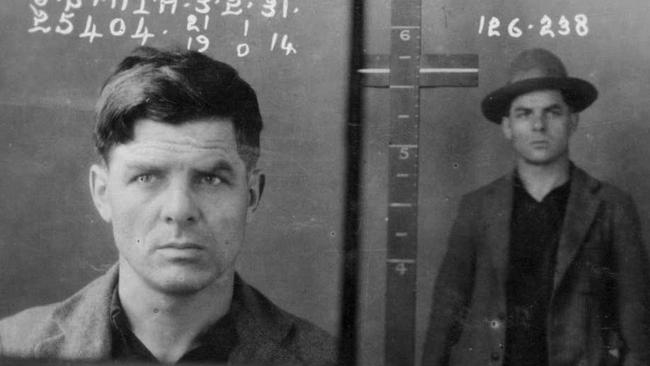

Joseph Schmidt was a better escapee than a crook

To some he was known as Joseph Schmidt but it’s hard to tell what his real name was because this infamous Sydney criminal went by many names, many nationalities and had a talent like no other for escaping. But here’s why that didn’t necessarily make Schmidt a talented crook.

- Manly to Melbourne: the murderous trail of Shaw and Skidmore

- The Manly brothers who took different paths to their 15 siblings

- Robert Hynes’ murder spree shocked Sydney in the 1970s

- How the Graeme Thorne murder changed Australia

On August 12, 1919, two police officers crept through the bush above Parsley Bay at Seaforth, looking for a man wanted for burglaries in the area.

They found their man but they also found signs of a crime far greater than the simple burglaries for which he was wanted – their quarry was in possession of materials for counterfeiting £1 notes.

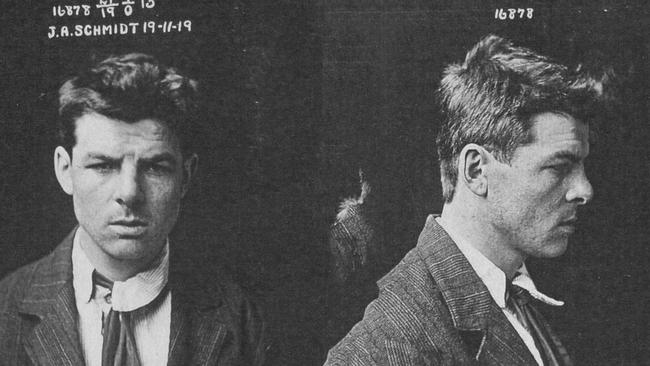

The man was Joseph Alfred Schmidt or Alfred Fritz Yackels, along with several other aliases, including James Smith, who said he was born in the Netherlands, South Africa or Switzerland, but who the authorities believed was German.

At various times he said he was born in 1890, 1892, 1894 or 1895, and had arrived in Australia in 1910, 1911 or 1913 aboard the Matilda, the St Yado or the Tulingen.

The only constant in Schmidt’s life in Australia was the heart and the letters “F.S.” that were tattooed onto the inside of his right forearm by which he could always be identified.

Whatever the truth of his name, date of birth or date of arrival in Australia, it would be fair to say that Schmidt – or Yackels – led a colourful life that often saw his name in the newspapers, including on the front page several times.

He was convicted 21 times between 1915 and 1939, often sentenced to hard labour, declared an habitual criminal twice and interned as an enemy alien during World War II but still found the time to marry twice and to father a son.

But it would also be fair to say that Schmidt wasn’t a criminal mastermind, based on the facts that he was caught so often and that some of his victims were people for whom he had previously worked and who could immediately identify him to the police.

Schmidt – to use the name most frequently used by the police and the courts – first came to the attention of both in August 1915 when he was charged with stealing three cows and two horses at Newcastle.

He was found guilty and sentenced to nine months in jail.

In November 1916, he was charged in Goulburn with malicious damage and with breaking his contract as an employee and sentenced to two months in jail.

