NSW history: Brazen attempt to rob gravediggers’ payroll at Rookwood Cemetery

As gravediggers toiled in the mud to exhume the bodies of American servicemen killed during World War II for relocation to the US, a brazen robbery was being plotted.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The three men who broke into the offices of Rookwood Cemetery after dark on December 11, 1947 knew exactly what they were after.

They must have known a £2000 payroll was onsite to pay the gravediggers who had worked tirelessly to exhume the bodies of American servicemen killed in the Pacific Campaign during World War II for relocation to the US.

Newspaper reports published the following day recounted the brazen attempt by the masked and armed men.

The two night watchmen on duty — George Clarke, 56, and Eric Chapman, 55, both of Lidcombe — told detectives the men were after the gravediggers’ payroll.

What they didn’t know is that the money was still in the bank and wasn’t due to be withdrawn until the following day when the gravediggers were to be paid.

A fourth man was waiting outside in a car with the engine running and the men fled without any cash. Police threw up a dragnet around the city but didn’t catch the would-be robbers.

The gravediggers had earned that money for the gruelling exhumation, which was hampered by storms that turned the soil to clay.

The bodies of 465 American servicemen were buried at the American Pavilion at Rookwood, which had been built in 1942 as a place for US servicemen to be buried during the war.

It was a grand sandstone walled rectangular parterre with a central flagstaff and could accommodate up to 800 graves. Every year from 1942-47 on US Memorial Day in May, a service was held at the American Pavilion to honour the US citizens buried there.

American servicemen had also been buried in local cemeteries around Australia, including 64 in Karrakatta, Western Australia, but in 1945 they were exhumed from their various burial grounds and reinterred at Rookwood and Ipswich Cemetery in Queensland.

The ultimate endeavour was to return the bodies to the US for permanent burial.

In late 1947, the bodies exhumed from Rookwood were taken to Brisbane by rail where they would meet 1406 of their comrades buried at Ipswich before making their way home across the Pacific.

The solemn affair on December 22 saw the single coffin of an unknown American soldier paraded through the streets of Brisbane to Newstead Wharf. State buildings flew flags at half mast as a sign of respect and workers in state offices were given an hour off in order to attend the ceremony.

A crowd of about 30,000 lined the streets to watch the cortege pass.

The coffins were placed on the US Navy transport ship Goucher Victory for their final voyage.

The attempted payroll robbery was not the first time Rookwood Cemetery was the scene of a crime.

In March 1898, caretaker of the Roman Catholic section of Rookwood Cemetery, William King, and his wife were shot and killed by Martin Cusack, a man they considered a close friend and who had worked under King for several years.

In fact, Cusack had introduced the couple and even gave Mrs King away at their wedding.

The Kings lived in a cottage onsite at the cemetery and Cusack is said to have shot them in a rage after he was let go by the cemetery trustees due to a lack of funds and insufficient work.

Cusack was named as the gunman by Mrs King who lay dying in her bed when two workers arrived the following morning. She died shortly after. Mr King was shot and died in the yard.

In December 1955, two bandits entered the offices of the Church of England section at Rookwood Cemetery and attempted to steal part of the payroll which amounted to £84. But they didn’t count on being met by the manager of the Church of England section, Arthur Scorey — a Tobruk Rat — and his assistant, Bill Lamont, who served in the AIF during World War II.

The pair tackled the men, one of whom was armed, and the bandits fled.

Got a local history story to tell? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

THE AMERICANS KEPT COMING

The first American servicemen arrived in Brisbane in December 1942 and by mid-1943 there were 150,000 stationed here, according to the Australian War Memorial. And while our love affair with American imports began during those war years (by the end of 1944 two-thirds of our imports came from the US) the disparity between the two cultures was stark.

The US military issued their servicemen with a guide to Australian culture called Instructions For An American Serviceman in Australia. It labelled us “an outdoors kind of people, breezy and very democratic” and among the friendliest guys in the world.

A MOTHER TO THE MANY LOST

The US Armed Forces Military Cemetery at Ipswich, which held the bodies of more than 1400 US servicemen who died in Australia or the region during World War II, was renamed Manson Park after the dedicated work of a local mother who tended the graves.

Rose Manson, the wife of an Ipswich mechanic and mother of eight, regularly left flowers on every grave and wreaths on the central flagpole in memory of those whose own mothers could not be there to mourn them.

She also wrote to the US families of those buried there. In August 1947, the mothers of the servicemen paid for Mrs Manson to travel to the US so they could meet her.

Lane Cove’s riverside idyll vanished in flood and fire

You’d have to close your eyes and imagine the pleasure boats rowing on the water, the families competing in sack races and ladies with bonnets enjoying a picnic on the banks of the Lane Cove River.

There’s little left of the Fairyland Pleasure Grounds in the Lane Cove National Park today, apart from a few phoenix palms, a small concrete wall and some rusted gate holders that once heralded the entrance to a bygone era.

But the picnic ground — named for the fact the spot held a magical, remote appeal — was once one of the most popular pleasure grounds in Sydney.

