Craig Polla-Mounter, Paul Carige and the greatest Bulldogs-Eels game ever played

TWENTY years since Canterbury and Parramatta played one of the greatest matches of all time, NICK CAMPTON looks back at the epic 1998 preliminary final.

NRL

Don't miss out on the headlines from NRL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

EVERYONE who saw it remembers.

Even people who didn’t see it can never forget.

Parramatta and Canterbury have one of the most storied rivalries in rugby league and when their story is told it’s dotted with legendary names.

Sterling and Mortimer, Kenny and Hughes, Gibson and Ryan, Ella and Lamb, Price and Langmack.

They’ll live for as long as the game is played.

SUTTON: How Bra Boy got kicked into line

SPREE: Roosters could land Brett Morris

CRAWLEY FILES: The Jarryd Hayne question

OUT: Eastwood to depart Canterbury

So will Paul Carige. Nobody will ever forget Paul Carige.

Twenty years ago, Carige, a rangy fullback with a good turn of pace and the ability to break a tackle, experienced one of the most disastrous afternoons in rugby league history. In fact, it wasn’t even an afternoon. It was about 25 minutes.

Paul Carige dragged Parramatta through a 25-minute hellscape against their fiercest rivals that went on to define an era for the Eels and pitched their fans into a pit from which they are yet to truly escape.

PART ONE: LOVE AND CARIGE

The first season of the National Rugby League was more fractured in hindsight than many may think. Not only were the wounds of the Super League war still raw, barely healed at best; the league was intent on reducing the competition from 20 teams to 14 in 2000.

Merger talks dominated the background of the bloated competition with targets firmly on the backs of Sydney clubs.

The cull went by a bloodless name — “rationalisation” was the euphemism of the day — and deals were made and broken as the game began to shape its future.

Whatever form that future took, Parramatta seemed certain to be a superpower within it. After their last premiership in 1986 the Eels missed the finals 10 years in a row. The final humiliation came in 1995 — Parramatta finished 19th out of 20 teams, winning just three games.

Coach Ron Hilditch somehow survived the year and took the team to 13th the following season before he was replaced by Brian Smith.

A meticulous coach who would search for any edge, no matter how small, Smith rebuilt the Eels from the ground up.

Part of the club’s rise from the depths of 1995 was on the back of “the Canterbury Four” — Dean Pay, Jason Smith, Jim Dymock and Jarrod McCracken. The quartet had turned their back on the Super League contracts they signed with the Bulldogs to stay loyal to the ARL. Parramatta was deemed a suitable home, and from this once-a-decade boon of top tier talent, Smith built a contender.

After breaking their finals drought in 1997, the club made the top four in 1998. The Canterbury Four were joined by young guns like Nathan Cayless, Clinton Schifcofske and Nathan Hindmarsh and journeymen come good, the kind of players Smith could always shake the dust off, like Mark Tookey, Shane Whereat and Stuart Kelly.

Super League tore Canterbury apart at the seams. The defection of their four star players, three of whom were part of the miracle premiership of 1995, ripped the heart out of the club. Perennial contenders through the 1990s, the civil war years were difficult.

They finished 10th in 1996 and a fourth-placed finish in 1997 flattered to deceive — the Bulldogs carried a meagre 10-8 record in the rebel league.

Most of the heroes of 1995 were gone or on the verge of retirement. Coach Chris Anderson, one of the club’s favourite sons, left at the end of the 1997.

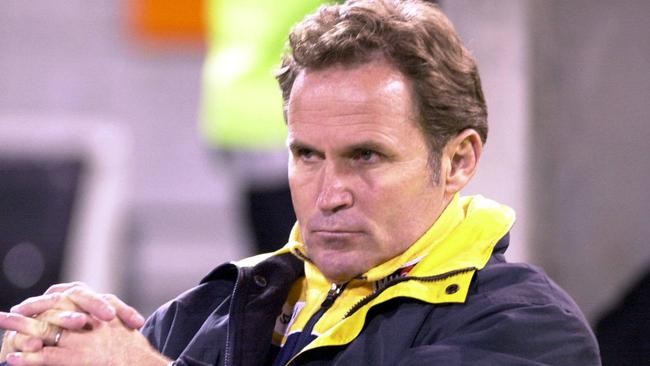

Because this is the family club, they promoted from within with former premiership-winner and hard-nosed forward Steve Folkes taking over for 1998.

That season, the Eels quickly established themselves as premiership material. Smith’s methods were now part of the fabric in his third season, their core of Dymock, Smith, Pay and McCracken were all between 26 and 29, their prime football years.

The talented but inconsistent John Simon was as good an answer as any to the Peter Sterling Curse and the club spent much of the season in the top four.

They even pulled off a win over mighty Brisbane, dealing the Broncos one of their few regular season defeats.

