Death on a dairy farm: The search for answers Kaye King’s children never got

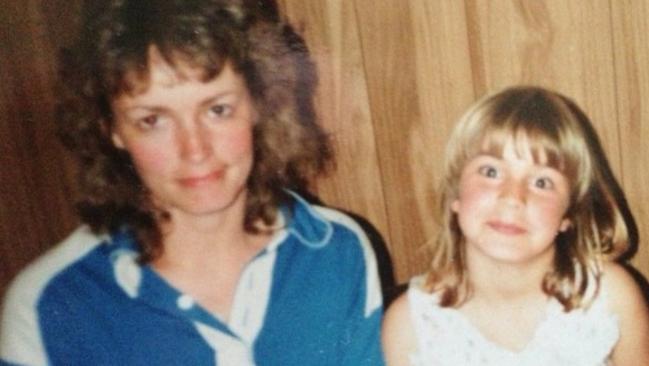

GRIEF flowed after Kaye King died in a dirty pit on her family farm. It was only later, when her children compared stories on exactly what happened that day, that clues came together to suggest foul play, possibly at the hands of their father.

Cold Cases

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cold Cases. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A JURY couldn’t make up its mind about Graeme King but his adult children have. Of the four, three shun their father because they believe he may have killed their mother.

That a second jury eventually acquitted King of murder hasn’t altered their view.

His oldest son has changed his surname so his children have no tie to a grandfather they will never meet and never mourn.

HOW SPORTS STAR SAW CARL WILLIAMS DUMP ESKY BODY AT BEACH

‘THE TEXAN’ WAS THE ONE-TIME UNDERWORLD GENERAL OF WATERSIDE

PAEDOPHILE REGINALD ISAACS PRIME SUSPECT IN UNSOLVED 1973 MURDER

It is 25 years this weekend since Kaye King’s second son, Peter, found her bruised body in a flooded pit on their dairy farm at Katandra near Shepparton.

He saw her gumboots first, the bright orange soles standing out — astonishingly clean despite deep mud on the track from the house.

Peter screamed to his father and younger brother John, who came running. They hauled Kaye from the pit and Peter attempted mouth-to-mouth resuscitation while his father watched.

The filthy water ran from her mouth but she was dead.

“She felt so cold,” Peter would say much later, reliving an ordeal that would give him nightmares and derail his life until his 30s.

“I’d never felt anyone so cold before.”

The ambulance arrived at 3.18pm and went through the motions but it was a job for the undertaker. And the coroner.

By the time local police — young uniformed constables — got there less than an hour later, neighbours had already started arriving.

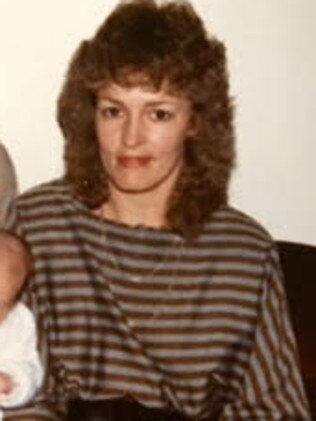

Kaye was a regular church goer, her husband a local football stalwart, and their children all played sport in the district.

It was natural to feel sorry for the big farmer and the three devastated children, Peter, John and Nicole.

The oldest, Jason, had recently started an apprenticeship in Melbourne and got home later. By then, half the district had turned up with food and sympathy. It’s the country way.

One constable thought King seemed too “visibly distressed” to say much but the farmer managed to say his wife must have stumbled — or been knocked over by cows — so that she fell into the “well”.

The freak accident scenario was repeated as each wave of visitors arrived and it soon acquired the patina of truth.

The first detective at the scene was Ken Mansell, a seasoned country cop who had grown up around farms. To him, the odds against an accidental drowning were huge.

In his long experience, while children might drown on farms, adults don’t unless they want to. And this didn’t look like suicide to him.

Mansell checked the body lying under hessian rugs next to the pit, a shallow “sump” in the middle of an old pig pen.

He saw two things clearly: the dead woman’s gumboots were clean, and she had a neat oval bruise on her forehead.

