Why these Olympic heroes are pleading for ‘clear pathways’ for today’s Indigenous athletes

When Patrick Johnson and Nova Peris rose to stardom, there were no clear pathways for the champion Indigenous Olympians. Now, they are creating avenues so young athletes don’t have to go through what they did.

Olympics

Don't miss out on the headlines from Olympics. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When you arrive in this world on a speed boat there’s a fair chance you are born to be fast.

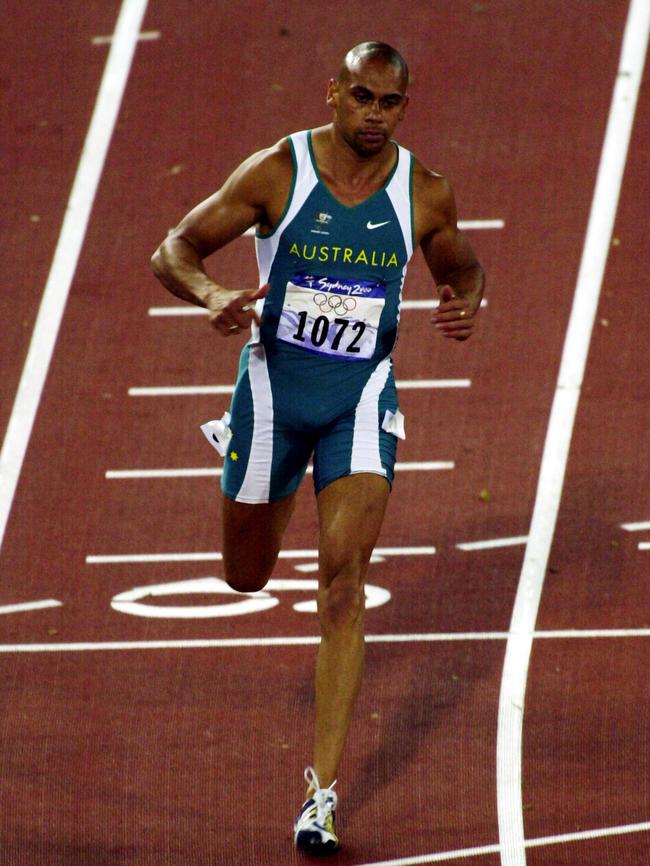

And so it was with Australian sprinter Patrick Johnson, whose mother was on a speed boat haring from the Yarrabah Mission to the Cairns hospital when Patrick popped into the world on September 26, 1972.

Johnson ended up spending the first 17 years of his life on his father’s mackerel trawler after his mother was killed in a car accident when he was two.

He didn’t know what the words high performance even meant until he was 24.

Six years later he spent a year as the fastest man in the world and his 9.93 seconds recorded in Japan 21 years ago for the 100m sprint has never been eclipsed by an Australian male.

It’s an enchanting tale about a boy who had so many reasons to fail but didn’t. Who climbed a mountain despite the system and not because of it.

But Johnson does not want his exotic tale to be the journey of those who follow him. He defied incredible odds but he wants those odds to be on the side of those who tread in his footsteps.

That’s why he was so fulfilled to be part of the launch of the Connect to Country Action Plan in Brisbane designed to smooth high performance pathways for Indigenous athletes in the lead-up to the Brisbane 2032 Olympics.

“You have two worlds coming together,’’ Johnson said.

“Aboriginal people have always had the talent. Why were they not more present in the system? Because they haven’t had a place. We haven’t had culturally safe protocols through the high performance strategy.

“Now we have a place. We are trying to create a clear pathway.’’

Of the 4315 athletes who have represented Australia at a modern Olympic Games, just 60 are known to be Indigenous – it’s a chastening statistic no-one is proud of. Those least surprised by it and the ones who have faced the challenge of beating the odds.

“Because of my passion for what I did, nothing was going to stop me. I was never part of the system. I never did high performance sport until I was 24 years old. At 30 years old I became the fastest man in the world. Why could I not do that earlier? Because I was never part of a system.

“Why doesn’t every kid have a pathway into sport, particularly leading into 2032?

