Fact harder than fiction as a woman has yet to become US President

America has had plenty of female presidents on screen, but never in real life. As Kamala Harris guns for the White House, here’s why that final glass ceiling has never been broken.

US Election

Don't miss out on the headlines from US Election. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Fun quiz: what do the actors Joan Rivers, Jamie Lee Curtis, Charlize Theron, Meryl Streep and Julia Louis-Dreyfus all have in common?

They’ve all played the American President on film or TV. (Yes, even Joan Rivers – in the Australian film Les Patterson Saves The World, no less.)

The first depictions of a woman in the Oval Office go back decades: the 1953 sci-fi flick Project Moonbase posited a female president by 1970 and, on the small screen, Patty Duke portrayed the leader of the free world in the short-lived 1985 sitcom Hail to the Chief.

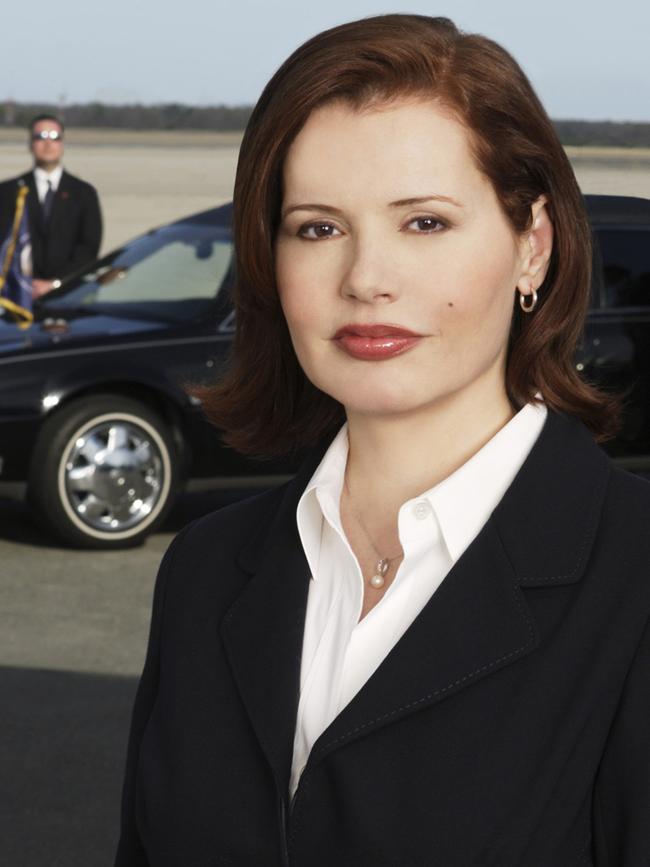

TV has shown there is no one path to the top job for women, even for those who are already Vice President. In Commander in Chief (2005), the death of a president makes it happen; in Veep (2012-19), it’s a resignation; and in House of Cards (2013-18), it’s a rather more complicated narrative involving murder, manipulation and people being extremely mean to one another.

Efforts going back decades

But in real life, getting a woman to break that final and ultimate glass ceiling has proved arguably even more challenging.

While dozens of other countries have voted in their first female leaders over the past seven decades (a club that Australia joined back in 2010 with the election of Julia Gillard), progress in the US has been slow, despite more than a century of women having the vote.

And it’s not just about the White House; just 28 per cent of the current Congress are women, and 16 of the 50 states have never once elected a female governor, including some that you might possibly expect, like California and Illinois.

“America has traditionally lagged other democracies when it comes to the representation of women in politics,” said Professor Ben Reilly from the United States Studies Centre.

The efforts go back decades. Margaret Smith sought the Republican nomination for the presidency in 1964 and Shirley Chisholm (the first black woman elected to Congress) did the same for the Democrats in 1972, but both campaigns drew little support – and, in the case of Chisholm, several death threats.

The first woman to be picked for a ticket by a major party was Geraldine Ferraro, nominated as vice president by the Democrats in 1984, but after the failure of that campaign (headed by Walter Mondale), it would be 16 years before another woman put herself forward to be nominated.

That was Elizabeth Dole, who sought the Republican endorsement in 2000; she was followed by Carol Moseley Braun, who threw her hat into the ring for the 2004 Democratic presidential primary.

In 2008, the Republicans fielded their first female vice presidential candidate in Sarah Palin, while Hillary Clinton gunned for the Democratic nomination. Both campaigns proved unsuccessful.

Women have continued to be a presence in the Republican presidential primaries, with Michelle Bachman putting her name forward in 2012, Carly Fiorina doing so in 2016, and Nikki Haley giving Donald Trump a run for his money in 2024.

Activity on the Democrats side has been more robust. Hillary Clinton may have lost her bid for the presidency against Trump in 2016, but her candidature helped inspired a new generation of women in 2020. Besides Kamala Harris, the field of women vying for a spot on the ticket included the senators Elizabeth Warren, Amy Klobuchar and Kirsten Gillibrand, the author Marianne Williamson and Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard.

Hillary Clinton’s cautionary tale

With Harris now hitting the swing states hard as the Democratic nominee, but struggling to outpoll Donald Trump, even falling behind according to some surveys, the prospect of America finally getting a female president seems tantalisingly close, but far from assured.

