Bradfield Oration 2017: Sir David Higgins’ speech in full

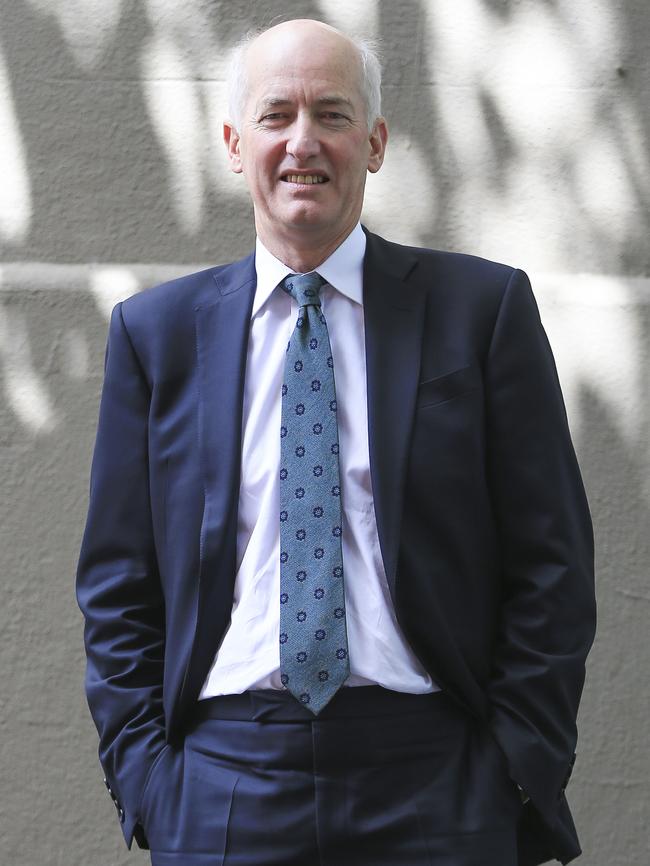

SIR David Higgins, one of the Australia’s most influential and visionary businessmen, delivered the Bradfield Oration tonight, speaking about what is needed to equip Sydney for the future, including transport, housing affordability and quality of life.

Project Sydney

Don't miss out on the headlines from Project Sydney. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SIR David Higgins is one of this nation’s most influential and visionary businessmen.

The 63-year-old, who has a degree in civil engineering, has many career highlights, including being boss of Lendlease when it oversaw the transformation of Homebush Bay into the world-class Sydney Olympic site for the 2000 Games.

He has worked in London for the past 18 years and is now chairman of Gatwick Airport, as well as chairman of Europe’s biggest infrastructure project, the £65 billion High Speed 2 rail.

This is his Bradfield Oration speech in full:

Thank you for that kind introduction - and thank you for the honour of being asked to deliver the Bradfield Oration.

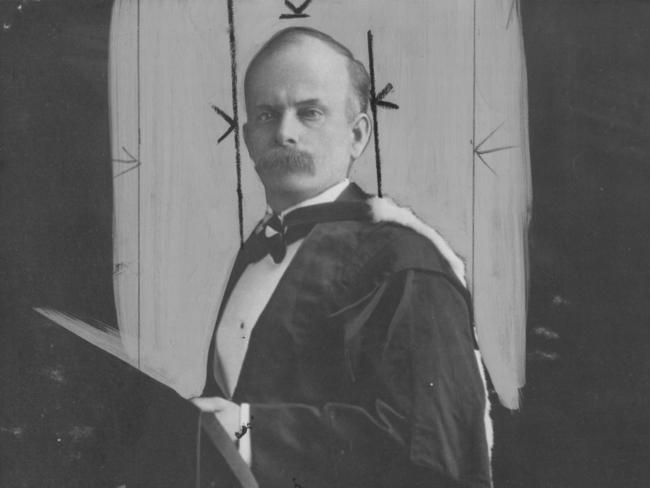

John Bradfield was, first and foremost, an engineer and, as an engineer myself, it is a real privilege to be asked to speak in his memory here in Sydney — and to speak about the future of this city that has been both a home and an inspiration to me throughout my career. I may have wandered, but I still return. And I do so for a reason. I want us, and our future “us” to succeed - and that is the key to what I want to say today.

‘BUILD A BRIDGE SYDNEY, AND GET BUILDING THE FUTURE’

Because, of course, John Bradfield wasn’t just an engineer. He was also a visionary: someone who saw what was necessary to make this city located on the world’s best natural harbour actually work in the early decades of the last century.

He was a strategist, a big picture person who saw beyond the ins and outs of the day to day, the ups and downs of immediate events to the fundamentals that were necessary to make Sydney work as a conurbation at the start of the 20th century.

He joined up the dots between what nature had given us with what was necessary to maximise its economic potential.

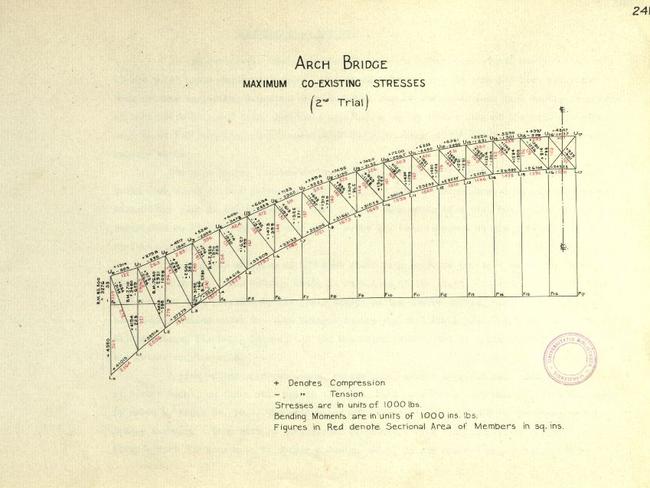

In 1912 he submitted the first proposals for a bridge to cross the harbour and then, three years later, his proposal for an electric underground. It took a decade before the first stations opened on the latter, and a further two decades before the bridge was completed.

So Bradfield wasn’t just a big picture person. He not only had the vision to see what was necessary to make Sydney work. He also had the patience, drive, skill and persistence to make that vision a reality.

And today we are still living off his vision. Today millions of us each year travel across the bridge and use the underground without ever thinking of John Bradfield. We pay him the ultimate compliment for an engineer. We take his work, his vision for granted - precisely because it works. He saw what was needed to make the future of Sydney work, and he delivered. That is his legacy.

But, whilst we know what John Bradfield’s legacy was, the question I would pose is this: what do we think this generation’s legacy will be, or should be?

Do we have a long term vision for the future? Can we rise above the immediate to see what is necessary to equip Sydney for the future - and the clarity, drive and patience to see that vision through to delivery?

A lot happened in Australia and the rest of the world between 1912 and the early 1930s, but still John Bradfield turned the concept of a cross harbour bridge into reality. Do we have that focus, that perseverance?

What does this generation want to be remembered for? What is the game-changing vision this generation will produce that people will still be talking about in Sydney in 2117?

I ask the question partly because, having lived and worked in London for the past 18 years, I am reminded on a daily basis of just how much one generation can achieve.

Every day in London I, along with millions of others, benefit from the legacy left by perhaps the most remarkable generation of engineers, architects, town planners and builders the world has ever seen: the Victorians.

I walk in one of the eight Royal parks which in the middle of the 19th century were turned from the monarch’s private hunting grounds into the wonderful spaces we all can enjoy today.

Or I travel on London’s Underground, the first section of which opened in 1863 on the Metropolitan line.

Or I commute in and out to my home in Henley where the train station opened on the first of June 1857.

Or I travel from London to Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds, Glasgow, Edinburgh on a rail network which was built in 1830s, ‘40s and ‘50s.

Each of those elements has been critical to London’s success for the past century and a half. Each has been essential in making London a truly global city - a city that, unlike Sydney, has no natural advantages.

Thanks to the legacy left by the Victorians, London has been able to build its success on one key foundation stone: mobility - the ability to achieve a critical mass of people, skills, goods, creativity in one easily accessible place at the same time.

If you look at a commuting map into London it looks like the spokes of a bicycle wheel. People are able to commute from destinations 360 degrees around the centre, some as far as 20 to thirty miles away. And that is only possible because of the vision of the Victorians.

And they are able to do so from areas where they can enjoy the countryside because of another idea which while it was originally conceived in Victorian times actually took until the 1930s to deliver: the Green Belt.

So in London and Sydney we owe our predecessors, visionaries like John Bradfield a lot. They took the urban concept and made it work - and, in the process, made much of the modern world that we take for granted today possible.

That is their legacy.

But if we have been living off that legacy for the past century, what is wrong with living off it for another century? Why do we have to worry about inventing a new legacy? Surely, all we have to do is maintain the old one?

There are a number of problems with that approach.

Firstly, the legacy is wearing out.

Secondly, it can no longer cope with the level of demand being placed on it.

Thirdly, global cities like London and Sydney are becoming victims of their own success. They are over-heating.

Fourthly, the non metropolitan areas are in going in the opposite direction. They are becoming less competitive and that negative trend is feeding a politics of anger and frustration, as events in Britain, the US and, most recently Germany, have under-lined.

Let me take each of those points in turn.

The West Coast Mainline is the railway that connects London to Birmingham, Manchester and Glasgow used by a mixture of fast, local and freight trains.

It was built in the 1840s and ‘50s, not as a single line, but as a series of smaller individual lines which eventually joined up to make the West Coast Mainline. But it still has all the characteristics of those original lines.

It does not go in a straight line, or at least not for long. It twists and turns according to the whims and interests of where the original builders met least local resistance to their plans. At times it can feel like riding a roller-coaster.

And that, of course, makes the wear and tear on the track that much harder. And there is a lot of wear and tear because the demand is so high that there is, literally, not a spare train path along the route. The time for maintenance is very limited indeed.

The result was that by the 1990s not just had the track become unreliable it was also becoming unsafe - a point underlined by a series of serious accidents.

That led to a decision to launch a major upgrade. But working on a live railway proved far more difficult, and expensive, than originally thought. It caused huge disruption. The costs soared from an original estimate of £2bn to £9bn. And the upgrade was never completed.

And the railway today is still unreliable operating at somewhere between 80 and 90% punctuality.

The hard truth is that we have asked too much of the Victorian legacy. We have over-worked it. The legacy is worn out and no amount of incremental improvements are going to make up for that.

And yet that comes at a time when rail passenger numbers have doubled in the past decade, and shows no sign of slowing down.

People thought that the dawn of the digital age would lessen people’s need to, and desire to travel. The reverse seems to be happening.

Meetings have become important, not less in the digital age. As the world of physical exploitation and manufacture becomes less dominant in our economies and services more prominent so too have the importance of ideas and creativity - and that process of serendipity is easier face to face than down the line.

People want and need to travel.

And that, of course, is what has given global cities like London and Sydney their huge advantage for the past century. They are easy to live and work in precisely because they are accessible. But that very accessibility is now threatened. The virtuous circle has turned into a vicious one.

Excess demand is driving up house prices to the point where young people, service workers and public servants simply can’t afford to live close enough to their place of work. And it is not just a house price problem. The same is true of office accommodation. Big cities are pricing themselves out of the market. And this is not a problem limited to London, Sydney, or New York. It is a global trend.

At a time when the younger generation put “quality of life” higher and higher on their list of priorities cities are going in the opposite direction. Hence the increasing number of books with titles like “the global urban crisis”.

At the same time, paradoxically, other parts of the very same countries are not just feeling left behind. They are being left behind.

