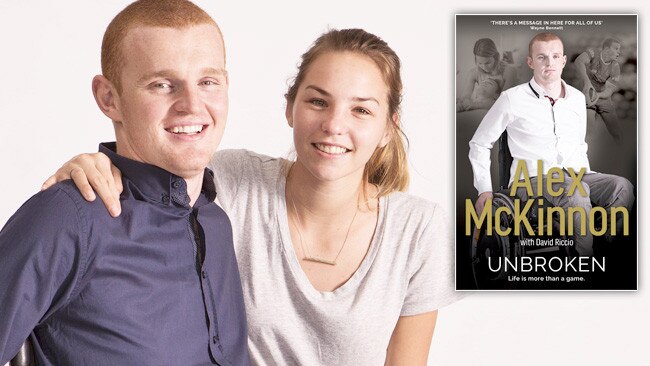

Alex McKinnon reveals the reality of rehab as he battled to recover from his tragic life-changing accident

EXCLUSIVE: Alex McKinnon reveals the reality of rehab at the Royal North Shore Spinal Unit. “What I experienced over the next three months I would not wish upon anyone, let alone someone 22 years of age.”

AFTER 14 days in the Intensive Care Unit of the Royal Alfred, I was transported by plane to my “home” for the next three months, the Royal North Shore Spinal Unit in Sydney.

What I experienced over the next three months I would not wish upon anyone, let alone someone 22 years of age.

The focus of moving to Royal North Shore was twofold.

One, I could be closer to friends and family and, two, it would allow me to edge towards a medically stable condition while also slowly increasing my rehabilitation.

The original plan was to be at Royal North Shore for four weeks — after which my condition was thought likely to stabilise — before then shifting across the city to a specialised spinal injury care and rehabilitation clinic, the Royal Rehab at Ryde.

However, due to an unfortunate and alarming spike in spinal injuries across NSW over the March-April 2014 period, I had no conceivable alternative but to remain at the Royal North Shore Spinal Unit for what would end up totalling 12 weeks.

I was not prepared or equipped for the mental anguish I would encounter during this period. I had left Melbourne in a positive frame of mind.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY: McKinnon’s pain over reaction to his accident

MISTAKE: How did 60 minutes get it so wrong?

BUZZ: The night I was ashamed to be a league fan

KENT: Smith showed greatness when it mattered

BOUNCE BACK: Tapine ready to repay Knights

The doctors had told me that my greatest potential for improvement in my recovery would be in the first six months after the accident.

So I was focused on doing everything possible to regain what I had lost. In my favour was the fact that my injury was presenting well, I could talk and I had had full feeling return to my arms and legs.

I was now intent on answering the questions which my doctors had so far been unable to give me, like will I walk again? I spent the first four weeks learning how to use an electronic wheelchair. The L-plates that were attached to the back of my seat were more than just a cheap laugh.

Learning how to operate a contraption without being able to move my hands or arms was extremely testing.

To illustrate how useless my arms were at the time, the only reason I could steer the wheelchair was because there was an armrest. If there hadn’t been an armrest, my arm would have dropped to my side.

I ran over Teigan’s foot on one occasion, while quite often the only way I could stop the two-wheeled machine was by ramming it into my bed. And the challenges weren’t only physical.

I NEVER considered how hard it would be at RNS to hang onto the positive approach I that I had arrived there with, as I took up residency alongside other patients with varying degrees of spinal injury.

Perhaps because my fellow patients were aware of who I was, due to the publicity my injury had garnered, they often turned to me to share their own fears and the anxieties that they were feeling.

We fed off each other’s stories: a community of people with spinal damage. I felt comfortable playing that role. I felt like I was a leader.

But I wasn’t prepared for the impact that that role would have on my own recovery.

Each day I would be thrust into a vortex of complex emotions that would rise and fall as new patients with spinal injuries would join the ward.

Just when I felt like I was moving forward, making my own progress, a patient with a fresh spinal injury would enter the ward, fighting the very same demons that I — and many others — had just confronted a few weeks before.

I would see families slumped in their son or daughters room, overcome with anguish — just like the families that had come and gone before.

I wanted to help in any way I could. So I would speak to them about their injuries and my own experience in the hope that my situation, while equally as uncertain, could somehow provide them comfort.

But it was taxing on me emotionally as I, too, was still trying to process how I would move forward with my own life.

It was like having someone point a remote control at me, pressing “play, stop, rewind”, “play, stop, rewind” again and again and again for three straight months.

Unable to move my arms or legs to increase my body temperature, I would be shaking by the time I was hoisted back to bed. This was my new reality.

THE routine of rehabilitation created a level of exhaustion that I have never experienced before. Over the course of those three months, my blood was taken every second day at 6.30am. At 7am, I would be given my jar of medication.

I would take two Panadols, two magnesium pills, one Panadeine Forte, one Baclofen and one multivitamin. I would then repeat the same dose before bed each night.

One of my goals at the time was to wean myself off the medication as quickly as I could. It would ultimately take me four months, to the point where I now just take two Panadols and two magnesium pills.

Each morning, I would be fed at 8am.

A volunteer carer, almost always someone that I had never met in my life, would arrive in at the door to feed me.

I felt like a baby as they spooned me breakfast wearing rubber gloves. It was humiliating and demoralising.

It was not the person’s fault. But I could not go through that process, I didn’t feel human. So I stopped eating breakfast.

I would be hungry, but Ijust wouldn’t eat. After the breakfast shift was over, I would then be hoisted from my bed to a chair — a chair which sat over the toilet.

One carer was allocated the job of caring for three patients, so I would have to sit on the toilet for an hour before my carer had finished with the other two patients on their round.

I had a button to press when I had finished on the toilet. I would be finished in five minutes.

At that time, my blood pressure remained dangerously low, simply because I was always sitting in my wheelchair or laying in my bed.

Some mornings I would be put on the toilet and my carer would leave, which meant that I couldn’t move to regulate my blood pressure. I passed out on more than one occasion.

From the toilet, I would then be moved to a shower chair, where I would be showered by my volunteer for 20 minutes.

I would then need two people to put me back into bed. I would have to sit naked waiting on the shower chair, until a second person arrived.

Unable to move my arms or legs to generate an increase in my core body temperature, I would be shaking by the time I had been hoisted back to my bed. This was my new reality.

In life you can be as stubborn as you want to be, but sometimes you’ve got to be smart enough to say “Hey, I actually do need some help.”

NEITHER Mum or Teigan were allowed inside my ward until 11am.

As uncomfortable and degrading as each morning was, I was determined from very early on that neither Teigan nor Mum would be my carer.

For them to look after me, it would mean that I would be dependent on them for the rest of my life, and that was something that I didn’t want.

I was focused on finding the right balance in my relationship with Teigan and any hopes of a lasting life together just wouldn’t have been plausible if she was forced to feed me and clean me. However, I sometimes I just couldn’t help it.

I suppose in life you can be as stubborn as you want to be, but sometimes you need help and you’ve got to be smart enough to say “Hey, I actually do need some help.”

It was such a difficult situation to comprehend because, just a few months earlier, I had been the one who happily cooked and cleaned for the both of us.

Physiotherapy sessions began at 11.30am each morning and would run for an hour.

There was an extra optional session that ran from 1.30pm until 2.30pm. I was the only person who turned up to both sessions every day. I found those sessions mentally draining, more so than physically.

Picture me, a footballer who would attend at least two weight sessions a week in the gym, now sitting at a table with a silk cloth resting under my arm, my focus for an entire hour being to slide my arm back and forth like a windscreen wiper in an attempt to regain strength in my pecs.

EVERY spinal injury is different. Every patient is at a different stage of recovery. Change can happen overnight. Some patients might begin to stand after not being able to budge an inch 24 hours earlier.

I was attending every session yet I just couldn’t see much improvement. It was shattering.

Especially as I’m a person who has always held the view that the harder you work, the better you’ll get. It’s what made me the footballer I was.

Every day, I woke up committed to doing everything that I could. But I just wasn’t improving like I had wished and like some of the other patients were.

The doctors had told me these early months were the most important in my recovery, so I would lay in bed at night, counting the days, and creating a list of all the things that I had achieved.

I do not want to sound like I’m the only person in the world to have sustained this injury.

There are thousands of people much worse off than me. There were patients at Royal North Shore much worse off than me. But all I can explain is how I felt.

And when you want to improve, and you’re doing everything possible to improve, and you’re being left behind by the people beside you, it is an agonising and tormenting way of life.

I have great empathy for others who are in this situation.

BY the end of the second physiotherapy session each day, I was spent. And I mean completely and utterly exhausted.

I wanted to get to my bed and let my muscles relax. However, there were certain times allocated for when patients could be lifted back into your bed.

The lift rounds were 1.30pm, 4.30pm, 7.30pm and 10.30pm. You could only go back to bed at those times.

If you missed the 1.30pm timeslot, you couldn’t go back to bed until 4.30pm — and so on and so forth.

The hardest part for me was the fact that, ever since the accident, the most comfortable place for me is in bed. It’s the one place where my entire body is relaxed.

I’m not struggling to sit up, I’m not struggling to stay calm, my arms aren’t hanging, my shoulders aren’t aching — I’m just comfortable.

But for me, wanting to be in bed is a brand-new state of mind that I can’t get my head around. I was the most active person: I never wanted to sit on the lounge or laze around.

I was the kid not wanting to leave McKinnon Oval until after dark. I always wanted to mow the lawns or wash the dishes, put the bins out — whatever.

Now I’m my happiest when I’m in bed? It just wasn’t me.

While the improvement was slow, the important thing was this: there was improvement.

In the space of six weeks, I increased the strength and movement in my arms and I gained more control in my stomach. I had also moved out of the electronic wheelchair and into the same powered-assist wheelchair I remain in today, which is smaller and a lot easier to control.

Just over five weeks earlier, I had been preparing to play alongside them and now I’m sitting there in a wheelchair.

THAT visible improvement was hugely satisfying and perhaps proof that it didn’t matter how deflated I felt; I was improving.

And I thought back to when my old mate from St George- Illawarra, Trent Merrin, paid me a visit at Easter.

He knocked on the door of my room at the RNS wearing an Easter bunny outfit.

I had no idea who was inside the suit. A voice said “Hold out your hand if would like an Easter egg, young man.”

At the time, I couldn’t hold out my hand. I couldn’t feed myself and I couldn’t hold a drink. But after eight weeks, I was now feeding myself again.

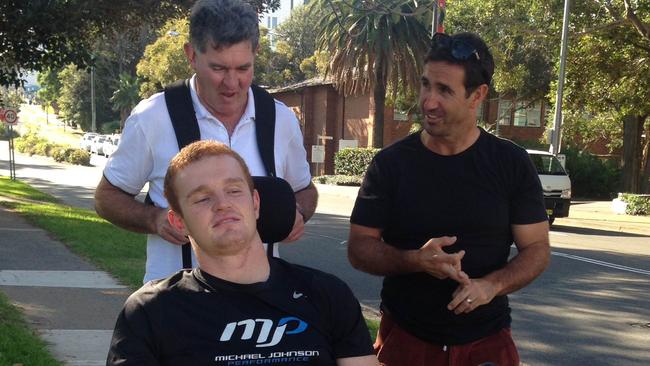

Visits like the one from “Mez,” my Newcastle Knights teammates and my old mate from schoolboys footy, Boyd Cordner, gave me a timely distraction and a reason to improve, so that the next time they stopped by, I could show them my development.

For the same reason, I made a rare venture outside the RNS — attending my first Newcastle Knights match just five weeks after the accident.

The Knights were playing Canterbury in Round 8 at ANZ Stadium at Sydney Olympic Park. I honestly have no idea how I went to that game.

I was still in a bad way mentally and physically. I was on heavy painkilling medication, but I just wanted to be around the boys. The Canterbury club and ANZ Stadium were fantastic in accommodating Teigan and me that night. I could not have imagined what it felt like for the Knights players to see me sitting there in a wheelchair before kick-off.

Just over five weeks earlier, I had been preparing to play alongside them and now I’m sitting there in a wheelchair.

A lot of people suggested to me that attending that match would only crush my spirits further. But it was quite the contrary, I could not have been on a greater high, just to be back among the boys again — although the medication may have altered my senses slightly!

IT was only a few weeks later that I received a phone call from my Newcastle Knights teammate, Danny Buderus, about a teenager from Coffs Harbour who had fractured his C2 and C3 vertebrae in a tackle while playing for his local rugby league team.

Curtis Landers had been transported to the RNS spinal unit. I told “Bedsy” to get a message to Curtis and his family to visit me in my room where we could meet and chat. It was five days later that I met Curtis and it was striking how similar his condition was to mine.

He was presenting the same mobility as me, his limited hand function was the same, and yet I’m looking across at him in his wheelchair feeling terrible for the fact that he is just 15 years old.

I know I’m only a few years older, but in the bigger picture, he had not yet had half of my life experiences.

He hadn’t even driven a car. As I was chatting to Curtis, he coughed. And it was a normal cough. I thought “That’s odd.” He was presenting exactly like me, his movement was similar to mind, but I can’t cough because my intercostal muscles don’t work.

So I told him: “Mate, that’s a pretty good sign. I know it may not seem like much, but that’s massive.”

“Is it?” Curtis said.

And right from that moment, I was confident he was going to enjoy a promising recovery.

After our initial conversation, I didn’t hear from Curtis for a few weeks, until one day he texted me saying he had been moved to the Children’s Hospital at Westmead. He asked how I was going and said that he had his catheter taken out today.

“Have you had yours taken out yet?” the text message from Curtis read. I could only reply “no”.

It was confirmation to me once again that his improvement and rehabilitation was going to be significant. And ever since it has been: he’s made a full recovery that is wonderful to see. You would never wish this predicament on anyone so I’m very happy for Curtis.

It has been an eye-opening experience for me to see the transformation of Curtis because it’s the recovery the doctors were hoping I would achieve. I had so many positive signs in the beginning.

But my improvement just didn’t kick-on like Curtis’s did.

To buy the book, visit alexbook.com.au