Mick Hawi leapt out of the taxi and stormed through the front door of his parents’ home.

The 28-year-old’s muscular frame was covered in wounds. He was still bleeding, but not heavily. Hawi’s adrenaline was pumping and his rapid heavy breathing reflected that. He had almost forgotten to pay the cab fare from Sydney Airport to his father’s southern Sydney abode that, for now, was acting as a safe house.

He put a towel on his wounds and called his lawyer to explain the situation he found himself in on the afternoon of Sunday March 22, 2009.

Hawi had gotten in a wild brawl inside Sydney Airport.

A rival member of the Hells Angels might be dead. Anthony Zervas’ beaten body looked dead, but Hawi didn’t hang around long enough to get the diagnosis.

“Are you injured?” the lawyer asked.

Hawi replied: “Yeah, I’m cut.”

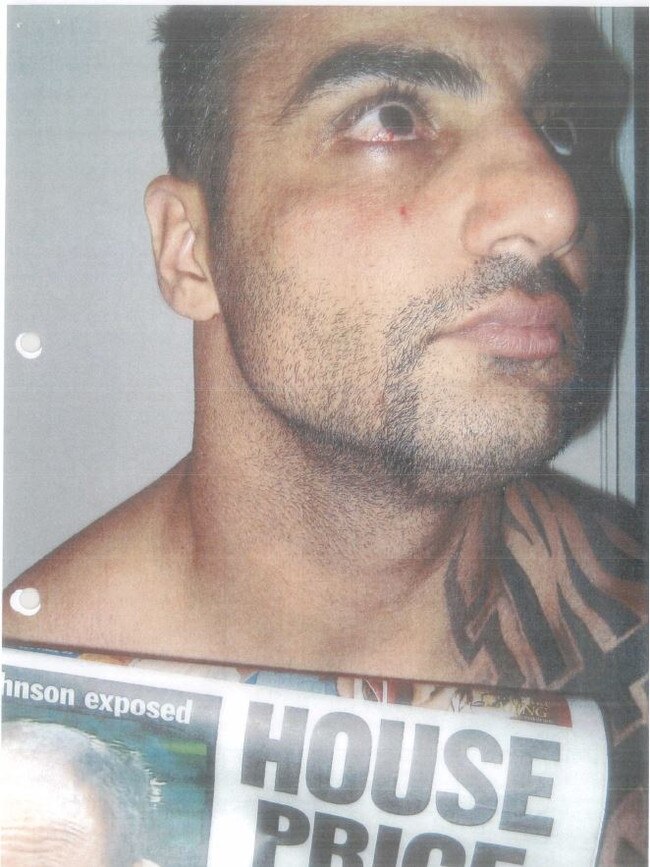

“Grab a copy of today’s paper,” the lawyer said. “Get the date on the front of the paper and hold it next to every wound and take a photo.”

Hawi was likely to be charged with something. No one gets into a brawl at Sydney Airport and goes unnoticed.

