How fast ferries to Manly went from hydrofoils to jetcats and supercats

From 1965 to the present, the fast ferry service between Manly and the city has had a range of high-speed vessels, some more successful than others

- The man behind the Nazi camp at Deep Creek, Narrabeen

- How campers at Freshwater led to the suburb’s name being changed

- The bones of many vessels lie off Narrabeen Beach

For more than a century, the classic double-ended design of the Manly ferries was one of the most familiar sights on the harbour.

From paddle-steamers to oil-burners, the double-ended fleet grew in comfort and grandeur, culminating in the late 1930s with the glamorous South Steyne.

But by the 1960s the ageing ferries were losing revenue to cheaper and more convenient modes of transport and, while the large double-enders were never going to lose their place on the harbour and new ones were already on the drawing board, the Port Jackson and Manly Steamship Co (PJMSC) was forced to find new ways of attracting patrons.

The PJMSC thought it had found the answer in high-flying, high-speed hydrofoils.

For the first time, the route between Manly and Sydney would be operated by two services – a less expensive one that took a leisurely 35 minutes to do the run and a more expensive one that made the run in half that time.

The first hydrofoil was the 72-seat Manly, which was ordered from Hitachi Zosen in Japan, where it was built under licence from its Italian designers, although the engine was built in Italy.

The hydrofoil Manly arrived as deck cargo on the Kanto Maru on December 31, 1964.

It cost the PJMSC £140,000 and was Australia’s first commercial hydrofoil.

It entered the run in January 1965 but its small size and frequent mechanical problems limited its success.

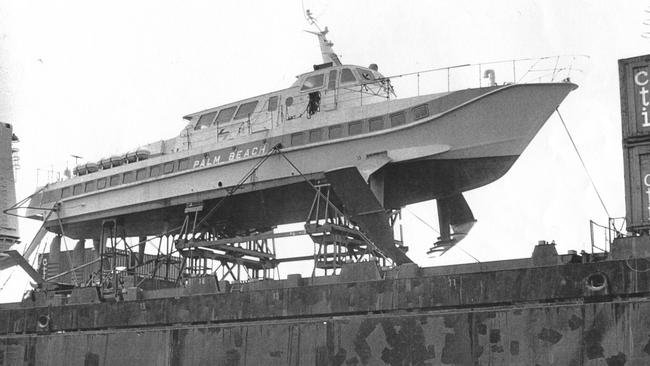

In November 1966, the 140-seat Fairlight entered service and over the next 12 years was joined by four sister hydrofoils – the Dee Why in 1970, the Curl Curl in 1973, the Palm Beach in 1975 and the Long Reef in 1978.

In 1984 and 1985, respectively, two 235-seat hydrofoils, the Manly (2) and Sydney, were added to the Manly service.

All seven of the larger hydrofoils were built at the Rodriguez shipyard in Messina, Italy.

By then the ferries had been taken over by the State Government and, while the growing affluence of the northern beaches and the novelty value to tourists made the hydrofoils commercially viable for a while, their long-term viability was never assured.

The hydrofoils were frequently out of action due to mechanical problems and were subject to a disproportionate amount of industrial problems compared with

the ferries.

The cause of the constant mechanical problems with the hydrofoils was simple – the bought-off-the-shelf vessels were designed for longer voyages than the stop-start operation of the Manly-Circular Quay run and the process of getting the hydrofoils airborne every 20 minutes placed too heavy a load on their engines and consumed large amounts of fuel.

As they aged, the operating and maintenance costs of the hydrofoils climbed and eventually the unreliability and cost of the service became a public issue. By the late 1980s, the hydrofoils were so unreliable that then-Manly MP David Hay quipped that they had missed more scheduled trips than they had made.

In 1988, Liberal Opposition politicians wooed peninsula voters with the promise that, if elected, they would introduce wave-piercing catamarans to operate the high-speed service.

The Liberals won the 1988 state election and new transport minister Bruce Baird announced that jetcats would replace the hydrofoils “within two years”.

Mr Baird was true to his word and the first jetcat, the 250-seat Blue Fin, entered service in July 1990, to be quickly followed by the Sir David Martin and the Sea Eagle, both of which seated 279 passengers.

The last of the hydrofoils was retired from the Manly run at the end of 1991.

The hydrofoils Fairlight, Dee Why and Palm Beach were sold and cut up for scrap at Homebush Bay on the Parramatta River in 1988.

The remaining hydrofoils – the Long Reef, Curl Curl, Manly (2) and Sydney were sold overseas for $3.35 million and left Sydney aboard the container ship Regine in 1992.

The first hydrofoil, Manly (1), had been sold in 1979, taken to north Queensland and renamed Enterprise but now remains on dry land, sans foils, first near Mildura and now near Kulnara.

In 2018, Englishman Andrew Heighway announced that he had bought the Curl Curl, which had been renamed Spargi, and was going to restore it and return it to Sydney, where Mr Heighway lived when he was young.

