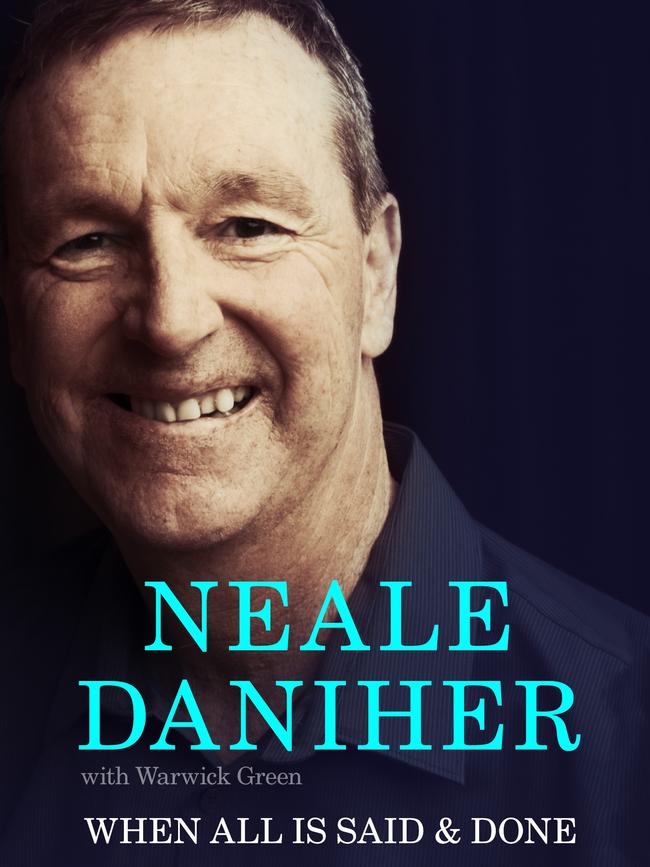

Neale Daniher is writing down his thoughts, his fears, his good times for the sake of his children and grandchildren. In this edited extract from his book When All Is Said & Done, the footy legend takes us inside his battle with Motor Neurone Disease.

Is this it?

Is this how it ends?

Slumped in a nondescript chair in the emergency ward of a Canberra public hospital, watching the thin red hand on the clock face ticking down the seconds to 6am?

I can’t breathe.

For the thousandth time tonight I feel like I’m choking for air, like I can’t draw any oxygen into my lungs.

WHEN ALL IS SAID AND DONE PART 2

It feels like those panicky moments after someone crashes into your ribs on a football field, and you curl up on the turf, winded, your mind scrambling to make sense of what’s happening to you.

But this is different to a few harrowing seconds in the hands of the trainers — I’ve been stranded like this for hours, propped up here on this chair throughout the night.

The sun is starting to creep above the horizon.

I can’t remember the last time I was up until dawn — it was probably back in my university days.

But now I’m plunked here in the emergency ward with tubes up my nostrils, staring at a flimsy blue plastic curtain and a toilet that’s tantalisingly out of reach.

Whenever the percentage of oxygen in my lungs drops below a certain level, the machine I’m hooked up to begins beeping like it’s telling the nurse in a TV drama that the patient is in real trouble.

I’d tried to clamber onto the bed next to me to lie down, but it had only made matters worse. I can’t sleep.

Now all I can do is sit here, helpless, watching the clock, hoping that life will get better, when I know it’s inevitably going to get worse.

The seconds keep loudly ticking away and my mind is working overtime.

I’m thinking about my family, about my wife, Jan, and my beautiful children, Lauren, Luke, Rebecca and Ben, and all of the gleaming memories they have given me.

I’m thinking about their futures, and about how there will be grandkids I will never get to know.

How will those kids picture their grandpa in their imaginations?

Will I be more than their grandfather who died of a cruel incurable disease?

Will my grandkids wonder what kind of man their grandfather was?

Will they wonder what he believed in?

I’m not fussed about what they will make of my time as a footballer or an AFL coach or even as a campaigner for Motor Neurone Disease.

I don’t care about a legacy, but I do care about what kind of people they’ll grow up to become.

I wish I could be there to help them make their way in the world, but I won’t have the chance.

I would have given anything to wrap an arm around those grandkids as they sat on my knee. There are things I’d love to pass on to them, life learnings I would have enjoyed sharing.

There are stories I’d like to tell them about growing up on a remote farm, about going away to boarding school, about life lessons to be gained from team sport, on and off the field.

I would love to explain to those kids that I believe there are a million ways to live a good life.

I would tell my grandkids to live life to the fullest, regardless of the difficulties that are thrown their way.

Don’t make excuses, I’d say.

Never play the victim.

IN A CANBERRA HOSPITAL

Anyway, there I was in a Canberra hospital emergency department at dawn. I hadn’t seen that particular hospital stint coming my way.

Motor Neurone Disease (MND) had already conspired to slur my speech and had left me with wiry arms and palsied fingers that didn’t work too well, but it hadn’t got hold of my legs yet and I still felt strong.

Jan was laid low by the effects of a nasty flu and was too crook to join me at an evening function, the Parliamentary Friends of the AFL reception on August 14, 2017.

But she helped me get dressed and whacked on my tie. I was starting to feel a bit tight in the chest and could hear a slight rasp in my breathing.

‘I hope I haven’t picked up your bug,’ I growled at Jan.

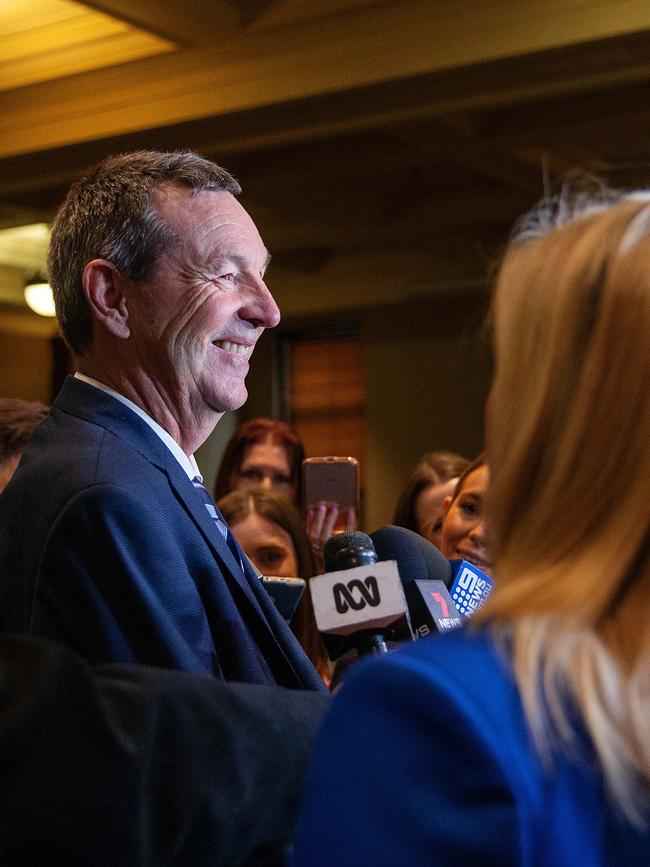

The Mural Hall at Parliament House was full of bigwigs, including then Prime Minister

Malcolm Turnbull, Opposition Leader Bill Shorten and AFL Chief Executive Gillon McLachlan.

I’d probably landed an invitation because I ticked a few boxes: former player for Essendon Football Club and then senior coach of Melbourne Football Club, but more pertinently because the foundation for which I had become an enthusiastic advocate, FightMND, had secured significant federal government backing at our annual Queen’s Birthday weekend fundraiser, the Big Freeze at the MCG.

