Tom Uren, former Whitlam and Hawke minister, dies aged 93

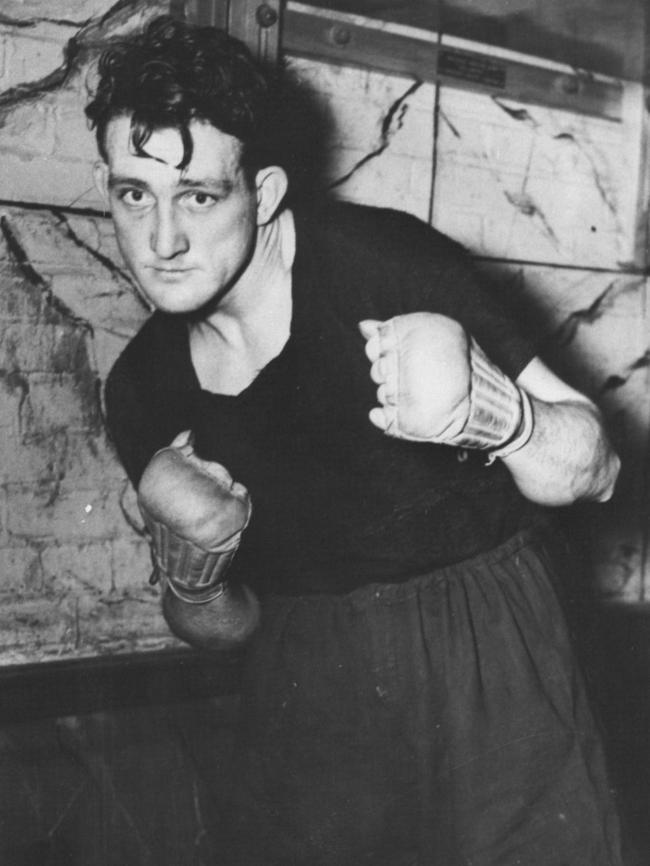

TOM Uren - prisoner of war, champion boxer, and minister in the Whitlam and Hawke governments - died this morning aged 93.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

TOM Uren - prisoner of war, champion boxer, and minister in the Whitlam and Hawke governments - died this morning aged 93.

Mr Uren, who was a prisoner of war on the Burma Thai railway, died at Lulworth House.

Federal Labor MP Anthony Albanese said Mr Uren, whom he considered a father figure, died peacefully.

“Right up until the end he had all his mental faculties, and he was still engaged with people,” Mr Albanese said.

“It takes an extraordinary strength of character to go through what he went through as a prisoner of war and not to have a trace of bitterness about it, but see it as a reason to have faith in humankind.”

Opposition leader Bill Shorten described Uren as a giant of Australia, a giant of Labor.

“With Tom Uren we see a leviathan of the labour movement passing,” Mr Shorten said.

“He comes from that generation of Australians who experienced the Second World War and built a better country afterwards,” Mr Shorten told reporters in Melbourne on Monday.

“I think he will be most remembered as a protector of the working class, as a champion of equality,” he said.

Mr Uren was born on May 28, 1921 in working class Balmain. The family later moved to Manly.

He left school at 13 and joined up when war broke out and spent his 21st birthday in West Timor with the 2/40 Infantry Battalion.

On Australia Day, 2013 Mr Uren, who was awarded a Companion of the Order of Australia in the General Division for his service to veterans, reflected on his time in the POW camp in Omuta, Japan.

There he was able to see the discolouration in the sky from the atomic bomb.

“It was a dramatic ending of the war and left the ongoing challenge to remove nuclear weapons from the planet,” he told the Weekend Australian.

“My POW mates wouldn’t agree with me, and at the time I was glad the bomb had been dropped - we were going home.

“Now, I’m still fighting on those questions, except now it’s a respectable thing.”

Many Labor figures are already remembering Mr Uren.

“RIP Tom Uren. Prisoner of war, champion of peace and warrior for working people. Commiserations to his friend and protege @albomp,” shadow treasurer Chris Bowen tweeted.

RIP Tom Uren. Prisoner of war, champion of peace and warrior for working people. Commiserations to his friend and protege @AlboMP.

— Chris Bowen (@Bowenchris) January 26, 2015

Vale Tom Uren. A fighter for good - right until the end.

