Coronavirus frighteningly similar to deadly Spanish flu in 1919

NSW has certainly been here before. The similarity between the devastating Spanish flu of 1919 and today’s rapidly spreading coronavirus is startling and terrifying. Thousands died.

Central Sydney

Don't miss out on the headlines from Central Sydney. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- First Northern Beaches coronavirus case confirmed

- Western Sydney medical centre treats a patient with coronavirus

- Coronavirus: What it’s like inside the nursing home in lockdown

“From a business point of view Sydney is dead. There is no life in the city. Theatres, hotels, picture shows, etc. are closed and the usually thronged streets are not the same. The wearing of masks is general.”

Besides the absence of panic buying of toilet paper, this report from the The Cessnock Eagle and South Maitland Recorder February 7, 1919 edition, could well describe the situation unfolding in cities across the globe as the coronavirus takes hold.

In fact, it refers to the dire situation as the Spanish flu cut it’s deadly way through Australia and the world at the end of WWI.

As health authorities struggle to contain the spread of coronavirus (and its impacts) it’s worth noting that the world has certainly been here before.

Spanish flu killed between 50-100 million worldwide over 1918-1919. By the time the “pestilence” was over, about a third of all Australians had been infected and 15,000 were dead.

In 1919, in the City of Sydney, 42 per cent of all deaths were from the flu.

The newspaper article goes on to praise the efforts of NSW authorities to contain the outbreak. Reported cases in NSW were at that point 73, with two deaths. In Victoria, much worse, it said.

“In Victoria the conditions are different. To date the number of cases total 1915 and there have been over 80 deaths. The new cases are reported in numbers exceeding one hundred a day and the absence of a complete system of precautionary measures is held responsible for the spread of the disease.”

How it started

The Spanish flu pandemic was one of the worst in recorded human history and came in distinct waves. The first in 1918, and then two more horribly virulent strains in 1919.

The epidemic was first reported widely by the media in Spain during mid-1918 when country’s King caught it and became gravely ill (he survived). The disease had reached England and other allied countries at the same time, but censorship rules prevented news coverage of the outbreak spreading outside of Spain. The disease then became known as the Spanish flu – but in reality, its origin has never been conclusively proven.

How it spread

Australia heard about “devastating outbreaks” in South Africa and America in September 1918. Infection was massively increased by the number of soldiers returning home from Europe after the war. By October, the disease had reached New Zealand and from there it was an almost inevitable jump across the ditch when infected passengers arrived by ship in Sydney on October 25.