Mansell called for the police surgeon and the homicide squad.

He walked to the house, shoes sinking into the ankle-deep mud. No one noticed him, he would claim later, except the dead woman’s husband.

“He watched me like a hawk,” Mansell later claimed.

IGNORANT PEOPLE ARE WARPING THE ANIMAL WELFARE DEBATE

FRANKSTON ARREST COULD BE KEY TO CRACKING GRIMMER COLD CASE

A neighbour, Henry Wells, was also a policeman. He had driven straight from work at Cobram and was dismayed to find the house jammed with the “footy club crowd”.

The brothers told the police their father had come to pick them up from a neighbour’s place where they had stayed the night.

What they did not know for certain, but sensed, was something their mother had already told their older brother Jason: that King may have been having an affair with a woman neighbour. Kaye King had told Jason the suspected affair was the last straw; she was set to leave the erratic man.

On the short trip home, the boys wondered why their father was so anxious to start milking the cows around 2.30pm, much earlier than usual.

The boys claim he also made much of mentioning their mother’s absence as soon as they returned — then ordered them to look for her.

He told John to look near one haystack and the older boy, Peter, to look around another haystack: the one next to the old pig sty pit.

When the homicide crew got there late that night, they noted the suspicious circumstances but were frustrated that what they thought was the most likely crime scene — inside the house — had been destroyed by the gathering.

At that stage the death was being treated as a homicide until proven otherwise.

The police helicopter had been ordered for aerial shots and crime scene analysts booked.

But when the body reached the pathologist’s table in Melbourne next morning, the autopsy did not produce the “smoking gun” to make an easy murder prosecution.

In a key twist in a baffling case, the police interpretation of the pathologist’s carefully worded opinion meant that a suspected murder was now considered a freak accident.

Dr Shelley Robertson had done hundreds of autopsies then — and would do thousands more, later — but Kaye King’s death always troubled her.

A homicide detective, Graeme Collins, had noted the “oval-shaped dent” on the forehead, a double bruise around the left nipple, abrasions to ribs, belly and legs and bruised hands and broken fingernails.

Dr Robertson itemised 15 injuries divided between face, torso and hands. Any one of them — but not all of them — could have been caused by a fall.

And not one of them caused her death, which the pathologist believed occurred in the water.

Kaye King’s injuries were the sort people get in pub brawls, not in a simple fall.

And there was something else: a bruise under the skin on the neck above the collar bone, exactly where a man’s thumb could press if the victim had been grabbed around the throat.

Under “cause of death”, the pathologist wrote it could not be ascertained. This did not mean it was accidental or not suspicious.

The careful scientist had left open the way for further investigation, or so she thought.

Kaye King hadn’t been poisoned, shot or beaten to death — and she wasn’t sick, drugged, drunk or hurt enough to drown accidentally in the equivalent of a bathtub of water.

The big questions were: If she was unconscious when she went into the water, why was she? But if she was conscious, why not save herself?

It seemed a good starting point for a homicide investigation but the homicide squad didn’t think so.

When the pathologist’s carefully calibrated answers filtered through, someone ditched the investigation.

“It became ‘accidental’ overnight,” Ken Mansell would recall.

Detectives started to entertain theories that the dead woman might have hit her head on a fence post then fallen head first into the pit and drowned.

One said she might have tripped on a low wire and fallen in — or been “pushed” by a cow.

Someone briefed the media and killed the story, saying detectives had ruled out foul play. Which was puzzling, because a close reading of Dr Robertson’s report suggested foul play was certainly possible.

But the case was dead, even after a coroner made an open finding based on the pathologist’s report.

And that’s how it would have stayed if Kaye’s youngest child, Nicole, hadn’t returned to the district nine years later and asked the retired Mansell about her mother’s death.

It was easier for Mansell to be frank with a 23-year-old than with the traumatised 14-year-old schoolgirl of 1991.

She claims he told her about her father’s potential affair with the neighbour — and that King had been in financial trouble.

Mansell said he had saved the inquest brief just in case. Nicole told her brothers what Mansell had said.

Jason, the oldest, already knew their mother had planned to leave their father — taking with her a $60,000 insurance payout she had received for an arm injury.