Robert Joshua Campbell Swan brought two blocks of land from the state government in 1896 from a parcel known as the Field of Mars Common.

The profits of this land sale was intended to finance Fig Tree Bridge, which crosses Lane Cove River at Hunters Hill.

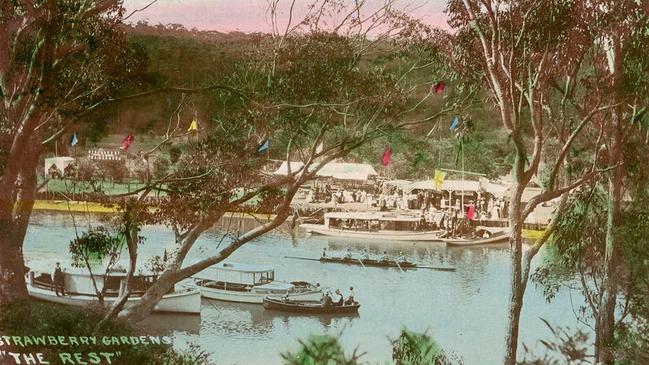

Initially, Swan cleared part of the land and operated a market garden there called The Rest, growing and selling strawberries and melon.

Tony Butteriss, president of the Friends of Lane Cove National Park, says people would stop off to buy strawberries from the Swan garden. But the market garden didn’t last and by 1910, it was being phased out.

But Swan remembered how people had enjoyed visiting his spot on the banks of the river and the idea to turn it into a pleasure ground, like those that existed in all parts of Sydney, took hold.

“There were a lot of these places around in the early 20th century,” Butteriss says.

“People wanted to go out into the bush, but not the dangerous bush, so this part of Lane Cove really appealed. They’d be able to go up the Lane Cove River in a boat and go exploring, have a picnic and enjoy a nice outing for the day.”

Initially, Fairyland was simply a popular picnic spot accessible only by ferry. But Swan began adding facilities and different types of entertainment.

To enhance his ‘fairyland’ theme, the family placed picture cards and wooden figurines of fairies and elves in the trees for visitors to spot.

And when the White City Amusement Park at Rushcutters Bay closed in 1917, Swan bought a ‘razzle dazzle’ circular ride, a flying fox and a coin-operated machine that allowed people to watch silent films through it.

Butteriss says Fairyland was a popular destination for schools, families and businesses to hold annual picnics and so Swan would hold egg and spoon and sack races to entertain visitors. When the Upper Lane Cove River Ferry Company closed in 1918, Swan purchased some of their ferries.

A dance hall was added in 1930 and part of a sandy beach was netted off to allow for safe swimming. Later an access road was built and a carpark for more than 100 cars was added.

“Fairyland was particularly popular during World War II and people would walk down from Chatswood and row across the river to attend dances there,” Butteriss says.

“But what you have to remember is that most of the buildings were quite makeshift, they weren’t substantial.”

A series of floods in the late 1960s damaged the grounds and Fairyland closed in the early 1970s as other forms of entertainment, such as movie theatres, became more popular and the growth in car ownership gave people a greater choice of weekend outings.

“These days there’s not much left there that tells you Fairyland ever existed, unless you use your imagination,” Butteriss says.

“A substantial fire that came through in 1994 took away whatever was left of the buildings.”

The land where Fairyland once existed was incorporated into Lane Cove National Park in 1978 and these days you can enjoy the site by doing the Fairyland Loop Track, a 5.3km walking trail that takes you on a round trip from Fullers Bridge in roughly two and a half hours. And it forms part of the Great North Walk that links Hunters Hill to Newcastle.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

WHITE CITY’S ROLLERCOASTER RIDE

Fairyland was one of several pleasure grounds that existed around Sydney in the early 20th century, an idea taken from Britain as a form of public entertainment for the masses.

In Sydney one of the biggest was White City Amusement Park in Rushcutters Bay which operated from 1913 to 1917 when it was struck by lightning and destroyed by fire. It was a mini city unto itself with fountains, canals and lakes throughout.

Visitors could ride the giant carousel, visit the fun factory or take a spin on the scenic railway, which had the distinction of being Australia’s first roller coaster.

RIVER’S RICH HUNTING GROUND

The Lane Cove valley was an important food source for Aboriginal people prior to European settlement, the river estuaries providing oysters, fish and crab.

After 1788, the area became an important timber source for European settlers and many wharves were built, the most important being that of ex-convict Joseph Fidden, today known as Fiddens Wharf Reserve.

The Lane Cove National Park was officially opened on October 29, 1938, in an attempt to make the foreshore land available for public recreation. A huge fire in the National Park in January 1994 destroyed about 83 per cent of the park.

How serial killer used wanted ads to lure his prey

The three men who answered Frank Butler’s newspaper advertisement in 1896 could not have known they were being lured to their deaths.

