As Australia prepares to mark 75 years since the end of WWII, Warren Brown looks at the war, its importance and its grim legacy. TODAY: PART TWO

Australia’s twenty year-long road to world war in 1939 took many turns, but its course could only arrive at one terrible destination.

The years between WWI and WWII were tumultuous, unsteady and confused.

Australia – foundering in the aftermath of the Great War of 1914-18 in which it saw 60,000 of its young men killed – was then tipped into the catastrophe of the Great Depression – the worst economic crisis the world had ever known.

PART ONE: Incredible ways WWII shaped your world

PART THREE: Ordinary Aussies answer call to arms

Yet the nation’s political, economic and social climate was somewhat different to that of post-war Europe and the United States – Australia harboured its own unique views and concerns that are perhaps relevant today.

Ever since European settlement, there had been an underlying dread among Australians that remained a live possibility – the terror of being abandoned by Great Britain.

Australians had always been mindful their country was in reality a vulnerable, sparsely populated island-continent bobbing about between the Indian and Pacific Oceans – as far from any British military assistance as it could possibly be.

Until the Federation of the states in 1901, Australia had been a divided group of bickering, individual colonies independently vying for Britain’s attention. But there was one thing the colonies – and later the states and territories agreed upon – the realisation that Australia would be next-to-impossible to defend against a malevolent invader – Japan.

Japan had in fact been an ally to Great Britain and Australia during WWI – indeed, in 1914 a Japanese warship escorted the troop convoys carrying the Australian and New Zealand soldiers who would ultimately land at Gallipoli.

But Australia had been distrustful of Japan’s military prowess as far back as 1904 when Japan won a convincing naval victory over Russia in the Pacific – the first Asian power in modern times to defeat a European adversary certainly came as a shock to many Australians.

By the 1930s Japan’s plans to create an indomitable battle fleet were well underway and despite attending obligatory international armament reduction treaties – the Japanese navy began to concentrate on building warships of extraordinary size and superiority, culminating in the construction of the fearsome super-battleships Yamato and Musashi – the largest warships of WWII.

To build such monumental weapons required vast amounts of raw materials such as iron and coal – something the tiny islands of Japan did not have – but Australia directly to the south did.

Nevertheless Great Britain assured Australians they were perfectly safe – in the 1920s there had been a plan devised known as ‘The Singapore Strategy’ whereby the establishment of a fortress-naval base in Singapore equipped with large calibre guns would allow a Royal Navy fleet to strike out and destroy any threat in the western Pacific. Nevertheless Japanese incursions into China were cause for considerable concern and Australia looked on nervously.

Yet there was another threat Australians feared – and not from an intruder, but from within – the insidious all-pervading hand of European communism.

Australia like the rest of the British Empire was aghast when Communist revolutionaries executed the Russian Royal Family in 1918, and the fear a similar uprising might befall the British monarchy destroying the Australian way of life loomed large in the minds of pro-British loyalists.

Nervous communism was being imported by Russian refugees arriving in Australia, in 1919 the Federal Government invoked The War Precautions Act banning the flying of the socialist red flag, resulting in what became known as the Red Flag Riots.

