Andrew Rule: Why these four men are suspects in Beaumont children case

In 1966 times were changing — but some things hadn’t, which meant an anonymous monster was able to steal away three children from a beach without trace. NEW PODCAST

Cold Cases

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cold Cases. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There have been other abductions and murders in the past 50 years, each as terrible as the next for the families left behind.

But no other crime has grabbed the nation’s imagination like the one still known simply as “the Beaumont Children”.

It is our version of the Lindbergh kidnapping in America, the Moors murders in Britain.

When a child vanishes, parents are condemned to the worst torment.

But to lose all your children is beyond belief, loss on a scale that Australians imagine could only happen in wartime genocide far away. It happened to Jim and Nancy Beaumont.

The new year of 1966 was the start of a new era.

Decimal currency was minted and printed ready for release on February 14 to replace pounds, shillings and pence; indestructible Prime Minister Robert Menzies was retiring after a phenomenal innings and rock ’n’ roll was taking over popular culture as the baby boom turned into a tidal wave of teenagers dancing to a brand new beat.

Times were changing — but some things hadn’t, which meant an anonymous monster could move among us without trace.

It’s hard for anyone born since the 1960s to imagine a world with no credit cards, no computers, no security cameras, no mobile telephones and only primitive recording equipment: none of the things, in fact, that now make it almost impossible for anyone to move around without leaving an electronic trail.

One technological advance actually made life easier for wrongdoers: cars, scarce in the 1950s, were by 1966 relatively plentiful and affordable, so that anyone who had one could move across a city, a state or the entire country almost as easily as we can today — but without being automatically recorded along the way.

Whoever lured Jane, Arnna and Grant Beaumont from Glenelg Beach that hot afternoon faced nothing more than the uncertain impressions of random eyewitnesses.

Satellites circled the planet and scientists were close to putting man on the moon, but forensic science and security surveillance techniques lagged well behind the space race: in 1966, the odds still were that an unknown offender not actually caught at a crime scene could get away with murder, probably in a car with bodies in the boot.

In the Beaumont case, he has got away with it for more than half a century.

It was probably the crime that did most to change Australians’ perception of safety.

We went from a casual and carefree society in which most kids played unsupervised to a grave new world in which parents live in fear children will be harmed.

It was the end of innocence. So who was the killer that changed a nation?

Investigation bungles, stunts and false leads

Inevitably, the 50th anniversary of the Beaumont case prompted what is called a “new lead”.

Such “leads” have over the years come from the mentally ill, from cruel hoaxers and from sincere well-meaning people.

They all share one thing: so far, not one has been useful.

Neither has the police work that began with a bizarre artist’s impression of the thin, blond man with the Beaumont children when last seen.

It was, after all, Australia Day, and the artist (and, no doubt, many police) had been celebrating in traditional style — beer, burned sausages and more beer — before being called in that evening.

The artist would later admit he was so liquored up he could hardly hold his pen, which explains why the sketch looks more like an alien than human.

It was a bad start to an investigation that never got much better.

From the beginning, the case attracted stunts that made headlines but no headway in the investigation.

The first was the arrival of celebrity corrupt cop Ray “Gunner” Kelly, flown from Sydney by a newspaper not to make an arrest so much as to create a sensation.

Kelly, the Roger Rogerson of the time, left town after just one day, his mission accomplished: he had posed for photographs, tossed off a few quotable lines and no doubt pocketed his fee. It was a circus.

So was the arrival a few months later of a Dutch “clairvoyant”, Gerard Croiset, who led investigators and reporters around randomly before predicting the children’s bodies would be found under or near a new building that had been under construction at the time.

A public subscription paid for concrete to be dug up. Nothing was found.

Decades later, when the building was demolished, the entire site was dug over, but still nothing.

The police, meanwhile, plodded on, fielding letters and calls and checking “sightings” of the children all over Australia and beyond.

Each lead gave the tortured Beaumont parents hope.

Only to dash it again and again.

For years Nancy Beaumont insisted on staying at their now haunted house, in case her kids came home.

Probably no one except the killer — if he’s still alive — knows who did it.

The odds against the case being solved are 1000-1 and drifting.

The killer is either an “unknown unknown” — a secret psychopath who has never come to police attention — or a “known unknown”, one of a few viable suspects linked to the crime by flimsy circumstantial evidence and hearsay.

Only one of that group is still alive, and he is in his 70s.

BEVAN SPENCER VON EINEM

Authorities will keep finding reasons to keep Bevan Spencer von Einem in jail.

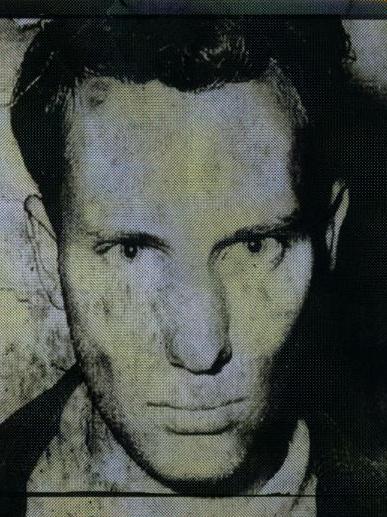

Von Einem was an accountant by profession, a depraved sex killer by compulsion.

