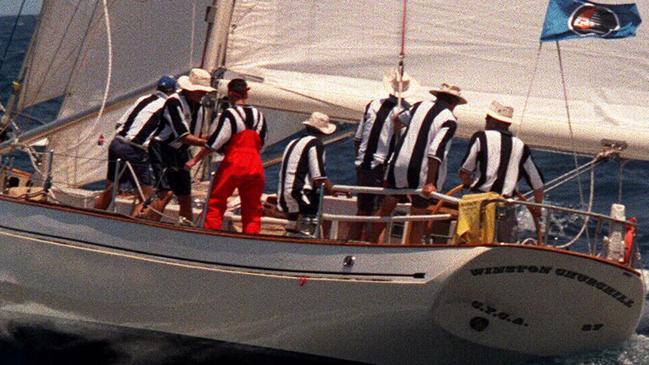

Inside the 1998 Sydney to Hobart disaster and race for survival

It started as a race to Hobart and became a fight for survival. Two decades on, tales told at the end of the race are still vivid. Sailing writer AMANDA LULHAM remembers.

- Bass Strait Bomb taught skipper life lessons

- How 12-year-old survived 1998 carnage

- Skipper remembers: ‘I can still see the boat sinking’

- Sydney to Hobart: Recalling the killer storm of 1998

IF there was one place you didn’t want to be when the beaten yachts with their battered crews straggled in at the end of the 1998 Sydney to Hobart, it was down below deck.

From the wharves of Constitution Dock in Hobart, where the yachts were moored after raging against a 36-hour storm that ripped the fleet apart, you could smell the sourness, sweat and vomit coming off the boats.

Despite the putrid smells around him, one skipper was going nowhere. He had hidden himself away down below and would not come up on deck.

“Go say hello, see if you can get him to come up,” a crewman told me.

Below was a mess. Everything had turned turtle – upside down – from the storm.

At a wooden navigator’s table sat the sailor. Ashen-faced but seemingly quietly composed, there was not an ounce of movement from him.

Walking towards him, you could see his hands were gripped tightly around the table and had turned a pained white. This skipper – a man who had lived all his salty life on the sea – was locked in utter fear.

As I gently stroked his hands, he eventually released his grip and this race veteran was coaxed away from the tiny haven he had found during the race.

He never returned to do another Sydney to Hobart.

Neither did the young sailor who stood straight and tall at the Hobart pub later that same day, staring ahead blankly. Another in obvious shock.

Patrons gave him a wide berth – out of respect for what he had just been through and because he had neither showered nor changed since coming ashore.

He talked of death: how he could not stop thinking the giant yacht that had been his home was now a giant coffin.

How he had been below when the boat launched off a wave, became airborne then landed with a horrendous bang at the bottom of a wave.

How he and crewmates thought they were going to die and had cried.

He sobbed again as he confessed his shock at how scared he had been on board.

These sailors are a breed apart.

Earlier in the day, one of the biggest, toughest and strongest men in the race got off his yacht and hugged me so hard it hurt.

His skipper looked at me and shook his head.

“Don’t let him fall apart, he has to stay strong,” said this ocean-racing veteran.

When the shocked sailor started to shudder, the skipper and some of his crew grabbed him by the collar of his wet-weather gear unceremoniously.

“That’s enough, mate, Come on, let’s go have a drink.”

And they did. Not in celebration but in solidarity for what they had been through.

The trauma was real. These men and women had survived a war with themselves and the sea – one they weren’t trained for, one that ambushed them.

In most instances these were ordinary people – accountants, builders, teachers, students, policemen and marine industry workers – put into extraordinary positions.

They had started a sporting event on the most stunning of days on Sydney Harbour – as 53 fleets had done before them – and they ended up in a race for survival.

At one stage, early on December 27, I had grabbed a piece of A4-sized paper from a fax machine in the press centre based at a hotel in Hobart and started jotting down a list of boats and sailors unaccounted for – boats that hadn’t called in at the compulsory positional report, boats in distress, boats abandoned and, as we would later discover, boats that had sunk.

At one stage, at the height of the storm, this list had more than 50 names on it.

Through the heroic efforts of search-and-rescue personnel and other sailors, these names were slowly scratched off – including two of my friends winched off their boats – until six remained.

To this day, I can say their names without pausing: Mike Bannister, John Dean, Jim Lawler, Glyn Charles, Bruce Guy and Phil Skeggs. Rest in the seas.

Every Test, ODI, T20I, and BBL match live & ad-break free during play. SIGN UP NOW!