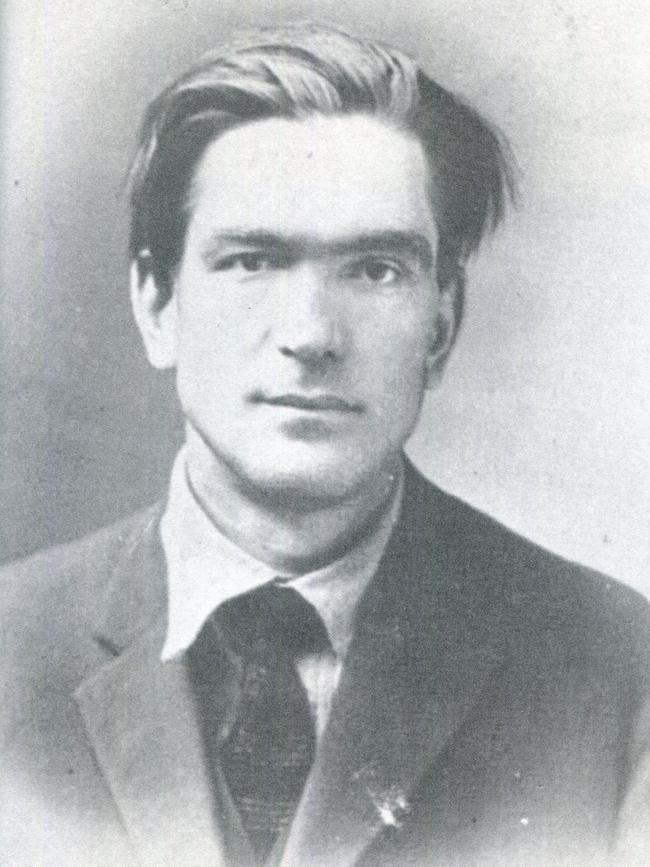

Having arrived in Brisbane Captain Alexander Zuzenko, a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary, led a protest against the ban resulting in a 7000 person riot between communist sympathisers, angry British loyalists, ex-servicemen and mounted police armed with rifles and bayonets. In the ensuing clash at least 100 rioters were bayoneted.

The Great Depression of 1929 brought with it even further uncertainty – the controversial and radical agenda of NSW Labor Premier Jack Lang during the early 1930s caused alarm among conservative Australians who believed the nation’s political stability was under threat from secret – and armed – communist groups.

The result was the emergence of well-connected clandestine anti-communist and sometimes paramilitary organisations largely made up of ex-servicemen ready to take up arms and ‘step in’ in case of a communist uprising – organisations such as the Old Guard in NSW, at its peak boasting a membership of 30,000.

Since the end of The Great War, many Australians perceived there had been a critical breakdown of not only social conditions but moral decline as well, and a sense of order needed to be restored.

A far as some were concerned, one only had to look at what was taking place in Italy and in Germany for inspiration – not only had these nations risen from the ruins of WWI, they were strong, decisive governments, flourishing progressively and economically, rallying their people together, creating work, introducing order – but more so – they were vehemently anti-communist.

During its infancy everyday Australians took little interest in European fascism, dismissing Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini somewhat as figures of fun, but the charisma and growing achievements of these rising international stars began to intrigue those in political circles.

Such was the allure of these new, modern regimes – with their pageantry and nationalistic fervour – numerous Australian politicians ventured to Europe to see for themselves – among them pacifist-leaning Prime Minister Joseph Lyons (1932-39) who actually secured a meeting with Adolf Hitler, which to his disappointment was cancelled at the last minute.

Nevertheless Lyons twice met with the next best thing, Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini, in 1935 and 1937, the dictator offering the PM and his wife Enid free first-class travel from Naples to New York aboard the state-owned ocean liner Rex – an offer they accepted.

With tensions rising in Europe, the anti-war Australian Prime Minister envisaged himself as some sort of mediator whose personal relationship with Mussolini could broker good relations between the dictator and the British Empire – the wily Mussolini giving Lyons a message to pass on to British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, ‘Tell the British government I want peace.’

Indeed, the possibility of another global war was the great fear – Lyons and his Attorney-General Robert Menzies were subscribers to Chamberlain’s appeasement approach toward the fascist leaders.

And so Prime Minister Lyons was outraged when H.G.Wells – author of War of the Worlds and The Time Machine – while speaking in Sydney, described Hitler as a ‘certifiable lunatic’ and Mussolini as a ‘renegade socialist’, the pair labelled ‘criminal Caesars’. The Prime Minister lambasted the author for ‘insulting a friendly head of state’ and that ‘Germans and Italians must not think HG spoke for all Australians’.

Yet Joseph Lyons had been well and truly played and by the late 1930s Hitler and Mussolini’s genial facade had been shattered, revealing to the world the monsters they really were.

Aggressive German and Italian expansionism, the brutal Kristallnacht pogrom of 1938, the rumours circulating about the persecution of the Jews – suddenly woke Australians to the reality of the modern world. Australian politicians who had once blithely offered praise for Hitler and Mussolini now backtracked at a blinding pace – now vociferous to the public in their condemnation of such vile autocrats.

On April 7 1939, the day Mussolini commenced his invasion of Albania – Joseph Lyons passed away from heart complications, the first Australian Prime Minister to die in office.

Within five months the world would be once again in a world war.

DON’T MISS: Warren Brown’s exclusive series continues this week

• ‘Stories of Service’ video courtesy of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs