Australia’s first millionaire James Tyson was the son of a convict

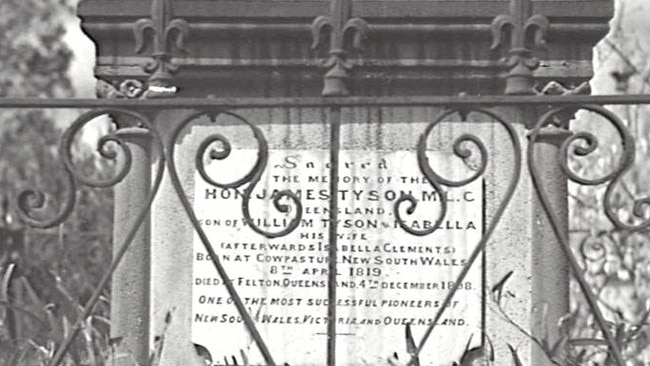

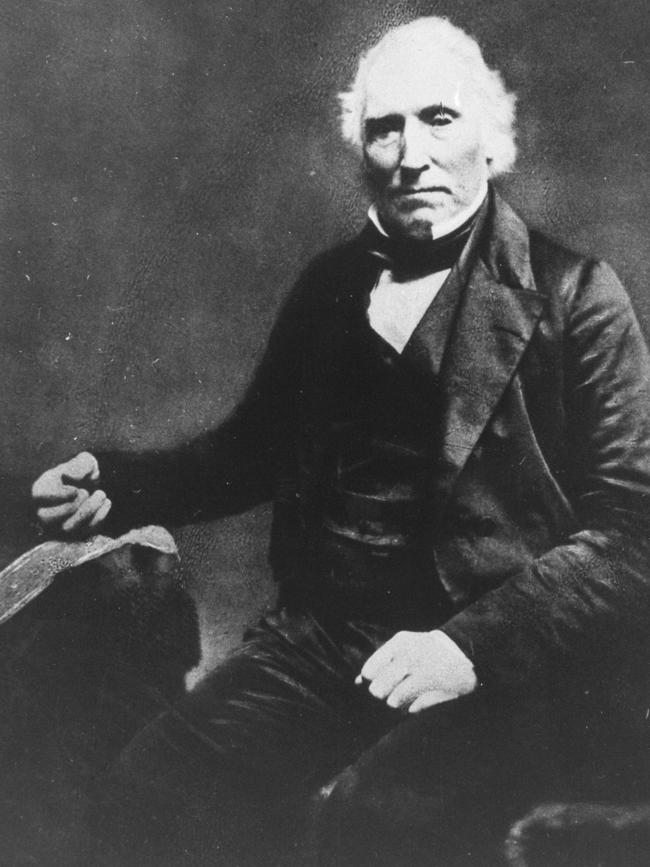

Australia’s first millionaire was born at Cowpastures, now Narellan and Camden, in 1819, the son of a farmer and a convict. James Tyson saw the benefit in working over playing and living a frugal lifestyle despite his growing wealth. MORE: ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

He didn’t have a mansion, often chose to sleep outdoors while travelling and avoided wearing fine garments.

But when he died in 1898, James Tyson left an estate worth £2.36 million, which at the time was the biggest estate in the country.

Australia’s first millionaire was born at Cowpastures, now Narellan and Camden, in 1819, the son of a farmer and a convict.

But from an early age Tyson was ambitious; he saw the benefit in working over playing, in accumulating money over spending it and in living a frugal lifestyle despite his growing wealth.

Author and local studies librarian for Campbelltown City Council, Andrew Allen, says Tyson did not fit the image of a self-made man.

“There’s a story that is told about Tyson when he was young in which his mother gave him a flute as a birthday present, which he soon sold,” Allen says.

“When his mother asked him why he sold it, he replied ‘I needed the money to buy a heifer because heifers can breed and flutes can’t’.

“He clearly showed signs from early on that he was motivated to make money.”

Tyson’s first serious foray into the business world came when he and his older brother William established a butchery in goldfields country near Bendigo in 1852. Three years later, they were able to sell that business for about £80,000.