The hydrofoils’ replacements – the three jetcats – ran into mechanical trouble almost immediately – less than a year after their introduction, one of the hydrofoils had to be brought out of retirement because all three jetcats were out of service.

Between July 1990, when the first jetcat went into service, and April 1992 there were five engine fires, the result of a faulty fuel link that put the entire fleet out of service for nearly two months and cost the State Transit Authority (STA) $80,000 a week.

Another frequent problem was the jet intake getting clogged with rubbish floating in the harbour, which was easily removed from the intakes but briefly forced the vessel out of service.

The STA also ran into union hostility over several issues, including its plan to use the jetcats at night, instead of the conventional ferries, and because the public was angered by the inability of the jetcats to keep to their timetable.

Eventually the night service was established.

There were other complaints about the jetcats – that their wash was damaging boats, moorings and seawalls in Manly Cove, and that the smell of the engine fumes left shopkeepers on Manly Wharf complaining of headaches.

Despite their superiority over the hydrofoils in terms of operating performance, the jetcats were still prone to mechanical problems and high operating costs and by 1996 – just six years after introducing them – the STA was having to issue denials that it was considering scrapping them.

By 1997, when the number of operable jetcats was down to just one vessel on several occasions because of breakdowns, even the STA was admitting that the jetcats were unsuited to the short-haul Manly run and that it was considering replacing them.

Even scrapping off-peak services in 1998 could not save the jetcats and it surprised no one when then-Transport Minister Carl Scully announced in November that year that the jetcats, along with the twin-hulled inner harbour ferries, would be replaced with 12 so-called supercats.

As if to reinforce the need for their own replacement, three weeks later all three jetcats were out of service again, throwing the ferry service into turmoil.

Although there was general relief at the imminent demise of the jetcats, those in the know were disturbed by the philosophy behind the supercats – that the same vessels would be used on all runs to every wharf in the harbour, including Manly.

The rationale behind the design of the supercats was beguilingly simple – a single type of vessel that could operate from every wharf in the harbour between Manly and the head of the Parramatta River would make good economic and operational sense.

It was reasoned that, with just one type of vessel, instead of two or three, there would be an economy of scale and a more efficient use of spare vessels.

But there was just one problem – the supercats had a freeboard (the distance between the water and the top of the hull) of just one metre, whereas a freeboard of 2m is required for vessels crossing the Heads.

The supercats were also slower and seated fewer people than the jetcats and only had one door to the passenger cabin, slowing the process of embarking and disembarking passengers.

Despite this oversight, the supercats were built, began operating on the inner harbour routes and were slated to begin on the Manly route in March 2001.

But straight away they ran into problems on the Manly run – on May 28 that year, the supercat Mary Mackillop was swamped by a wave near the Heads that smashed the vessel’s plastic windscreen and drenched commuters.

The next day the supercat service was cancelled because of the height of the swell and the cancellations kept coming, leaving commuters frustrated.

Eventually Sydney Ferries admitted defeat, withdrew the supercats from the Manly run and put new engines in the old jetcats.

But the mechanical problems with the jetcats had not ended and the price of fuel kept rising, along with the cost of providing the premium service between Manly and the city.

It took until a mini-budget in November 2008 for the death knell for the jetcats to finally be sounded and the last jetcat operated on December 30, 2008.

In February 2009, the state government announced that Bass and Flinders Cruises had won the right to operate a fast ferry service between Manly and Sydney under the name Manly Fast Ferry.

The three jetcats were sold in 2009 to a Queensland-based marine brokers and consultants firm for $1.2 million.

In December 2009 – less than a year after beginning the private fast ferry service between Manly and Sydney – the state government told Bass and Flinders Cruises that its services were no longer required and that a five-year tender to operate the fast ferry service had been handed to Seaflight Ferry Services, operating as Sydney Fast Ferries.

But Bass and Flinders Cruises – operating as Manly Fast Ferry – continued to operate a fast ferry service to Sydney, using the wharf in front of the Manly Wharf Hotel, instead of the eastern side of the main ferry wharf.

So commuters now had three services from which to choose – the traditional ferry, Sydney Fast Ferries and Manly Fast Ferry.

In 2014, the state government made it known that only one fast ferry service would be able to operate between Manly and Sydney under a five-year contract, starting in April 2015.

Four companies lodged bids for the five-year contract – Manly Fast Ferry, Sydney Fast Ferries, Sealink Travel Group, which owned Captain Cook Cruises, and Transit Systems, which operated bus and ferry services in several Australian states.

The contract was won by Manly Fast Ferry and the contract was for seven years, not five.

Manly Fast Ferry then signed a multi-million contract with Tasmanian boatbuilder Incat for the supply of four new high-speed vessels for the Manly run – Ocean Wave, Ocean Tracker, Ocean Flyer and Ocean Surfer – which were followed in 2018 by a fifth vessel from Incat – Ocean Adventurer.

In December 2017, peak motoring organisation the NRMA bought Manly Fast Ferry.