Finishing in fourth place after 26 rounds, the Eels were a dark horse for the title.

For the Bulldogs, the whole year was helter-skelter.

They dropped four matches in a row after winning their season opener and had just four victories over finals-bound teams all season.

Despite a one-off 10-team finals series making room for any team with a skerrick of talent they needed to win their last four games to sneak into the playoffs in ninth spot.

The last two, an 8-4 win over Anderson and Melbourne in a Belmore monsoon in the final game at the old ground for more a decade, and a 25-24 triumph over the Steelers were special efforts.

But they looked to be fodder for the real contenders. Making the finals was as good as they were supposed to hope for.

It is in the finals where our story truly becomes something special. In the awkwardly named Major Preliminary Semi Final, the Eels knocked over fifth placed Norths 25-12 after looking in control the whole time.

Then, in a massive shock, they beat Brisbane, again. The Eels went to ANZ Stadium and handed the Broncos their first loss since Round 13 — which doubled as the last time the two teams met. Fifteen of the 17 Broncos who took the field had played Test or Origin football.

Parra did them anyway, with their swarming defence and excellent ball-control slowing down Brisbane’s brilliant attack.

Pay and Kelly nabbed the tries with Ian Herron, playing his only game of the season, kicking two touchline conversions before a John Simon field goal capped a 15-10 victory.

Of particular note was Carige — he was safe as a bank at fullback and produced an incredible tackle on Michael Hancock to save a try and possibly the match, playing well enough to earn 1998’s highest honour, an invite to The Footy Show the next week.

Looking back at the footage now, Carige is a typical footballer — understating the magnitude of what he’d done, terming his incredible tackle on a tryline-bound Hancock in the 74th minute when Parra led 13-10 as something that just happened, just a thing he did.

“I don’t know, I’m just glad I was over there in position and lucky I grabbed hold of him.”

Sterling was much more lavish with his praise.

“I tell you, this is one of the best tackles you will see all season. From three metres out he is going to go through anybody.”

Paul Vautin deemed it “the tackle of the century”, Sterling chimed in it could be the tackle of the millennium.

Carige gracefully gave strength and conditioning coach Ashley Jones a rap and the conversation turned to high balls, of which Carige had taken three against Brisbane. Defusing bombs was regarded as Parra’s main weakness at the time.

“We work on it, week in and week out.” Carige said.

“It’s a bit of a lottery, the high ball, at times. Some are uncatchable.”

Watching it now is excruciating. Carige had just had perhaps the best moment of his career. He was being showered with praise by one of Parramatta’s best ever players, certainly their most famous.

He had no idea what’s coming. How could he? Nobody would be cruel enough to predict what lay in his future.

The Eels had a week off before the prelim final, where they’d meet the winner of Newcastle v Canterbury. They had the reputation of being the Bronco hunters, Wayne Bennett’s kryptonite. Life was good.

PART TWO: A FORGOTTEN CLASSIC FOR THE BULLFROG

Canterbury came so close to not being in the finals at all. If they didn’t knock Illawarra over by a point in the Steelers’ last ever clash as a stand-alone club, their spot in the finals would have gone to Cronulla.

It was not a win without controversy either.

Referee Steve Clark “changed his mind” on a knock-on call according to one match report.

Clark signalled for a knock on when Bulldogs forward Troy Stone appeared to lose the ball in a tackle with Craig Wilson.

The loose ball was scooped up by Glen Hughes for a controversial try.

Replays showed John Yard made the correct call, but Clark’s decision-making was criticised. “We just relaxed when he said knock on,” said Steelers star Trent Barrett.

Craig Polla-Mounter kicked a field goal in the final moments to deliver a win and a finals berth to the Bulldogs, but Folkes wasn’t impressed.

After the match he claimed the Dogs wouldn’t go anywhere in the finals on current form.

In the minor preliminary semi-final, or 8th v 9th in layman’s terms with the losing team going home, the Bulldogs took on the Dragons and pulled off a 20-12 victory, again in controversial circumstances and again with Clark as the referee.

After Saints got out to a 12-0 lead at Kogarah, the Bulldogs struck through Daryl Halligan, but a pass from Jason Hetherington in the lead-up was clearly forward.

Likewise, when Rod Silva plunged over off a Darren Britt pass shortly thereafter, there were doubts he made it to the line but Clark opted not to use the video referee.

Rookie centre Shane Marteene scored the match-sealing try in the 74th minute and the win turned unsavoury when Clark was spat on by a member of the crowd and needed a police escort for him and his family to leave the ground.

With memories still fresh of 1995, when the Bulldogs won the comp from sixth spot in a finals run that also began with a win over the Dragons, there was a strong mythology regarding Canterbury’s post-season prowess.

“There were a lot of parallels to that game in ’95 weren’t there?” Terry Lamb, captain of that ‘95 side and then reserve grade coach, said after the match.