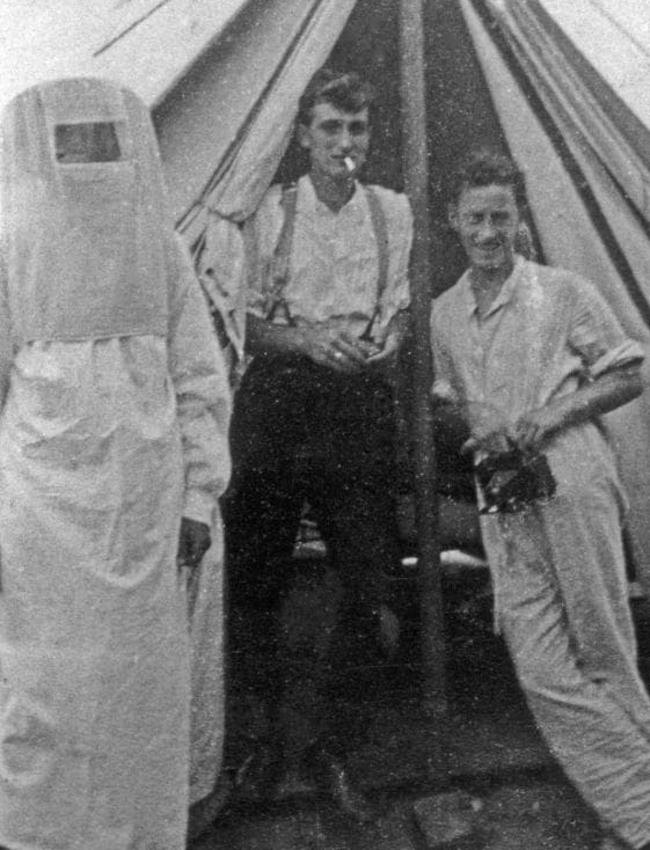

They were quickly confined to North Head quarantine station in Sydney, but, just as coronavirus is doing now, infected people were to slip through the net to carry the contagion onwards through the population.

Things got worse

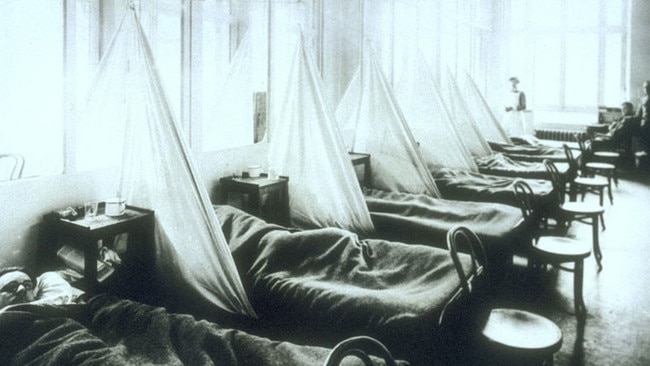

On 24 January 1919, a “suspicious case of illness” of a soldier at a Randwick military hospital was reported to NSW Health. The soldier had travelled from Melbourne by ship four days before, sharing a compartment with a civilian who was “very ill with aches and pains and a high temperature”. The soldier became ill himself on January 22 and was admitted to hospital. Within two days three nurses treating him at the hospital also became ill, and during this time, seven other soldiers who had travelled to Sydney from Melbourne were admitted with the same symptoms. Doctors visited the patients on January 27 and formally diagnosed the cases as pneumonic influenza – Spanish flu.

Control measures

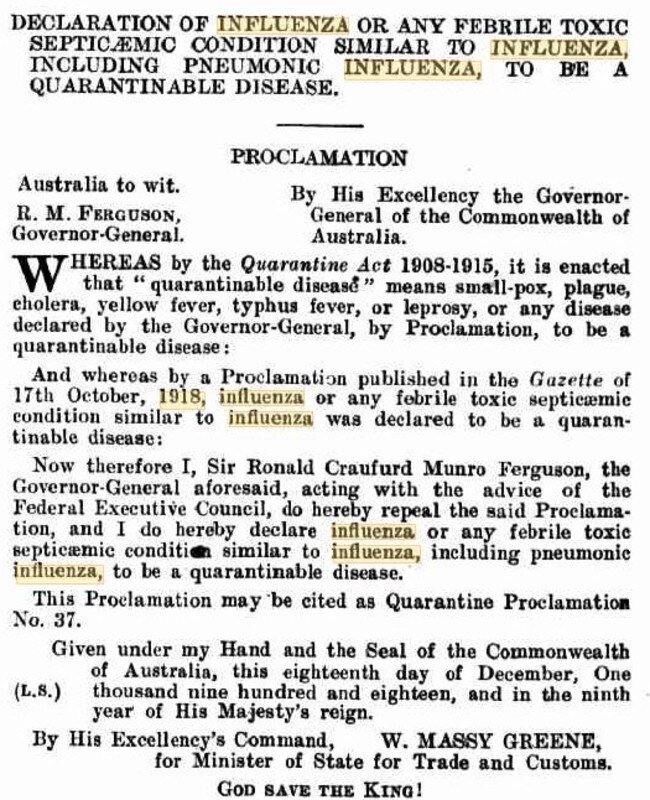

The NSW Government swung into action and reactivated a special medical council that had been set up the previous year when flu first appeared in Australia. The first of many proclamations was issued on January 28, beginning with the closure of all “libraries, schools, churches, theatres, public halls, and places of indoor resort for public entertainment”.

