Could two matches played on a foreign island in the shadows of World War II be the true beginning of the world’s most fiercely fought rugby league contest?

IT IS THE NIGHT of June 11, 2008, and as it is whenever a State of Origin match is telecast, the TV at the neat little house in Mill Street, Charters Towers, is on full volume.

Ernie Hill, 87, suffered hearing loss serving as a machine-gunner in the Pacific during World War II, but nothing can stop him from savouring his great love for rugby league. Club games, internationals and especially Origin, if it’s on the telly Ernie watches it, with the sound reverberating off the walls.

On this night the commentators seated high in the stand at Brisbane’s Suncorp Stadium are talking about the first Origin ever played, and how far the concept of players representing their home state, rather than the state in which they play club football, has come since.

“The first game was 28 years ago, on this very ground,” one says.

Ernie sits up in his chair and raises his voice over the din.

“No, it wasn’t!” he shouts at the screen. “It was on Bougainville in 1945. I should know, I was there ... and I’ve still got the program.”

ON JUNE 5, TENS OF THOUSANDS of Queenslanders will make their annual pilgrimage to Suncorp Stadium in Milton, just west of the Brisbane CBD, for the first match in this year’s State of Origin series.

Many will follow a wellworn path. They will walk north-west down Caxton St from Petrie Terrace, take a shortcut across the grass verge along the front of the stadium and line up to have their photographs taken alongside the statues of four of Queensland’s Origin greats:

Darren Lockyer, who played a record 36 games in the maroon jumper; Wally Lewis, regarded as Queensland’s undisputed king of Origin, Arthur Beetson, the man credited with kick-starting it all, and Mal Meninga, who left an indelible Maroon mark on and off the field.

From the requisite photo-op, the Maroons faithful, many with painted faces and proudly wearing jerseys emblazoned with the names of their heroes on the back, will move further up the pathway for a slow stroll past the commemorative plaques embedded in the concrete concourse.

Every player who has taken the field for Queensland in an Origin match since Beetson led a team of local youngsters and Sydney-based expats to a win over the hated Blues of NSW on July 8, 1980, has a plaque on the walk of fame.

For younger fans it is the names of players like Billy Slater, Johnathan Thurston and Greg Inglis that attract the most interest.

Those with a sense of history prefer to pay homage to “The Originals”, like Beetson, Lewis, Mal Meninga, Rod Reddy, Johnny Lang, Chris Close, Kerry Boustead and Rod Morris.

They are all there, the superstars, the characters and the quiet achievers whose names will be forever linked to the multimillion-dollar TV ratings phenomenon that is Origin: Alfie Langer, Gene Miles, Fatty Vautin, Trevor Gillmeister, Gorden Tallis, Petero Civoniceva.

Those who have played 20 games and those who have played just one; every Queenslander who has earned lifetime membership in the state’s most exclusive club, the FOGs – Former Origin Greats.

Yet there are 13 names that won’t be read. Names such as Jack Barnes, Bobby Williamson, Jim Christopher and Hec Bradshaw. They don’t have a plaque on Origin Walk and only one warrants a mention on the nearby wall that bears a list of every player who represented Queensland before 1980.

But on September 16, 1945, at a ground in Torokina, Bougainville, they did represent Queensland against NSW in what rugby league historians consider the game’s first-ever State of Origin series.

IN 2011, QUEENSLAND RUGBY league stalwart Kevin Brasch received a phone call from Major John Wright, curator of the military museum at Brisbane’s inner-city Victoria Barracks. Retiring as chairman of the Brisbane Rugby League in 2007, Brasch remained active in the game as a member of the QRL History Committee.

Major Wright told Brasch he was updating the museum’s inventory and was seeking information about a trophy, made from a Japanese artillery shell, that had been awarded to the winner of a two-match “Origin” series played between Australian troops on the island of Bougainville, about 1500km north-east of Cairns, days after the end of World War II.

The trophy was engraved with the names of the players in both teams, and Wright was seeking to trace any relatives.

The call proved timely. The QRL History Committee holds regular public lectures covering colourful and little-known chapters of rugby league’s past. Committee secretary Greg Shannon, 38, was scheduled to give the next lecture, in May 2012. His subject: Rugby League in World War II.

“Kev told me about the trophy and we went up to the barracks to see it and copied down all the names,” he says.

“My talk was about rugby league in all the armed forces. At the end I told a story as an example of the game in each of the services, navy, air force and army. I used the Origin series in Bougainville as the army example. It wasn’t the major part of the lecture, but it has turned out to be the most interesting.”

Shannon, an agronomist working in the sugar industry at Tully, North Queensland, found that rugby league was the odd game out when Australia went to war in 1939.