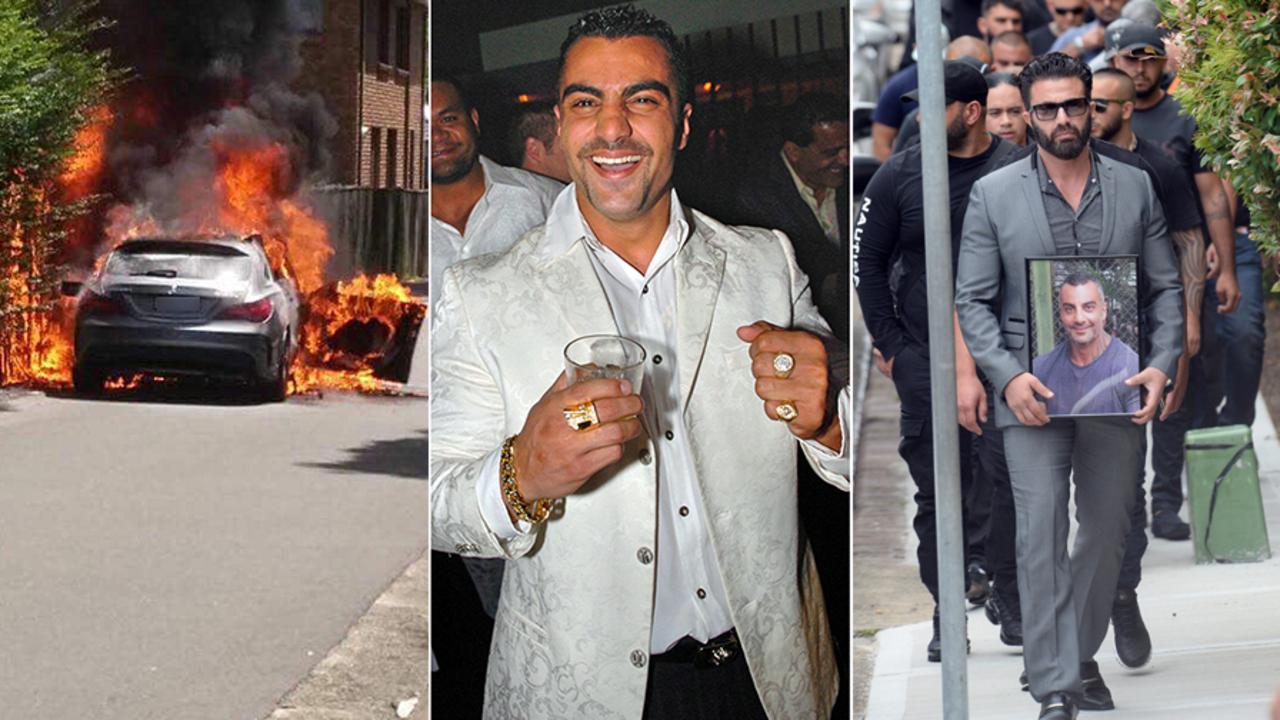

Chapter 1: Tattoos that told the life story of Mick Hawi

Chapter 2: Comanchero boss Hawi a rare one-woman bikie

Chapter 3: Bikie brawl and airport killing changed Sydney forever

Chapter 4: Depressed Hawi’s world falls apart

Chapter 5: Money troubles before Hawi’s life ends in a hail of bullets

So the quick thinking lawyer figured if Hawi could document that his wounds happened today there was a possibility of defending whatever charge he would face on the grounds of self defence.

Hawi’s wife Carolina Gonzales and their young son arrived soon after. She was brought to the home by senior Comanchero Duax Ngakuru.

Ms Gonzales went to the upstairs room of the house and sat on the couch to watch the TV. News flashed across the screen that a man had been killed in a brawl at Sydney Airport.

They didn’t go to the hospital to get Hawi’s injuries stitched. Instead, the group travelled to Hawi’s cousin’s home, picking up a copy of The Sunday Telegraph on the way.

With Hawi holding up the paper, photos were taken of bruising around his right eye and a lesion on his eyeball.

There was also a gaping wound on the top of his blood soaked left hand

Further up on his tattooed left arm was a 15cm long cut on the underside of his bicep. His shoulder was also missing a chunk of skin and was glistening red.

QF430: THE LEAD UP TO THE KILLING

In the period preceding the Sydney Airport brawl, relations between the Hells Angels and Comanchero had ranged from overtly tense to homicidal.

A Brighton-Le-Sands business associated with the Hells Angels had been firebombed, court documents said.

Graffiti was sprayed on the front of the business that read “ACCA”, an acronym that stood for “Always Comanchero, Comanchero Always.”

A Petersham tattoo parlour controlled by the HA was sprayed with bullets in a driveby shooting.

The gang’s clubhouse on Crystal St, Petersham, had also been bombed.

The Hells Angels blamed the Comanchero for all of the attacks.

