Two decades after the Olympics, promises of transformation might at last be realised

After winning a gold medal for delivering the 2000 Olympics, Sydney was in the box seat to turbocharge its transformation into a city for the 21st century. But it lost its mojo and was plunged into a “lost decade” — the effects of which are still being felt today.

After winning a gold medal for delivering the 2000 Olympics, Sydney was in the box seat to turbocharge its transformation into a city for the 21st century. But instead of capitalising on the momentum of the “best ever” Games, governments, businesses and bureaucrats rested on their laurels, Sydney lost its mojo and the city was plunged into a “lost decade” — the effects of which are still being felt today.

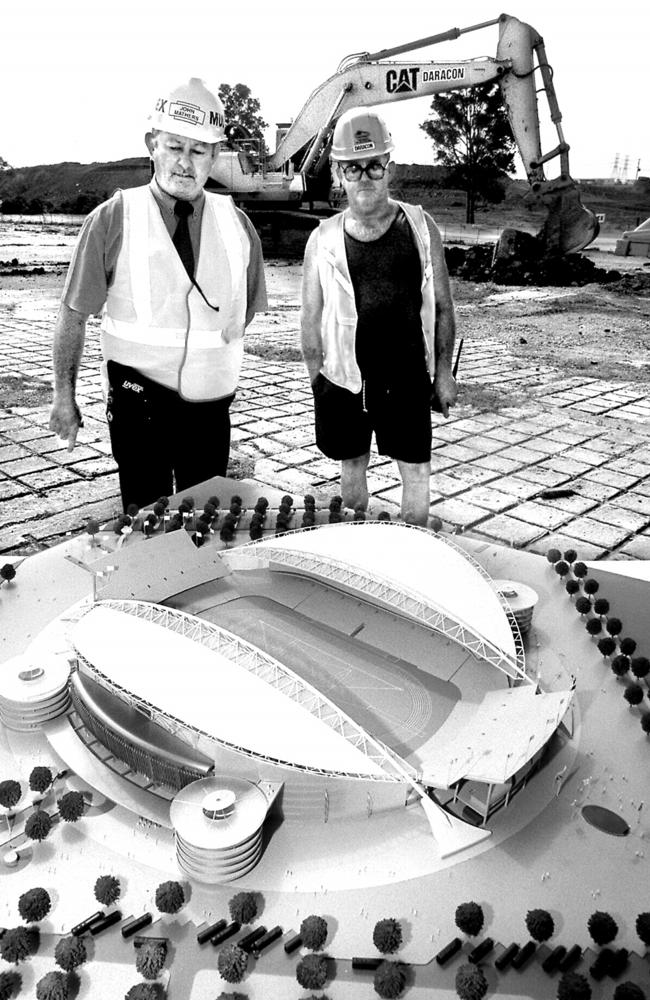

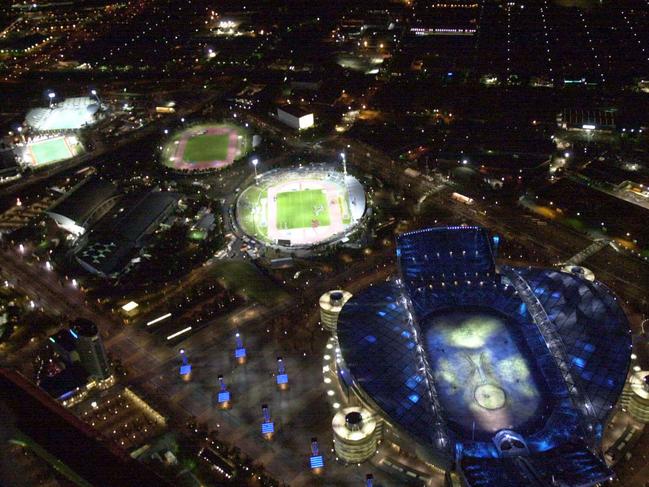

Delays to key city-building infrastructure, including vital road and rail projects, are only now being addressed with plans to turn Sydney Olympic Park (SOP) into the destination suburb that was envisaged after the Games.

MORE NEWS:

Supervisor charged over strawberry sabotage

Karl’s in-laws host special pre-wedding high-tea

New codes for loud parents at kids sport matches

The Metro and light rail will finally provide the transport connections that the existing rail spur line, built for the Olympics, fell short of delivering. And planning experts say SOP is starting to develop its own “vibe” and will be transformed in a similar way to the central city when residential apartments make it a living city at night time.

It’s not a moment too soon, according to former head of the Department of Premier and Cabinet and Transport for NSW John Lee.

“Homebush is becoming (a living city) now — good towers, dense living next to transport that is giving it character. It has taken a long time to develop,” he said.

Mr Lee said the Olympics were on time and on budget but did not deliver a legacy.

“There have been lots of good assets built but the lost opportunity was around transport infrastructure and tourism at that time,” he said.

“Now a Western Metro is planned between Parramatta and the city with a stop at SOP — it will be 12 minutes on that train from the CBD direct into the Olympic Stadium. That should have been done 18 years ago but now probably will be when you and I are in a nursing home. It will be the big differential but unfortunately it will have taken 30 years later than the Olympics.”

And Mr Lee contrasted Sydney with London’s Olympic legacy.