“A few of the blokes were around then, like Britty and Polla, said it was a similar sort of feeling.

“That’s what I felt as well, but we can’t get carried away with it; we’d still have to win three more games to even get there.”

In 1995 the team were driven not only by Lamb’s retirement, but by the ill-health of club patriarch Peter “Bullfrog” Moore.

Moore was once again struggling after suffering a stroke and throat cancer. The man was the lifeblood of the Bulldogs for over a quarter of a century. What Ken Arthurson was to Manly and Nick Politis to the Roosters, so was Moore to Canterbury. The Hughes brothers of the 1970s and 1980s, Garry, Mark and Graeme, were his nephews. Three of Garry’s sons, Glen, Steven and Corey, played for the club in the 1990s and 2000s. Chris Anderson and Folkes married his daughters. The Moore and Mortimer families were what made Canterbury the family club.

A 23-2 smashing of a weary North Sydney followed the next week for the Bulldogs, the easiest victory of Canterbury’s run. The Bears were finals contenders throughout the 1990s, but this was the end of their time as a top shelf team. Too many players had been through too many battles and the Dogs hustled the life out of them.

The main news from the match was Polla-Mounter suffering a chipped bone in his back, putting him in doubt for the elimination preliminary final against the Knights.

It was against Bulldogs club policy at the time for players to receive painkilling injections and in the end it was too much for Polla-Mounter — he was out, Glen Hughes was in, partnering his brother Corey in the halves.

History recalls Brisbane as the unstoppable giant of 1998, but the Knights were just as dominant.

Like Brisbane, they recorded just five losses in the regular season and, like Brisbane, they crashed to a loss in the first week of the finals after giving up a 15-0 lead to Sydney City to go down 26-15.

Newcastle’s premiership heroes of 1997 — the Johns brothers, Paul Harragon, Bill Peden, Mark Hughes — they were all there. A young Danny Buderus was starting his third match at hooker. Robbie O’Davis and Adam MacDougall were missing due to drug suspensions, but this team was still red hot.

Future events would overshadow Canterbury’s 28-16 win but for any other team it would have been a highlight of the season. Matthew Johns put Brett Grogan over early before Andrew Johns set up tries for Jason Moodie and Mark Hughes for the Knights to lead 16-0 after 28 minutes. But as they did so many times, the Bulldogs rose again.

Glen Hughes, an inconsistent player who had earned the ire of Canterbury fans through the season, started the fightback when he threw a dummy and scored just before half-time. Halligan chipped away with penalties in the second half before Hughes flew on to a ball from Travis Norton to find space in the 69th minute.

Hughes had his brother Corey in support, and the rookie halfback crossed under the posts to level the scores. Extra time of the non-golden point variety was required, with the teams playing 10 minutes each way.

It took 12 minutes for the deadlock to be broken and it was the towering Britt, the Bulldogs skipper and a giant of a man, to do it. The big prop only scored 12 tries in his 227 first grade games, but none were more important than this — and perhaps none were fancier, with Britt putting a dummy and pirouette together to touch down under the crossbar.

Moments later they were over again — the ball flew through six pairs of hands in a spectacular effort that ended with Silva touching down. The Bulldogs had won 28-16, the papers called it the game of the year.

“We weren’t ready to throw it in at half-time,” Folkes said afterwards.

“We thought the longer the game went, the stronger we would be.

“I’m proud of the boys and we fight on.”

Folkes went on to call the win the gutsiest victory he’d been associated with as a player or a coach.

It was here that the veteran experience of men like Britt proved crucial.

“We can’t celebrate too early,” the skipper told The Australian’s Greg Prichard.

“We made that mistake in the 1994 finals series. We’ve won a few games, but we’ve still got a bit of work to do. Hopefully we can celebrate in a couple of weeks.”

As the dust settled it came out that Moore had addressed the team before the match, urging them to win and telling them he’d already booked his grand final tickets.

“We love him,” Britt told The Daily Telegraph’s Jeff Dunne.

“He’s doing it tough at the moment. To get him out of his sick bed to come to watch just to wish us all luck before the game shows a lot of guts and how me he loves the club and loves the players.”

PART THREE: ONE MORE TIME

After all manner of minor preliminary and major preliminary elimination finals, the convoluted 10-team finals system spat out four sides battling it out for grand final glory.

On the Saturday afternoon, Brisbane hosted the Roosters at ANZ Stadium.

The Broncos had steadied since their shock loss to Parramatta, handing Melbourne a 30-6 belting to salvage their season. The Roosters had beaten the Storm and Knights to set up the blockbuster clash.

The on Sunday the team of destiny would take on the budding powerhouse at the Sydney Football Stadium. The old rivalry of a decade before was to be renewed, with a grand final berth on the line.