— Stephen Jones MP (@StephenJonesMP) January 26, 2015Vale Tom Uren. A huge life, lived for others. An enormous legacy: environment, cities, the power of politics. Thoughts with all who knew him

— Andrew Giles MP (@andrewjgiles) January 26, 2015

RIP Tom Uren patriot & peace activist, soldier & POW, small businessman & environmentalist, agitator & cabinet minister. A great Australian.

— Luke Foley (@Luke_FoleyNSW) January 26, 2015

WAR AND HARDSHIP SHAPED UREN

Tom Uren’s politics of peaceful revolution were moulded by trauma - the depression and years as a Japanese prisoner of war.

During his 31 years as a federal Labor MP of the left, ministries in the Whitlam and Hawke governments and deputy leadership of the party, Uren never abandoned his commitment to socialism and peace.

Though increasingly isolated as Labor became market oriented in the 1980s, he left important legacies - strengthened local government, regional centres and new agencies to protect the environment.

Though physically intimidating, the former professional boxer became increasingly gentle and interested in the arts.

To some he was the conscience of the party, to others a self-indulgent political dinosaur.

His guiding principle was to fight, but not to hate.

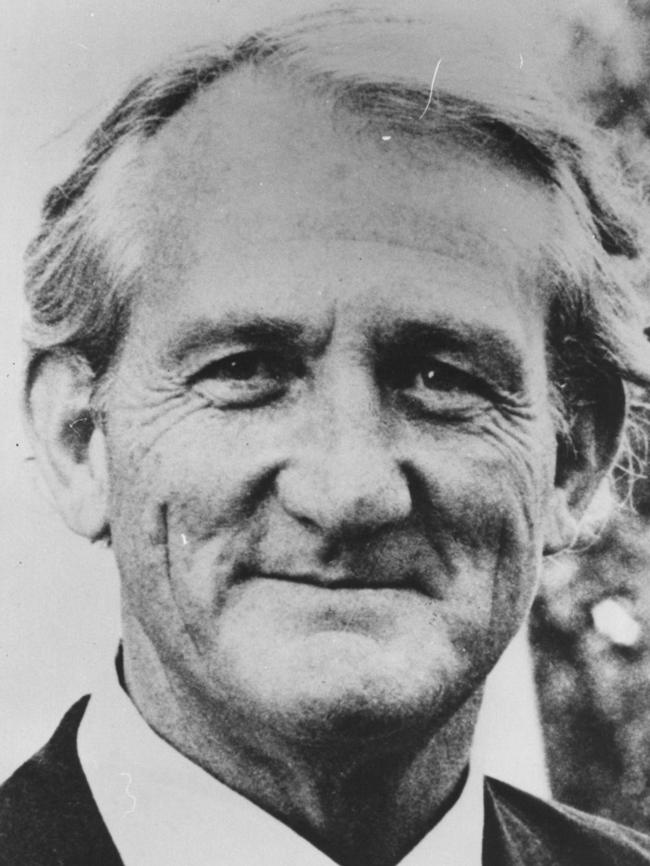

Thomas Uren, who died early on Australia Day aged 93, was born on May 28, 1921 in working class Balmain. The family later moved to Manly.

His father was often unemployed in the depression. His mother pawned household goods to pay the rent and went before a “committee of nice people” which decided if the family deserved welfare. Uren left school at 13 to get what work he could.

A fine sportsman, he played Presidents Cup rugby league, was Freshwater Surf Club’s junior champion and fought for the Australian heavyweight championship.

He joined up when war broke out and spent his 21st birthday on West Timor with the 2/40 Infantry Battalion.

He was taken prisoner after a bloody battle against overwhelming Japanese forces near Koepang. His next three birthdays were as a PoW.

During his 18 months on the Burma-Thailand railway Uren suffered and saw dreadful brutality and debilitating, often fatal, diseases. He stood up to the rifle butts of the guards. Another Australian later said Uren saved his life by confronting a guard who was about to throw him into the river.

Uren learnt a lesson for life.

He was in the Hintok camp under the command of Melbourne surgeon Edward (Weary) Dunlop. Dunlop took the miserable allowance paid to his officers so he could buy food and medicine which were allocated according to need.

English PoWs died more quickly because, hidebound by class division, their officers didn’t share.

Uren later said: “Only a creek separated our two camps, but on one side the law of the jungle prevailed and on the other the principles of socialism.” Eventually, Uren was shipped to Japan and put to work in a factory at Omuta.

When he arrived he would have “exterminated every Japanese person on the face of the earth”.