He was arrested and later convicted over the abduction, torture and murder of Richard Kelvin, teenage son of Adelaide TV news reader Rob Kelvin.

Young Kelvin’s abused body was found in bushland outside Adelaide six weeks after he vanished near his parents’ home on June 5, 1983.

Experts believe he had been kept alive most of that time, in a drugged state, eventually dying from internal injuries inflicted with a bottle or other blunt object.

It is unlikely von Einem acted alone.

It is known he bribed transvestites with drugs to lure young men into cars, and that he knew a core group of at least three other deviates.

Some police believe the group, dubbed “The Family”, included a businessman, a doctor, a lawyer and the brother of an Olympic athlete.

They have been able to avoid arrest while von Einem serves his sentence and keeps silent about who else participated in the murders of Kelvin and four other young men abducted between 1979 and 1983.

In 1966 von Einem was turning 21.

It would later be revealed he was spotted in film taken at Glenelg beach days after the Beaumont children disappeared.

Deviant offenders are drawn to the scenes of their crimes.

Some think von Einem’s relative youthfulness in 1966 makes it unlikely he was the killer.

It is not a persuasive argument, as the sexual sadism he demonstrated in the Kelvin case would have surfaced at puberty.

Another argument against von Einem as a suspect is that witnesses estimated that the thin, blond man they saw with the children was probably “in his 30s”.

Witnesses are notoriously unreliable in describing anything seen fleetingly, and police sometimes confuse or distort what a witness means, so it is risky to discount suspects as “too young” or “too old” on the basis of statements that can no longer be checked.

As for von Einem being capable of a triple murder at his age, at least one other suspect demonstrated he was a compulsive sexual psychopath when barely in his teens.

DEREK EDWARD PERCY

Even as a child, Derek Edward Percy did things that meant his mother never left him alone with other children.

While at school at Mt Beauty, where his father was an engineer, he would steal and wear women’s underclothes and display violent sexual fetishes.

Percy, who died in 2013, has become a prime suspect for the Wanda Beach murders, which happened in Sydney a year before the Beaumont children vanished.

At Wanda Beach, a teenager matching the then 17-year-old Percy’s description was seen near 15-year-olds Christine Sharrock and Marianne Schmidt not long before they were killed together.

Alcohol was found in their systems, which tallies with “plans” Percy wrote, found after he was arrested more than four years later for murdering 12-year-old Yvonne Tuohy at Warneet in Victoria.

At the time of the Wanda Beach murders, he lived just two kilometres from where both girls lived.

When Percy killed Yvonne Tuohy he was a naval cadet at the nearby HMAS Cerberus training base.

Police who worked on the Tuohy murder had no doubt Percy would have been capable of similar crimes in his early teens.

Other cases were linked to him by “similar fact” and circumstantial evidence.

He became the main suspect not just for the Wanda Beach horror but for the murder of Simon Brook, 3, killed in Sydney in 1968, and for the murder of Allen Redston, 6, in Canberra in 1966.

And he would eventually be named by a coroner as the murderer of Linda Stilwell at St Kilda in 1968.

There was a common denominator.

Most of the murders were near water and Percy had been in the vicinity at the time.

Percy’s father had introduced him to sailing relatively young — perhaps as a way to occupy an obviously disturbed boy.

Father and son had a small yacht, which they towed to regattas, often interstate.

One of the most popular regattas on the sailing calendar was held off Glenelg on the Australia Day weekend in 1966.

Percy was barely 18 then but if he’d killed two 15-year-old girls at Wanda Beach a year earlier, there was nothing to stop him killing nine-year-old Jane, seven-year-old Arnna and Grant, 4.

Against the theory is that the Beaumonts’ bodies were never found, suggesting cool planning and local knowledge rather than an impulsive crime by a teenage visitor.

Then again, even evil people can get lucky.

Percy was lucky his respectable parents apparently never suspected anything sinister about their strange son.

Because where he went, children were killed.

The same could be said for a far more sophisticated child killer.

JAMES RYAN O’NEILL

By the time he was jailed for murdering a little boy in Tasmania in 1975, the smooth-talking murderer who called himself James Ryan O’Neill was 27.

The scotch College old boy from Melbourne had been raised as Leigh Anthony Bridgart.

He had fled Melbourne for outback Western Australia in 1971 after being charged with 12 counts of abducting and molesting children.

While he was in the Kimberley a young Aboriginal boy, Jimmy Patrick Taylor, went missing, presumed murdered.

Two months later O’Neill moved as far as he could — to Tasmania.

In 1975, O’Neill was heading to pick up his wife and newborn son from hospital when he abducted and killed a nine-year-old boy, Ricky John Smith.

Before police caught him, he murdered another young boy, Bruce Colin Wilson.

He was arrested trying to abduct two more boys.

Retired Victorian detective Gordon Davie and a former crime reporter, Janine Widgery, interviewed O’Neill in prison.

He said he’d committed his first murder at 15, in 1962.

And he mentioned the Beaumonts.

Davie was intrigued that O’Neill did not deny murdering the Beaumonts, instead evasively saying he lived in Melbourne at the time, not Adelaide.

But Davie found that O’Neill had visited the Coober Pedy opal fields — via Adelaide — about 15 times.

Something he said convinced Davie he had disposed of a body — or bodies — in one of the thousands of abandoned mine shafts there.

Davie puts O’Neill on a “very short list” of suspects for the Beaumont case.

He says a sex killer doesn’t start offending at 27, O’Neill’s age when he was finally arrested. He had roamed Australia for a decade before that.

And everywhere he went, children went missing.

ARTHUR STANLEY BROWN

Brown was an old man when he was named prime suspect for killing two little sisters in August 1970 in his home town of Townsville.

Susan Mackay was five, Judith was seven.

They vanished as they walked to school.

Their bodies were found in scrub outside town two days later.

Brown was so well-known in Townsville he was invisible.

As a government maintenance worker, he worked on police stations, courthouses and schools and enjoyed the perk of five weeks’ annual leave, which allowed him to travel interstate.

Local teachers, police and lawyers all knew the neat, lean little man well enough not to give him a second thought.

But they didn’t know him as well as younger members of his wife’s extended family.

They knew he was a child molester but kept their sordid secret until one woman finally spoke out, suspecting something even more sinister.

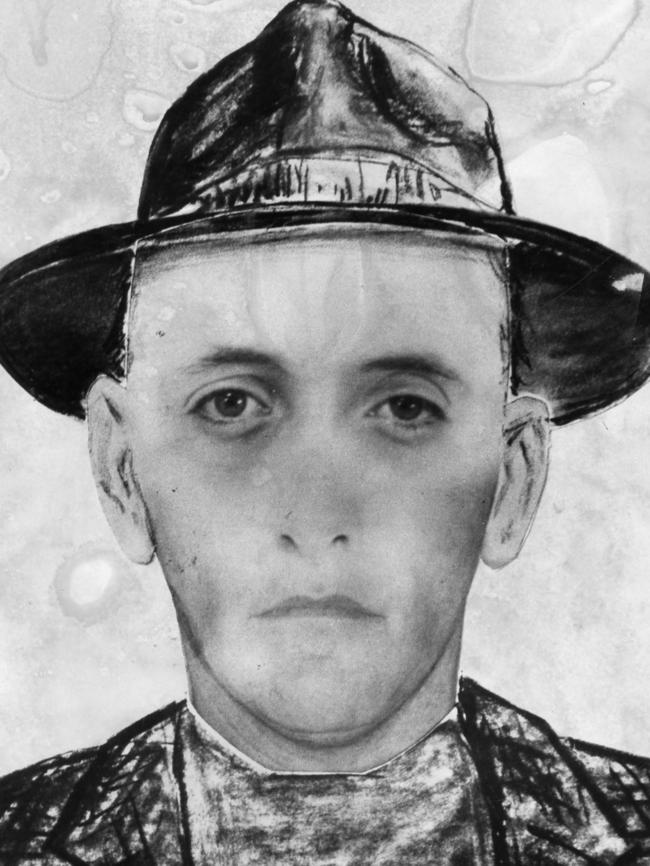

That was in 1998, when Arthur Brown was 86, although still plainly recognisable as the lantern-jawed character photographed soon after World War II.

He’d looked fit, and much younger than his years, for decades.

With his wide-brimmed hat on, he could pass for someone many years younger.

Brown’s first wife died in suspicious circumstances in 1978. His second wife was the dead woman’s younger sister, a tiny woman who pandered to his tastes by wearing children’s pyjamas to bed.

When the police finally came for him, Brown didn’t seem shocked.

But he blurted something about the Mackay sisters’ murders that a prosecutor would later label “consciousness of guilt.”

As soon as he got a lawyer, Brown fell silent, and developed symptoms of dementia that would ultimately see murder charges dropped on grounds that he wasn’t fit to plead.

One problem in prosecuting him was that all his work records had been lost — including, crucially, when he had taken leave.

Which was a pity, because it might have indicated if he was on one of his regular interstate motoring holidays in 1973, when Joanne Ratcliffe and Kirste Gordon went missing in Adelaide.

Several witnesses saw a thin-faced man wearing a wide-brimmed hat carrying a small girl and leading a bigger one from Adelaide Oval that day.

When police compared identikit sketches of that suspect with photographs of Arthur Brown, the resemblance was striking.

Whether the same thin-faced man had been at the city’s Glenelg Beach on Australia Day seven years earlier, in 1966, no one knows.

Officially, the case has never closed, but time is against it.

MORE RULE:

HOW TRADIE WRONGLY BECAME MURDER SUSPECT

Originally published as Andrew Rule: Why these four men are suspects in Beaumont children case