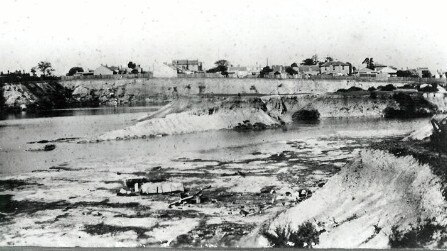

History of Sydney: Henson Park, Marrickville known as ‘pool of death’

Home to some of the most colourful stories in the rugby league game, few people know Henson Park in Marrickville is also the site of eight child drownings. The site used to be a brick pit and once it filled with rainwater, became a magnet for young boys. MORE: ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Today children play on the hill and run onto the field to kick the ball around at half time when the mighty Newtown Jets play at their home ground, Henson Park.

The Marrickville field has long been the heart of loyal inner-west rugby league fans. But few would know the grisly history of the famed ground.

Once the largest brick pit in the Inner West, Standsure Works owned by brickmaker Thomas Daley, was also one of the most deadly. It wasn’t until 1925 that the former Marrickville Council, which owned the site at the time, decided to drain and fill it in, ending the site’s grim roll call.

“Every brick pit has had children drown in them,” said Inner West historian Chrys Meader, whose father Charlie Meader was a groundsman at Henson Park from 1964 to 1994.

“Thomas Daley told a newspaper ‘where there’s a fence they scale it, where there was a hole in the fence they went through it,’ referring to the young boys who saw the waterholes as an attractive place to swim in the summer months.

“He said he dreaded the approach of summer.”

There were several brick pits that operated off Sydenham Rd in the suburbs of St Peters, Marrickville, Petersham, Camperdown and Ashfield from the late 1800s until the 1920s when the clay they sought to make bricks had run out.

The huge disused pits would fill with rainwater and became a magnet for young boys. Between 1885 and 1940 more than 60 people, mostly children, drowned in these brick pits.

Unlike today where most children have some level of swim training, children in this era often didn’t know how to swim, Meader said. The pits could be deceptive with a shallow entry that fell off suddenly to a deep drop, she added.

There were eight documented child drownings at Daley’s pit, the first of which was 11-year-old Alfred Nicoli Tremlett who drowned in January 1889 in the area known as “Blue Hole” where the Henson Park carpark and tennis courts stand today.

His home on Neville St, Marrickville backed onto the brickworks and it was said he was reaching for a duck egg when he fell in and died, just a few metres from his home.

In March 1902, 15-year-old George Dunn went to the waterhole with his younger brother after Sunday school and drowned.

In September 1905 a local family lost George Kirkland, 14, and his brother Richmond, 12, when both drowned after they went to the waterhole to fish.

On New Year’s Day 1907 Townsville boy Bartholomew Farrell, visiting his uncle for the summer, went for a swim at the pit with two friends and drowned.

From 1900 to 1907 the brickworks ceased operating as the company went into liquidation leaving the site unused and unsupervised, which accounts for the high number of drownings during this period.

But in 1909 Daley regained control of the site and the drownings stopped until 1925 when it was taken over by Marrickville Council.

In a move Meader can only refer to as strange, the council erected a dressing room at the site.

And the deaths started again.

Brothers Kerwood and Norman Bishop, aged seven and 11, were the next victims in March 1925. The older brother slipped and went into the waterhole and the younger brother attempted a rescue, but both died.

A few months later in September that year the site claimed its youngest victim. Little Trevor Austin was just five years old and had been playing at the site with his three-year-old brother and friends when he died.

Meader said the drownings of 1925 outraged the local residents who signed a petition begging council to do something about the site they called a “menace” and a “nuisance”.

A month later a local paper reported “The pool of death to go” and the lengthy project to drain and fill in the site started with the ground known today as Henson Park opening in 1933.

PLAYING A NUMBER’S GAME

If you are a Newtown Jets fan, you know exactly what the hashtag #WeAre8972 means.

The number is a tongue-in-cheek reference to the attendance number ground announcer John Lynch called at the end of a wet and miserable home game in the 1990s, a number he made up on the spot.