GET MORE CONNECTED:

What you get as a subscriber to The Daily Telegraph

Download our app and stay up to date anywhere, anytime

From there, Tyson invested in a series of grazing stations, establishing himself as a pastoralist.

By the time of his death, he had more than 2.1 million hectares of land stretching from North Queensland to Gippsland in Victoria.

His gravestone states he was “one of the most successful pioneers of New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland”.

That he was a successful man was not in question, even during his own lifetime. But there were many stories about Tyson that highlighted his eccentricities and presented a contradictory view of him.

When visiting properties he invested in, he was known to sleep outdoors with the swagmen rather than in the more comfortable confines of the manager’s home and he is said to have once swam across a river rather than pay the toll for crossing the bridge.

When asked how he would feel about his money being spent frivolously by his descendants after his death, Tyson is said to have responded: “If they have as much pleasure spending it as I did in getting it then that money won’t be wasted.”

“He had a couple of nicknames,” Allen says.

“He was sometimes referred to as ‘Daylight Jimmy’ because of his habit of going to bed early and rising early, only ever being awake during daylight hours. He was also sometimes known as ‘Hungry Tyson’ or ‘Mean Tyson’ which I think was an unfair nickname because he had moments of great charity throughout his life.

“I think it would be fair to say he was greatly misunderstood.”

Allen says he was described by some as being shy or awkward, particularly around women, which may have given rise to the rumour he disliked women.

However, he would go on to donate to the building fund for the Women’s College at Sydney University.

Bush poet Banjo Paterson even dedicated a piece to him calling it T.Y.S.O.N in which he highlighted this contradiction.

“I never care to make a splash; I’m simple but I’ve got the cash” and then “There’s many a thing he used to do; good-hearted things that no one knew”.

He died in 1898 of what was described as an inflammation of the lungs, alone at his home in Felton on the Darling Downs of Queensland.

He never married, he had no children and left no will. His money went to his relatives who remained in the Campbelltown area and while he was initially buried at Toowoomba in Queensland, his body was moved and reinterred three years later in a family tomb at St Peter’s Cemetery, Campbelltown.

FIRST FLEET COWS MADE IT TO CAMDEN

It was recorded that a group of five cows, a bull and a calf escaped their confines after landing in Sydney with the First Fleet in 1788.

The cows were spotted several times over the years, an image even recorded in a cave wall at Kentlyn by a local Indigenous tribe, and after seven years were found near present day Camden.

The area was named Cowpastures Plains after the escaped herd. They were protected by government order until 1804 when the herd is said to have numbered up to 3000.

FIRST OF THE MILLIONAIRES’ CLUB

Online wealth calculators report the value of Tyson’s estate on his death in 1898 would be the equivalent of around $320 million today.

While Tyson was Australia’s first, there are many more millionaires in the country today — more than 1.18 million millionaires were recorded in Australia in 2019, according to Credit Suisse’s Global Wealth Report.

By comparison, 40 per cent of the world’s millionaires live in the US where there are more than 18.6 million millionaires.

CHILDREN’S PARK THE FINAL RESTING PLACE FOR 5000 SOULS

Children run and play here, mothers push prams and dogs chase frisbees. It’s a typical suburban scene.

But there’s nothing typical about St Thomas Rest Park at Crows Nest.

Until the 1960s the park was a cemetery with about 5000 souls buried beneath its surface, the first laid to rest in 1845 making it the first European burial ground on the northern side of Sydney Harbour.

But as it later sat abandoned, an act of Parliament made it possible in 1967 for the cemetery to be used by North Sydney Council as open parklands.

A collection of headstones were moved into one area of the park, allowing the rest of the 1.6ha (four-acre) lot to be given over to green space, a luxury in an increasingly-crowded suburban area.

Last week, signs were placed at the park to celebrate the site’s prominent history. Despite this, few of the families who use the space today know the history of what lies below their feet.

