Greg Inglis’s decision to enter a mental health clinic will help others seek help too

GREG Inglis isn’t only helping himself by entering a mental health clinic, he’s unwittingly doing what he’s done ever since he entered the NRL - helping others.

NRL

Don't miss out on the headlines from NRL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

INSIDE the ANZ Stadium dressing room, with his anterior cruciate ligament severed, Greg Inglis looked up at South Sydney coach Michael Maguire and nodded.

Not one person inside that room was surprised. Because has anyone ever witnessed Greg Inglis say no?

It was round one in March of this season and the Rabbitohs champion had suffered a knee injury that would render the next six months of his footy career useless.

The chance to play another Anzac Test match in the green and gold with his old mate from Melbourne and Queensland Cam Smith, gone.

The chance to appear in an inspiring 31st State of Origin match for the Maroons this series, forget it.

A shot this year at reaching the magical milestone of 300-NRL games, destroyed.

But Inglis never once contemplated calling it a night.

So out he went, hobbling — now infamously — on the wing with the cartilage inside his knee ripped and shredded.

Justifiably, the Rabbitohs coaching staff were pilloried by TV commentators and fans on talkback radio for the lack of authority shown by leaving the two-time premiership-winner, Clive Churchill medallist and Golden Boot winner to hobble and tackle with a season-ending injury.

But Inglis, being the Inglis few know of whom never wants to disappoint, was always going to need to be dragged from the field.

When Inglis was still 21 and the Melbourne Storm were charging towards the 2008 minor premiership, his father Wade required life-saving heart surgery at the Royal North Shore Hospital.

Wade suffered the heart attack on a Saturday.

His talented son needed to play for Melbourne and beat South Sydney on the Sunday to help the club secure the minor premiership.

Inglis didn’t hesitate. He booked a flight to Sydney to stand by his father’s bedside and was willing, upon return, to catch a taxi directly from Tullarmarine to Olympic Park in his playing strip if he had to.

“For him to travel up before the game against Souths to be with his family last week makes me very proud,’’ Wade told The Sunday Telegraph at the time.

“That’s what he’s like though. He loves his family greatly.’’

Be it his family or a powerful social media call for fans and players to respect homosexuality within the game in 2012, to choosing Father’s Day in 2015 to reveal he was the father of a secret son, Inglis has made very public decisions almost always for the benefit of others.

“If individuals want to come out and promote that they’re gay or they’re not, I’m all for it,” Inglis said.

“I’m a big believer, a firm believer, in respecting what others are and who they are.’’

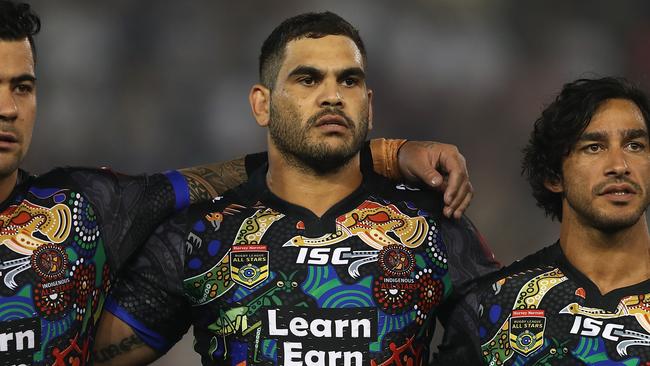

There was also this public mission statement, ahead of the NRL’s Close the Gap round, back in 2014.

“By the time I leave this earth I want to see a big change in indigenous health,’’ Inglis said.

“I am not afraid to voice my opinion about indigenous culture.

“It is vitally important to raise awareness of what the true understanding of Close the Gap is, and that is closing the gap between the indigenus and non-indigenous health.’’

What led Inglis to recently check-in to a mental health clinic isn’t so simple as a few tight paragraphs in a newspaper. But it appears, at the very least, one of the greatest rugby league players to have ever played the game, has put his hand up to get help and to do what he should have done back in March — put himself first.

The knee injury is a major factor, but not the only contributor to his clinic admission.

Not since making his NRL debut at the age of 18 with the Melbourne Storm has Inglis suffered an injury so devastating.

What is known to those within the Rabbitohs’ inner-sanctum is that he has felt disconnected from the NRL squad, unable to find purpose in waking each day without being able to offer his greatest strength — himself — to the struggling football team.

At 30, Inglis has also allowed his mind to wander down the path almost every footballer takes, of what life could be like without rugby league in it.

As Justin Hodges, his closest friend both in and out of the game, explained this week, Inglis feels “lost’’.

That safety-blanket of rugby league is the reason, too, that Inglis remained in Sydney, when his wife Sally recently moved out of their Sydney home to Queensland to be closer to family in Brisbane.

The shift north to visit family isn’t, for Sally, an unusual move as the winter chill hits Sydney, but this time Inglis felt that given he was injured, he owed it to South Sydney to remain active in an assistant coaching role that they had offered him.

News of Inglis’s admission to a mental health facility has rocked the NRL.

It’s an extremely personal decision, which has gone public.

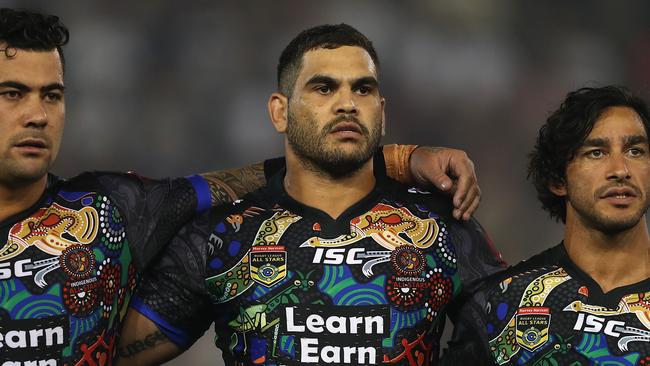

It’s a decision his Queensland friend Johnathan Thurston says will prove a catalyst for other players seeking help when they face their own injury demons.

And so this time Inglis isn’t only helping himself, he’s unwittingly doing what he’s done ever since he entered the NRL, he’s helping others.