Parramatta were firm favourites to progress to their first grand final since 1986 — the week off since their win over Brisbane was supposed to have them refreshed and renewed while the Bulldogs had been through three sudden death finals in a row. Folkes told his charges during the week “fatigue is only a state of mind”.

The full extent of Canterbury’s remarkable run was thrown into the spotlight. Silva didn’t play first grade until Round 17 after off-field tragedy and on-field struggles saw him plummet to the Metropolitan Cup to start the year.

The third tier competition was also the home of centre Willie Talau, who started the season with the Moorebank Rams and was on a contract worth just $2500. He was still working as a roof tiler to make ends meet until the eve of the finals.

Outside backs Gavin Lester and Shane Marteene had both played less than 30 matches. Halfback Corey Hughes was a rookie about to play his 14th top grade game who still lived at home and worked full-time for Bankstown Council as an apprentice carpenter. Travis Norton had joined the club from the South Queensland Crushers the year before and Tony Grimaldi was bound for England once the season ended because no NRL club had offered him a deal.

These battlers were supported by players like Polla-Mounter, Glen Hughes, Jason Hetherington and Daryl Halligan, who had been through the semi-final campaigns of 1994 and 1995 and knew what was required when the whips were cracking.

Moore was at the centre of the build up.

Despite stepping down as chairman several years before, he was still at the heart of the Bulldogs.

Speaking through tears of pride to The Australian’s Greg Prichard from his hospital bed, Moore said the players should play for themselves, not for him.

“They owe it to themselves, not to me or anyone else,” he said.

“They owe it to themselves because of the effort they’ve put in. They have made it this far because they want it.

“They want it so badly. Now they are getting close to the chance to walk off with a tremendous personal achievement.

“It has helped me, watching them do what they’ve done, but I will be proud of them no matter what happens on Sunday.

‘The thing is, though, I know they are capable of going further if they can get an even bounce of the ball. It’s inside them.”

Carige got his share of press in the lead up — he revealed he relaxed before games by watching Video Hits, which is the most 1998 thing I have ever read.

The rangy Queenslander ran through his pre match preparation with The Daily Telegraph’s Tim Prentice and much of it was around diffusing kicks.

“I’ve got a few key words scribbled on my wrist that help keep my mind on the job. You know the sort of stuff — ‘Langer grubbers’, ‘Johns 40-20s’ and so on.”

Carige said he was unfazed by the prospect of copping an aerial assault from the Bulldogs and revealed he considered quitting rugby league at the end of 1996 after he was cut from Illawarra.

“But Brian Smith called me and invited me to trial with the Eels,” he said.

“Things have gone pretty well for me ever since and I’m contracted here until the end of next year.”

He would play just one more NRL game.

Tellingly, Paul Kent’s column that week detailed the four players who could win and lose the preliminary finals for their teams.

Darren Junee and Wendell Sailor were the men most likely for Sydney City and Brisbane, while Carige and Glen Hughes were nominated for Parramatta and Canterbury.

“Paul Carige is called Dr Strangemind and plays accordingly. The nickname is self-appointed, which just might say it all,” Kent wrote.

“Dr Strangemind can field a ball and 50 or 60 metres later be putting down under the posts, bewildering tacklers in his wake.

“He is also capable of dummy-half knock ons, heart-attack passes to his winger/fullback, depending on where he was playing, and of flirting a little too closely with the sideline.

“He paints his hair yellow, or orange, or green, and his excitement rate is high. Nobody knows what might come next.”

Kent then detailed the best way to get at Carige, who was slated to line up at fullback: “Carige will be left to his own, the idea being that with so much time to think, he will create his problems himself.”

Brisbane were the first team through to the grand final. A 46-18 thrashing of an exhausted Sydney City put paid to any wishes of an all-Sydney grand final. Darren Lockyer scored a hat-trick. The Broncos looked unstoppable.

Commentating for Channel 9, Steve Roach was heard to say he didn’t care who won the following day because they weren’t going to beat Brisbane.

PART FOUR: ”THEY LED BY 100 WITH 10 TO GO!”

At last, Sunday came and for 70 minutes, the match was nothing particularly special.

It was tough and hard and fast, the way all semi-finals are, but it wasn’t an epic. It wasn’t the stuff of legend.

Shane Whereat, a former sprinter who was counted as rugby league’s fastest man, opened the scoring for the Eels when he raced on to a Dymock kick. The crafty Dymock and his backrower partner Jason Smith were Parramatta’s best, along with Pay.

A break by young forward Dallas Weston led to a try for Schifcofske, returning from injury on the wing, later in the first half.

In the 62nd minute, Jason Hetherington tried to plunge over from dummy half to finally get the Bulldogs on the board, but lost control of the footy. From the 20-metre restart Dymock linked up with Whereat again and he raced away to score under the posts. It was 18-2 and the blue and golds were dancing.

By no means had Canterbury not turned up — they competed and gave all they could. Parramatta were just more focused, more cohesive, more disciplined.

“To get out of this one would be superhuman.” said Peter Sterling in commentary in the 66th minute.

The Eels could have wrapped it up. Two tries went begging through poor execution. In the 68th minute John Simon kicked out on the full, putting the Bulldogs on the attack. Glen Hughes forced a dropout with a grubber, giving Canterbury their first repeat set of the match and in commentary Channel 9’s Ray Warren threw to Steve Roach on the sidelines for a look ahead to the grand final.

“One thing Parramatta’ll have on their side is the crowd. Everyone will be supporting them next week,” Roach said.

“They will go in with, I imagine, a reasonable level of confidence,” Warren replied.

The next set, that’s when it started. The 69th minute, down 18-2, that’s when it began.

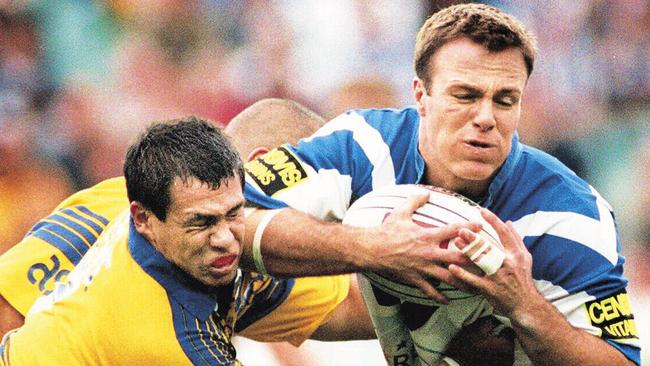

Hetherington, who had toiled hard all day, ducked down a narrow blindside on Canterbury’s left, drew in Simon and put Polla-Mounter through a hole to score.

The pass was forward — of that, there is no doubt. But what did it matter? The game was over anyway.

Halligan rushed the kick and missed it. The Kiwi superboot missed just 17 goals all season, going 116/133 for a success rate of 87.22 per cent. It was, quite possibly, the greatest goalkicking season in rugby league history. But he missed this one.

A desperate attack on the next set fell through when Talau had an inside ball intercepted by Whereat. Simon set for a field goal, to ice the game. He was a field goal specialist, John Simon.

He’d already kicked six that year, including one-pointers in Parramatta’s last three matches. Field goals, like everything else with ball in hand, were easy for John Simon. He had never played in a grand final before, falling short in the final hurdle with Illawarra in 1992. Perhaps he had never risen to the heights to which his talent could have taken him, but here was his chance, now, to win the game, to progress, to prove he could be the heir to Sterling’s still vacant throne.

But Canterbury charged it down. It was a valiant effort, but a futile one. After all, it sucked more time form the clock. In the 72nd minute, Simon had a shot, from point blank range. Twenty out, right in front.

No pressure. Simon missed it. He could have kicked it with his eyes closed, but instead pulled it to the left.

Before the 20-metre restart even took place, Simon was off the field, hooked for David Penna.

On the fourth tackle, unheralded backrower Robert Relf charged on to a Polla-Mounter inside ball across halfway.

He drew in three men and slipped a deft offload to Silva. Relf was an honest, tough player. Flick passes were not often his go, but it was on this day.

Silva exploded into space like he was shot out of a cannon, heading directly for the corner and making it just as the cover arrived. 18-10, kick to come. Six minutes left.

Halligan learned from his mistake, as the great kickers always do. The best kickers, the real legends of the tee, you never see them miss from the same spot more than once in a match. Those same kickers say that this scenario, a sideline conversion in the final minutes to win or tie or keep a game alive, this is why they start kicking in the first place.

This time Halligan swung it right to left and it held it’s line. 18-12, 74th minute.

With renewed vigour and desperation, the Bulldogs ran the Eels ragged. On replay, it seems clear Parramatta were hoping for the time to run itself out. Canterbury, as their coach told them, learned fatigue was only a state of mind.

“They’re throwing the ball around as though tomorrow doesn’t even exist!” rumbled Warren.

A penalty for a strip, and a dubious one at that, put the Bulldogs on the attack. On the fourth tackle they spread the ball wide, all across the backline. Hughes went to Silva, Silva drew in Parra centre Karl Lovell and went to Talau.

Talau, the Metropolitan Cup man himself, burned Whereat to dive over in the corner, mere metres away from where Polla-Mounter and Silva had touched down.

“Parramatta are walking! Now, Halligan from the touchline to level!” bellowed Warren.

Sterling said before the kick was taken that he thought they were going to extra time. Such was the confidence rugby league had in Halligan, the modern kicking master.

He never kicked better than he did in 1998, but he had never had a kick quite like this.

“Has there been a more important kick for Darryl Halligan? Has there been a more important kick for Canterbury?” Warren asked.

Halligan’s strike was clean, but initially it looked as though it would hook across the face of the posts.

At the moment it seemed certain to swing wide, it stayed inside the left post as if magnetised. The ball dropped over for one of the most remarkable goals ever kicked.

In one of the best calls of his career, Warren promptly went berserk.

“He hits it, if it hooks … it’s…..it’s ….IT’S STAYING ON THE LINE! HE’S GOT IT! OH THE MAN, THE MAN IS A MESSIAH! I thought it would hook! But it went straighter than he’s ever kicked it! Halligan has saved Canterbury!”

Vautin screamed that Halligan was a freak. Sterling, in a far more subdued voice, said it was unbelievable and he was right.

Unbelievable is the most overused word in sport, but the way the ball went through the air did not seem physically possible. 78th minute. 18-all.

Now the chance was here for the truly outrageous, to win the game in regular time. Canterbury would have one set against a Parramatta team who were so stunned they could barely go through the motions of the final 60 seconds.

Polla-Mounter was tackled on the fourth, leaving it up to Glen Hughes to take a field goal shot from 45-metres out. It never got off the runway. And then the dawning of the nightmare truly began, the spiral that cost a man his career and the Eels the match.

As the ball trickled down to the dead ball line, Carige ground it with a foot over the dead ball line. Under the rules of the time, if a player collected a still moving ball with a foot over the dead ball line it was a 20-metre restart. Initially, Warren thought Carige had done this.

But the ball had stopped when Carige touched it, meaning it was instead a drop out. It was an awful, inexcusable error at the worst possible time to get cute and technical with the rules. Carige, left to his own devices as Kent predicted, unravelled.

As referee Bill Harrigan explained the ruling, Carige looked baffled.

Seventeen seconds remained. 18-all. The drop out was a shank, Canterbury centred through Glen Hughes. They had one final chance but made another mistake of timing when Hetherington did not notice Hughes play the ball as quickly as he did.

As the Eels converged on Hetherington he did not have time to find Polla-Mounter or Halligan.

Silva saved the day, firing a quick pass to Relf, who let off a dog of a field goal attempt that never rose above shoulder height.

Carige collected the ball next to his own posts. As he waltzed over his own 10-metre line, the siren sounded. With just two players onside, Carige put a speculator of a kick in.

It was madness. Sterling groaned as the kick fell around the halfway line. Polla-Mounter replied with a prayer from 49 metres, to steal the game.

The ball hung in the air for an age. The crowd tried to roar it over. It looked good. The moment was silent and loud at once, as all eyes watched the Steeden.

“It’s fallen short!” said Warren, breaking the spell. Sterling agreed. But Canterbury went up as if they’d won it.

Polla-Mounter raised his arms, looking uncertain. Silva hoisted him high and was joined by his teammates. As Warren said, Canterbury were claiming victory.

Harrigan called for the video referee to check it, which was against the rules of the time. Not that anyone cared. Some things have to be right.

In this moment of chaos, drama and uncertainty, only one thing was clear.

“I can’t believe Paul Carige would have ever given an opportunity for that to happen,” said Sterling.

As a replay unfolded, all eyes were on the ball once more. As the ball travelled in the slowest of motion, even Sterling questioned what he had seen. “It’s over…..hang on, I don’t know if it’s over? It’s under, sorry!”

The former Eels legend summed up the feelings of every Parra fan on earth: “They led by 100 with 10 to go!”

And so to extra time. Ten minutes each way. The Bulldogs were old hands at this by now, what was once thought to be a weakness was now a strength. Five sudden-death appearances had shaved every edge off their game. They were battle-hardened, sure of themselves on every play. Parramatta were still trying to figure out what had happened.

PART FIVE: FATIGUE IS ONLY A STATE OF MIND

On the third tackle of overtime, Marteene made a long break and was pulled down 40 metres out. “Parramatta, they’ve really hit the wall,” said a concerned Warren.

On the last, the Bulldogs were 20 out on their left scrumline. Polla-Mounter potted a field goal from slightly off centre with absurd ease. Nobody from the Eels went near him. Forty seconds into extra time, the Bulldogs led 19-18.

Now it was Canterbury who looked composed and controlled, Canterbury who were rising to the moment as if they were born to it, Canterbury, with a collection of battlers, youngsters, old heads and one-offs, in control.

There was still 19 minutes to go, but Parramatta already looked dead. From the next set, Whereat knocked on the clearing kick. It felt like an hour since the Eels had last held the ball from more than five seconds.

The trend continued when Carige claimed Polla-Mounter’s next bomb. He caught it a metre away from the touchline and was duly dispatched into touch by Lester.

“He has made some of the dumbest plays I have ever seen in a game of rugby league, Paul Carige” said Sterling, the acid in his voice unmistakeable.

“Why he would have ever tried to catch that football, why he wouldn’t let it go for Lester to catch or let it bounce I will never, ever know. There was only ever going to be one result and that was him going over the sideline.”

Polla-Mounter was leading the game around the yard by now. He ducked into dummy half on the next set, threw a huge dummy and snuck over next to the posts. As Warren said, it could not have come to a player more deserving. There were 16 minutes left, but it felt like a knockout blow. It was 25-18, it may as well have been 100-18.

The final 14 minutes passed like a daze. The Eels went through their paces like robots. The Bulldogs stayed in control. In the 92nd minute, with hope still technically alive, Carige fielded a kick from Corey Hughes that was definitely going out on the full. There was no need to catch it, but he did. He then stepped on the sideline.

“That has capped today for the boy,” said Warren, as Carige screamed in frustration.

Polla-Mounter kicked another field goal in the 95th minute, because he could do whatever he damn well wanted at that point.

The Eels kicked a penalty soon thereafter to narrow the gap to six, but a sloppy pass from Jason Bell ended their final attacking raid.

Travis Norton pushed through some feeble defence and the match, which felt more like a life experience than a game of football was over, at last with the Bulldogs carrying a 32-20 lead, a grand final berth and footballing immortality.

“We said earlier Steve Folkes told his team fatigue was a state of mind. It’s nice to be able to say those kind of things, but for your players to react to it and believe it, it’s a different story,” said Sterling.

Jim Dymock embraced Polla-Mounter, the former teammates sharing a moment after the siren. The Canterbury players saluted the rapturous crowd and Parramatta shot through, perhaps still wondering how they had lost the unloseable game.

“We don’t have a camera in the box,” said Warren, as he tried to make sense of it all.

“But the most appropriate shot that we could take would be the face of Peter Sterling. I don’t know how he feels because I wasn’t anywhere in the vicinity of the joy of the Parramatta victories he enjoyed to become the most legendary of all Parramatta players.

“But he has got a very forlorn look on his face. Understandably so.”

It will forever be one of the greatest matches ever played. Critics can point to the high error count, the missed tackles and all that, but nobody ever created a masterpiece painting inside the lines.

PART SIX: CARIGE VANISHES, DESTINY CALLS

It was the fairytale to end them all, the kind of miracle that doesn’t happen in real life.

“Steve (Folkes) told us it was the gutsiest performance he’d been associated with since last week,” a jubilant Steve Price said afterwards.

“At halftime he basically said when we come off we don’t want any petrol left in the tank, we want to be able to say we tried out hardest and did our best to win.”

The beers were flowing after the game. How could they not be?

“They put us to bed, but they didn’t kiss us goodnight,” said Bulldogs president Barry Nelson to the Sydney Morning Herald.

Polla-Mounter revealed he needed a painkilling injection to play, which wore off around the end of regular time.

Halligan told Peter Frilingos of The Daily Telegraph he thought his equalising kick was going to miss.

“I held my breath but I reckon everybody else was doing the same.

“I rushed the earlier kick with 10 minutes to go, I thought I’d get in quickly and knock it over.

“The very next kick was from out wide, I took my time with it and I held my breath when it looked to be curling again before holding its line and going over. No matter how much practice you can you can only hope for a good strike.”

Carige spoke to The Daily Telegraph’s Tim Prentice. From the looks of things, he was still shell-shocked.

“I don’t know. I guess it was a bit of a brain explosion. Look, I was trying my best for the team, sometimes those little kicks come off and you come up with a win.

“I was hoping someone would be charging upfield and would get one of those great bounces.

“Sadly, it wasn’t to be. We gave it our best shot, I supposed it was an exciting game, good for the fans.”

The vitriol towards Carige was relentless and of fearsome intensity. He was forced to flee Sydney after “copping abuse wherever he went” according to Grantlee Kieza’s report in The Daily Telegraph the following week. This included vicious sprays on the internet, surely the first time a player copped it big time on the world wide web.

He was released the following month and never played in the NRL again.

One cannoth help but think his immediate departure exacerbated the infamy.

Carige is still a byword for a player putting in a performance of such spectacular ineptitude that it could end their career. Never, ever go full Paul Carige.

In the immediate aftermath, Brian Smith put it pretty simply — “Paul should have known better than that.”

There was some sympathy from Polla-Mounter.

“I couldn’t believe it when Carige kicked that ball. If my field goal went over it would have been the worst mistake of his life.”

Carige was not solely to blame for the loss — the Eels fell apart as a unit, Simon missed the simple field goal, their right side defence totally collapsed in the final minutes. — but the visibility of his mistakes, the foolishness of his choices, his disappearance, it turned him into a legend with a name as visible as any in the history of Parramatta and Canterbury.

There was still a grand final to be played and Canterbury seemed destined for glory, messiahs in blue and white.

With an irresistible run of form, the Bulldogs were powered by emotion, with several players shedding tears after the prelim.

“It sure was big, but especially big for Peter Moore, who everyone knows is doing it tough in hospital,” Steve Price told Tim Prentice of The Daily Telegraph.

“We celebrated as a team and did what we could to thank our fans. When I got to the dressing room, though, there were different kinds of emotion.

“I began thinking what a huge tonic the victory would have been for Peter and I’ll admit I shed plenty of tears.

“He was the guy who brought me to the club and he has been a very special friend to me.

“If we can go one further for the Bullfrog, I reckon we’ll have done more good for him than any medicine ever could.”

Arrangements were made for Moore to sit on the Bulldogs bench for the grand final.

“He’ll have a nurse from the rehabilitation unit and our doctor, Hugh Hazard — a lifelong friend, will also be on hand,” chief executive Bob Hagan said during the week.

“He’ll be on a wheelchair but it’s just great he’s going to be there.

“He will sit with the reserve players and provide a tonic for the team.”

Moore himself was under no illusions as to the size of the task at hand, but believed in his boys to the hilt.

“We are playing the best club side in the land,” he told Roy Masters in the Sydney Morning Herald.

“The odds are against us, but they have been against us the past two games as well.

“Canterbury is a club which thrives on adversity. Last week was the best example ever of overcoming the odds.”

Plans were made to chair Moore around the field if the Bulldogs won it all. It would have made for some of the most emotional scenes in the history of rugby league, the family club doing it one more time for the godfather. The Broncos were giving 10.5 points start, but who would dare bet against destiny?

AFTERMATH: ONE STEP TOO FAR

The Broncos didn’t give a shit about storybook endings. They crushed the Dogs in the grand final as the magic ran out and the weight of seven sudden death games finally caught up with Canterbury.

Brisbane first struck in just the third minute when Michael De Vere toed through a knock on from Talau to touch down. A Tony Grimaldi try followed from the Bulldogs before Kevin Campion pulled one back for Brisbane. Canterbury were given a shock half-time lead when Steve Price stepped through a gap and found Talau to score shortly before the break.

A 12-10 scoreline in their favour was positively cruising compared to the pits the Dogs had escaped in the past. Then the Broncos found a gear the Bulldogs simply could not match. They crossed barely two minutes after the resumption. The last true Canterbury chance came in the 49th minute when Talau kicked instead of passing to an unmarked Halligan with the tryline open.

From there it was a procession. Brisbane ran in four more tries for a 38-12 win, securing their fourth premiership. Just before Allan Langer and Tonie Carroll combined to put Darren Smith over for Brisbane’s final try, Warren put a eulogy on the season. “They’re waiting for the magic wand, but it’s not coming out today.”

No Canterbury fan or player should have ever felt ashamed of the loss. Brisbane were one of the great club sides of the modern era and the Bulldogs had already come so far, overcome so much. Parramatta would have dreamt of such a glorious run, even counting the way it ended.

The match could have easily broken Parramatta as a club the way it broke Carige.

But they rallied, rebounding to finish second in the regular season in 1999 before again falling in the prelim, this time to Melbourne. The next year they had a run of their own, going from seventh to the prelim before they ran into another Brisbane colossus. By 2001 they were the colossus, with a host of new names and a bold new outlook devouring allcomers except for the one that counted on grand final day.

The run of three lost prelims and a grand final defeat would be enough to send anyone round the twist.

But Smith lifted them up one more time. Another minor premiership followed in 2005, and again they were heavily favoured in the prelim until some plucky young Cowboys led by a skinny kid in headgear named Johnathan Thurston shut them out 29-0. Smith didn’t survive the following season, his legacy cruelly recalled as one of getting Parramatta to the line while being unable to take them over the top.

The scars remained — they lost another prelim in 2007 and a grand final in 2009. Prop Nathan Cayless had the grave misfortune to play in every single one of those losses. Nathan Hindmarsh was there for all but the 2005 prelim.

For Canterbury, 1998 was the end of one era and the burgeoning start of another. Moore passed away in 2000 after continuing to battle throat cancer. By 2002, when they won 17 matches straight before salary cap sanctions tore the life from them, only eight players from the grand final side were left.

By 2004, when they broke through for their most recent premiership amid a storm of off-field controversy, Grimaldi, the Hughes brothers and Price were the only veterans of the 1998 extra-time battles left. Folkes coached the club until 2008 and tragically passed away earlier this year.

Carige spent 1999 with Salford in England and played for Newtown Jets in 2000 before a nomadic career in local footy around Queensland.

He has never given a major interview about the game.