To this day, home games at Henson Park end with the announcement of this random attendance number.

It has become so much a part of the club, they now use the hashtag as part of their marketing and ask supporters “which number are you?”

LADIES TAKE TO THE FIELD

Before Don Bradman took to Henson Park for the start of the 1933 cricket season and before the oval hosted the Empire Games cycling events and Closing Ceremony in 1938, a team of ladies played vigoro there. Inner West historian Chrys Meader said the Dulwich Hill Wahini vigero team played on the newly laid field on December 5, 1932. “The women trotted out before the cricket opening to play a game which appears to have been a mix of tennis and cricket,” she said.

“There was no seating or dressing rooms yet and they had to ask for bubblers to be installed.”

HISTORY OF SYDNEY: STORIES OF US

WAHROONGA HOME PUTS US IN TOUCH WITH THE WORLD

You would expect an event that heralded the beginning of modern Australia to have taken place in Canberra or a prominent building in Sydney.

But the very first direct wireless message from the UK to Australia was received in a family home in leafy Wahroonga.

Today parents push prams past the grand Federation home on the corner of Stuart and Cleveland streets, unaware the home holds such a prominent place in Australian history.

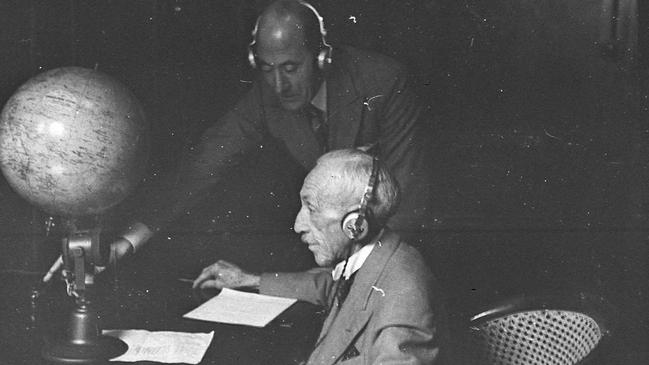

It is still privately owned today, as it was on September 22, 1918, when then-prime minister William “Billy” Hughes relayed the first direct wireless message to the home from the Marconi Station at Carnarvon in Wales.

That successful transmission would pave the way for instantaneous communication between Australia and the mother country and ultimately the world and was the forerunner to the wireless radio which would a few decades later connect most family homes with local and world events.

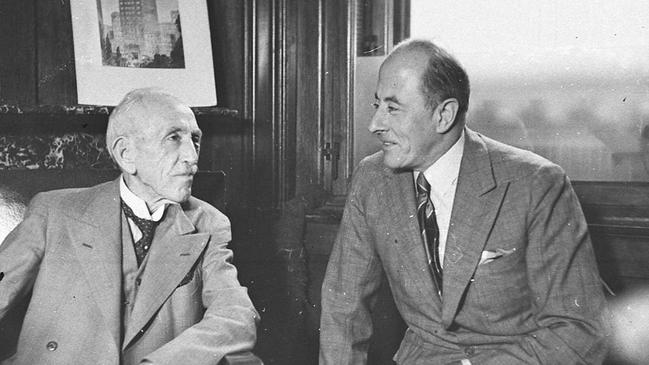

The imposing property in Wahroonga, named “Lucania”, was the family home of Ernest Thomas Fisk, a British man who came to Australia in 1911 to help introduce Marconi communication systems.

Five years later, he married a local girl named Florence and the young couple settled in their new home in Wahroonga, which was at the time a semi-rural suburb dotted with orchards and where grand homes could be built on large parcels of land.

Their home enjoyed a corner position, its gabled roofline and dormer windows a charming addition to the developing suburb. It was in the backyard of this home that technicians from Amalgamated Wireless Australasia (AWA), where Fisk was a managing director, built a 25m wooden tower with twin antennas that would transmit the famed message, along with a radio receiver set up in the home’s attic.

The tower was touted as being “experimental” at the time, but at 1.15pm on a sunny spring Sunday afternoon, the message of prime minister Hughes, who was in the UK at the time, was sent through Guglielmo Marconi.

State Library senior curator Elise Edmonds says Hughes took the opportunity on this historic occasion to push his pro-conscription message.

“I have just returned from a visit to the battlefields where the glorious valour and dash of the Australian troops saved Amiens and forced back the legions of the enemy,” the Morse Code message read.

“Filled with greater admiration than ever for these glorious men and more convinced than ever that it is the duty of their fellow citizens to keep these magnificent battalions up to their full strength.”

Up until this time, Australians received news from overseas via underwater cables, which were often delayed; from aeroplanes which would take 150 hours according to an advertisement from the time; or via ships, which took weeks.

To have messages transmitted and received almost instantaneously was revolutionary. Australia was seen as a new frontier as far as communications went, due to its distance from Europe and America, and getting wireless transmissions there was seen as the ultimate challenge.

Prior to World War I, Marconi himself — considered the inventor of the radio — wanted to visit Australia to develop his technology there but his plans were interrupted by the war.

“It would be difficult to know what Fisk’s neighbours thought about this great big tower going up in their community, but I can presume it was seen with some excitement,” Edmonds says of the home where a concrete monument was unveiled in 1935 to commemorate the event.

“In 1918 the war was coming to an end but the people had been through some tough times, this would have been an exciting event.

“The average person probably didn’t understand the technology, but they would soon understand what it could do for their day-to-day lives.”

She adds that by the 1920s wireless messaging was a lot more common and wireless stations were established by the 1930s. All this led to wireless radios, which by the start of World War II, were a common source of news gathering and entertainment in homes.

Got a local history story to tell? email Mercedes Maguire at mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

LIVE ON RADIO

Before televisions became a mainstay in Australian homes, the radio was the biggest source of news and entertainment. And it was the 1940s and the 1950s that became the golden years of radio in Australia — think of those images of the family gathered around the wireless together.

A usual day’s programming would include popular music of the day, children’s programs, news and weather updates, dramatic serial shows, housekeeping tips, quizzes, talent quests and

even music to inspire listeners to exercise.

Advertisements were also a big feature — a very similar format to the television that would soon follow.

HISTORY OF WAHROONGA

Wahroonga is the Aboriginal word for “our home” but the north shore suburb wasn’t always called this.

In the early days of settlement, it was known as Pearce’s Corner, after Aaron Pierce, a timber-getter who settled in the area in 1835. But he wasn’t the earliest settler, that honour goes to convict-turned wealthy landowner, Thomas Hyndes, who received a 2000-acre lease of land in 1822 in what is today North Wahroonga.

As industry cleared timber from the area, settlers planted orchards. The opening of the north shore rail line in 1890 attracted wealthy businessmen who built substantial homes on large blocks.

THE DAY DANCING DON STOPPED TRAFFIC IN SYDNEY

Everyone knows Sydney’s iconic ‘dancing man’, captured doffing his hat and twirling through the CBD on August 15, 1945, as the city celebrated the end of World War II.

But before him, there was another dancing man, Don Young, who stopped Sydney traffic as he foxtrotted all the way from Hurstville to Martin Place in 1928.

Young’s 23km venture, which he completed in less than three hours, may seem odd to us today, but in the late 1920s dance marathons were seen as a way to earn money and entertain the masses in a post-war world sliding towards The Great Depression.

The traffic-stopping event was captured in a Sydney newspaper with the headline “Dance through traffic” and reported that police took Young’s name seven times during the endurance event and almost scuttled his efforts with the finish line in sight.

“At Town Hall, police were not satisfied with the explanation given by the crowd,” the page five article read.

“They wanted a personal interview, so the dancer still held the girl and danced in small circles around two enormous policemen, explaining to them that he was doing it for a wager and answering numerous questions.”

As cheers went up at the end, Young claimed his 14.5-mile dance in two hours and 58 minutes beat the previous record set by a man who danced for 12 miles in two hours and 20 minutes.

Local Studies historian at Georges River Council, John MacRitchie, said Young’s attempt was one of many in the late 1920s as Australians were encouraged to participate in the craze after reading about similar cases in the US.

“There was a woman named Jean Dawson from Queensland who danced for 95 hours and then collapsed from exhaustion,” MacRitchie said.

“Also in 1928 someone danced the 50 miles from Geelong to Melbourne. And another man danced from Strathfield to Bondi accompanied by an orchestra on the back of a lorry.

“We had people like (cricketer) Don Bradman to look up to in this era but I think people were also eager to see homegrown heroes of every kind.

“It was a short-lived craze in Australia and it pretty much petered out by around 1931 as promoters weren’t around any more to publicise the events.”

The 14.5-mile foxtrot wasn’t Young’s only attempt at a dance marathon — the month before he danced to Martin Place, he set an Australasian record by dancing consecutively at Rockdale’s Palais Grande for 123.5 hours.

During the ordeal he churned through eight partners, seven pianists and two phonographs, as one broke.

In the US, dance marathons are believed to have started in 1923 when 32-year-old Alma Cummings danced for 27 hours, changing partners six times.

The craze gained pace as the world slid into the Great Depression in 1929 as it was seen as an opportunity to gain fame and fortune for the dancers and as entertainment for the viewing public.

Dancers were able to claim prizes of up to $1000, which in those days was a considerable fortune.

Dance marathons were immortalised in the 1935 book They Shoot Horses, Don’t They, which was made into a movie in 1969 starring Jane Fonda as a young woman desperate to win a Depression-era dance marathon.

By the onset of WWII, the craze had ended in the US but today hundreds of universities run dance marathons to raise money for charity.

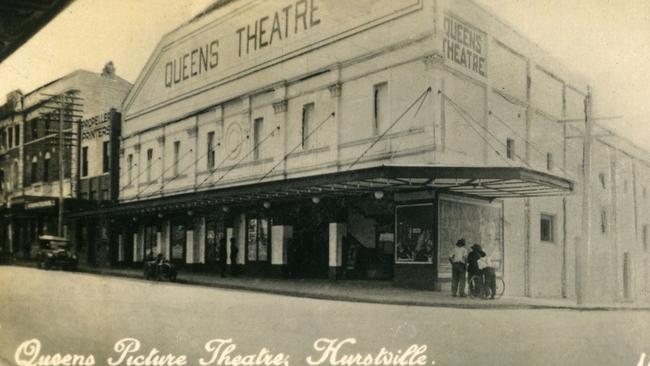

Young’s outlandish attempts turned the humble odd-jobs man into a suburban celebrity; he was reported to have made a special appearance at Queens Theatre in Hurstville to sign autographs and he was sponsored to travel to America to teach dance at the famed Roseland Ballroom in New York.

“He was the John Travolta of his era,” MacRitchie said.

“He had a beautiful, if short-lived, moment in the spotlight and then he went to the US to teach dancing. Little is known about what became of him after that but he holds a nice little piece in suburban history for his efforts.”

GOLFER’S LONGEST DRIVE

Dance marathons weren’t the only endurance craze Australians participated in during the 1920s.

John MacRitchie of Georges River Council said one man drove a golf ball from Manly to Palm Beach. And two Hurstville men, as a result of a bet, knocked a billiard ball from Penshurst to Lakemba while local boys blocked gutters along the way to prevent the ball being lost in the sewer.

“Marathons of all kinds were popular during this era,” MacRitchie said.

“People attempted endurance events by playing musical instruments, long distance swimming and even an attempt to see how long you could sit on top of a pole.”

A DANCE TO THE DEATH

Dance marathons may seem like harmless fun, but they were anything but. In the US, these early events could last days, weeks or even months. While there were rules in place — such as having a 10-15 minute break in every hour where participants went to the toilet, ate or even caught a quick catnap — the exhaustion often took its toll. One US man, Homer Moorhouse, is said to have collapsed from exhaustion after 87 hours dancing and died on the dance floor.

And in 1928, Seattle woman Gladys Lenz attempted suicide after a 19-hour dance-a-thon in which she came fifth.

* Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news. com.au