True story of a village vs neo-Nazis that inspired play The God Of Isaac

When Neo-Nazis tried to hold a march through the predominantly Jewish community of Skokie, the normally quiet village made the news around the world

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Skokie is a quiet residential suburb in Illinois, less than an hour’s drive north of the main city centre of Chicago in the US. Home to about 70,000 mostly middle-class people, and calling itself the “world’s largest village” for its harmonious sense of community, it was not usually the sort of place that drew the attention of the entire nation, much less further afield. But in 1977 that’s just what happened when the village became a constitutional battleground making global headlines.

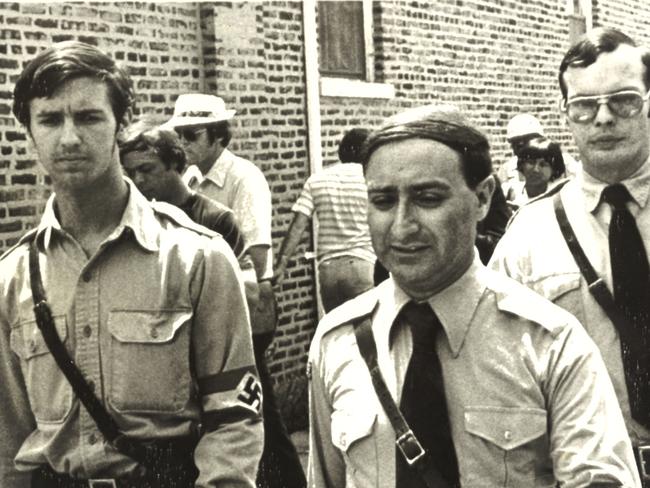

It all began with Frank Collin, head of a local neo-Nazi group the National Socialist Party of America (NSPA), signalling his intention to lead a march through Skokie. Although Skokie was only one of a number of places he planned to march, it was seen as particularly provocative, given that 40,000 of Skokie’s residents were Jewish and about 5000 were survivors of the Holocaust.

Collin had been battling legal action for his marches elsewhere but this time he came up against his toughest resistance, primarily from a tight-knit core of Skokie’s citizens. It would become a battle that would have people debating the American Constitution. It also made young playwright James Sherman, who grew up in Skokie, question what it was to be Jewish. It became one of the inspirations for his 1980s play The God Of Isaac, a new production of which opens this week at the Eternity Playhouse, Darlinghurst (previews from September 5).

When residents of Skokie found out about the planned Nazi march, they were outraged. They were incensed that their peaceful community would play host to something so obviously designed to disrupt that peace. Hearing these concerns at a public meeting Mayor Albert J. Smith told the council’s lawyer Harvey Schwart to get a court order to prevent the march on the grounds that it was a deliberate attempt to “incite or promote hatred against persons of Jewish faith or ancestry”.

Collin was used to fighting legal battles to be allowed to march. Despite the US having been to war to defeat Nazism, Collin wanted to be free to spout his Nazi-inspired white supremacist messages and display the symbols of Hitler’s regime. The son of a German immigrant, he had been a member of George Rockwell’s National Socialist White People’s Party in the 1960s. After Rockwell was assassinated in 1967, Collin had a falling out with the man who replaced Rockwell, particularly after his father came out and claimed to have been a Holocaust survivor and that Collin had Jewish ancestry.

Collin denied it and formed his own party, with himself as leader. He held rallies at Marquette Park, but after Nazi party members had a run-in with African-Americans gathered in the park, the city of Chicago had insisted on a public safety insurance bond of $350,000 for any future rallies.

He took legal action against the City of Chicago for violating his First Amendment Rights — the right to free speech. But while his case was caught up in the courts, he decided he would test the waters by holding marches in various places around Chicago. He shouldn’t have been surprised to meet resistance from Skokie.

The American Civil Liberties Union came to the aid of Collin and the NSPA, challenging the injunction on the grounds that it violated First Amendment Rights. But the court of Illinois decided the Nazi swastika was not protected by the First Amendment, allowing the marchers to march but without displaying swastikas.

While the Illinois Supreme Court overturned that ruling, the continuing legal problems, the national backlash against the Nazis and even dissent within the NSPA, resulted in the march being moved to the Federal Center Plaza in Chicago.

When Collin finally led his marchers out, on June 24, 1978, he was met by a sea of anti-Nazi protesters. An egg hurled at the Nazi leader was deftly intercepted, but ultimately Collin called it quits after just 10 minutes of trying to speak above the roar of the crowd. Collin was later expelled from the party and served prison time for child sex offences.

Skokie rightly took a great deal of pride in their victory. A film crew visited the village in December 1980 to recreate elements of the drama of the incident for the film Skokie, starring Danny Kaye, Eli Wallach, Carl Reiner and Kim Hunter. It was released in 1981, the same year the town opened a Holocaust Museum and Education Center.