How campers at Freshwater led to the suburb’s name being changed to Harbord

One hundred years ago, some of Freshwater’s residents wanted the name of their suburb changed.

Manly

Don't miss out on the headlines from Manly. Followed categories will be added to My News.

One hundred years ago, some of Freshwater’s residents wanted the name of their suburb changed.

They were concerned that the good name of Freshwater had been sullied by the boisterous behaviour of some of the young men who rented the many camps scattered around the area, mainly at weekends during the warmer months.

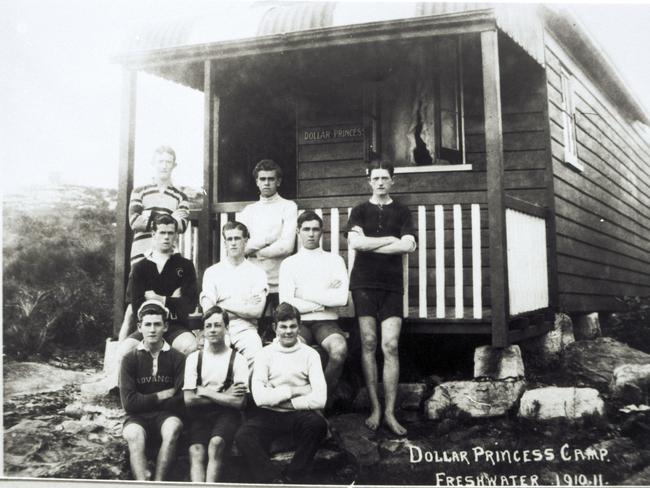

Back then, the word “camp” was applied to anything from a tent to a small three-room timber cottage.

Some of the camps were built on land owned by five people and rented for the season or the year by young men, while others were built on privately-owned land and used by the owner and their family or friends, although no doubt some of the latter were also rented to tenants.

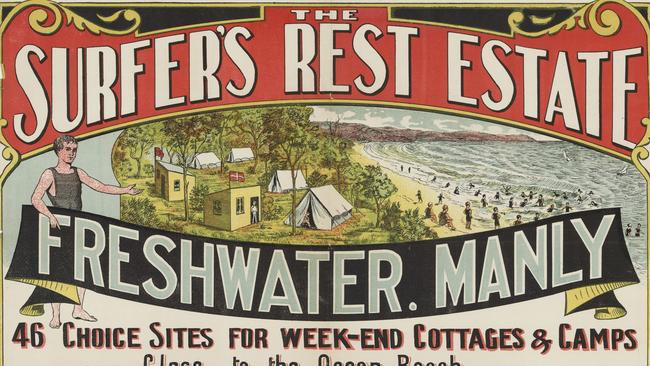

Developers contributed to the phenomenon by subdividing acreage into lots of varying size, including some that were advertised as “choice sites for weekend cottages and camps”.

All told, there were more than 80 timber camps at Freshwater.

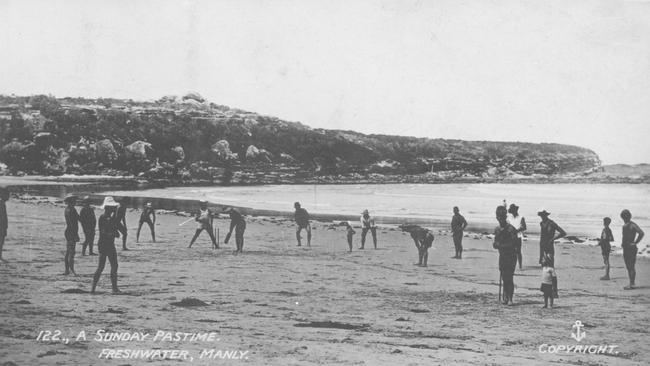

The first camps in the area were just tents pitched behind the beach for the weekend “which at night are distinguished by twinkling lights and camp fires”, as one reporter noted.

