How Craig Cameron Rogers became the face of cold case murders

For 28 years, Craig Cameron Rogers was the “only” suspect in the murder of Geelong woman Annette Steward. But now, after decades of proclaiming his innocence, the tradie has been cleared of any wrongdoing. Andrew Rule recounts the fascinating investigation.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For most of the last 28 years, more than half his life, a Surf Coast tradie has lived with being branded the “only” suspect for murdering his workmate and sometime girlfriend, Annette Steward, in 1992.

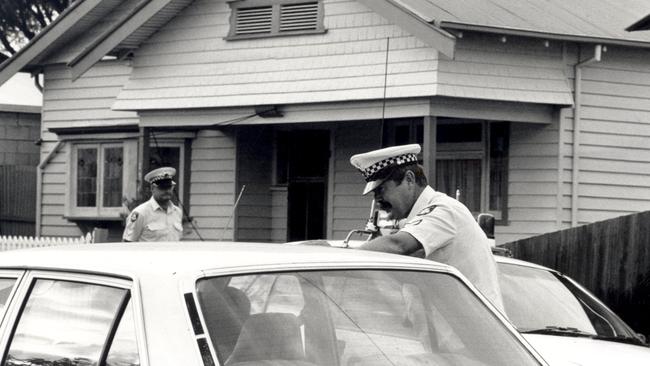

The mother of two was found naked in the bedroom of her home in Hope St, Geelong West, on March 18 that year. She had been strangled with an electrical cord.

It was a terrible crime that affected her family, especially her two young children. But the fact that it went unsolved month after month, year after year, also took a toll on the man widely blamed for it.

The ordeal of Craig Cameron Rogers began one morning in March 1992, when he got to work at the Winchester ammunition factory at Point Henry, east of Geelong city centre.

His colleague and on-again, off-again partner Annette Steward, did not turn up for work. Asked where she was, Rogers said something stupid that soon came back to haunt him. He said flippantly something like “a truck ran over her”, a comment that would intrigue investigators before the week was out.

Given that Annette’s battered body was not found until several hours later, it seemed a slightly sinister remark to make about the friendly, outgoing woman who loved life and meeting people. Context matters, and when investigators found out she had fallen out with her young lover — Craig was 23, Annette 28 — they couldn’t help feeling they had their best suspect.

Steward had told friends that Rogers had forced a door at her house to get into her bedroom a few nights earlier.

But Craig Rogers never moved away from the Geelong area and never wavered in proclaiming his innocence. So when Perth detectives arrested a Darren John Chalmers last Sunday for murdering a woman neighbour eight months ago, it must have been a great relief for Rogers that Chalmers was immediately also nominated for the Steward murder.

Victorian detectives went to Perth to interview Chalmers after consulting West Australian investigators about an imminent breakthrough in the cold case.

The now-retired detectives who originally investigated Annette Steward’s murder are pleased that her adult children, Aaron Steward and Jacinta Martin, might finally have answers about the crime that led them to leave Geelong for northern Queensland.

Aaron Steward said from Cairns this week he was so young when his mother was killed that he knew little about the tragedy or those who were investigated over it. Craig Rogers was even less inclined to talk about the bruising experience of being the target of suspicion for so long. Both appear to have had some warning about developments in Perth leading to Chalmers’ arrest.

Chalmers came under police notice in mid-May, when a retired music teacher who lived two doors from his house in suburban Medina vanished the day after buying flowers at a Bunnings store on May 11.

Neighbours knew that Chalmers was “friends” with the vanished woman, Dianne Barrett, and suspicions grew. He was formally charged and his house declared a crime scene when the missing woman’s remains were found in bushland 30km away last weekend.

Victorian detectives were on standby to interview Chalmers about one of the cold cases that has tantalised them for decades.

If Chalmers is found guilty of the Barrett murder, it is unlikely he would face trial for the Steward case for many years. If convicted in Perth, he would most likely serve a long sentence there before being tried in Victoria.

Chalmers was always on the periphery of the Annette Steward case. Two days before the body was found at her West Geelong house, Chalmers had visited in company with another friend of hers, Keith Pengelly, to fix her television aerial.

Chalmers was questioned, but mainly about Pengelly’s movements, as Pengelly had admitted having a relationship with her. Neither man then seemed as strong a suspect as the unhappy Craig Rogers – but Chalmers moved interstate soon afterwards and Rogers stayed around.

When the Sunday Herald Sun contacted Craig Rogers at his Surf Coast home mid-week, he growled that he had nothing to say about the case. It’s hardly surprising he is gun shy, given that he was ambushed by a television crew after a $1 million reward was announced to catch the killer in 2015. Being made the poster boy for cold case murders is no way to make new friends.

The Steward case underlines how difficult it can be for investigators to draw watertight conclusions, even in cases where strands of evidence seem to suggest one person’s guilt.

The same crew of investigators also worked on the murder of a young Ballarat nurse whose presumed killer is known to all but who has escaped arrest so far.

Nina Nicholson was just 22 when she was killed at the back door of her home in Clunes on a wet September night in 1991, six months before Annette Steward’s death. Her murder followed months of growing fear that began after her husband Robert Nicholson started an interstate trucking business.

It was obvious in the neighbourhood that when his semi-trailer wasn’t parked beside their house, he wasn’t home. Nina was reluctant to say why she was nervous about staying home alone. Then, about a year before she was killed, something terrified her.

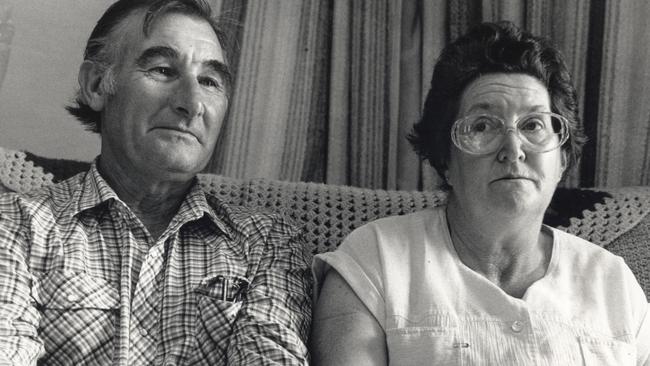

Nina called her parents about midnight, hysterical. She said she could hear an intruder outside the house. Her mother kept her on the line while her father “Spike” Jones drove the short distance to his daughter’s place. He saw no sign of the intruder or any strange cars.

Later on, the absence of anything out of place suggested that whoever had spooked Nina was on foot and might live nearby, but at the time it just deepened the mystery. Jones, a respected local CFA leader, was happy to find his daughter safe and take her home to stay the night.

It was only later that the likelihood struck him that the intruder lived close by. When Nina revealed she had heard someone creeping about outside her house several times, her parents insisted she stay with them whenever her husband was doing an overnight trip.

Nina would sleep at her parents’ house if she was working day shift in Ballarat. If she was working night shift, she would eat with her parents and younger brother Andrew, then go home to change for work.

It was a simple precaution and it put the family at ease. But it wasn’t enough. On the night she died, Nina had eaten with the family and watched television with her mother. About 8pm, she went home to get ready for her shift, which started at 9.30, a half-hour drive away in Ballarat. It was raining hard. The last thing her mother said to her was to be careful on the road.

About 9.40pm, the Jones’ telephone rang. It was a workmate in the children’s ward at St John of God Hospital. Nina had not turned up. Andrew woke his father. They assumed Nina’s car had broken down on the Ballarat road but they drove past her place to check.

When Spike spotted her white Nissan in the lane beside the house, he turned in. His headlights lit the back door. Nina was lying on the veranda in her blue nurse uniform, her head bleeding.

Her father took one look and knew it was too late.

Nina’s handbag was beside her. In it were keys, needlework she was working on, money and credit cards, all untouched. It wasn’t a robbery.

They rang the ambulance and the local policeman and Spike raced home to get Nina’s mother, Ann.

As Ann cradled her daughter’s head, she saw a man watching from the shadows. He was clean-shaven with dark hair and was wearing a white shirt. She did not mention it to the policeman, as she thought he had already seen him.

The policeman tried resuscitation while they waited for the ambulance. The first thing the homicide detectives found was that Nina Nicholson and her family had lived a blameless life. There were no skeletons in their past to suggest the attack was anything but what it seemed – senseless and unprovoked.

It looked as if Nina had surprised a trespasser who had panicked and attacked. A likely explanation seemed to be a “peeping tom” that she knew by sight. In the end, there was the shortest of shortlists.

The detectives were convinced they knew who did it. They still are. But this time, they are overwhelmingly likely to be right.