrors of this crime. We have remained silent. We have even been glared at, had faces pulled at us by the defendants. I myself have never seen one sign of remorse from these two women, and it chills me to the bone.’

Casagrande was fading, ruined by guilt, accusations and heroin withdrawal. She would have much more to endure before the hearing was over. ‘Donna presents herself as the less guilty one because she did not stab Joanne,’ Lindsay said, staring unblinkingly at Casagrande. ‘She participated in drugging Joanne, then she dismembered the body and helped hide the body parts. Her part in this hideous crime deserves to be recognised as horrific, and should be dealt with severely.

‘These two women have turned my life, and that of Joanne’s family, upside down. The grief and loss they have caused can never be forgiven. The only thing that can help myself and Joanne’s family today is that justice is done, and these two women are punished and imprisoned for a very, very long time.’

Ron Lillecrapp locked eyes with his wife briefly, as they passed one another in the gallery. He strode to the podium in a way that suggested power beneath the pain. A tall, strong-looking man — not as large as his brother, but stocky nonetheless — his body language practically shouted that he would not be broken by Casagrande and McGuinness. Twice had he lost his brother to these women — once when the family ruptured, and again when Joanne was murdered. No more would he bottle up his pain. Unlike his wife’s measured tones, Ron spoke with venom and volume, and his chin jutted defiantly at the killers as he verbally tore them apart.

‘I first met Donna Casagrande in early 1996,’ he began. ‘John, my brother, had brought her to our house for tea. She abused that privilege by shooting up drugs in the driveway in the presence of my wife and parents.’

Casagrande flushed red, and would be silent no longer. ‘I did not,’ she shrieked hysterically, stunning those in the courtroom.

‘She poisoned John’s mind,’ Ron continued, refusing to be interrupted. ‘After that night they made demanding threats to us. They said they would trash the place if we didn’t give them money.’

‘You liar, you liar,’ Casagrande howled. ‘You’re a bloody liar!’

‘You know I’m not,’ Ron shot back, glowering.

‘That is a plain lie,’ Casagrande yelled again. ‘You said you hated him!’

Mr Caldicott’s fears had come to pass. Justice Perry moved quickly to regain control of his courtroom. ‘I’ll have to put you out of court if you say any more,’ he told Casagrande, firmly but not unkindly. ‘You just have to sit.’

Casagrande did. McGuinness was waiting for her. She pulled her lover into her arms, lowered her head onto her shoulder and began stroking her hair. Her murderous eyes remained fixed on Ron Lillecrapp, as if daring him to say another word against the woman she adored.

Ron did that, and more. ‘John was naive and gullible and they played on that as much as they could until a time when he said “enough is enough”,’ he growled. ‘It was okay for them to steal from him but, when he said “no” they killed him. Butchered him grotesquely. That is, in my opinion, premeditated. I see you both equally guilty of the murder and I feel that at no time in these proceedings have I seen any remorse expressed.’

He said they deserved more of a punishment than any court could impose — for stealing not only Joanne’s possessions and links to his family, but also his remaining years.

‘He didn’t have you, his family, did he?’ McGuinness spat.

‘I suggest you have no feelings, considering you could butcher a person,’ Ron replied darkly. ‘I cannot imagine how anyone could mentally be able to commit that crime, let alone physically. He tried to help both you women get off drugs. He gave you the same credit he gave others in the community — his time and his energy to help you.’

Casagrande pushed away from McGuinness, rose to her feet and strained against the glass walls of the dock. ‘He sold me as a prostitute, that’s what he did,’ she screamed, bringing the old rumour back to life. ‘He sold my body, that’s what he did!’

Justice Perry had had enough. ‘Mr Caldicott, I’ll have to put your client out of court,’ he said, signalling for the sheriff’s officers to take her to the cells. ‘There is no way of maintaining the dignity of the court.’ Casagrande was removed, still crying and yelling at Ron Lillecrapp.

He took a deep breath and went on, now directing all his pain toward McGuinness. He answered her earlier accusation and admitted he had not always been close to his brother. ‘I feel angry and cheated,’ he said. ‘I will always have to wonder what our relationship as brothers might have eventuated into. I have lost a brother that I could turn to if I needed to.’ His voice broke. ‘I lost him long before you two murdered him,’ he said quietly.

‘Yes,’ McGuinness hissed.

Her contempt energised Ron. ‘You totally shafted him, you stole from him, you killed him and I am so angry for that it is very hard to express,’ he raged. ‘There’s a quote from the Bible — an eye for an eye. A lot of the time when I think about this, I feel it should be a life for a life!’

‘Do it,’ McGuinness yelled, standing up and leaning toward the glass. ‘Do it, do it!’

‘You’re both guilty of murder,’ Ron said, disgusted. ‘The worst kind — the kind that scares the whole community, not just my family. The whole population knows what you have done and what you’re capable of. They have been reminded that ruthless people like you still exist.’

He returned to his seat in the court, pale but unbroken. It was clear that, despite his best efforts, Casagrande’s hysteria had unnerved him. Lindsay clasped his hand tightly as he sat down, and acknowledged the sympathetic glances from those in the gallery. Justice Perry allowed Casagrande back into the court, then agreed to a short adjournment so that Mr Caldicott could speak with her.

‘I’ve been instructed to apply for an adjournment,’ Mr Caldicott told the court upon its resumption. ‘My client is having difficulty this morning.’ He asked all submissions be given on the same day — 17 July — given that he needed time to speak to a cardiologist about Casagrande’s ongoing heart valve problems. Justice Perry agreed, and remanded the duo into the custody of the Adelaide Women’s Prison at Northfield.

Ron Lillecrapp’s words had more effect on Casagrande than he realised. That night, prison officials were called to the killer’s cell — she had slashed both her wrists in a suicide attempt. Working quickly, officers and medical staff were able to save her life, and she was kept under close watch until her next court appearance on 17 July.

Mr Caldicott was quick to inform the court of his client’s suicide attempt. It was, he ventured, a sign of her true self. ‘She is extremely contrite and remorseful as to what has happened and what has occurred,’ he said. ‘I have been specifically instructed not to take issue with any of the victim impact statements that were read out on the last occasion. She clearly was remorseful, and has been through all of the period, and wanted me to express that to the court.’ He said sentencing Casagrande would be a difficult exercise.

‘She wasn’t the person that did the killing,’ he reminded Justice Perry. Were she to be sentenced on the basis she had assisted McGuinness in the murder, then she would have been sentenced incorrectly — a juicy point for an appeals court.

In response, Justice Perry said he felt Casagrande’s true crime was ‘unlawful and dangerous acts’ including drugging and restraining Lillecrapp, breaking his nose and being present when the killing took place. ‘There is a slight air of unreality about that,’ he said wearily. ‘It puts her close to the margin, doesn’t it, between manslaughter and murder.’

One couldn’t think of a poorer excuse to deliberately take a man’s life than to get a few hundred dollars out of a bank account

Mr Stokes, for McGuinness, took his turn at the bar table next. His client, he said, was suffering from rampant memory loss. His claim was supported by psychological evidence suggesting the memory loss was genuine given the murder was committed ‘in a haze of drugs’. ‘She doesn’t dispute the last part of this episode, when the stabbing occurred that resulted in death,’ he said, ‘because Casagrande remembers it. McGuinness says she can’t remember it, but she accepts it and accepts she intended to kill.’

He edged toward suggesting it was a spontaneous crime, but Justice Perry was not interested in hearing that. ‘It was spur of the moment, but that is to be considered against the victim being forced eventually to give the PIN,’ Justice Perry said. ‘When news breaks that the PIN is not right, the situation heats up and culminates in your client stabbing the victim in the heart. So although I have to accept that it wasn’t premeditated in the ordinary sense and was spur of the moment, it was the culmination of a relatively long period of restraining and assaulting the victim.’

Stephen Millsteed, prosecuting, argued there was little room for mercy. ‘This is a particularly serious example of murder,’ he said, ‘and there are four serious features about this case.’

The first was McGuinness’s admission she had a specific intent to kill Lillecrapp, the second was the victim’s defenceless state, the third was the motive for the crime.

‘In essence, McGuinness killed this man because she and Casagrande couldn’t get a few hundred dollars out of a bank account,’ he said. ‘One couldn’t think of a poorer excuse to deliberately take a man’s life than to get a few hundred dollars out of a bank account.’

The hideous aftermath of the killing, Mr Millsteed said, was the final factor: ‘The gruesome dismemberment of the body is relevant in two ways. First, it sheds some light — indeed, in my submission, a good deal of light — on the callous state of mind the women were harbouring at the time. Secondly, it’s an important feature when one has regard to the adverse effects that this crime has had on the victim’s family.’