The first formal camps were erected in 1906 by Amos Randell and his future wife, Ruth Lawson, who also opened the first store at Freshwater to supply both the campers and local residents.

By December 1906 Randell had erected three camps and more camps quickly followed.

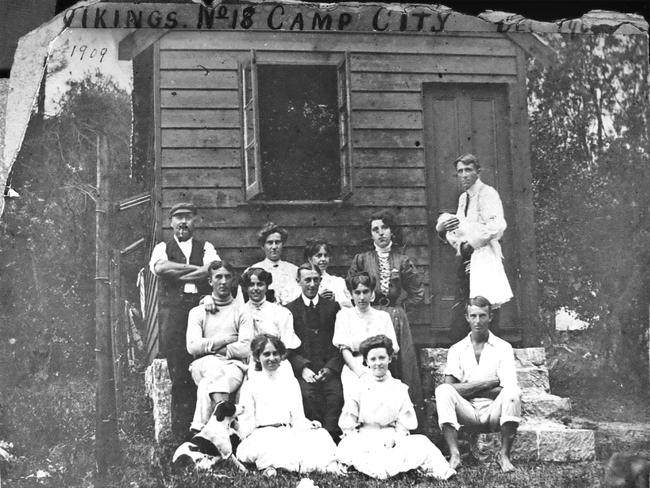

Randell’s business was called Camp City an by the time bus services eventually reached Freshwater, their destination signs read “Camp City”.

Another local man who erected camps was William Nixon, who had several landholdings in the area and who played a leading role in Freshwater society for many years.

Among the camps Nixon built were some on the high side of Undercliffe Rd, the best-known of which, at least to surfing historians, was called Boomerang.

When Duke Kahanamoku visited Sydney in 1914 and 1915, he briefly stayed in Boomerang.

Other locals who erected camps at Freshwater and rented them to tenants were a Mr Shaw, a Mr Waters and a Mrs Pember, and most were built along Evans St, The Drive, Charles St, Kooloora Ave, Moore St and Oceanview Rd.

The camps owned by Randell, Nixon, Shaw, Waters and Pember were only rented to young men and women were only allowed to visit on Sunday.

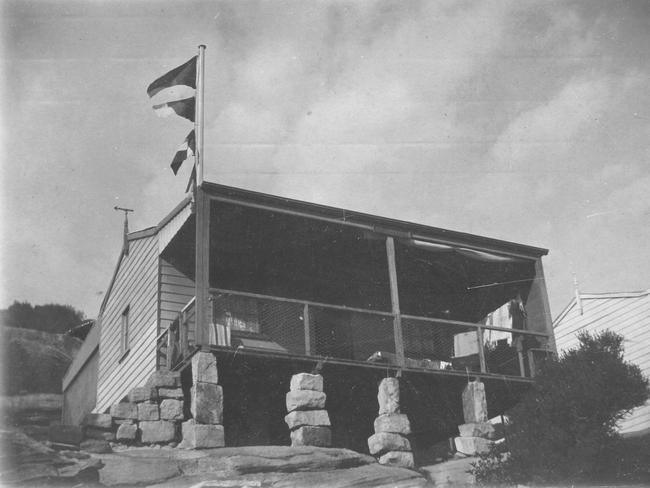

Initially the camps built for rental had timber frames and were clad in lime-washed hessian, scrim or canvas, but soon they were clad with weatherboards and fitted with gutters to catch rainwater and by February 1908, there were dozens of them, one reporter noted.

“Each camp is provided with a galvanised tank, as well as with a colonial oven.

“Six canvas stretchers are provided, rough dresser, table and forms, and the tenants make themselves extremely comfortable.”

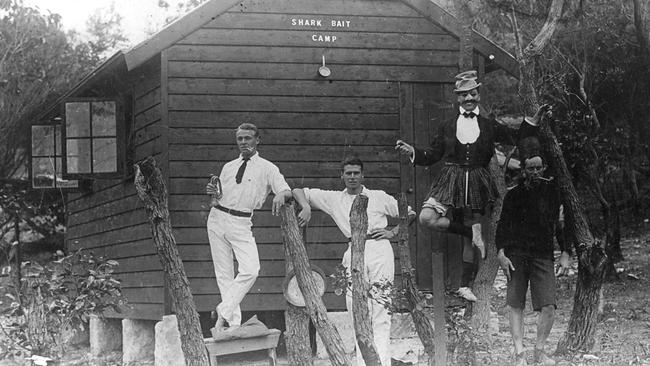

Reporters were quick to spot the sometimes weird and wonderful names that the camps.

One reporter noted two ambitiously named camps – Rawson, the name of the NSW governor of the day, while its next door neighbour was called Northcote, the name of the governor-general of the day – only for both to be trumped by a camp named Buckingham Palace.

Other names included Shark Bait, The One, The Other, Next Door, Next Door Again, Dollar Princess, Water Rats’ Rendezvous, Desolation, Thisisit, Iduno, The Millionaires, Linga Longa, Look Who’s Here, Asylum and The Ritz.

Each year, Amos Randell awarded a prize to the tenants of whichever of is camps had shown the best management and conduct throughout the season.

But while the young men were expected to behave well, especially by Randell, as early as 1910 there were complaints by residents of Manly about the bad language used by the campers as they made their way to Freshwater and sometimes the police charged young men with using offensive language in Manly.

Many of the campers joined Freshwater SLSC after it was formed in 1908 and when the club held its first carnival in February 1909, the campers held a fancy dress procession from Manly Wharf to Freshwater.

In December 1910, a newspaper reported: “Mr Waddington, secretary of the Freshwater club, visited all the camps last Sunday and secured a big haul of new members.”

In the lead-up to Freshwater SLSC’s 1911 surf carnival, one newspaper reported: “Everyone in Camp City is working enthusiastically to make the function a success.”

And while most of the campers were working men, usually from the inner western suburbs, there were a few higher flyers with their own camp at Freshwater, including noted public servant and naturalist Arthur Bassett-Hull and dual-international footballer Clarence Prentice.

Eastern Suburbs State MP Charles Oaks had a camp at Freshwater in 1924 during which time he was Colonial Secretary and Minister for Health.

Freshwater was also the destination for Boy Scout troops from the inner western suburbs who would camp in tents for two or three weeks.

In 1912, one newspaper reported: “The Freshwater surf-bathers are a pretty giddy crowd and their ‘camps’ of late have become notorious.”

Still, Freshwater retained its charm for visitors.

“Running back from the semicircular beach is a naturally beautiful valley, a fairy bushland, bounded by craggy hills,” one reporter wrote.

“In the declivity between these rocky outcrops, stretching back for a mile or more, are dotted the weekend shacks, camps, cottages, or what other name one chooses to call the two- or three-room wooden structures.

“These are the residences of the weekenders.

“Some are giddily poised on slender piles of stone or brick, others on wooden stakes, and yet others dumped down flat on a convenient nook in the rocks. “There is no building covenant over that way and the shacks are destitute of any architectural pretensions.

“The population of Freshwater is migratory.

“From Monday to Friday the place is as dead as a door nail and there are not many about except the few who reside there permanently.

“But during the long summer every Friday night sees the arrival of long streams of weekenders.

“This stream continues all Saturday morning and increases a hundredfold during the afternoon.

“It is likely that the great majority of Freshwater weekenders are quite peace-loving, hardworking, and noiseless people.

“But a comparatively small number of noisy young men and giggling young women can turn an otherwise peaceful paradise into an inferno and rightly or wrongly Freshwater has the name of being at certain times a place of fearsome noises.”

In January 1914 a group of young men camping at Freshwater were charged with using offensive language in Manly and in February 1916 three young men were charged with riotous behaviour in Manly.

Despite such incidents, camping at Freshwater remained popular and in July 1918, a block of land in Adams St that was 7.6m wide and 46m deep, described as “an ideal site for the weekend camper”, was for sale for £35.

But 1919 was not a good year for the camps at Freshwater – Amos Randell died and there was a shooting in one of the camps.

The non-fatal shooting occurred after an argument between two men who had been drinking in a camp called Brush Villa and led to the shooter being charged with attempted murder, although he was subsequently acquitted.

Although Randell’s camps continued to be used after his death, they were either sold or demolished by the time his land was subdivided in January 1924.

In September 1921, the police busted a sly-grog shop at Freshwater operating from the back of a lorry.

As one newspaper reported: “For some time past Manly has been shamed by the reports of orgies of drunkenness among women as well as men every weekend at Freshwater.

“So bad were these events becoming that Freshwater residents grew seriously alarmed.

“Visitors were wholly responsible for the scenes.

“There is no hotel at Freshwater and the police were interested to know where all the drink was coming from.

“It was hardly likely that each visitor could bring his quota along, as the quantity consumed, judging from the number of empty bottles and kegs – the disposal of these was becoming a big Freshwater industry – available every Monday morning, made it too big for individual jobs.”

In 1922, five women camping at Freshwater were charged with vagrancy, although they were acquitted.

The sensationalist Truth newspaper seized on the matter to use alliterative headlines to tell Sydneysiders what was going on at Freshwater: “Freshwater Frolics. Frisky Fellows and Flighty Fairies. Deplorable Doings in Diminutive Dens” and “How Young Girls Drift to Destruction.”

“The place is slipping badly.

“This is due entirely to the influx of mobs of undesirables, both male and female, from near and distant suburbs of the City.

“Some of the best building sites, which in the ordinary course would have been built on and the houses tenanted by decent people, have been snapped up by speculators and used to erect miserable humpies called weekend camps on.

“The whole of the hillsides are dotted with these dirty little eyesores and the natural beauty of the place entirely spoiled.”

“At weekends many of them are tenanted by dirty, drunken and depraved males and dissolute damsels.”

In early 1923, a real estate agent advertised “14 lots at Freshwater, all of them suitable for camp sites, and some of them have camps erected thereon.”

Four months later a number of female campers were charged with vagrancy but their cases were heard in camera so the outcome is unknown.

For years local residents had been lobbying Warringah Council to “clean up” the camps at Freshwater.

Some locals also wanted the name of the suburb changed to escape the opprobrium associated with some of the camps and ultimately succeeded.

The Postmaster-General agreed to the name change and on September 1, 1923, Freshwater was officially changed to Harbord.

Harbord was the name of the massive subdivision of Crown land in 1886 that covered part of Freshwater, part of Curl Curl, all of North Curl Curl and part of Dee Why.

The Harbord estate was named after Lady Judith Harbord, the sister-in-law of Lord Carrington, the Governor of NSW at the time of the subdivision and for whom Carrington Pde was named.

Not that the name change made any difference.

In February 1924, Cr Ramsay McKillop told a meeting of Warringah Shire Council about the behaviour of the campers.

“Beer flowing, trumpets blowing, fearful language loud and strong, waking people all night long, it’s not right, and it must be stepped,” he said.

The opening of the tramline to Harbord officially opened on December 9, 1925, making it easier for the campers to come and go.

Harbord residents even lobbied the Chief Secretary to establish a lockup at Harbord to make it easier for the police to suppress the behaviour of the campers but it never eventuated.

In October 1927, nine campers were charged with a string of offences including offensive language and assaulting police, and in May 1929, five female campers were charged with vagrancy.

In June 1929, there was a brawl involving nine men.

After that, Harbord appears to have settled down because there are no further newspaper reports of campers being arrested.

From the early 2000s, local residents and the chamber of commerce asked Warringah Council to support an application to the Geographical Names Board to change the name of the suburb back to Freshwater.

In public consultation, 774 voted in favour of the change and 161 voted against it.

Harbord was officially renamed Freshwater on January 12, 2008.