About halfway through the Prime Minister’s speech, it felt like my body was beginning to shut down.

I was thinking, Geez, I’m in a bit of trouble here.

I made my way towards the back of the room and found a quiet corner where I could have a spell on a couch.

Every now and again someone would edge over to ask for a selfie, and behind every thumbs up I was smiling through gritted teeth.

The AFL’s Head of Government and Stakeholder Relations, Jude Donnelly, wandered over with a look of concern on her face.

‘Are you OK, Neale?’ she asked

‘You’re not looking great.’

My evening was done.

Back in the hotel room, Jan dragged herself out of bed and guided me to the couch.

What a pair we made.

I sat there for a while in a cold sweat, feeling faint, with no sign of improvement, until Jan piped up, ‘This is crazy, we have to get you to hospital.’

When we got to the triage window I was praying that they would not send me over to wait in the rows of vinyl seats. I’m dying here, I kept thinking.

Please don’t put me in the queue behind a sprained ankle.

Fortunately one of the hospital staff came over to Jan and told her that he knew I had MND.

‘Don’t worry, leave it with me,’ he confided, and somehow managed to rush me through to the acute care section.

After being attended by a doctor I sat there next to my trolley, hooked up to the beeping machine, oxygen pumped straight into my nose, wondering if I was going to make it

through the night.

About 1am, Jan reluctantly bowed to exhaustion and caught a taxi back to the hotel.

When she returned the next morning she found me in the same state, in the same chair.

In the end, the hospital managed to find me a bed in their overburdened respiratory ward. Over the next three days I recuperated and on the Thursday morning my doctor broached the subject of being discharged.

‘How will you get back to Melbourne?’ he asked.

When I mentioned that there were seats available on several flights, he expressed his concerns about reduced oxygen in the pressurised atmosphere of an airplane.

‘You’d be better advised driving back,’ he said.

Perhaps reading my look of exasperation at the prospect of an eight-hour drive back home, he relented.

‘I know, I get it. Look, if you can guarantee me that if I give you the all clear you will promise to drive back then we can look at getting you out of here ASAP.’

A couple of hours later Jan arrived to collect me in a hire car. We dropped off the keys at the airport terminal ahead of our flight back to Melbourne.

I told him I’d drive. Well, I did drive … to the airport. I didn’t have time to muck around.

LIFE IS PRECIOUS

I always wanted to make something of my time on this earth, to have my hands on the wheel of life, not just be a car crash waiting to happen. The thing about life is it’s short and precious

and there’s nothing like a terminal illness to reinforce that.

I’ve lived a bloody good life and I’m grateful for all the people who have supported me along the way — those who have given me the faith to believe that tomorrow always has something to offer.

Knowing that my time will run out sooner rather than later, I’ve turned to distilling my philosophy on life, examining my beliefs and attitudes, challenging my own thinking.

I know I might not get to wrap that arm around my grandkids, so I am writing my thoughts down in these pages.

Now, maybe you’ll think I’m full of crap, and I wouldn’t argue with you: all that would tell me is that you believe in something different.

So what do you believe in?

NEALE DANIHER SPECIAL: MY BATTLE WITH THE BEAST

And why? And how much are you prepared to accept that your beliefs and values fundamentally influence the way you live your life?

If so, to what extent?

And, further, that they influence what you do when life throws any manner of circumstances your way?

See, I’ve got you thinking.

Challenge your own beliefs.

Challenge mine.

I know this much.

If you can hold your beliefs and values to the Bunsen burner and they stand up to that heat, then you know you’re backing the right ones.

* Edited extract from WHEN ALL IS SAID & DONE by Neale Daniher, with Warwick Green. Published by Macmillan Australia. Hardcover RRP $44.99. On sale October 24

HOW NEALE LEARNED TO TACKLE MND WITH A POSITIVE ATTITUDE: WHEN ALL IS SAID AND DONE EXTRACT, PART II

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout