The Manly boy who became a champion swimmer and social observer who died in war

One hundred years ago, one of Manly’s most famous sporting sons was killed on the Somme – He was Australia’s only Olympic gold medallist to die on the battlefield.

Manly

Don't miss out on the headlines from Manly. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- The navy launch that was wrecked on North Head

- The chequered history of a ship now serving as an artificial reef

- The history behind the guns at West Head

- Fear of sharks drove a council to have a barrier built at Dee Why

One hundred years ago, one of Manly’s most famous sporting sons was killed on the Somme – Australia’s only Olympic gold medallist to die on the battlefield.

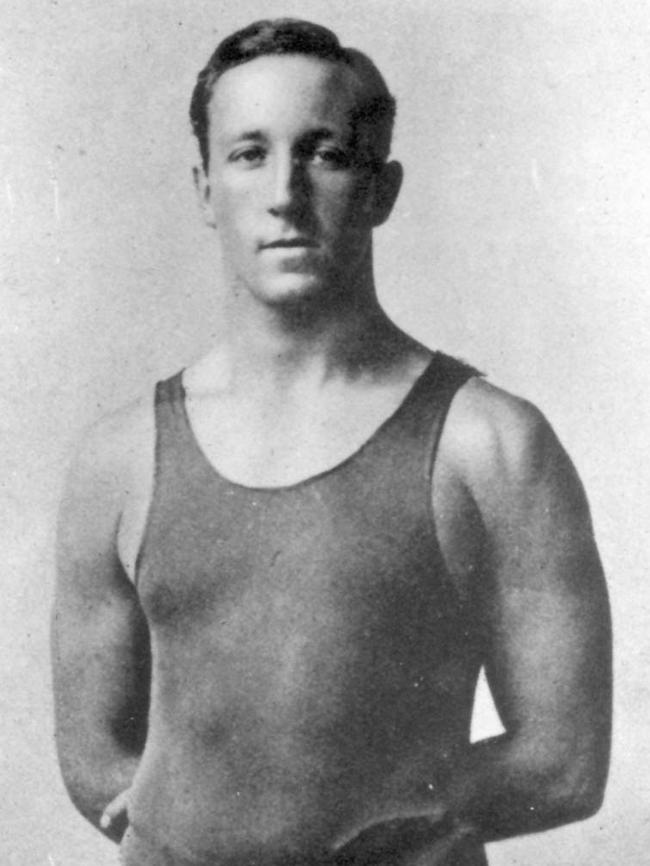

But Cecil Healy was not only a swimming champion and a highly-respected human being, he was also prescient.

He saw long before others did that there would be war in Europe and that England would be hard-put to contain Germany’s might.

What Healy couldn’t have foreseen was his own role in that war or that it would claim his life.

Healy first showed his sporting talent in 1895 at the age of 13, when he won a 66-yard race in the old Sydney Natatorium before maturing into one of the finest swimmers in the world at the time.

In 1904, aged 22, he swam an unofficial world record in the 100-yard freestyle and held six Australian titles between 1905 and 1910.

In 1906 Healy was selected for the Australian team to the Intercalated (Interim) Olympic Games in Athens.

The Intercalated Games were held mid-term, partly to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the birth of the modern Olympics and partly to repair the reputation of the Olympic movement following the ineptitude of the 1900 and 1904 Games.

Cecil’s his brother Harold was also in the team and won the silver medal in the 110m hurdles.

Cecil Healy competed in the 100m freestyle, in which he won the bronze medal, and was placed sixth in the 400m freestyle final.

Following the Intercalated Olympics, Healy won swimming championships and set records in England, Ireland, Scotland, Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands.

Back in Australia, Healy became involved in the Manly Surf Club after it was formed in 1907 and became the club captain.

Although Healy was selected for the 1908 Olympics in London, he couldn’t raise the fare and had to withdraw from the team.

It would by Stockholm and the 1912 Olympics that would provide Cecil Healy with his finest moments.

