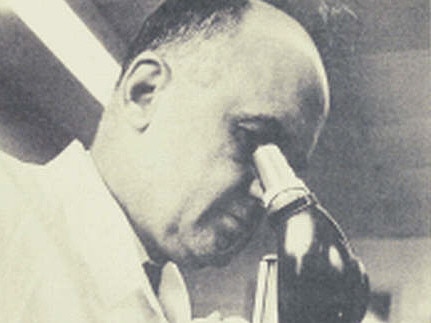

Maurice Hilleman, unsung hero of vaccination, saved millions of lives in flu pandemic

When Dr Maurice Hilleman read about a flu outbreak in Hong Kong in 1957 he sounded the alarm about a coming pandemic

Early in 1957 Hong Kong was in the grip of an influenza outbreak. It might have seemed unremarkable to many but not American doctor Maurice Hilleman who was working at the US Army Medical Center when he read an article in the New York Times reporting 20,000 people were lined up at dispensaries in the Asian city.

The story got him thinking that this could be a serious pandemic, like the 1919 Spanish flu that had killed millions around the world. The world seemed overdue for one. Hilleman sent away for a specimen of the disease, rounding one up from a US serviceman stationed in Hong Kong. His analysis determined this was a disease to which few Americans carried immunity.

Hilleman announced that a pandemic would start “when school began in the fall” and his prediction proved to be extremely accurate. But, fortunately, his warning came early in the year. After making his announcement he went to the manufacturers of vaccines and urged them to begin producing massive batches to counter the coming outbreak.

Hilleman is credited with saving thousands of lives. While the death toll was still about 68,000, that was vastly less than the estimated 1-4 million that could have died, had it not been for Hilleman’s alert.

Hilleman, who was born a century ago today, was never a big self-promoter. Although he developed more than 40 vaccines, for common diseases such as mumps, measles, hepatitis (A and B) and rubella, he was never a household name, like Jonas Salk or Louis Pasteur, despite having helped eliminate many childhood diseases and saving millions of lives.

He was born on August 30, 1919 on the family farm near the town of Miles City, Montana in the US. His twin sister died within hours of the birth and his mother died a few days after. As a child he worked on the family farm and would later credit his work with chickens for his ability to grow cultures to create vaccines, which was then often done using hens’ eggs.

Working on the farm also gave him a curiosity about nature and science. One of his favourite books when he was young was The Origin Of Species by Charles Darwin. Although his father was a strict Lutheran who dragged his children to church every Sunday, Hilleman became sceptical, preferring the logic of science to sermons. He is said to have even once asked a priest to prove wine could turn into Christ’s blood.

With financial support from his brother, who could see the value of Hilleman’s studies, he gained a scholarship to Montana State University and went on in 1944 to gain a doctorate in microbiology at the University of Chicago. His professors urged him to become an academic, but Hilleman was determined to work in industry, where he felt he would be able to develop vaccines.

He joined the virus laboratory of pharmaceutical manufacturer E.R. Squibb & Sons, where he developed a Japanese B encephalitis vaccine, saving lives of American military serving in the Pacific.

In 1948 he moved to the US Army Medical Center (later Walter Reed Army Institute of Research) where he made discoveries relating to the way a virus changes when it mutates. It was this work that helped him understand the dangers of the 1957 pandemic and to alert authorities.

Joining the pharmaceutical company Merck & Co in 1957, he

was there when, in 1963 his daughter Jeryl Lynn came down with mumps. He took a swab from her throat and developed a mumps vaccine.

Among the first to receive the vaccine was his other daughter Kirsten.

Hilleman rose to the position of senior vice-president of Merck’s research labs, retiring in 1984 at the age of 65. But always energetic, Hilleman then continued on as head of Merck’s Institute of Vaccinology.

With a reputation as one of the world’s best immunologists, many were surprised that he never received the Nobel Prize for any of his many achievements. But his advice was sought by many, serving as adviser to the US National Institute of Health’s research program into AIDS and was also as an adviser to the World Health Organisation.

His reputation was unfairly assaulted by the now discredited report published in 1998 linking his MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine to autism. Hilleman even received death threats. The paper was later retracted.

In March 2005 Merck combined with the University of Pennsylvania to create the Maurice R. Hilleman Chair in Vaccinology in his honour. He died in April 2005.