“One of the big soccer teams in London — West Ham — plays out of the Olympic Stadium because they grew it for the Games and shrunk it post-Games. Those smarts and that technology wasn’t there 15 years beforehand,” he said.

“In Sydney they built a little yoyo railway for the Olympics — if they had joined up with the main Western line it would have been transformational for that area. That was their big mistake.

“But there have been a lot of positive legacies. There is a lot of good athletics infrastructure and probably a million kids who learnt to swim at Ryde pool, where the water polo was played, and probably another two million kids at the Aquatic Centre at Sydney Olympic Park.”

Tourism lobby group chief Chris Brown has described the 10 years after 2000 as a lost decade. “We squandered an opportunity that was given to us by a lot of hard work and taxpayers’ money to get the bid by not following through with the momentum,” Mr Brown said on the 10-year anniversary of the Sydney Games. “We didn’t take advantage of the Olympic opportunity.”

For a handful of magical years Sydney had a can-do spirit that was the envy of the world and, according to hard-nosed former Olympics minister Michael Knight, the intangible legacy of Sydney 2000 was pride. Planned meticulously, the Games were embraced by Sydneysiders and ended with a AAA rating that gave the city global credibility.

“Staging the Olympics so successfully legitimised a wider feeling of pride (in Australians),” Mr Knight said in a rare interview for the Bradfield Oration. “The world looked at Australia and we liked what they saw.”

Mr Knight believes the spirit has endured since the heady days of 2000 but he agrees NSW moved too slowly to build on the mass transport arrangements pioneered during the Games.

“Both sides of politics were slow to get enduring transport to Sydney Olympic Park (SOP) … a Western Metro with a stop at SOP,” he said.

“One thing we did was to untangle the railway lines so they were not crossing each other — State Rail has carried on with that and done a fair bit but you can still see when there is disruption on one line how fast it spreads to the network. They have gone some of the way with (improving) that but they are not there completely.”

Arguably the greatest legacy of Sydney 2000 is the radical change in the way business is done in NSW.

Olympic-style fixed-price contracts and enterprise agreements for major projects have replaced the hated cost-plus regime that came with price blowouts, strikes and industrial blackmail.

“This has completely changed the way construction contracts are awarded and is now the norm for the way building is done in NSW,” Mr Knight said. “There are rewards for reaching each milestone and profits for finishing early are shared by the workers and owners — the beauty for the taxpayer is no cost blowouts. Then there are the environmental things … at the time Newington (the Games Village) was the largest solar-powered suburb.

“All of this stuff was groundbreaking and it has flowed through to today.”

Hosting the Olympics provided the infrastructure to stage the Rugby World Cup in 2003 and other major events but it was years before a new convention centre — crucial to attract international conferences — was finally built at Darling Harbour.

Predictions of a post-Games golden era soon proved wide of the mark. Tourism numbers fell and analysis by Monash University found the Olympics produced a net consumption loss of $2.1 billion. But now the master plan for 2030 provides for a population of 23,500, 34,000 jobs, education sites, parklands, retail space and a $24 million pool in the “biggest ever revitalisation of SOP”.

An official who worked closely on the preparations for 2000 is adamant the Games have “stood the test of time and wiped out the naysayers”.

“No one has a bad word to say about the Sydney Olympics which have been a complete vindication,” they said.

Lack of public transport sends residents off the rails

Families living in the former Olympic Village say they have been left behind by a lack of access to public transport.

Nadia Amato was raising two young children when she drove through Newington in 2005 and was struck by the big houses built on land formerly occupied by Olympic tents.

Her family spent $550,000 on a two-storey home — which is now worth more than $1.3 million — and raised her two children in the “family friendly” suburb.

However, as the years wore on, Ms Amato realised some vital infrastructure had been overlooked.

“I think public transport could have been thought out a little more,” she said.

“I can’t help but wonder when they put in Olympic Park train station … if they had considered a suburb was being developed under their noses, surely they would have realised (the need) for another station.

“There’s train stations in different directions within a 2km radius from our house — that’s OK for us but might not be for others.

“There’s no bus directly to the city and I think they missed the mark on that. To get to the city you need to get a bus and then a train.”

Ms Amato also said Sydney’s growing population was putting pressure on suburbs such as Newington.

“There’s just a lot more people here,” she said. “It was like a ghost town at the start, it just wasn’t a busy place. Now I struggle to get a park in my own street.”

Vision of peerless pioneer

Vision and patience are two adjectives often used to describe Sydney’s great designer, John Job Crew Bradfield.

The engineer responsible for the Sydney Harbour Bridge and the City Circle rail line persevered with his idea to build our famous “coathanger” as he foresaw linking north and south of the harbour would be a step towards creating a city of international significance.

Bradfield travelled the world researching before settling on the arch design based on Hell Gate Bridge in New York City, a single arch structure crossing the East River between Queens and Manhattan.

“The city proper will become a New York in miniature while North Sydney, Mosman and Willoughby will merge into a second Brooklyn,” he said.

Bradfield was also an inspirational communicator able to bring politicians and everyday people along with him.

“Sydney as we know it today couldn’t survive without such a grand scheme, almost all of which came to fruition,” emeritus professor Peter Spearritt, author of The Sydney Harbour Bridge: A Life, said.