As Australia prepares to mark 75 years since the end of WWII, Warren Brown looks at the war, its importance and its grim legacy. TODAY: PART THREE

In September 1939 three uniformed Australian police officers stood on the beach at Saibai Island in the Torres Strait north of Queensland. On the horizon a lone canoeist eventually paddled into view, his canvas kayak sporting a swastika pennant fluttering defiantly from the bow.

The young sailor’s name was Oskar Speck, a German electrical subcontractor who – when his business collapsed in 1932 – decided to throw his kayak into the Danube and paddle away for an adventure. In the following seven years Speck paddled some 50,000km deciding to keep going until he reached Australia.

PART ONE: Incredible ways WWII shaped your world

PART TWO: How Hitler played Aussie PM

Becoming something of a celebrity back in Germany and a pin-up boy for the new Nazi government installed after his departure, his wish had eventually come true and he was now in Australian waters.

As he brought the kayak up to the beach, the three policemen moved forward to congratulate him on his monumental achievement. They were then obliged to inform him he was under arrest as Australia had just declared war on Germany and he was now an enemy alien. Speck would spend the entirety of WWII in an internment camp.

Adolf Hitler’s swift and brutal invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 instantly illuminated the futility of British and French policies of avoiding war through appeasing a dishonourable Nazi Germany.

Indeed, on Monday 4 September 1939, Australia’s new Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced to an anxious nation in a radio broadcast “It is my melancholy duty to inform you officially that, in consequence of a persistence by Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her, and that, as a result Australia is also at war.”

And it didn’t take long – only hours after Menzies delivered his speech, the gun battery at Fort Nepean at the mouth of Port Phillip Bay fired a shot across the bow of what they perceived to be a German freighter trying to escape into open waters. As it turned out the vessel was Australian – the SS Woniora – but the shot had the desired effect in bringing the ship to an immediate stop.

The government moved swiftly – as a result of months of careful surveillance the following day Sydney police began rounding up prominent Nazis and enemy aliens to be interned in prison facilities in regional NSW.

The Press was next to be clamped down, with the announcement of immediate censorship for radio and print for the duration of the war. Reluctantly accepting this imposition, an editorial advised caution – ‘We are fighting to defend democracy on distant fronts. We must not in the process lose it at home.’

But the new censorship laws were pushed even further – all communications by telegraph, mail and telephone were now subject to suppression.

Prime Minister Menzies announced the creation of a Second Australian Imperial Force (the First having served during the Great War of 1914-18), a new volunteer division of 20,000 recruits to be known as the 6th Division. Further they would gradually call up the entire militia force – what we would now call the Army Reserve – some 80,000 men.

But recruitment drives, censorship and firing shots across ships’ bows were hardly different to the old-world mobilisation for The Great War some 25 years before. Simply, 1939 was not 1914.

Technology was the key as the Prime Minister foretold, ‘that in this war, air power might be the deciding factor’ yet in 1939, the Royal Australian Air Force was not in great shape with a total of 246 primarily obsolete aircraft.

Menzies subsequently announced the implementation of the Commonwealth’s Empire Air Training Scheme, whereby Australian pilots, observers, wireless operators and gunners would be trained in Canada producing ‘an air force on a scale that was literally unprecedented’.

The idea in effect was to build a massive, multi-national Commonwealth air force comprising of airmen from Britain and the Dominions – in all some 28,000 Australians trained through the scheme in Canada, Australia and Rhodesia.

Then in a controversial, but hardly unexpected move, in October 1939 the Menzies government introduced conscription for all single males turning 21 in the year ending 1 July 1940, the purpose being to keep up numbers within the part-time citizen forces to a functioning level. Conscription had been a divisive – and unsuccessful – proposition during WWI. Unsurprisingly Menzies’ announcement outraged trade unions, furious he had recanted on a pledge by previous Prime Minister Joseph Lyons there would be no conscription for service at home and abroad.

Intended to fight alongside the British Expeditionary Force in France, the 6th Division sailed for the Middle East to continue training en route, but the whirlwind German blitzkrieg cornering 360,000 British and French troops on the beaches of Dunkirk, saw France defeated before the Australians were even ready.

Yet the invasion of France beginning in the summer of 1940 was not conducted by Germany alone. In the last two weeks of the offensive, Italy – Germany’s Axis partner – under the authority of the Italian Army’s Commander in Chief Benito Mussolini, declared war on France commencing several attacks in the Alps with the French poised to counter attack.

As an ally of France, Australia announced it too was now at war with Italy yet it would not be long before Australians and Italians came face to face.

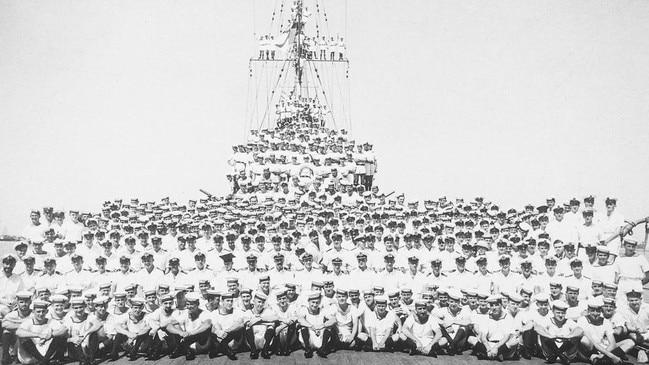

In the Mediterranean a month later, the Royal Australian Navy’s light cruiser HMAS Sydney, accompanied by a small force of British destroyers, encountered two Italian cruisers northwest of Crete, which then attempted to escape. As it transpired one of the Italian warships was the Bartolomeo Colleoni – one of the fastest cruisers in the world – yet in the ensuing engagement the Sydney was able to close the range and fire a round into the Colleoni’s engine room immobilising the ship. The disabled Colleoni was now an easy target for the accompanying British destroyers, which swiftly sank her, rescuing 545 of the ship’s complement.

At home, everyday Australians were starting to feel the pinch of increasing wartime intrusions. Pressure to swell the numbers for compulsory military training in the Australian Citizens’ Forces now saw the inclusion of unmarried men aged up to and including 33 years.

In NSW a rush on hording petrol began with the introduction of fuel rationing, panic-buying creating queues of cars for kilometres.

In the first half of 1940, three more infantry divisions were raised and two deployed to the Middle East – the 7th and 9th – the 8th Division temporarily diverted to Malaya at a British request to reinforce Singapore.

In the skies over England, the Battle of Britain was fought as a last stand to stop an imminent German invasion – Operation Sealion. Reichmarschall Herman Goering believed the Luftwaffe – with almost twice the number of aircraft and aircrew – could wipe the RAF from the skies in just four weeks.

The turning point came on Sunday 15 September 1940 when RAF fighter command scrambled 24 fighter squadrons to intercept a massive formation of German aircraft. Some 300 Spitfire and Hurricane fighters were mustered, defeating the Luftwaffe and preventing the German invasion – 35 Australian pilots took part.

In September a staggeringly-sized Italian army of 250,000 commenced an invasion of Egypt – then a British protectorate – in an attempt to take hold of the Suez Canal, but ground to a halt after a week, digging in only 80km across the Egyptian border.

The Australian Army’s first experience of action in the Western Desert was as part of Operation Compass – a spectacularly decisive counter-attack fought by Commonwealth forces that chased the Italians out of Egypt and along the North African coast.

The 6th Division was given the task of attacking the strongly held fortress at Bardia in Libya – capturing the fort on the second day and the Italian garrison surrendering on the third. Some 40,000 Italian soldiers were taken prisoner.

DON’T MISS: Warren Brown’s exclusive series continues this week

• ‘Stories of Service’ video courtesy of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs