Sydney to Hobart 1998: The Sword of Orion rescue mission

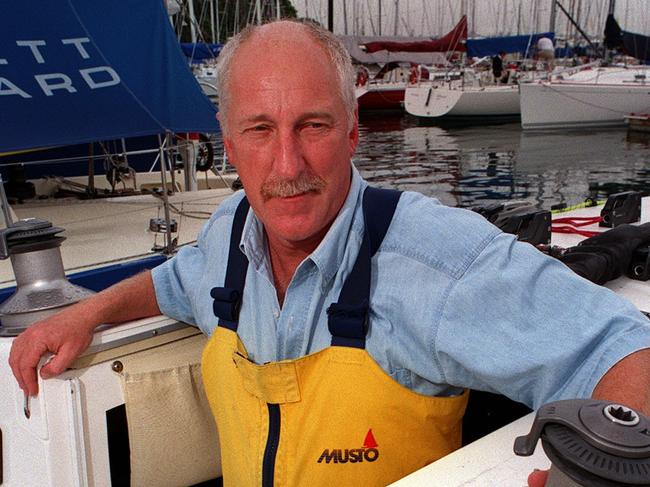

Captain Marc Pavillard has been to war twice and is now a chief of staff at the Department of Defence. In 1998, he found himself hovering in a helicopter above a stricken yacht in the Sydney to Hobart. Amanda Lulham reports

- Bass Strait Bomb taught skipper life lessons

- How a 12-year-old survived 1998 carnage

- Sounds of panic and hysteria haunt skipper

“Our Radar Altimeter was working overtime in the hover and telling us the truth: the waves were regularly at 80ft and sometimes reached 100ft.”

Captain Marc Pavillard RAN has been to war in the Middle East twice, been shot at and is now Chief of Staff at the Information Warfare Division at the Department of Defence. Two decades ago, after having a relaxing afternoon with family interrupted by a phone call, he found himself hovering in a helicopter above a stricken yacht in the Sydney to Hobart.

Marc Pavillard was part of the biggest maritime search-and-rescue mission in Australian peacetime.

The courage and skill of rescuers helped prevent a higher death toll than the six men lost in the deadliest storm in race history.

And while he remembers in minute detail almost every horrifying aspect of the hazardous helicopter rescue to save the lives of the Sword of Orion crew, one moment at the very end stands out.

MORE:

INSIDE THE DARK DEPTHS OF TERROR

“I’ll never ever forget the faces of the Sword crew as we abruptly broke clear of the storm on the way home,’’ he says.

“It was as if this thick curtain had just been opened into the most magnificent blue sky day you have ever seen.

“I was shocked by it. They couldn’t believe what they were seeing. I got it because they had been in hell for a couple of days and just on the other side, within their reach, was this realisation of paradise.’’

In the 1998 Sydney to Hobart race, six men lost their lives, 30 civil and military aircraft helped rescue 55 sailors from 12 stricken yachts, five boats sank and seven were abandoned.

Just 44 of the 115 starters made it to Hobart.

“Still, to this day, 32 years in the Navy, its still the most important thing I have ever been involved in,’’ Pavillard says of the rescue.

One of the men lost at sea was British sailor Glyn Charles, who had been steering Sword of Orion when it was smashed over and under by a rogue wave of horrific proportions.

With wind reportedly gusting past 90 knots and waves recorded looming over 80 foot masts, crews were in survival mode and Sword of Orion was attempting to head for safety when disaster struck on December 27, the second day of the race.

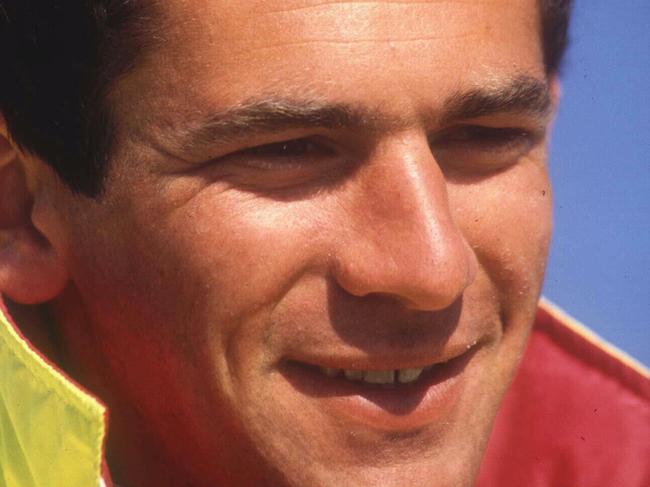

“The wind was amazing — it hurt, says Sword of Orion crewman Adam Brown. “It was actually kind of deafening. The waves were roaring as they rolled towards us.

“It was like the sound of an aircraft taking off. You were very sensitive to the noise because you knew what was coming,’’ .