“It’s certainly unusual in that it’s a very interesting attempt to balance the public space needs of a growing suburb with history,” North Sydney Council historian Ian Hoskins says.

“Under the lawn at St Thomas’s Park there are about 4000 to 5000 bodies but today it’s a very popular family spot, particularly after school.”

The fact it was once a busy burial spot is not hidden by North Sydney Council, in fact, near the entrance on West St, where the original wrought iron gates and pillars stand, you will find a sign that reads in part “Please respect this place as a burial ground … people are still interred here.”

The cemetery was created in 1845 when prominent landowner and politician Alexander Berry was looking for a place to bury his beloved wife, Elizabeth.

With no options north of the Harbour where he owned more than 500 acres (202ha) of land (covering much of what is today Wollstonecraft, Waverton and Crows Nest) Berry donated a portion of four acres for burial space connected to St Thomas Anglican Church about one kilometre away.

There, amongst the high blue gums and turpentine trees, he built a stone pyramid underneath which he buried his wife in a crypt. He was also buried under the pyramid, which Hoskins says could be the only pyramid mausoleum in Australia, in 1873, having left an inscription at the base which read “entrance to the vault four feet below here” for the undertakers.

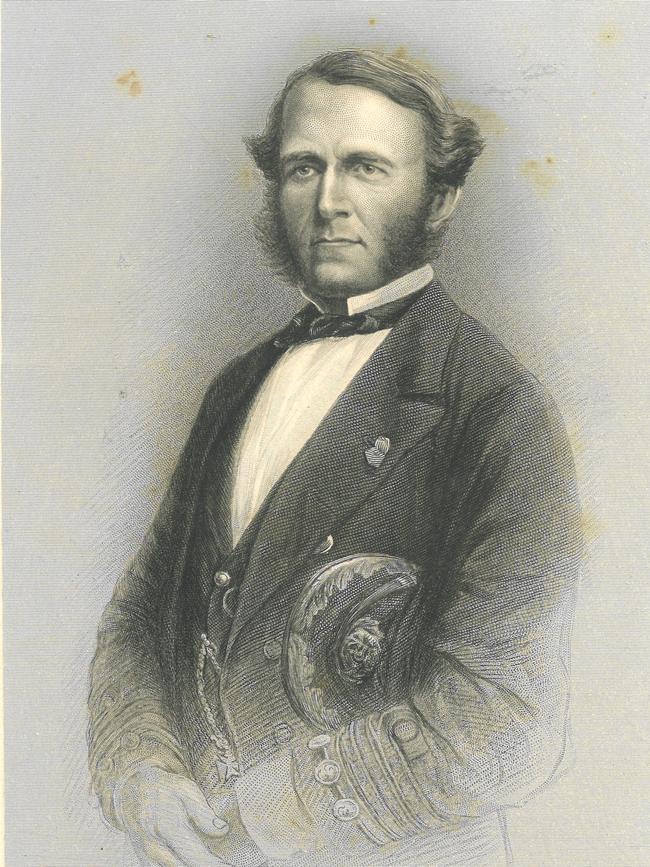

The first rector of the new St Thomas Church was Reverend William Branwhite Clarke, who was one of Australia’s finest pioneering geologists.

He was very well connected to the science world and established a connection with Royal Navy captain Owen Stanley, a Victorian hero who took the HMS Rattlesnake up the coast to Papua New Guinea and on his return, died of a tropical disease while still on board in Sydney Harbour in 1850.

Reverend Clarke officiated at his funeral at St Thomas’s and he was buried there with full naval honours.

“My theory is that from that moment St Thomas’s becomes the unofficial naval and maritime cemetery for Sydney,” Hoskins says.

“After Owen Stanley, up to two dozen sailors and naval officers were buried there.”

In 1875, Commodore James Goodenough, who was in charge of the portion of the Royal Navy fleet permanently established in Sydney Harbour at the time, was killed in the Solomon Islands when a poisoned arrow hit him in the neck.

Despite the fact Rookwood Cemetery was already operating in Sydney, he was buried at St Thomas’s, cementing its maritime connection.

Hoskins says the last burial took place there in the 1950s, after which the cemetery fell into a state of disrepair due to a lack of money and interest and by the 1960s the headstones were being reclaimed by nature.

“It’s a lovely cultural landscape,” says Hoskins, who manages the remaining headstones.

“It’s fortunate that decisions were made to retain a precious piece of green space in a highly settled area and that our Colonial history can live side-by-side with a well loved and used park.”

NEW LIFE FOR OUR OLD BONES

While St Thomas Rest Park is rare in that it’s a burial site turned into parkland, it is not unique. Camperdown Cemetery in Newtown was created in 1848 and for a while was the main general cemetery in Sydney with 18,000 people buried there.

But an act of Parliament in 1948 turned the site over to the local council which removed the headstones and turned it into a park bordering St Stephen’s Cemetery. Nearby, Balmain Cemetery, which was created in 1868, was turned into a park after it closed in 1912.

More than 10,000 people were buried in what is today known as Pioneer Memorial Park in Leichhardt.

FOREVER IN LOVE WITH ELIZABETH

A native of Edinburgh, Alexander Berry came to Sydney in 1808, a ship’s surgeon-turned merchant.

While sailing near Cadiz off the coast of Spain, Berry met Edward Wollstonecraft and the two went into partnership back in Sydney. They acquired land near Shoalhaven, thus the town of Berry, as well as north of Sydney Harbour.

In 1827 Berry married Wollstonecraft’s sister, Elizabeth. The couple were building Crows Nest House when Elizabeth died in 1845, leaving no children.

The pyramid mausoleum he built for his wife was a sign of his devotion, and Berry went on to live out his years as a recluse in his grand estate. He died in 1873.

TB SUFFERERS FORCED TO DIE ALONE IN ISOLATION

The gates to the Waterfall General Cemetery are permanently closed these days, the graves and headstones of the people buried there almost entirely lost to the bush.

But their stories are eerily similar to many we have heard in recent months stemming from the insidious creep of COVID-19 which forces patients into isolation way from their families, and in the saddest cases to die alone.

Located northwest of Helensburgh in Sydney’s south, the cemetery is the final resting place of more than 2000 people, almost all of whom died of tuberculosis in the first half of the 20th century.

Tuberculosis, or consumption as it was also known, was one of the leading causes of death in the early to mid-20th century, sometimes taking whole families.

One of the most poignant stories is that of Eunice Sloane, who was buried at the cemetery in 1918, the same month as her 10-year-old daughter. A month later her six-year-old son would join them, the youngest tuberculosis casualty buried there.

The airborne bacterial disease was considered highly infectious and, as such, sufferers were isolated away from their families and the community.

While today it is treated with antibiotics, there was no known treatment for tuberculosis prior to World War II but it was believed that fresh, clean mountain or sea air along with a good diet and plenty of rest could aid recovery.

However, the statistics for 1935 show the survival rate was not great; 939 deaths resulted from 1572 cases recorded in NSW.

It’s not difficult to trace similarities between COVID-19 and tuberculosis, says historian and author Caroline Hardie.

Back then, the government tried to control the spread by making it mandatory for doctors to report known cases, much in the same way contact tracing helps us control COVID-19 today. And isolation was the best way to prevent the spread, as it is today with coronavirus.

“Many sufferers were forced to die alone due to the isolation, another grim similarity to the stories we hear of COVID-19 sufferers dying alone in aged-care facilities today,” Hardie says.

“Imagine a little six-year-old diagnosed with tuberculosis and forced to die in isolation.”

There were two main facilities that cared for tuberculosis sufferers in the early 20th century: Bodington at Wentworth Falls in the Blue Mountains and the Hospital for Consumptives at Waterfall, to which the Waterfall General Cemetery was attached.

While he can no longer visit the gravesite of his father, Charles Whalan, at the cemetery, 91-year-old Ronald Whalan will never forget the kind and gentle man he lost to the disease when he was just nine years old.