Rugby union, Australian rules and cricket were the official sports of the Australian armed services. It was only through the lobbying of James Larkham, state Member for Rockhampton and a former president of the QRL, and Ingham-born Arthur Fadden, briefly prime minister in 1941 and inaugural president of the North Queensland Rugby League, that rugby league was adopted by the military.

Matches between battalions became regular events. There were even “interstate” clashes between Queensland and NSW battalions, although just like the criterion that led to the introduction of State of Origin in 1980, selection was based on place of enlistment, rather than place of birth.

The most famous example is South Sydney great Jack Rayner who was born at Coraki in Northern NSW, but joined up in Queensland and served with the 61st Regiment – the Queensland Cameroons – in New Guinea.

He was playing a match for his regiment in Port Moresby against the 30th Regiment from NSW when he was spotted by former South Sydney player and coach Eric Lewis, who suggested he try out for the Rabbitohs after the war.

“If I get out, I’ll come and see you,” Rayner reportedly said.

Rayner captain-coached Souths to five premierships, represented NSW 16 times and played five Tests for Australia between 1946 and 1957.

Rayner, who was still in New Guinea when the war ended, would never get the chance to play for his home state during his military service.

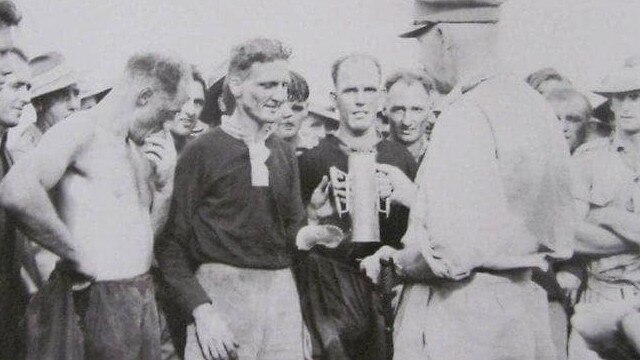

The honour of playing and watching the first “Origin” match went to those who were based in Bougainville on August 21, 1945.

With the war ending 12 days later, the Australian Army was faced with the massive logistical task of bringing its forces – including an estimated 30,000 on Bougainville alone – back home.

“They were pretty much stuck there for months with nothing to do,” Shannon says.

“The American ships took the Yanks home first and the Aussies had to wait for them to come back. The officers were doing anything they could to keep them occupied. There were cricket games, stage shows, Aussie rules and rugby league.”

In true military fashion, everything had to be done by the book, and a Bougainville Rugby League Association was formed, with Brigadier General L.G. Binns, later manager of the Brisbane City Council Transport Department, as patron.

Lieutenant Tom Pedrazzini, a longtime official of the Brisbane Rugby League before the war, was president, and Warrant Officer Ron Connor secretary.

Matches were played on the site of a former US medical company hospital and evacuation centre, renamed Medco Ground.

Throughout the war Aussies from all over the country fought alongside each other without any thought of where they were born or grew up. They were all in it together. But with the fighting over and the men’s time taken up with playing and watching sport, interstate rivalries resurfaced.

Just as their sons and grandsons would 35 years later, the Diggers on Bougainville became frustrated at seeing teams representing NSW battalions fielding players who grew up in Queensland, and vice versa.

The seed of the first Origin series was planted.

Over the years since 1980 there has been much debate and conjecture over who deserves the title, “Father of Origin”.

South of the border, Kevin Humphreys, the NSW Rugby League chief executive of the time, is given credit for starting Origin.

In Queensland, then-QRL chairman Senator Ron McAuliffe is recognised as the man who brought the first series to fruition, and in 1998 The Courier-Mail journalist Barry Dick revealed it was Brisbane Broncos’ founding director Barry Maranta who adapted a concept used by the Victorian Football League in 1977 and presented it to McAuliffe.

Nowhere is the name Arthur Titley mentioned.

In September 1945, Major H.A. “Tiger” Titley, 36, a member of a prominent Charters Towers retail family, was a senior officer on Bougainville.

When Warrant Officer Ron Connor came to him requesting permission to organise an Origin series, he was talking to the right person.

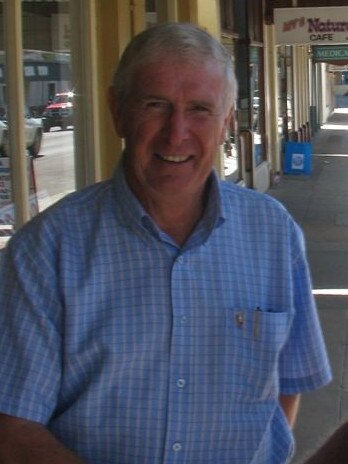

“My father was a real rugby league man,” says Titley’s son Rob, who lives in the North Queensland town, 134km inland from Townsville.

“He played hooker for Rovers club in Charters Towers before the war. That’s when he got his nickname, Tiger. He played his last game in 1962 when he was 53. It was the 50th anniversary of Charters Towers High School and the ‘Old Boys’ played the ‘Really Old Boys’. The busiest person on the field that day was the first-aid man. The only thing he had in his kit was a bottle of rum.”

Major Titley gave the go-ahead for the game and arranged for the 31/51 Battalion band to provide entertainment. Commander of the 3rd Infantry Division, Major General William Bridgeford, commissioned a trophy that was made in the army workshop and selectors from each state started choosing their teams.

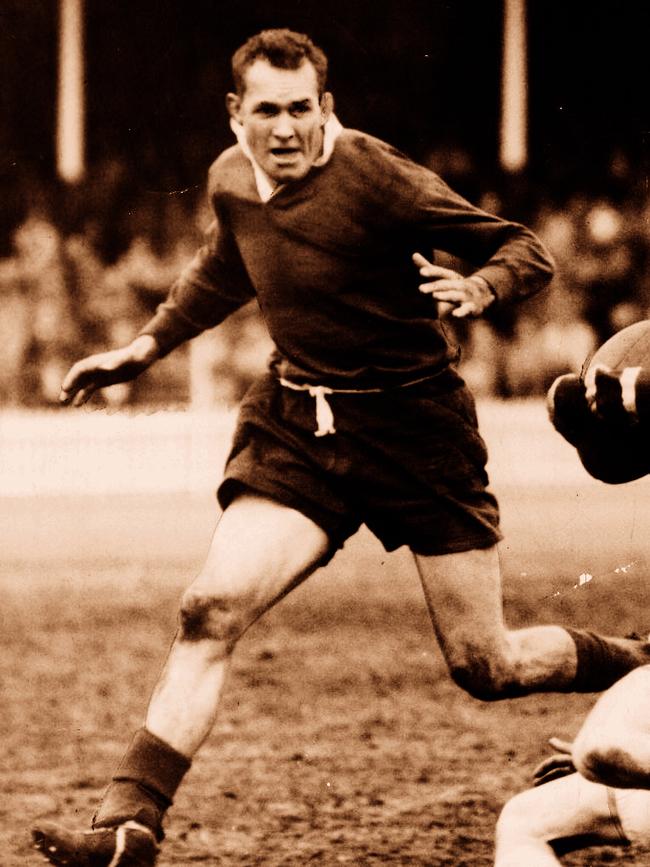

At 1400 hours on September 16, 1945, the Queensland side, wearing maroon jerseys and captained by Rockhampton fullback Jack Barnes, ran onto Medco Ground and lined up against NSW, wearing blue and led by Newcastle five-eighth Horrie Marjoribanks.

There is a certain irony about Marjoribanks captaining NSW. He was the uncle of renowned 15-Test five-eighth Bobby Banks who, though he was born and raised in Newcastle, NSW, played 26 times for Queensland and was part of the 1959 side that was the last Maroons team to beat the Blues in a series prior to Origin.

“I played against Uncle Horrie once,” recalls Banks.

“I was 17. I don’t know how old he was but my dad was the oldest of ten boys. I was playing for Central, he was playing for Wests. He was a wonderful player, a great tackler. I remember when I was in the under-16s watching him play for Newcastle against Wollongong. He was up against a bloke called Johnny Hawke and he played all over him. Hawke got picked in the Country Firsts ahead of Horrie and went on to play for Australia. I might be biased, but I reckon Horrie was hard done by. He could have been the first of our mob to play for Australia.”

The best-known of the Queenslanders was 29-year-old Sergeant Kelly Brennan, who started his career with Ipswich Brothers in 1933 and went on to play with Rialto and West End. A tough, solid hooker, Brennan played 12 matches for Queensland between 1946 and his retirement in 1948.

Other than the names on the trophy and a belief that two matches were played and won narrowly by Queensland, Greg Shannon was initially unable to unearth a great deal of detail about the series, but his lecture stirred interest, leading to a number of discoveries.

While combing through old programs, Shannon found a small story about the handover of the Japanese artillery shell cup to the Queensland Rugby League by the army at half-time in a 1946 Brisbane club match.

The article confirmed that the matches were both won by Queensland – 10-9 and 20-13.

The most valuable breakthrough was by NSW-based league historian David Middleton, who came across an article from Rockhampton’s Morning Bulletin of September 27, 1945. Headlined “Football on Bougainville – Queensland’s win”, it was a detailed account of the first match written by Warrant Officer Connor who, as well as being secretary of the Bougainville Rugby League Association, was one of the Queensland selectors.

Describing the match as “one of the most spectacular and exciting games of rugby league I have ever witnessed”, Connor said soldiers who had recently returned from leave on the mainland rated the standard of play on the island higher than A-grade.

“One man went so far as to say that this interstate match was better to watch than the one played in Brisbane a few weeks previously.”

The teams were, Queensland: J. Barnes (capt), J.Christopher, L. Ashmore, C. King, E. Lade, N. Hoare, R. Williamson, H. Bradshaw, M. Tresedor, T. Kraft, M. Thompson (vice-capt), K. Brennan, F. McLennan.

NSW: H. Parkinson, W. Peachy, D. McRitchie, T.

Briggs, H. Dhu, H. Marjoribanks (capt), R. Miller, H. Taylor, V. Love, C. Smith, J. Hobson (vice-capt), D. Sinclaire, H. Freeman.

Many of the players were A-graders from Brisbane and Sydney. The referee was Brisbane’s Frank Ballard and the game was broadcast to troops throughout the islands by Tom Pedrazzini.

“NSW won the toss and Bobby Williamson kicked off for the Bananalanders,” Connor wrote.

“From the word ‘go’ the Queensland forwards were on the ball and stayed there until the final whistle.”

Winger Jim Christopher kicked two penalty goals and scored a try just before half-time to give Queensland a 7-nil lead at the break.

Midway through the second half, NSW fullback Norm Parkinson kicked two goals to move the Blues within three points and “then kicked a beautiful field goal from about 40 yards. The kick was remarkable in that the ball hit the crossbar, bounced into the air and fell on the right side. Queensland 7, NSW 6.”

NSW then scored a try that Connor described as “the most brilliant of the match”, with centre Doug McRitchie on the end of a backline movement in which “all men from the halfback to the winger handled”.

Parkinson missed the conversion, leaving NSW ahead 9-7 with five minutes to play.

Queensland went on the attack and when Christopher missed a goal with two minutes left, it seemed the Blues were home but as is so often the case in Origin football, the final scene was still to be written.

“The Queensland forwards carried the play to ten yards from the NSW goal line and fierce rucking resulted. Thompson, who was acting as dummy half, gathered the ball and passed to Hec Bradshaw, who smashed his way through the NSW defence, was tackled by the fullback but dragged him over the line to score about 30 seconds before the fulltime bell rang. The spectators swarmed over the field and Hec was carried shoulder-high to the dressing room.”

IN JULY 2012, JOURNALIST MICHAEL Saunders received a phone call in the office of The Northern Miner newspaper in Charters Towers.

It was a woman who said her father had something he might be interested in looking at.

His name was Ernie Hill, she said, and during the war he’d been at this rugby league game. He still had the program ... Michael drove out to Mill St and met Ernie and his wife Mary.

They told him about how Ernie had heard the commentators in 2008 talking about the first Origin and how Mary had sent off a letter to Wally Lewis telling him about Ernie’s program. “I sent it to WIN TV in Rockhampton but never heard back,” she tells The Courier-Mail.

“He’s a busy man, he probably never got it. Then (in 2012) one of our daughters rang the paper and the reporter came out here and we showed it to him. He wanted to take our picture but we were a bit too shy for that. We just thought someone might be interested, that’s all.” The newspaper ran the story and a photo of the program.

Michael Saunders had read a story by The Courier-Mail league writer Steve Ricketts about Greg Shannon’s lecture and sent Shannon a photocopy of the single-sheet program. It is now on display at the National Rugby League museum in Sydney.

Ernie Hill died in February 2013, aged 92.

“He never got to a State of Origin, but he watched every one of them on TV,” Mary says. “He was deaf in one ear after the war and he used to have it up so loud. I think you could have heard it down the street. It didn’t matter where you were in the house when he was watching football, you could hear every word. I think I knew the name of every player in Australia at one stage.”

The TV might be quieter at Mill St these days, but the Hill family interest in State of Origin lives on through Ernie’s three sons, eight grandsons and his great-grandsons. And the family still has the family heirloom, Ernie’s program.

The question has to be asked: why did he keep it all those years?

“Because he loved rugby league, and he loved Queensland,” Mary says.

“It’s not everyone who can say they’ve seen every Origin game ever played, is it? After all those years he couldn’t remember who won that first game but if anyone asked him he said, ‘Queensland, of course’.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Top 10: QLD’s best schoolboy football prospects

A Rocky centre dominating in both codes, an Ipswich Grammar x-factor, a school leader set for the Titans, and the son of gun going to the Roosters. It’s the top 10 of our 50 best schoolboy footy prospects.

The 50: Schoolboy champs making their mark

An Ipswich SHS beast heading to Penrith, a PBC backrower snaffled by the Roosters, and a Downlands kid that plays like Ponga. It’s part four of our look at QLD’s best schoolboy footy prospects.