So the fact that then Hells Angels president, Derek Wainohu, Hawi and four of his Comanchero underlings found themselves seated within spitting distance of each other on a flight from Melbourne to Sydney on March 22, 2009, was an unfortunate coincidence.

Qantas flight 430 departed Melbourne about midday.

Immediately after he boarded the plane, Hawi spotted the Hells Angels’ boss who was flying alone.

Throughout the flight, passengers watched nervously as Hawi went out of his way to walk up and down the plane, glaring at Wainohu and exhibiting animosity towards him.

According to court documents, another passenger overheard Hawi telling his crew: “Get the guys to meet us at the other end.”

Wainohu did the same thing, using his phone to call in backup from his Hells Angels troops once he landed in Sydney.

Seven Comanchero and seven Hells Angels rushed to the airport.

The Comanchero reinforcements came in two cars and parked illegally, leaving the vehicles outside the lower baggage claim of Terminal 3 while they ran inside and up an escalator.

Five passed through the airport’s metal detectors and ran to Gate 5 to meet the arriving flight. Two Comanchero remained out the front.

The Hells Angels contingent included brothers Peter and Anthony Zervas, who also rushed to the scene.

THE FIGHT

Weighing in a 58kg and standing a diminutive 161cm, Anthony Zervas should not have been up for a fight with anyone.

But given the astonishing amounts of illegal substances he had ingested on March 22, 2009, he was ready to take on 1980s Mike Tyson.

Doctors later found the concentration of cocaine in Zervas’ blood system was 25 times higher than what would normally be considered fatal.

If Hawi didn’t kill Zervas that day, doctors later gave evidence in court that the cocaine in his blood stream coupled with a methadone dose that was three times higher than the average fatal dose would have.

Regardless, Zervas was breathing fire and ready to go, not concerned that his side was on the wrong end of a ten versus five man match up.

As soon as they departed Gate 5, Hawi approached Wainohu on the concourse and the pair started arguing as concerned travellers kept their distance.

Hawi could see his Comanchero reinforcements moving towards him at a fast pace.

They had parked their non-bikie looking silver Toyota Aurion illegally at the front of the T3 arrivals terminal. Within minutes a dutiful Airport parking inspector slapped the vehicle with a $132 fine.

Hawi punched Wainohu and sparked the brawl that would forever change security at Sydney Airport.

The two groups now converged and faced off as frightened members of the public, which included children and elderly, watched on.

Hawi ended up on the ground fighting with one of the Hells Angels.

A number of the Comanchero chased one of their rivals along the concourse, punching and kicking him until he went to ground, where they punched and kicked him some more.

Then the fighting stopped.

The warring Comanchero and Hells Angels regrouped and headed for the exit, to the relief of the stunned members of the public who watched the brawl unfold.

One witness later recalled while giving evidence in court that Hawi called out threats to the effect of “you’re dead, you’re f...kng dead” and “next time we see you, you’re going to have bullet holes through you. You are a dead man walking.”

The 10 Comanchero then exited the Airport’s secure area and into Terminal 3 and met up with two more gang members.

They also spotted five Hells Angels near the check-in counters and moved quickly in their direction.

Hawi exchanged words with Peter Zervas, who was wearing a set of knuckle dusters.

Anthony Zervas then made his move. He pulled his hood over his head, approached Hawi from behind and attempted to stab the Comanchero boss in the temple with a pair of scissors, injuring Hawi’s eye, hand, shoulder and tricep.

As this occurred, one of the Comanchero yelled “He’s got a nug”, which is a slang term for a gun.

The fight was on again.

It erupted behind the airport check-in counters and moved towards the front of Terminal 3.

Stunned witnesses preparing for their flights watched on as punches flew everywhere and described it as an “all-in brawl” and “an explosion of fighting” that was “incredibly violent”.

The fight then broke into smaller groups. The brawlers picked up 12kg bollards and hurled them at each other.

The final act of the fight took place one or two metres in front of two elderly people who were seated on a bench waiting for a wheelchair.