In August 1917, Schmidt was charged with stealing a car at Woollahra and sentenced to three months in jail.

Schmidt also faced the difficulty of being a German in a country at war with Germany – in August 1917, he was convicted for being an alien and failing to report a change of address, for which he got three months hard labour, and in January 1918 he was convicted of being an alien and failing to register, for which he got six months’ hard labour.

The following year should have been a happy one for Schmidt – on March 29, 1919, Schmidt married Daisy Janvrin in St Matthew’s Church at Manly – but the year ended with him back in jail.

He had embezzled his employer – dairyman John Brimbecom of Balgowlah – and was believed to have broken into several houses in the area.

And it was while searching for him in the bush above Parsley Bay in August that year that the police found Schmidt and his wife living in a well-concealed cave that was furnished with a double bed and other comforts.

Suddenly Schmidt was front-page news because inside the cave the police found two rifles that had been stolen from a house at North Sydney and many of the makings of a counterfeit operation – 2000 pieces of the type of paper on which banknotes were printed, along with special inks, apparatus and chemicals used in photography, zinc plates and a number of negatives, one of which was of a £1 Commonwealth note.

Schmidt was charged with “having in his possession, without the authority of the Commonwealth Treasurer, certain instruments which could be used for making a Commonwealth security”.

He was sentenced to two years in jail with hard labour.

Schmidt had barely been released in late 1921 when he was charged with stealing a car at Woollahra, trying to stupefy his former employer, John Brimbecom of Balgowlah, with chloroform with intent to rob him, stealing cash from another former employer and possessing two revolvers without a licence.

While the attempt to stupefy Brimbecom with chloroform was serious, the theft of the car was farcical.

After Schmidt stole the vehicle at Vaucluse, he struggled to regulate the speed of the engine because the car’s owner had manipulated it as a safeguard against theft.

Then two young men offered to help Schmidt “fix” the car but what Schmidt didn’t know was that one of the young men was the son of the owner of the car.

The son saw a revolver Schmidt was carrying, grabbed it and then held Schmidt at gunpoint until the police arrived.

Schmidt was released on bail but after being arrested again, he escaped and lived in a cave at North Harbour for a month before he was arrested at Rose Bay.

Schmidt was convicted of the crimes and sentenced to 18 months in jail with hard labour.

Yet again, barely had Schmidt been released from jail in early 1923 than he was back behind bars, this time for two counts of larceny and two of possessing a gun without a licence.

One of the victims of the burglaries was Manly pharmacist Roger Williams, from whom Schmidt stole a microscope worth nearly £50, along with £14 in cash, while the other burglary was of the house in Manly of Ida Purves, from whom he stole cutlery, crockery and other goods.

Schmidt was sentenced to four years in jail and was declared an habitual criminal.

Tired of her husband’s behaviour, in August 1923 his wife Daisy sued for divorce on the grounds of desertion but the suit was dismissed when the judge pointed out that rather than deserting her, Schmidt had been plucked from her loving arms by the police and thrown in jail because he was a crook.

Daisy tried again in 1924 and this time her suit was successful.

Due to the laying of further charges against him, Schmidt was not released until December 1929 but within a year he was again the front page news, although not in a way that would have pleased him.

On July 16, 1930, the whole front page of the NSW Police Criminal Register, a fortnightly supplement to the Police Gazette, was devoted to informing officers around the state of the sort of man they might have to deal with if Schmidt ever came their way.

After a brief description of his appearance and a rundown of his criminal record to date, the register listed his modus operandi: “Burglar; house and shop breaker; forces windows or doors of lockup shops and dwelling-houses; breaks into the huts of Chinese gardeners during the night time, menaces the inmates with a revolver and steals their property; forces the door of a lockup garage and steals a car and uses it as a means of conveyance when committing burglaries; disposes of stolen goods and second-hand shops; offender is a dangerous criminal and will resort to the use of firearms or other violence to prevent arrest; usually operates alone.”

And just four months later, Schmidt was in the news again after he escaped from the back a moving police wagon in November 1930.

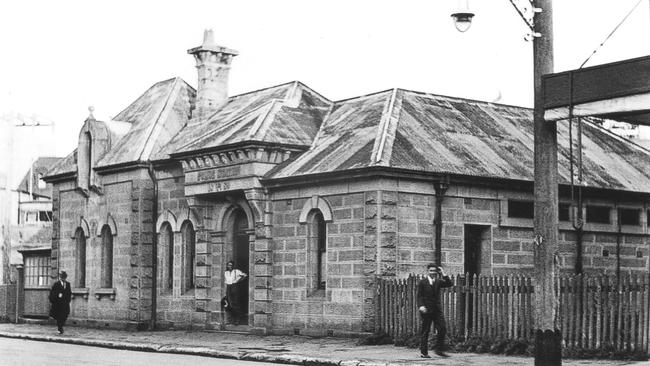

Schmidt had been picked up by the police for housebreaking and possessing a revolver without a licence and was being transported from Burwood Court to Central Police Station.

Using a sharpened piece of iron he had stolen from a toilet cistern in the Burwood police station, Schmidt prised two boards from the floor of the police wagon as it was being driven through Annandale and he and another prisoner dropped through the floor, on to the road and made their escape.

The other prisoner, John Hilton, was arrested four days later but Schmidt remained at large for more than two weeks and was only caught when he was found living in a rough hut in bushland at Hurstville.

Schmidt was convicted in February 1931, and was sentenced to five years in jail and recommitted as an habitual criminal.

After he was released from jail in 1936, Schmidt was able to avoid trouble with the law and even married again, this time to Marie Williams in December 1938, after which the couple lived at Balmain.

A son, Allan, was born in 1939 but 1939 was not a good year to be a German in Australia.

Schmidt was arrested as an enemy alien on September 4, 1939 – the day after Britain declared war on Germany, after which Australia immediately followed suit.

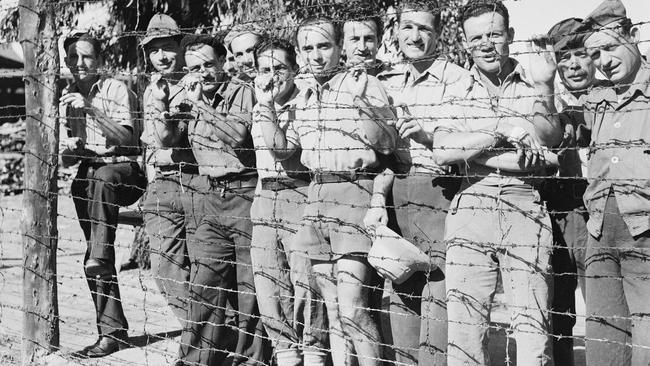

He was initially interned at Bathurst jail under Regulation 20 of the National Security (Aliens Control) Regulations and in October he was transferred to the prisoner-of-war and internees camp at Liverpool.

In late September 1939, Schmidt hired a lawyer to act on his behalf and to seek a review into his internment. His lawyer was told that Schmidt would have to provide proof of his Dutch nationality before he could be released.

In early November 1939, Schmidt wrote to the authorities, complaining that as a Dutch national, he should not be detained as an enemy alien.

By mid-November 1939, the military authorities believed Schmidt to have been a seaman who deserted ship in Australia and that the numerous inconsistencies in the information he had provided over the years were to conceal his nationality.

But on February 10, 1940, Schmidt escaped from the Liverpool internment camp, sparking the largest manhunt in Australia for many years and putting his name on page 1 of the newspapers yet again.

Police dogs were unable to follow Schmidt’s trail to freedom and it was believed he had left the camp by clinging to the underside of a sanitary wagon, which covered his scent.

During the manhunt, the military authorities thought Schmidt might have signed on as a seaman on the SS Peleus, which sailed from Sydney the day he escaped and the authorities ordered the police to search the ship at its next port of call – Albany in Western Australia.

But when the police searched the Peleus at Albany on February 20, Schmidt was not on board.

Then, on February 23 – 13 days after his escape – Schmidt was caught after a police chase across several rooftops in Beattie St at Balmain, after which he was handcuffed and lowered 10m to the ground by rope.

Schmidt had been visiting his wife and son, and the police had only gone there on the off-chance of finding him because they strongly believed he had fled interstate.

Schmidt and his wife were arrested and both were charged with having a counterfeit £5 banknote in their possession, although they were subsequently acquitted.

While being held at Long Bail jail, Schmidt applied for an interview with the NSW Police Commissioner, which was granted.

Schmidt had met the commissioner when the latter was the chief of the CIB. The interview took place on March 2, 1940, but its subject and results were not revealed to the public.

The commissioner then sent two police inspectors to interview Schmidt at Central Police Court on March 5.

They reported that Schmidt revealed a plot by himself and several accomplices to produce counterfeit £5 banknotes. The only result of the interview was that the police reported that Schmidt was “a daring, cunning criminal if released at time of war would be a danger to the community”.

Instead of being sent back to the Liverpool internment camp, Schmidt was sent to the Tatura internment camp in Victoria.

In June 1941, Schmidt appeared before the Aliens Tribunal in Victoria and claimed he was Dutch. The tribunal said that if Schmidt was Dutch, it did not have the jurisdiction to hear his objection to being detained.

In July 1941 the military authorities then decided that, based on Schmidt’s claim to be Dutch and the Aliens Tribunal’s lack of jurisdiction, then a ministerial detention order under Regulation 26 of the National Security (General) Regulations should be applied for.

On October 14, 1941, the Minister of State for the Army, Francis Forde, ruled that Schmidt should be interned under Regulation 26 of the National Security (General) Regulations, rather than Regulation 20 of the National Security (Aliens Control) Regulations.

In December 1941, Schmidt escaped from the Tatura internment camp but was captured a few hours later.

While Schmidt remained in the internment camp at Tatura, the police were keeping his wife Maria under regular surveillance and the authorities were intercepting all correspondence between them.

In July 1944, Schmidt again appealed to be released from Tatura.

This time the NSW Deputy Director of Security recommended that Schmidt be released as “we are no longer justified in detaining him for security reasons” but be placed under a Restriction Order that he be employed in a job deemed of use to Australia and live in a place determined the Deputy Director and not move from that address.

Schmidt was released from Tatura on September 7, 1944, and was entrained to Sydney, but he remained the subject of the Restriction Order.

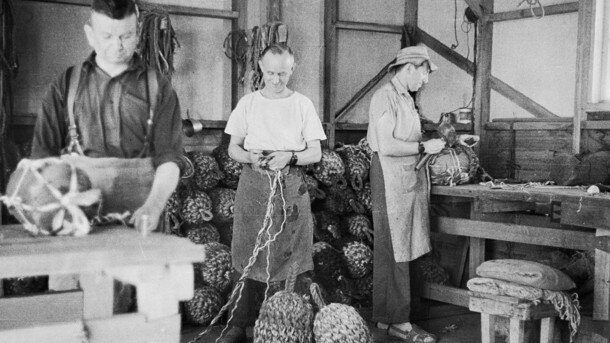

Schmidt worked as a metal worker at Redfern and lived with his wife and son at Grays Point, near Sutherland.

Schmidt’s Restriction Order was lifted on August 22, 1945, although it was not until September 8 that he got the good news.

After so long behind bars, Schmidt was finally free.

And that’s where the trail of Joseph Schmidt’s life goes cold – with no further mentions in the Police Gazette, the newspapers or the electoral rolls.

It’s as if Schmidt decided that he had spent long enough behind bars – or realised he was a lousy crook – and went straight, working at one or other of the many occupations he gave to the authorities over the years – electrician, sheet metal worker, panel beater, motor mechanic and milk carter – probably living quietly under the most common and least traceable of the aliases he had used over the years, including for one of his marriages – James Smith.