In part that is because the old traditional industries on which they depended have either died out, or become less reliable employers, whether it is large-scale manufacturing or mining.

And yet the new industries that could replace those jobs - whether they be in finance, creative services, or high-tech digital - depend on creating a critical mass of skills and professional services, as well as access to the supply chain and global markets that these areas struggle to develop because of poor connectivity.

So we face a future in which both ends of the spectrum lose out: global cities because they are increasingly unaffordable; non-metropolitan areas because they are becoming increasingly detached from the industries of the future.

For both the trend is only likely to get worse not better - unless we do what John Bradfield did, and do it in a way which is aligned, not just with the economic needs of our century, but the priority this generation give to all those elements that they see delivering a proper quality of life.

This is not about delivering infrastructure for infrastructure’s sake, or providing capacity relief to sustain the status quo. Doing that doesn’t address the fundamental issues. It simply delays the crunch point for a few more years.

What is needed instead is a strategy that uses investment in transport as a catalyst for a much more fundamental change; a catalyst for economic re-generation in both the metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas; but a catalyst too for re-generation of our environment to provide that quality of life that this generation rightly demands.

In other words we need to take a multi-dimensional approach, not one dimensional. But we also, like John Bradfield, need to define the outcomes we want to achieve and then build and sustain a consensus that enables those outcomes to be delivered whatever the prevailing circumstances.

No more stop/start according to the political whim of the day. Instead major strategic, expensive infrastructure projects need to build a bi-partisan consensus behind them that is capable of surviving the ups and downs of the electoral cycle because, inevitably, they take several decades to deliver - and the consensus has to last that long.

That is easier in some political cultures than in others.

In autocratic or semi autocratic cultures a government can make a decision and then follow it through, no matter what the local opposition. That is not possible, or desirable, in more democratic cultures like ours.

We have to not only persuade national governments to back and financially support our projects, but also consult at a local level.

Too often that process has been a recipe for delay and dither: consultation as an excuse for a lack of commitment either at the centre (often from Treasury ministers who are suspicious of “big infrastructure”) or at a local level where representatives can’t see past the inevitable construction impacts.

So, how to create, sustain and develop a consensus to support these kinds of strategic projects?

John Bradfield showed the way. He was clear both what he wanted to build, but also why - and then showed the perseverance needed to deliver it over a 20 year period.

We need to show the same clarity and determination in this century if we are to equip our countries are to compete in the modern world and end the vicious cycle that both metropolitan and non metropolitan areas are caught in.

If democratic countries are to remain a force for good in the modern world then we have to find a way of resolving the paradox of over-heating global cities developing alongside under-performing hinterlands. We have to find ways of relieving the pressures on the cities whilst re-connecting the areas that have been left behind.

We have to find ways to restore the physical and financial accessibility that the metropolitan areas need to guarantee the critical mass of skills, products and markets they need to survive, whilst also allowing the non metropolitan areas access to those very same factors.

That doesn’t happen by accident, or an ad hoc approach of delivering projects on a one by one basis. It needs a joined up, strategic approach: absolute clarity about the outcome, and how each element helps deliver the outcome.

A focus on the “why” before the “what”.

And a constant process of reinforcing that “why” down the long years of delivery.

And that is not a linear approach. It is a constant process of zigzagging between the big picture concept and the detail of delivery. Both are essential, but neither are sufficient on their own.

And that is the process I am going through in my work as chairman of HS2 in Britain.

High Speed 2 is the first major railway to be built north of London since that Victorian heyday. It will go from London to Birmingham before splitting into a western section to Manchester and an eastern section to Leeds.

At 345 miles, it is the biggest infrastructure project in Europe and at £55.6bn is a significant investment by the British taxpayer in the future, especially at a time of austerity following the financial crash of the last decade.

