The history behind the guns at West Head

NEAR the tip of West Head, the concrete emplacements for the guns that guarded a vital link to Sydney can still be seen, defying the years.

Manly

Don't miss out on the headlines from Manly. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- The master mariner who was a leading light behind the leading line

- Life on the edge for our wartime searchlight lads

- Bilgola Estate surveyor’s body found after going for a swim

AT the northern end of the peninsula stands an outpost of the past, a relic of a world at war and of a nation on its guard.

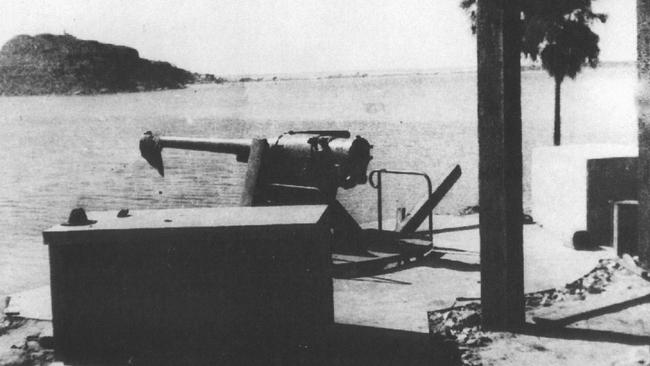

Near the tip of West Head, close to the waterline on the Pittwater side, the concrete emplacements for the guns that guarded the entrance to Broken Bay can still be seen, defying the years.

With the rising tide of militarism and rearmament in the 1930s, especially in Asia, Australia was forced to review the seaward defence of its major ports and cities.

The defence of Sydney was based around 9.2-inch batteries at North Head and Cape Banks, on which work was begun in 1936, supported by 6-inch batteries at Georges Head and Middle Head.

The system was enhanced by searchlights, anti-aircraft batteries, a submarine boom across the main arm of the harbour and by fixed and mobile radar units.

Once the defence of Sydney was in hand, attention turned to secondary ports, such as Broken Bay, which was seen by the defence authorities as a back door into Sydney and thus a weak link in the defence of the city.

The vital point that needed protection north of Sydney was the Hawkesbury railway bridge at Brooklyn that linked Sydney and Brisbane.

The top of Barrenjoey Head was considered unsuitable as the site of a battery because of the ease with which it could have been captured by raiding parties from the sea, so a site was chosen at the tip of West Head, which at the time was in private ownership but was quickly acquired for military purposes.

Plans for the West Head battery were prepared in 1939 and construction of the battery and administrative areas began in early 1941.

A railway line was laid down the steep slope from the road to a point about 20m above mean sea level and another line was laid north along the gunline.

A gantry was erected at the top of the steep railway line to load guns parts and materials on to the trolley.

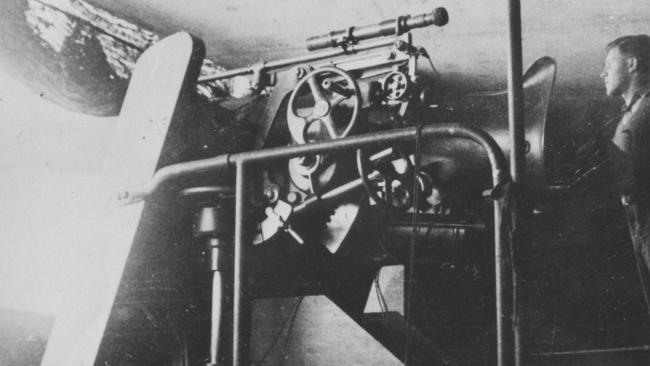

The guns were Quick Firing (QF) Mark 4 guns 4.7-inch naval guns on Central Pivot (CP) Mark 2 mountings and had a seaward firing arc from 350 to 145 degrees.

The installation of No. 2 gun, the southernmost gun, was completed on March 18, 1941, and that of No 1 gun, the northernmost gun, was completed the following day, although the final fitting-out stage took several more weeks.

A two-storey battery observation post fitted with a depression rangefinder was erected about 35m behind No 1 gun and a magazine was dug into the hillside and a duty crew shelter, or Piquet hut, was erected between the two guns.

Two coast searchlights emplacements were erected north and south of the guns.

The northernmost searchlight, designated No 31 Fighting Light, was placed within a steel-framed structure and had a seaward arc of 350 to 140 degrees, while the southernmost searchlight, designated No 32 Fighting Light, had a seaward arc of 350 to 50 degrees and was placed within a reinforced concrete structure.

On the top of the headland, a battery office, stores, quarters, ablutions and mess rooms and other buildings were erected, and a parade ground was cleared.

Although Sydney Fortress, which was based on the 9.2-inch batteries at North Head and Cape Banks, initially included all coastal defences between Marley Head to the south and Broken Bay to the north, a separate Fire Command was established for the defences at Broken Bay and the Hawkesbury River, which included the two 4.7-inch guns at West Head, two 18-pounders at Juno Head, an 18-pounder at Brooklyn and two 40mm Bofors guns at the railway bridge, as well as strategically placed boom nets and submarine indicator loops.

The battery commander and staff in the battery observation post were responsible for the selection of targets and the control of the guns and the searchlights and the role of the battery was close defence and examination until the examination role was taken over by Juno Battery in October 1943, when West Head Battery was placed in reserve.

The 2 Australian Garrison Battalion and the 7 Battalion Volunteer Defence Corps were responsible for the protection of the battery during its close defence and examination roles and the VDC personnel were responsible for its maintenance and protection after the battery was placed in reserve.

But for all its strengths, West Battery also had some glaring weaknesses, according to Hawkesbury historian Paul Boon — the railway gouged out of the cliff made a perfect ranging and siting mark for gunners on enemy ships and while coastal guns had plenty of advantages over ship-mounted guns, one shell fired from a ship could have hit the cliff above the battery and caused a landslide that would have buried major elements of the battery under hundreds of tonnes of rock.

But thankfully the battery was never forced to fire a shot in anger and after the war it was quickly overgrown and largely forgotten.

The northern most searchlight is now little more than a tangle of rusted steel, while the southern one has had its roof caved in by a falling rock, but the gun emplacements and the battery observation post remain intact.

And in recent years interest in the battery has been rekindled through the efforts of volunteers from the History, Heritage, Hunter, Hawkesbury Research (4HR) group, the West Head Awareness Team (WHAT) group and the West Head Bush Regeneration Group and, with the help of the National Parks and Wildlife Service, a track down to the battery has been reopened.