Justice Perry pointed out the butchery was ‘logistical, not ritualistic … it was a combination of trying to get the body in the car and also trying to conceal the fact that a crime had been committed.’

Mr Millsteed agreed. ‘The mere fact they have taken a logistical decision to dismember this man’s body is, in itself, an aggravating circumstance.’ So, too, was Casagrande’s failure to prevent Lillecrapp’s death. He said her inaction placed her manslaughter charge ‘right on the cusp’ of murder.

‘The Crown accepts there was no intention, on her part, to cause death or grievous bodily harm to Mr Lillecrapp,’ he said. ‘But it’s quite clear she did not try and stop McGuinness from stabbing the victim.’

Justice Perry remanded the lovers in custody one last time. His task was clear, though working his way through the legal complexity of Casagrande’s involvement would require a little extra thought. Seven days were enough; the women were summoned back to the court on 24 July for sentencing.

Once they arrived, he did not mince words.

‘Both of you are the products of broken homes and had childhoods punctuated by violence and drug addiction,’ he said as the women huddled together, their arms around one another. ‘You both have spent substantial periods during your adult lives in jail.’

The effect on their psyches was evident. Casagrande, he said, had a ‘borderline personality disorder’ and depression that found expression in her suicide attempt; McGuinness shared her beloved’s disorder while also suffering from impulsivity.

‘This killing was preceded by an attempt to incapacitate the victim, who was rendered defenceless and then detained,’ he continued, relating the story of the PIN argument. ‘This killing was followed by the gruesome dismemberment of the body. Not only does this demonstrate the cold-blooded callousness of your conduct, but later it had a devastating effect on the victim’s family.’

In the gallery, Ron and Lindsay Lillecrapp held each other close.

‘McGuinness, you have conceded you had an intention to kill,’ he said. ‘Your plea, Casagrande, is advanced on the footing you are guilty of unlawful and dangerous conduct but that you did not have an intention to kill. Even so, you actively participated in the preliminaries to the killing. While present you did nothing to stop McGuinness from stabbing the victim, and you actively participated in the attempts to dispose of the body. For the purposes of sentencing, your crime must therefore be regarded as in that category of manslaughter which is close to murder.’

He jailed McGuinness for life and imposed an 18-year non-parole period. It would have been 24 years, he said, if not for her admission of guilt. Casagrande, he said, deserved a 12-year sentence, of which she had to serve a minimum of ten years.

Casagrande began to weep once more; unusually, McGuinness also started to cry. Their grief was palpable, overwhelming and difficult to watch. They were prised apart by sheriff’s officers and led, one by one, back to the cells.

That evening they began their long terms inside the women’s prison, where they remain to this day.

For Ron and Lindsay, the sentencing was the moment their healing began. ‘Today was the first time I noticed their remorse,’ Ron said outside court. ‘Crocodile tears tend to flow easily but today I think they were finally sorry. I get some small peace of mind from that. We can finally start to find closure.’

He was quite happy with the jail terms imposed.

‘They deserved what they got, and Justice Perry did the job right,’ he said. ‘It’s finally over, we finally have some closure and we can go forward now that justice is done.’

Lindsay said she hoped some future good could come from the case — particularly for others in her brother-in-law’s situation. ‘He wanted to be known as Joanne, to be accepted as Joanne, all his life,’ she said. ‘It’s a hard life, so just be very careful how you live it and who you choose to mix with. Just because you choose an alternative lifestyle doesn’t mean you have to be shunned and taken advantage of. We accepted it — it was hard, but we never shunned him for the way he lived his life — and other people need to be the same way.’

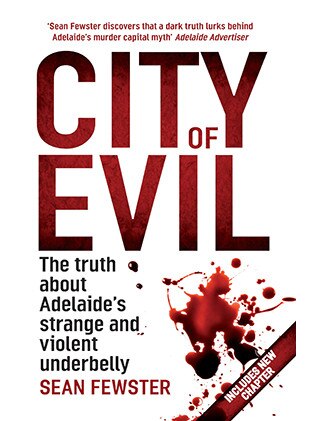

• City of Evil: the Truth about Adelaide’s Strange and Violent Crime by Sean Fewster is published by Hachette Australia, RRP $22.99, e-book $11.99)

• This extract was first published by The Advertiser in January 2014.

Originally published as Lesbian prostitute’s chilling confession in transvestite truck driver killing