But when it was first launched as a concept eight years the emphasis tended to be on the “what” rather than the “why” - on speed for speed’s sake rather than the outcomes it could deliver: more capacity and better connectivity addressing the failings of the existing railway.

And the focus tended to be on journey times to London so reinforcing the metropolitan/non metropolitan split rather than being an answer to it.

And yet the reality is that by adding 300,000 seats HS2 will take a lot of the pressure off the existing network, and, by cutting journey times in half between not just the main metropolitan cities, but also the next level down, it will make it easier for them to access the skills, products and markets they need to succeed.

But it has taken three years to begin to turn around that first impression that it was all about speed and London rather than capacity, connectivity and the cities outside London.

The first step in doing so was to re-define our answer to the “why” purpose; to place HS2 very deliberately in a wider economic and political context. To position it as an answer to the unbalanced nature of the British economy, and the over-dominant role of London.

But to do that we also had to simultaneously think more strategically, and engage more locally. We had to stop treating HS2 as a stand-alone project, and treat it as one element in a much bigger project to re-balance Britain.

Indeed we produced a report called “Re-balancing Britain” and gave it the sub-title “From HS2 towards a national transport strategy.” That got us into trouble with the civil service because they thought it implied the government didn’t have a strategy already. They didn’t.

But we also had to start talking to, and listening to local authority and business leaders up and down the country. When we started they were sceptical seeing HS2 as just one more Whitehall led initiative.

We had to consciously switch from a command and control mindset, to engage mode. We had to listen as well as talk - and act on what we heard.

And, guess what, the project is a better project because we did so.

But not just that. Because we have that local buy-in. Because we have bi-partisan support both at Westminster and at local level the case for spending £55.6bn of taxpayers’ money is not just better understood, but also has a far deeper reserve of support when criticism mounts.

Of course we still have a long way to go. Construction starts next year and is due to run until 2033. That is a long time to sustain support for a big project, but I am increasingly confident that the political will to do so is putting down deep roots in the body politic.

The idea of the need to re-balance the British economy is more of a given than it was three years ago. The North and the Midlands have developed much more confidence in challenging the dominance of London in the national debate.

And in the wake of Brexit there is more awareness of the need to develop a coherent industrial strategy to address mirror image problems of the metropolitan and non metropolitan areas: over-heating cities surrounded by under-performing hinterlands.

Is success guaranteed? Of course not, but it is possible if we show a bit of John Bradfield’s grit and determination in sticking to our vision, as he did for the twenty years to build the harbour bridge.

BRADFIELD ORATION 2016

So, what lessons do I draw for Sydney from my HS2 experience.

We’ll fundamentally it is the same lesson I draw from John Bradfield.

It is, first and foremost, the need to think big: to think beyond the immediate.

And then it is to see infrastructure projects not as ends in themselves, but rather as means to an end. And at this time, in this era that end has to be not just to make a city like Sydney more accessible but also more capable of delivering a better quality of life who live and work here.

Welcome as the investment in the Metro and other rail investments are, they will not be enough in themselves to make Sydney stand out as a place where people who could do business anywhere in the modern digital world want to stay, work and play.

But that doesn’t happen by accident. It needs a strategy, a vision; a consensus about what needs to be done and why.

And it needs that consensus to be placed beyond the day to day political knockabout where one administration immediately stops what its predecessor decided because it “wasn’t invented here”.

It need to be bi-partisan.

Genuinely good ideas, like the cross harbour bridge, don’t come along every day. They need to be developed, given enough room to evolve as technology evolves, protected from the changing political weather.

I think John Bradfield understood that. He knew what Sydney needed as it faced into a new era.

We, too, rare facing a new era as move from a world of physical things to one based on ideas, knowledge and platforms which exist in the ether rather than being planted in the ground.

Sydney can adapt to such a world. But to do so it needs a strategy. It needs to answer the “why” question before it decides on the “what”. It needs to have a vision and fit its developing infrastructure within that vision.

That is a challenge John Bradfield met in his day. Now it is our turn.