Anthony Zervas was pursued to the front of the terminal where he ended up on the ground near the glass wall.

A member of the Comanchero — who a NSW Supreme Court Justice would later rule was not Hawi — picked up a bollard and rammed it downwards so the base struck Zervas.

Anthony Zervas was dead.

Officially, he died from the combined effects of blunt force injuries to the head and stab wounds to the chest and abdomen, at least one of which was caused by a pair of scissors.

From the time Zervas attempted to stab Hawi to the point that he died had unfolded in just 36 seconds.

The Comanchero fled while terrified members of the public called triple-0.

The brawl sparked a massive crackdown on bikies.

Then then NSW Premier, Nathan Rees, immediately announced he would meet the Police Commissioner, Andrew Scipione, to discuss tough new anti-bikie legislation.

“I was sickened by this brazen attack. Violence of this nature particularly in front of families nd children is nothing short of disgusting,” Mr Rees said.

Mr Scipione announced the formation of an anti-bikie squad known as Strike Force Raptor just five days later.

Laws were introduced that effectively banned bikie gangs.

THE ARREST AND CHARGES

Hawi was not charged immediately after the Airport brawl.

Thanks to CCTV cameras being pointed the wrong way, police were not certain who actually took part in the brawl and were forced to work through the painstaking task of trawling through 120 hours of other footage to find the answer.

In what was perhaps a short sighted move, Hawi took the opportunity to double down and get on the front foot in the public relations stakes.

He put out a press release through his lawyers calling a peace meeting between other bikies.

And he then poked the bear by criticising the police for what he said was an attempt to cover up their failures to stop Zervas’ death.

Police told the media that Hawi was calling for peace because he was “just a gangster” who was now worried the airport violence would affect his business dealings.

When investigators finally got through watching the footage, they realised Hawi was involved in the brawl.

By April 2, police had lost confidence that Hawi would hand himself in and officers from Strike Force Raptor raided his Bexley home that day, only to find no one was home.

Hawi’s lawyers told police there was now a price on his head and walking into a police station under the glare of the media was a dangerous proposition.

A heavily pregnant Ms Gonzales was also struggling to deal with what was unfolding.

Hawi finally handed himself in on April 6, 2009 and was charged with affray. Bail was refused and he was locked in a cell.

As police collected more evidence, they added to the tally and on May 19 charged him with rioting.

Hawi faced court the following day and was released on bail, much to the chagrin of the police.

His freedom wouldn’t last long. Police charged Hawi with murder on June 30.

He was again refused bail and would remain behind bars for the next five years.

It was devastating for Ms Gonzales who was standing by her man and was devastated that he would not be there to support her during the birth of their second child.

She would give birth nine days after the murder charge was laid.

“I did not comprehend what was happening,” she would later write in an affidavit that was tendered to court. “Mick had promised me that he had not done anything, so I could not understand why this matter was continuing and why he had been refused bail.

“The stress of Mick’s arrest for murder so late in my pregnancy resulted in me being hospitalised on several occasions,” she wrote. “Mick’s absence during my labour made it very much more difficult.

A defiant Ms Gonzales also accused police of being calculated in their timing with the murder charge.

GALLERY:

“The timing of the arrest was in my view calculated to destroy Mick and me,” Ms Gonzales wrote in the affidavit.

It was also difficult on their older son.

“It was very difficult for me to explain to (our son) on the day of Mick’s arrest for murder as to where his father was …,” Ms Gonzales wrote. “I had to tell him that ‘Dad has been called away for a while on work’.”

The boy, who was very close to his father, began to act out, Ms Gonzales wrote.

“Since Mick’s arrest, Adam has begun to hate me, blaming me for the loss of his father” she wrote. “He is very demanding of attention, he wakes up in the middle of the night and starts crying, calling for his father.”

She concluded the affidavit with a definitive statement: “I know my husband. I have known my husband since we were 15-years-old. I know he did not murder anyone.”