For many, that sounds like 2016 all over again.

Clinton invoked her own experience as a cautionary tale in her speech at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in August.

“The story of my life and the history of our country is that progress is possible, but not guaranteed,” she said. “We have to fight for it and never, ever give up.”

But she expressed optimism, too.

“Something is happening in America; you can feel it. Something we’ve worked for and dreamed of for a long time,” Clinton said.

Professor Reilly said the struggle to get a female president reflected something intrinsic to America’s politics.

“It’s a political system that’s very hard to enter. It’s very hard to change,” he said.

“The two big parties have done everything they can to make sure they don’t get any challenges from smaller parties. It’s a very locked-up political system in many ways, and that’s probably meant that it’s been hard for women.

“Twenty or 30 years ago, if you had asked people if there would be a woman president by 2024, people would have said ‘Yes, surely,” Prof Reilly said. “But it still hasn’t happened.”

Those writers and filmmakers who envisaged female presidents all those decades ago were

“ahead of the curve,” he said, but it remained to be seen if that dream of a female president will come true in 2024.

Or, as he put it: “Life imitating art, finally”.

THE PREVIOUS CONTENDERS

GERALDINE FERRARO

Former schoolteacher and lawyer Geraldine Ferraro became just one of 17 female members in the then 433-seat House of Representatives when she won her New York Congressional district race in 1978. But she rose quickly through Democrat party ranks, and when it became known in 1984 that the party’s presidential candidate Walter Mondale was keen to select a female running mate, she became an obvious contender. But the ticket fared badly against Ronald Reagan, winning just 40.6 per cent of the popular vote. During the campaign her husband’s property development business generated some negative headlines, and post-election it was revealed the addition of a woman on the ticket had only led to a modest increase in support from female voters. She made a couple of unsuccessful bids to return to politics, but stayed in the national eye as a political commentator, author, and the US Ambassador to the UN Commission on Human Rights. The mother of three died of myeloma in 2011, aged 75.

SARAH PALIN

Chosen by the Republican candidate John McCain as a potentially game-changing vice-presidential pick in the 2008 election, Sarah Palin electrified party supporters with her unapologetically Christian and pro-life, pro-gun and pro-hunting positions. The mother of five’s introduction to the spotlight at the age of 44 capped off a meteoric rise: she was city councillor of Wasilla, Alaska, by the age of 28, mayor by 32, and Alaska’s first female governor at the age of 42. But a series of disastrous gaffes during the campaign – she mixed up North and South Korea during a radio interview – fed a perception she was a policy lightweight, and the McCain/Palin ticket picked up just 45.7 per cent of the popular vote at the election, despite early high poll numbers. After the loss, Palin continued to be an influential figure in the conservative Tea Party Movement, the broader Republican Party, and via TV talk shows. She attempted a political comeback in 2022, running for a seat in Congress, but bombed badly.

HILLARY CLINTON

The push to get a woman in the White House advanced a long way – but not all the way – in 2016 when Hillary Clinton headed the Democratic ticket. She received 2.8 million more votes than Donald Trump, but won only 227 electoral colleges compared to his 304. It was a bitter blow for Clinton, who had decades earlier added policy responsibilities to the role of First Lady, first when husband Bill was Governor of Arkansas (1979 to 1981, and then 1983 to 1992) and later when he was US President (1993 to 2001). She stepped out from his shadow in 2001, becoming a Senator for New York, and held that post until 2009. She fought to be the Democratic nominee for president in 2008, losing to Barack Obama; after he became president he appointed her Secretary of State. She came to the 2016 election well-known and well-qualified, but not necessarily well-liked, and questions over her use of a personal email server while she was Secretary of State dogged her campaign. Since that loss, the mother of one has remained an influential voice in Democratic politics; together with Bill, she was one of the first senior party figures to back Kamala Harris when Joe Biden dropped out of the race for the presidency.

KAMALA HARRIS

No woman has been elected to a higher office in the United States than Kamala Harris, Vice President to Joe Biden since 2017 – and as the daughter of a Jamaican father and Indian mother, her election to that position represented other firsts, too. She spent some 20 years as an attorney and prosecutor in San Francisco, before a six-year stint as Attorney-General of California (2011-17) and then a term as Senator for California (2017-2021). She announced her candidacy for the Democratic nomination for the presidency in early 2019 but dropped out by year’s end, only to return to the frame months later as speculation intensified that Joe Biden was wanting a woman as his pick for vice president. He named her as his running mate in August 2020, and the pair won a convincing victory over Donald Trump, winning 306 electoral college votes. Critics says she has been underwhelming as Vice President, with few policy achievements, and prior to Biden’s withdrawal from the 2024 race it looked as if the Democratic nomination could end up as someone else’s; but her candidacy gained immediate momentum as soon as Biden dropped out, and within days it became apparent nobody would be challenging her. Polls suggest the November election will be tight, but Harris – stepmother of two, and partner to lawyer Doug Emhoff since 2014 – has a real chance to become the first woman to become President of the USA.