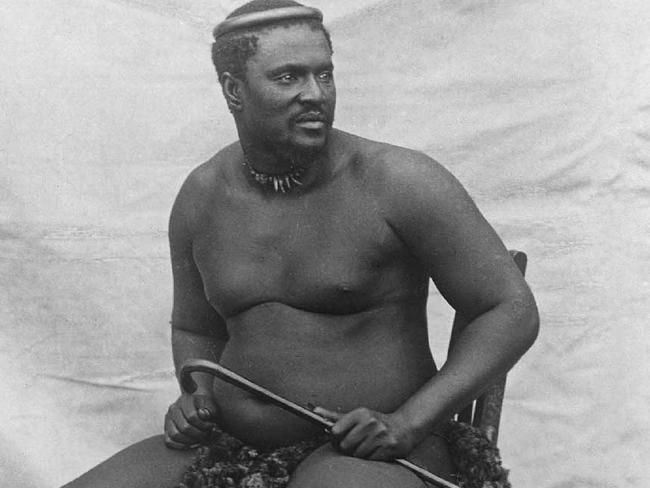

Last Zulu king Cetshwayo a symbol of warrior peoples’ defiance

As long as King Cetshwayo remained at large there was still a chance of resistance from the Zulu nation but the British finally got their man 140 years ago today

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Real-life crime of passion inspired Chicago the musical

- Fuel crisis inspired Mini classic with a big heart

General Sir Garnet Wolseley, commander of British troops fighting the Zulus, was concerned. The Zulu armies had been defeated at the battle of Ulundi in July 1879, but their leader, King Cetshwayo kaMpande, was still on the run.

Although many of the chiefs loyal to him had surrendered, there were still doubts that peace could be secured as long as Cetshwayo remained at large. Wolseley set up camp at Ulundi and sent out patrols in search of the king. There were rumours he had headed to the Ngome forest, about 50km north of Ulundi.

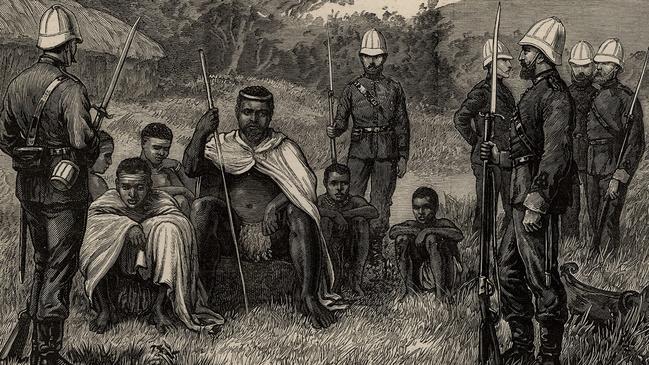

On August 28, 1879, a patrol of dragoons under the command of Captain Lord Edric Gifford came to the crest of a hill overlooking the kwaDwasa umuzi, the home of local chieftain Mkhosana, who was harbouring the fugitive king. Gifford recognised the imposing figure of Cetshwayo and, under cover of night, with help from troops under Major Richard Marter, they raided the compound.

The king surrendered and was later taken to meet Wolseley, who told him he had been deposed. Cetshwayo presented the general with a necklace made of lions’ claws. Wolseley later had the necklace broken up and each claw inscribed with “Cetewayo [sic], 28th August 1879”, before giving them away to female friends.

It was the end of the reign of the last king of the Zulus and marked the end of the proud warrior people’s resistance to British rule.

Cetshwayo was born in 1826, the son of Mpande, half-brother of King Shaka. When Mpande’s brother Dingane assassinated Shaka and took power, Mpande served alongside him but after Dingane was defeated while trying to take on the invading Boers in 1838, ceding territory to the Boers, Mpande began to turn against his brother. In 1840, Mpande led an army against Dingane, in which Cetshwayo also fought, defeating and killing Dingane. Mpande reluctantly became king. When he favoured a younger son, Mbuyazi, as his heir rather than Cetshwayo, tensions between the sons erupted into civil war. In 1856 Cetshwayo killed off his rival at the Battle of Ndondakusuka.

When Mpande died in 1872 Cetshwayo took control, and was confirmed as king in 1873. Establishing the capital of Zululand at Ulundi, Cetshwayo began rebuilding Zulu prestige. One of his priorities was to reclaim some of the territory taken from him by the Boers, so he began a program of building up his army, but also looked to the British to try to resolve the dispute with South Africa after the British annexed it in 1877. But Sir Bartle Frere, Britain’s High Commissioner for South Africa, had plans to also annex the Zulu kingdom.

Frere began a concerted campaign to depict Cetshwayo as a military despot with designs on Britain’s new territory of South Africa.

Cetshwayo made a show of co-operation, withdrawing his troops from the border but, in December 1878, Frere issued an ultimatum for the king to dismantle his military and disarm his troops.

In January 1879 the British invaded Zululand, without the approval of the British government.

Confident they would easily defeat Cetshwayo and his army, the British, under Lord Chelmsford, suffered shocking losses at Isandhlwana and Rorke’s Drift. But the British soon regained momentum and in July, Chelmsford, desperate to defeat the Zulus before his replacement Wolseley arrived, fought the Zulus at Ulundi.

Cetshwayo tried to negotiate with the British but Chelmsford rejected peace offerings and pressed on with the battle, winning a decisive victory but allowing Cetshwayo to slip away.

It was left to Wolseley to accept the surrender of the Zulu chiefs and to track down Cetshwayo. The deposed king remained a prisoner in South Africa until, in 1882, he was given permission to travel to England. There he was feted by the press and met with Queen Victoria, who presented him with a silver mug. While in England, Cetshwayo rallied support among politicians for his restoration.

When the British reinstalled him in 1883, it was as king of a partitioned country. But he was soon ousted by a rival Zulu chief. He was forced to flee to the British Zulu Native Reserve at Eshowe where he died of a heart attack in February 1884.