A monstrous wave knocked the boat over, rolled it 360 degrees, before righting itself.

In the melee Charles went overboard. His body was never recovered.

“There was no base to the wave. I could see the sky through it,” Brown says.

“The boat fell sideways, then rolled, free-fell off a wave as big as a five storey building.

“We were caught up and the boat rolled like a barrel, 360 degrees.

“I tore the whole companionway out of the boat, injured my shoulder and landed on Rob (Kothe, skipper) and broke his leg in 15 places

“We were caught up and the boat rolled like a barrel, 360 degrees.

“We became dismasted, the engine broke off its mounts, and we fractured the hull.

“Glyn was washed overboard. All reports are the boom washed across the deck and snapped both his tethers.”

The crew radioed for help and then set about bailing as much water from the boat as possible as they waited for rescue.

“We used sea boots, saucepans, anything we could get our hands on,’’ Brown said.

Hours later, around 1am, a Navy Sea King rescued Darren Senogles, Nigel Russell and Steve Kulmar off the stricken Sword of Orion.

Pavillard and his Seahawk team were involved in the rescue of the remaining six.

It wasn’t what he had expected to be doing over the Christmas break.

“I got a call from my Flight Commander, a call that changed everything. ‘Pav, he said, you’d better not drink that beer mate, we need to get our arses down to Nowra and airborne ASAP’. Things are going to shit in the Sydney to Hobart race and they need our help.”

By 2.30am Pavillard says he, aircraft captain Adrian Lister, co-pilot Mick Curtis and winch operator Dave Oxley “launched into the unknown.”

“We had taken off into clear skies but within minutes we had been swallowed by the ferocious storm,” he says.

”Zero visibility, huge winds, driving rain and cloud bases nearly down to the water. And the turbulence … at times it was like we were in a shopping cart bouncing down a flight of stairs.’’

Pavillard and crew finally sighted Sword of Orion about 4.15am, contacted the boat via radio to work out a plan which saw them delay the rescue until the crack of daylight.

They knew they had only around 30 minutes to effect the rescue of all six men before their fuel level would drop too low to get them safely back to land.

This meant not sending one of their own down to assist in the winch rescue.

At 5.15am the rescue began with Andrew Parkes and Sam Hunt.

“It was then that we really began to understand the conditions the yachts were experiencing. The swell and waves were enormous,’’ Pavillard says.

“But seriously, our Radar Altimeter was working overtime in the hover and telling us the truth, the waves were regularly at 80ft and sometimes reached 100 foot.’’

Next was Brown, hit by a wave when on a strop and washed forward, his wire caught in the right main landing gear and rubbing dangerously against the steel axle hub.

“Had it snapped it might have recoiled into the main rotor blades and taken us down,” Pavillard says.

Brown was lifted to safety but Pavillard then discovered damaged wires in the winch.

“In hindsight, this was a huge call, a real turning point. If the wire had failed during subsequent rescues, we could have had deaths on our hands,’’ he says.

“On the other hand, we had no idea how much longer the yacht would stay afloat and no idea when another aircraft might get to them. Again, potentially deaths on our hands.

“No easy answer, but I think in emergency situations there rarely is and you’ve got to make the best call you can.”

Skipper Rob Kothe, with his leg in a splint, was rescued next, then Simon Reffold and finally Carl Watson, struggling to get the strop on before being winched 150 feet to safety.

“That was the most intense 30 seconds or so ever … all I could think of was him falling from height into that violent ocean, knowing that even if he survived the fall that we wouldn’t have time to try again,’’ Pavillard says.

Back on land, a maintenance official later gave the winch cable, with six broken strands, a tug with his hands and it snapped.

“How different it all could have been,’’ Pavillard says.

Recently Pavillard accepted an invitation to talk at a dinner for the SOLAS Trust which was set up in the wake of the deadly Hobart to assist the immediate needs of the family of those lost at sea, provide assistance to search and rescue organisations and to foster research and training to improve procedures and equipment for use at sea.

There, for the first time in 20 years, he met some of the men he has rescued.

“It was incredible. Just so great to see then,’’ he says.

Brown, his rescue number three, on Boxing Day is heading back to sea in his 29th Sydney to Hobart on the 52-footer Gweilo.

He was one of the sailors who returned to the race a year after the 1998 disaster and has competed in almost every one since.

But when he heard Pavillard talk about the rescue of he and his crew 20 years ago he was genuinely shocked.

“I had never heard the helicopter perception on any of the rescue operations. If I thought it was bad on the boat it was almost worse for the he helicopter,’’ says Brown, now a multiple overall winner in the Sydney to Hobart.

“I had never heard that about the winch either. It just shows us how so many more lives could have been lost that day. Even more credit to these guys who risked their lives.’’

Every Test, ODI, T20I, and BBL match live & ad-break free during play. SIGN UP NOW!