But at the factory he worked with Japanese and found them considerate and comradely. He shared the only Red Cross parcel he ever received there with his Japanese workmates.

Omuta is about 80 kilometres from Nagasaki where, on August 9 1945, the Americans dropped an atomic bomb.

“The sky was crimson,” Uren wrote. “We didn’t see the mushroom cloud, but we saw the complete discolouration of the sky.” With the war over, Uren was one of the prisoners selected to administer Omuta. He tried to democratise the place overnight by decreeing that women no longer had to bow to soldiers.

Uren finally came home and in 1947 married Patricia Palmer. They had two adopted children.

He tried to revive his boxing career after working his way to London as a stoker, but the years of privation and disease had taken an irreparable toll.

“The other fighters never beat me; malaria beat me,” he said. Back again in Australia, he became a Woolworths storeman, after missing a trainee manager’s position because of his lack of education. Within 21 months he was managing the Lithgow store. He joined the Labor Party after attending Ben Chifley’s funeral in nearby Bathurst in 1951.

In 1958 he entered federal parliament after winning a tough preselection battle for the safe western Sydney seat of Reid. As a member of the left, he became very close to the Melbourne idealist Jim Cairns, one of the few men he loved. Though he felt Cairns later made terrible mistakes, they remained lifelong mates. In those days, with the DLP powerful and fear of communism rampant, Uren’s outspokenness on issues like the US North West Cape communications base attracted hostile attention.

He said he was non-communist, but not anti-communist. He had card-carrying friends.

Uren won an epic defamation case against Frank Packer’s Consolidated Press for articles accusing him of asking parliamentary questions supplied by Soviet diplomat Ivan Skripov, who was later expelled for spying. He also won an action against Fairfax.

With the money he built “Fairfax Retreat” and “Packer Lodge”. Uren was an early and uncompromising opponent of the Vietnam war.

In 1970 he privately prosecuted a constable he said constantly pushed him during an anti-war rally in Sydney.

After losing the case and being ordered to pay $80 costs, he opted for 40 days hard labour instead.

He ended up doing only two days before someone, to Uren’s disgust, paid the money.

He saw the inside of police cells again when arrested for demonstrating in Brisbane against Queensland Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s ban on street marches.

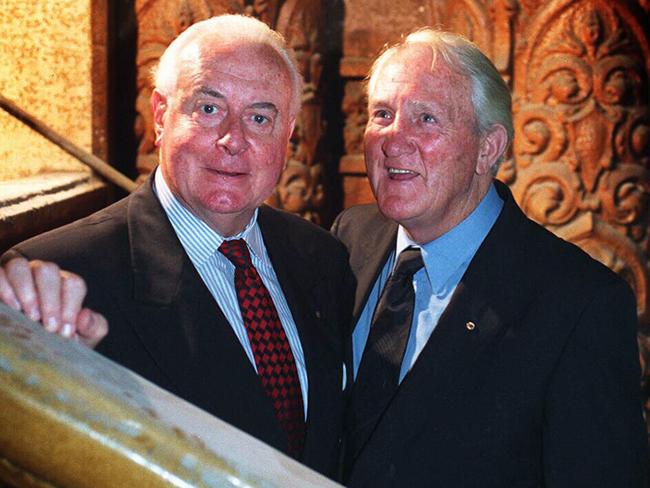

After the 1969 election, in which Gough Whitlam took Labor close to government, Uren became urban and regional affairs spokesman. He kept the portfolio after Whitlam came to power in 1972 and made his new department a powerhouse of ideas. Uren proved an able administrator as well as a driving force for change.

Although some of his proposed regional growth centres were stillborn, a few - like Albury-Wodonga - took off.

Sewerage was brought to many parts of outer Sydney and Melbourne and historic inner city precincts were saved from ugly development. Uren thought his greatest achievement was the creation of the Australian Heritage Commission; his greatest disappointment failing to stop the flooding of Lake Pedder in Tasmania.

Two relationships deeply troubled Uren during this period.

In 1974, Patricia left him.

“She was very hurt and felt I didn’t really need her any more,” he later wrote. “It was a tremendously sad period of my life and I should have fought harder to hold her.” When Patricia developed breast cancer, she returned. They were together the night before she died in 1981.

The other was Cairns’ relationship with Junie Morosi.

Uren knew she would be trouble and tried to talk his friend out of hiring her.

But the new treasurer was intensely in love and pleaded that unless he put Morosi on staff he’d never have the time to see her. Uren, putting his heart before his head, finally gave her appointment his qualified blessing and made his Canberra flat available to the pair.

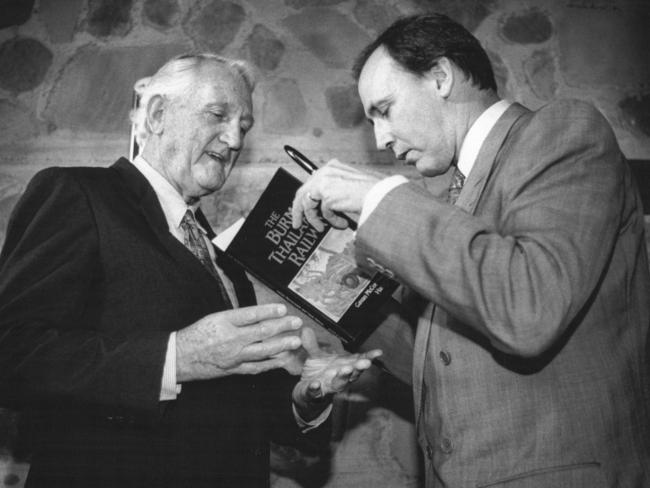

After the dismissal and Malcolm Fraser’s landslide victory, Uren was elected deputy leader - winning the final ballot against Paul Keating by 33 votes to 30.

It was a difficult time. Whitlam had lost his spark, but not his habit of acting without consultation. Uren felt excluded.

After the 1977 election, when Bill Hayden took over from Whitlam, Uren lost his position as deputy to Lionel Bowen.

Uren was ambivalent about Hayden and the pair fell out over uranium exports.

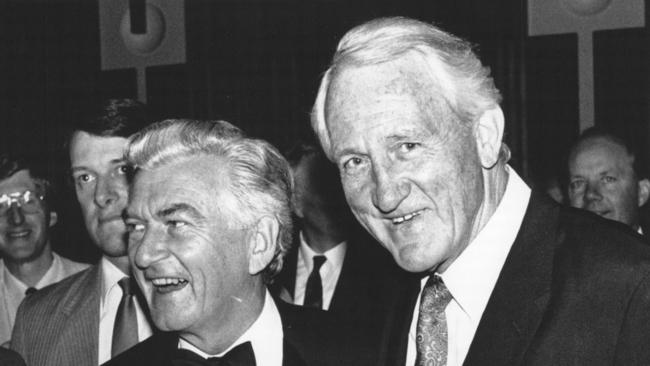

Although Hayden made big inroads into Malcolm Fraser’s majority in 1980, Uren came to believe Bob Hawke was the better bet.

Uren overreached himself in 1982 when he tried unsuccessfully to swing the Left behind Hawke’s first challenge. But eight months later the Left shifted and Hawke took over in time to lead Labor back to power.

Hawke, to Uren’s disappointment, made him territories and local government minister. He had a furious row with the new PM and when Hawke ended the meeting with an offer to shake hands, he was told to “shove it up your arse”.

Yet Uren threw himself into local government for the two terms he held the portfolio, fighting for more money for the third tier of government.

He was particularly proud of a 1986 financial assistance act that gave local government more equitable and predictable funding and special programs to improve recreational and social facilities. An alternative view came from acerbic Finance Minister Peter Walsh: “Uren diligently set about using his minor portfolios to rebuild his old Urban and Regional Development empire, in which many of the Whitlam government’s most financially disastrous monument-building experiments in social engineering had been incubated.” Uren became distressed by the government’s faith in the market. The period was “bloody awful, lacking real compassion.” He didn’t stand for the ministry after the 1987 election and had a final term on the backbench before retiring in 1990.

But he never went away.

He continued to criticise the Labor government and, when it fell, the coalition. He fought for a better deal for old PoWs. With former Australian Democrats leader, the late Janine Haines, he went to Baghdad to help free 29 Australians being held hostage in the lead-up to the first Gulf war.

In 1991 he married Christine Logan, an Australian Opera singer, gaining a little daughter in the process.

He mellowed towards Whitlam, though less so with Hawke.

He found new joys, particularly in art. Lloyd Rees was another he loved.

He talked a lot about love. A guiding star was the Brazilian socialist philosopher Paolo Freire, who wrote: “No matter where the oppressed are found, the act of love is commitment to their cause.”