“This is a small stepping stone to ensure Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a place in sport and can feel part of the high performance set-up.

“Yes I am a bit different in that I started a bit later in sport but my question would be why didn’t I have a pathway into track and field very early?’’

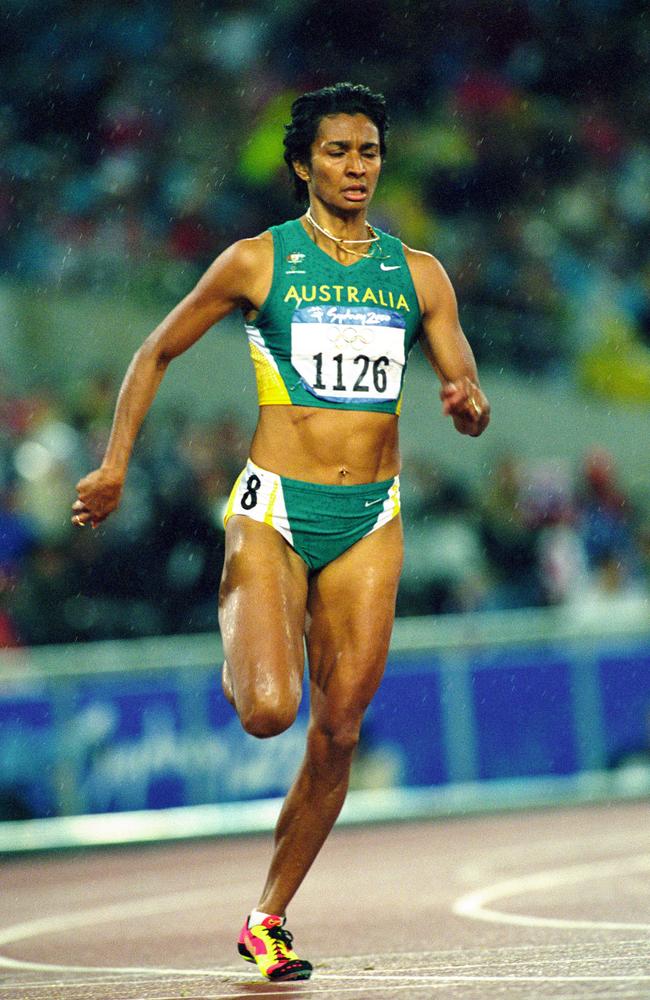

Nova Peris, an Olympic gold medallist in hockey who also made the Olympics as a sprinter, stood beside Johnson at the launch and noted the uniqueness of their stories.

“Patrick was born on a speed boat and I was a mother at 19 – who would have thought we would have made the Olympics?’’ she asked.

Peris has been part of a movement to change the Olympic constitution to recognise the contribution of Australia’s Indigenous athletes.

“I have been in 50 odd countries and people used to ask me which country I was from. I got that a lot,’’ Peris said.

“I would say, ‘I am Australian’’ and they would say, ‘but you are black?’ It was asked of me.

“Australia had no obligation to tell the world there was a first nation existence of 65,000 years prior to 1992. In my sense of getting my head around a lot of stuff.

“My thing is when you go to a country you understand the cultures and the protocols.

“If you are an Australian athlete and you put on the green and gold. You just don’t represent 250 years of history. You represent 65,000 years of history. You don’t get to pick which history you want.’’

Indigenous Olympians preparing for Paris will be given a grant of $5000 towards training and costs.

It’s not a life changing sum but it’s a step in the right direction, as recognised by Lydia Williams, the Matildas goal keeper who will end her 20 year international career after the Olympics.

“I grew up on a single parent income and a had to do a lot of fund-raising,’’ Williams said.

“There us a lot more opportunity for funding for athletes in general now. The recognition of Indigenous athletes in the media is a lot higher.

“But it needs to increase the level American sports have. They shine their lights on Afro-American athletes.’’

It’s a small but telling reminder that while the world is changing it needs to change some more.

More Coverage

Originally published as Why these Olympic heroes are pleading for ‘clear pathways’ for today’s Indigenous athletes