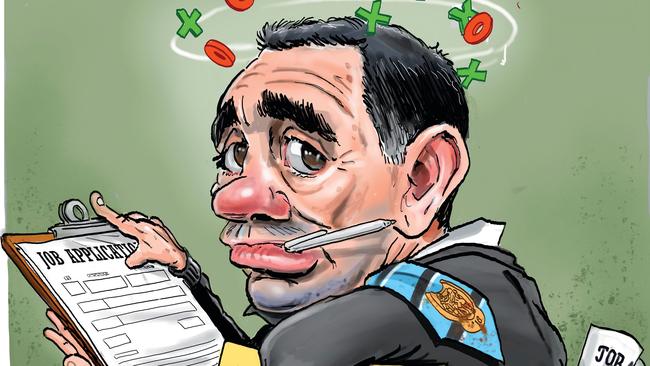

Paul Kent: Why Manly are desperate to end Shane Flanagan’s coaching exile

The Sea Eagles need Shane Flanagan, but there are only two reasons for him to join Manly. The second should have incoming coach Anthony Seibold nervous, PAUL KENT writes.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The greatest problem for Shane Flanagan, it seems, is that he keeps getting up when people believe he should stay down.

He won’t stay away, which many consider to be the polite response.

Flanagan has been in the thick of it again this week.

Anthony Seibold is attempting to save his career, his last shot by taking over Manly, and the first big business he does is try to lure Flanagan to be his assistant.

He knows the value Flanagan still has as a coach.

It carries a deep irony, though.

As much as Flanagan is trying to find ways to revive his career, so is Seibold.

And the difference between success and failure for the new Manly coach might not be so much what he has learned since being sacked at the Broncos, one of the more spectacular crashes in recent times, as it might be the man about to be alongside him.

Flanagan is set to join Manly as one of Seobold’s assistants.

Within the club Flanagan is regarded as an essential part to helping Seibold succeed.

If so, why not appoint Flanagan as the head coach?

It is confusing.

The question might more be why can’t Shane Flanagan get a job?

It is not yet Christmas but already four coaches have been sacked this year after Des Hasler was tossed out at Manly a week ago.

Manly’s problems are not as severe as they are at Wests Tigers, Canterbury or the Warriors, yet Flanagan did not get a proper look in at any of them either.

Canterbury has hired the latest Next Big Thing and anybody that has come across Cameron Ciraldo is certain he will be a successful long-term coach.

The Warriors have gambled somewhat more, hiring another Penrith assistant with impressive credentials in Andrew Webster.

But the gold medal goes to the Tigers, who have appointed Tim Sheens for two seasons before the rookie Benji Marshall takes over and attempts to turn water into wine.

Against that, Flanagan would look a safe bet.

To be fair, Flanagan had a bit to come back from: caught cheating while he was suspended for cheating.

The first for his role in Cronulla’s peptide scandal, the second for communicating with the club while he was supposed to be serving his suspension for the peptide scandal, which was forbidden.

There is plenty of nuance around each — mitigating circumstances that sway you either way depending on your persuasion — but that is the guts of it.

Spark a conversation around it and it soon becomes messy.

One argument being, what is the point of any punishment if we don’t believe in redemption at the end of it?

Flanagan has served his time, and continues to do so.

There are only two reasons Flanagan should even consider taking up Seibold’s offer.

It puts him back on the tools, firstly, in what is probably the last honest area of coaching. No contracts or managers to worry about, no salary caps or sponsors.

The second is less positive, but sits him over Seibold’s shoulder to wait patiently until Seibold fails and where he is in prime position to take over.

What he would learn from Seibold, in comparison to what he would provide, is questionable.

Flanagan is one of the best coaches around the NRL and without doubt the best NRL coach currently without a job.

What he did at Cronulla was close to remarkable.

He took over the Sharks near the end of the 2010 season when they were 14th and without hope.

In his second full season he got the Sharks to the finals, missed the 2014 season because of his first suspension, and in 2016 took the Sharks to their first and only premiership.

He lost the job when he was deregistered for his second offence.

Go back as far as you like and there are few coaches capable of taking a team from near the bottom of the ladder all the way to a premiership, especially without an overarching club figure also involved, which Flanagan never had at Cronulla.

Yet he did, assembling the roster and coaching the team to premiership success.

But Flanagan has been back for three seasons now, eligible to coach, and despite 11 coaches at nine clubs sacked within that time, Canterbury and the Warriors managing it twice, he has failed to get a start at them all.

He keeps being overlooked.

So much that Seibold, one of those coaches sacked since Flanagan has been available, rissoled from the Broncos just two years ago, has leapfrogged him into the Manly job.

Why he would join the Sea Eagles is one of those weird ironies only the NRL regularly offers.

Flanagan is currently running the roster management at St George Illawarra where the praise has been enormous.

Against that, nobody needs to be reminded that Dragons coach Anthony Griffin has moved to the front of the line in the coaching target shoot and needs a strong start to next season to save his job.

You would assume Flanagan is primed to step in.

Why sacrifice that to take a similar place at Manly, where the coach has longer job security?

Manly briefly considered Flanagan before ruling him out. Too much like Hasler, they settled on, wanting to micromanage everything.

They believed it was the wrong fit for the playing group.

The thinking goes that Manly has always had a strong senior playing group which could handle the tough coaching under the likes of Bob Fulton and Hasler.

But this group is different. While the likes of the Trbojevic brothers and Daly Cherry-Evans and several others can handle the tough coaching there is also a large posse of young players coming through, predominantly Polynesian, who would respond better to a more modern style that Seibold presents.

The Sea Eagles can explain Seibold’s failure at Brisbane by the lack of a senior figure like he had in Shane Richardson at Souths.

The job was too big for him at Brisbane, and Manly believes Seibold has learned the mistakes from that. Certainly he lost his way, and by the end he was a vastly different man to the one that walked into the job.

If he carries any of the baggage from that stint, though, it will end the same way.

That’s why Flanagan is so wanted at Manly, to assume a guidance role like Richardson was at Souths to help Seibold through when the realities stray from rugby league theory.

It makes Flanagan more right for Manly than Manly is right for him.

It makes Flanagan right for a lot of clubs, yet they continue to overlook him.

* * * * *

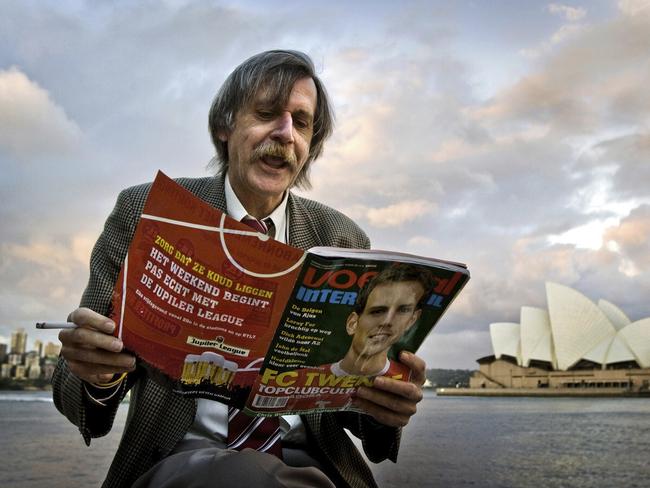

THE thing about Peter Kogoy, the sports journalist who died last week, was that he was always kinder to others than he was to himself.

He came from an era when journalists were expected to be misfits and drunks, and he was more than adept at both, but it was also a time from when journos protected their contact book heavily and would refuse to give even a colleague a break.

My first day on the job Alan Clarkson refused to help me with a number for North Sydney secretary Bob Saunders, for instance, saying he didn’t have one. No big deal, it’s the way it was, but Kogoy was happy to provide and was always at my desk offering help.

That said, sitting with Kogoy was a health hazard, for various reasons.

Several years before my stint, when you could still smoke at your desk, Kogoy would have one and often two cigarettes burning while he pounded out a story which, after a while, began to send Tony Megahey at the desk next to him crazy.

Finally Megahey had enough and went to a joke store and bought three exploding cigarettes which he discreetly pushed into Kogoy’s cigarette packet.

Everyone in the office was in on it and when Kogoy returned to his desk and pulled out a bunger everybody tensed, waiting for the explosion.

Nothing happened, he lit up and puffed away.

Soon after he reached for another and everybody crouched a little lower in their chair …

Nothing.

About 10 minutes later he yelled an expletive and jumped to his feet, grabbing his jacket and heading out before pivoting and grabbing his cigarettes.

“I’ve got an interview with the adoption agency,” he said.

They did try to stop him, but Kogoy was gone. The interview was one of the last stops before adopting his son Daniel, and it didn’t begin well.

“I’m a little nervous,” he finally told the interviewer, “do you mind if I have a cigarette?”

When the interviewer climbed back up from under his desk, feathers and whatever else fluttering down, the interviewer looked at a stunned Kogoy in front of him, the butt of the cigarette still in his mouth, and took out his pen.

“Of course Mr Kogoy,” he said, “I will have to note that you’re somewhat of a practical joker.”