The young family had already suffered the loss of Ron’s mother, Irene Egan, to another disease — meningitis — when she was 19 on New Year’s Day 1932.

When Charles was diagnosed with tuberculosis, he was admitted first to Bodington and then the Hospital for Consumptives. The care of young Ron and his sister was shared among Charles’s family in Oberon in the wider Blue Mountains.

But Ron recalls one visit from his father, who must have been deemed well enough to travel to visit his family, says Hardie, who is also a distant cousin of Ron’s.

“We had a little game of cricket: Dad would bowl and I would bat and then we’d swap,” he recalls of the last time he saw his father.

“I loved my dad, he was a lovely dad-type, a kind and gentle soul.”

Charles died at the Hospital for Consumptives in July 1939 and was buried in the adjoining cemetery.

He must have suffered the same condemnation from the local community as was documented in the papers of the day.

Locals, afraid and concerned about the infectious nature of tuberculosis, appealed for the hospital to contain patients within the grounds. Some patients would sneak out to visit local hotels, it was reported, which was strictly forbidden by medical staff.

Yet one doctor appealed to the community in a news article in 1909 when the hospital opened:

“The poor unfortunates haven’t committed any crime,” Dr Payten said.

“They have contracted consumption and the institution is a hospital and not a prison.”

The last burial at the cemetery was in 1949 and the hospital closed in 1958.

SON’S 90-YEAR WAIT TO VISIT GRAVE

Although he was only two years old when she passed, Ron Whalan will never forget his mother, Irene Whalan (Egan), who died of meningitis in 1932.

She was just 19 years old when she complained of a headache on Christmas Day 1931. She was gone by New Year’s Day and buried at Merriwa in the Upper Hunter.

Ron has never been able to locate her grave.

But now, with the help of a local woman who says she knows where his mother is buried, Ron plans to visit the site later this year with a cross he has made.

It reads: “You were 19, I am 91 and I’ve missed you all my life.”

DEADLY TB STILL IN OUR MIDST

While the rate of tuberculosis infection in Australia is one of the lowest in the world, it remains the deadliest infectious disease worldwide. World TB Day is held on March 24 each year, a date chosen to coincide with the announcement by doctor Robert Koch in 1882 that he had found the bacterium that caused tuberculosis, an important first step in finding a cure.

While TB is preventable today through vaccination, and curable, 4500 people die from the

disease worldwide each year. In Australia, 1440 new cases were diagnosed in 2018, according to NSW Health.

Gold rush’s forgotten man finally makes his mark

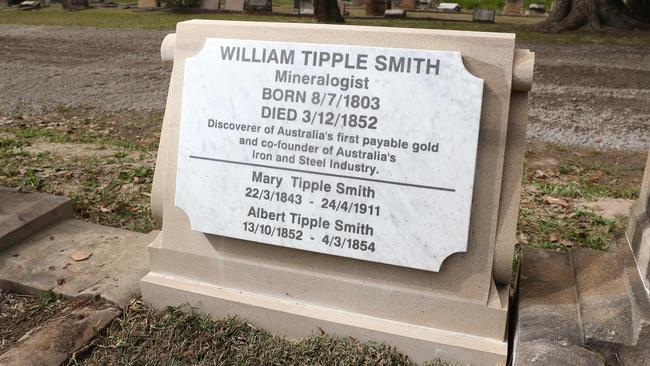

Bill Hamburger has spent his life telling anyone who will listen that his great-great-grandfather, William Tipple Smith, was the first to find payable gold in Australia. But with the history books incorrectly claiming it was Edward Hargraves, he was fighting a losing battle.

Until this week.

With the unveiling of an imposing marble headstone on Smith’s previously unmarked grave at Rookwood Cemetery, he has been announced as the discoverer.

It has been a decades-long battle for 91-year-old Hamburger to change the course of history, greatly aided by his relative and historian Lynette Silver who discovered a cache of missing letters in the 1980s that proved it was Smith in 1848, not Hargraves in 1851, who found gold at Yorkey’s Corner, today called Ophir, near Orange.

“I feel 169 years of injustice has been fixed up,” Hamburger said of the unveiling of the headstone.

“He was branded a fraud and that continued because nobody knew any different, except the family of course.”

In the 1980s, Silver, the great-great-great niece of Smith, was researching her family tree when a distant relative gave her some typed copies of old letters written by Smith, and she began a search for the originals, which she discovered, misfiled by the Colonial Office in London.

GET MORE CONNECTED:

What you get as a subscriber to The Daily Telegraph

Download our app and stay up to date anywhere, anytime

They told how Smith had found gold on the western slopes of the Blue Mountains in 1847 and attempted to make the find official by sending samples to eminent geologist Roderick Murchison in London with the hopes he would pass the find on to the Colonial Office in London, which he did. But the Crown was not interested.

Regardless, Smith set out again in 1848 to search for gold and found 3.5 ounces at Yorkey’s Corner. He took the sample to Governor Charles Fitzroy in Sydney offering to reveal the location for £500 pounds, to cover the costs of his expedition.

He heard nothing back. Then, in 1851 Hargraves was lauded as the first man to find payable gold in Australia. We can only imagine Smith’s frustration.

The story goes that Hargraves went into partnership with two men – James Tom and John Lister – who started prospecting near Bathurst but found nothing.

Hargraves left for home leaving Lister and William Tom, who replaced his brother James, to continue the search.

Acting on information from the uncle of the Tom brothers, who had seen Smith find gold at Yorkey’s Corner, they turned their attention to that area and found gold nuggets to the value of £10, or $7000 in today’s money.

Hargraves returned with £10 he borrowed from a friend and bought the nuggets from the men, dissolved all partnerships and declared himself the sole discoverer.

“Despite a handsome payout of more than £12,000, he later boasted he had never done any digging himself,” Silver, author of A Fools Gold?, says of Hargraves.

“The find started the Australian gold rush and as no mineral rights had been reserved by the Crown, the gold went into the pockets of the diggers.

“The gold rush highlighted that millions of pounds in potential revenue was lost to the Crown through uncontrolled digging and the British and Colonial governments came under attack.

“Murchison, who had tried to gain interest for Smith’s find back in 1847, wrote a heated letter to the Secretary of State in London berating the government for ignoring Smith’s find, which would have given them the opportunity to control the gold rush.”

To absolve himself of any blame for local inaction, Governor Fitzroy accused Smith of trying to claim a reward using gold from California, despite the fact Smith’s nuggets sent to London had been lodged many months before the Californian rush.

This whole story is found within the letters discovered by Silver.

Smith, of whom there are no known photos, died in 1852, leaving behind a widow and six children, branded a liar and a cheat by the Colonial government.

The unveiling of the headstone this week brings the centuries-old story to an end.

“It’s fantastic that the government in 2020 is correcting a wrong from the government of 1851,” Silver said.

“It’s a nice endnote.”

DEAD CENTRE NOW A TIGHT SQUEEZE

Opened in 1867 when 18-year-old pauper John Whalan was laid to rest there, Rookwood Necropolis is Australia’s oldest and largest cemetery, in fact it’s the largest in the Southern Hemisphere and the largest Victorian-era cemetery in the world.

Since it opened, Rookwood has grown to be the final resting place for more than one million people.

But it is estimated that burial space will run out over the next 20 years, or sooner with savvy people reserving their plots ahead of time. With that in mind, there is talk for a second Rookwood in Sydney’s west or southwest.

RUSHING ALL THE WAY TO THE BANK

While a few ounces was all it took to kick off the Australian gold rush, bigger finds were to follow.

The largest gold nugget found worldwide was in the Victorian town of Moliagul where the ‘Welcome Stranger’ was found on February 5, 1869, weighing in at 66.9kg.

There were no scales big enough to weigh such a piece so it had to be broken down. Many mistakenly think the ‘Holtermann Nugget’ found at Hill End in 1872 is the biggest and at 286kg, it’s understandable why, but it wasn’t a single nugget, rather a mass of gold (93kg of it) mixed with quartz.