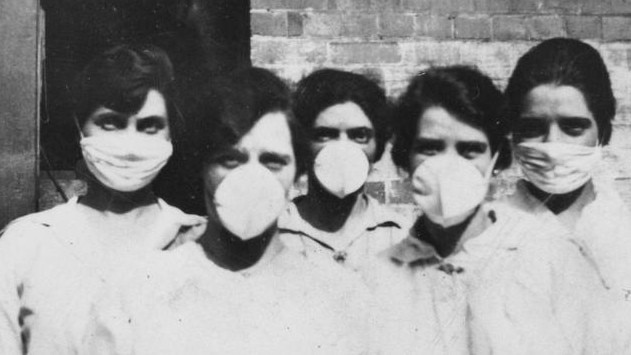

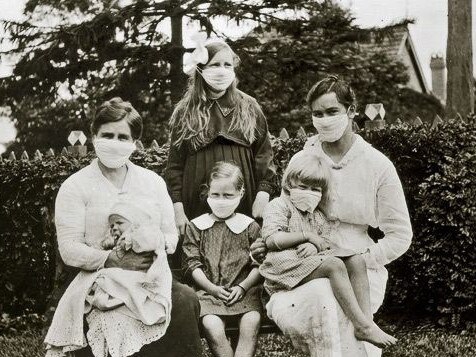

This was followed on 30 January by compulsory wearing of masks covering the mouth and nose; bans on public gatherings and restrictions on crossing from Victoria into NSW.

The rules applied firstly to metropolitan Sydney, but soon spread to cover the entire State.

Meanwhile all kinds of measures were being implemented by the Federal Government with varying degrees of success. State leaders met and agreed that once their state was infected, population movement out of the state would be banned.

But the spread of the disease continued anyhow, soon reaching towns like Corowa and Culcairn, then Wagga Wagga, Junee, and Holbrook. West of Sydney it was first reported on 10 February at Penrith, then at Liverpool, Millthorpe, Lithgow, and at Orange. Near the Queensland border it appeared at the same time as it did at Penrith (10 February), followed by Lismore, Murwillumbah, and Kyogle. The last NSW town to report the appearance of the disease was Dorrigo, on 27 September 1919

Soon racecourses and hotels were closed, and public meetings were banned. Doctors has the power to restrict the movement of individuals, especially those who had come into contact with infected patients. People who breached the new restrictions faced a hefty £20 fine.

The impacts

The impact of the epidemic were so huge that Influenza Relief Depots were set up in town halls and public schools across Sydney to assist people – many of whom had lost their jobs due to government restrictions. They took food, blankets, towels and clothing to affected households, ferried medical staff around the city and sorted out board and lodging for people who were suddenly homeless. The disruption varied from industry to industry, but the economic disruption caused was on a huge scale.

How it ended

In all there were 6,387 deaths attributed to influenza, pneumonic influenza, and pneumonia, of almost 22,000 cases reported in NSW.

Some suggest the number of people infected in Metropolitan Sydney could have been as high as 290,000.

NSW State Archives and records show that densely-populated areas suffered the highest death rates, such as metropolitan Sydney where there were 3,902 deaths (4.3% of the population), which represented 61 per cent of the total deaths in NSW.

“Mortality rates were highest for people aged 25-39. Males accounted for 3,851 or 60 per cent of all deaths, and of those, 1,522 or nearly 40 per cent, were industrial workers – equal to the combined total deaths of commercial, primary production, and transport and communication workers,” the archives record.

“In contrast, professional class male workers accounted for only 208 deaths. The poor (particularly those living in high-density ‘slum’ areas) and the working class were therefore hardest hit, both in illness and mortality, as well as financially,” they said.