King had sold the farm long before and moved to an empty shop in Stanhope with his youngest son, John.

Nicole had married and moved to Adelaide, and Jason and Peter were working in Sydney.

In 2004, Jason started digging, a search for justice that consumed every spare moment that year.

He spoke to Mansell, studied Public Records Office and coroner’s files, interviewed relatives and friends. He spent nights compiling a brief of evidence on the case.

He didn’t want to go to the police “half-cocked,” he explains.

“I was just looking for answers.”

For him, a key moment in his one-man investigation was the day a Public Records Office worker called to say there were documents from his mother’s inquest at the State Coroner’s office.

The worker faxed him the papers. The second page grabbed his attention.

“It was a letter from Dad’s solicitor asking them to hurry up and finish the inquest so he could finalise the claim on her life insurance policy.”

That’s when he realised his mother’s life had been worth $100,000 to his debt-ridden father.

Mansell recalled a scene outside the inquest hearing.

He claims King had approached him and demanded to know if the coroner’s open finding would affect his “insurance”.

At the time Mansell had assumed King was referring to the $60,000 injury compensation Kaye had got before her death, and he got angry.

He had pointed at King and warned him he could be charged with murder one day.

Now, in 2005, he was hearing that a $100,000 life insurance policy had been taken out just before Kaye’s death, the premiums paid by someone who was going broke.

Mansell urged Jason to take his evidence to the media — as well as to the police — to push for the homicide investigation that had been aborted back in 1991.

It worked.

King was charged with murder in September 2005, three months after a detailed account of the case was published on the 14th anniversary of Kaye’s death.

When the reporter who broke the story asked King if he knew that people suspected he had murdered his wife, he responded: “Hell, yeah.”

The first trial ran in late 2007. It ended in a stalemate.

Apart from evidence about King’s alleged motive and means to kill his wife, there was an extraordinary scene when a former striptease dancer testified what he had said to her one night at a strip club.

Susan Molnar swore that while she was with King at a strip club, King had told her he had killed his wife because he hated her.

Molnar said she did not know his name at the time but had immediately relayed the conversation to the barman who told her he recognised the man as Graeme King.

The second trial was held a year later, with a different judge.

After the jury was asked to return a verdict one way or the other — to prevent another hung jury — Graeme King was acquitted.

His children, in-laws and some former neighbours think that he still may have murdered her.

JASON, Peter and Nicole still live interstate and rarely go back to the district where their mother died and where their father, now in his 60s, serves out his life in a cell of a different kind.

The other son, John, was known to be living near Shepparton but has lost touch with the rest of the family.

The last time the four children talked about it together was in Sydney in early 2005, when Jason called a meeting to discuss the file of evidence he had gathered.

That day John broke his silence about what he had seen in the minutes before they found Kaye’s body.

He claimed their father had watched Peter intently while the confused teenager walked past the pit, as if expecting what happened next.

When Peter missed seeing the body the first time, he claims King had sent him around the haystack again, supposedly to check if the cows had pulled hay bales out of the stack.

It was only then that Peter saw the scene that played havoc with his mind until his father was finally charged 14 years later.

The trial didn’t send their father to a bricks-and-mortar prison but it answered many questions for them about exactly what had happened.

Nicole — now Mrs Ryan — has two children who haven’t met their maternal grandfather and probably never will.

Jason has three little girls not yet at school. Before they were born, he changed his surname to Thompson — his mother’s maiden name — to ensure they never share their despised grandfather’s surname.

Peter has recovered from the trauma that threatened to wreck his life. He works with Jason and is planning a future on a Snowy Mountains grazing property with his long-term partner. Jason is manager and part owner of the New South Wales branch of the country’s biggest fleet sign businesses.

They rarely go back to Katandra because it has bad memories and they want to avoid the father they don’t talk about.

But early last year, Jason and Peter returned for the burial service of an old family friend, Pam Burgmann, who died after a long illness.

They needn’t have worried that their father would be there. The dying woman had stipulated he couldn’t come.

Originally published as Death on a dairy farm: The search for answers Kaye King’s children never got