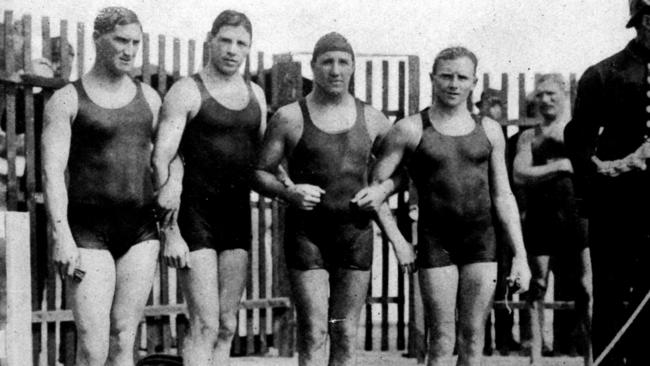

He was selected in the 4 x 200m freestyle relay and the team won the gold medal in world record time ahead of the American team.

And although he was unplaced in the 400m freestyle, Healy won the silver medal in the 100m freestyle behind the well-known Hawaiian swimmer Duke Kahanamoku.

And it was with that silver medal that Cecil Healy stamped his name in the annals of Olympic history by putting sportsmanship ahead of gold.

Kahanamoku was the favourite for the event and confirmed his status by setting the fastest time in the heats.

But Kahanamoku and the other Americans were late arriving at the pool and missed the semi-finals, effectively disqualifying themselves.

Healy clocked the fastest time in the semi-finals and with Kahanamoku out of contention, was a shoo-in for the gold medal.

But Healy knew the victory would be hollow, so he asked the officials to reconsider their disqualification of the Americans.

It has even been suggested that Healy refused to swim until the judges relented.

Healy’s persistence paid off and it was decided the Americans could swim in a separate semi-final, with the fastest swimmers going through to the final.

Kahanamoku responded by setting a world record in the semi-final and went on to win the final, edging Cecil Healy into second place and that silver medal.

Healy had sacrificed gold for glory.

But he still had the gold medal from the 4 x 200m freestyle relay and had certainly won the gold medal for sportsmanship.

Just as he had after the 1906 Olympics, Healy travelled through Europe after the 1912 Olympics and what he saw in Germany both impressed and appalled him.

In Stockholm it had been decided that the 1916 Olympics would be held in Berlin but after Healy returned to Australia, he wrote a piece for a Sydney newspaper in which he posed two questions: “Will 1916 prove to be too late? Will the storm have burst before then?”

The answer to both questions was Yes and Healy knew it.

He wrote about the vast gulf between the mindset of the English and the Germans – he had seen the growing military might of the latter and wondered aloud if the former could withstand it.

“I have travelled through Germany several times now and somehow, whenever I hear the name mentioned, I associate it with the “tramp, tramp, tramp” of soldiers. The place seems to me to be alive with them and they give one the idea of being so grim and stern. I was tremendously impressed with the power, strength and resources of the nation when I visited there for the first time six years ago. I am even more so now. On the railways and throughout the different services, military precision seems to prevail.

“It all prompts the thought that when the order is given for her army to march, Germany’s battalions will move swiftly and surely whithersoever, they are directed, without hitch or hindrance.”

Healy was right – when the order was given, German went to war and more than 60,000 Australians lost their lives, including Cecil Healy, who enlisted in September 1915.

He served as a quartermaster-sergeant in Egypt and France but wanted to be closer to the front, so he underwent officer training in Cambridge in England and in June 1918 became a second lieutenant in the 19th Battalion, sometimes called the Sportsmen’s Battalion because of the number of well-known sportsmen in it.

As well has having foreseen the war, Healy foresaw how vital America’s role would be long before those around him saw it.

In a long letter published in a Sydney newspaper, Healy wrote “I look to their inexhaustible wealth and industrial power to sooner or later turn the tide of battle in our favour.”

Healy was right, of course, but it couldn’t save him – he was killed near Mont St Quentin on the Somme, cut down by a machine gun as he led his men on August 29, 1918, just 74 days before the armistice was signed.

He was initially buried in Sword Wood, not far from where he fell, but was later interred into the Assevillers New British Cemetery, about 10km southwest of Peronne.

Healy’s death was noted in virtually every newspaper in Australia and tributes poured in eulogising his character and personality, his manner and demeanour, and his generosity of spirit.

When renowned Australian sports writer William Corbett learned of Healy’s passing, he wrote: “May the earth rest lightly upon him.”