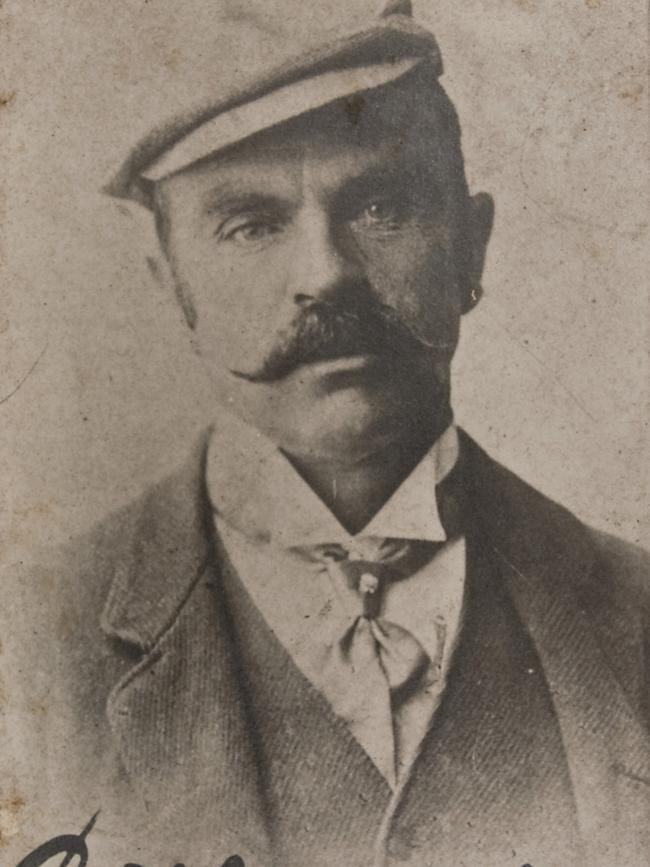

Butler was linked to the murder of Norwegian Charles Burgess, Sydney University student Arthur Preston and English sea captain Lee Weller, all of whom he enticed with the promise of finding gold.

But by the time Sydney and Newcastle police had made the gruesome connection, Butler was on a boat bound for San Francisco, sparking an international manhunt that was splashed across the front page of newspapers in several countries.

Butler was born John Newman, in England, in 1858, and later went to sea under the name of Richard Ashe, arriving in Newcastle in 1893.

Historian Michael Adams researched the life and crimes of Newman, the details of which can be heard over three episodes on his podcast, Forgotten Australia.

“He was a soldier in the British army and navy and was a deserter from the US and Canadian armies,” Adams says.

“He had a chequered past as a man of the sea and in the military.”

From Newcastle, Newman travelled to Western Australia where he stayed until 1896. While there, he raided a tent and made off with the identification papers and a mining certificate belonging to Frank Butler Horwood, a qualified miner.

In August 1896, Newman was in Sydney using the assumed name of Frank Butler and advertised in The Daily Telegraph for a mining mate to go prospecting for gold with him.

Burgess agreed to accompany Butler on the promise of half the proceeds from any mining finds. The two left on a train to Orange the next day. But a few days later, Butler was back in Sydney – alone.

He advertised a second time for a mining mate in mid-October 1896 and received a response from Preston.

“Preston was studying geology at Sydney University but he was from Brisbane and wrote frequently to his parents,” Adams says.

“He seemed like a very naive kind of guy, but he made some attempts to check Butler’s bona fides and found him acceptable, so off he went with him towards the Blue Mountains.”

A few days later, Butler again returned to Sydney by himself. By late-October, he again advertised for a mining mate and Weller agreed to accompany Butler to Glenbrook, in the Blue Mountains. A few days later, Butler was back in Sydney – alone.

In a reckless move, Butler travelled to Newcastle under the name of Weller, where the missing sea captain had arrived from England not long before. Butler signed onto a ship bound for San Francisco.

But Weller’s friends and Preston’s parents had become suspicious and told police of the advertisements the missing men answered and Butler was linked. Soon after, their bodies were found in shallow graves in the Blue Mountains, along with their possessions.

When police arrived in Newcastle, they discovered their man had gone.

As NSW was still a British colony, an extradition order could only be given on the authority and request of the British government and could only be done in person.

So, Sydney detective John Roche was dispatched, travelling to London via steamer and then on to New York and cross country to Washington and finally San Francisco, a trip he completed in 49 days.

Meanwhile, two other policemen departed on a steamer from Sydney, passing Butler’s boat in the Pacific, and arriving just ahead of him.

By the time Butler docked in San Francisco, the now front-page story meant a crowd of hundreds gathered to see him taken into custody.

Butler was detained in the city jail, where he became somewhat of a celebrity, receiving visitors, including actors, selling items of his clothing and his autograph and even being placed on public exhibition, a distinction he is said to have enjoyed.

Butler was returned to Sydney where he stood trial for murder.

On July 15, after weeks of denying his crimes, he confessed and was hanged at Darlinghurst Gaol the next day.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

Not our first serial killer

Frank Butler is often referred to as Australia’s first serial killer but he was not. Irish convict Alexander Pearce escaped his prison several times.

In one attempt in 1822, with seven others, he is said to have killed more than one of his co-offenders for food. In 1824, he was hanged for killing and eating another fellow absconder, Tomas Cox.

Then there’s John Lynch, nicknamed the Berrima Axe Murderer, who confessed to killing 10 men and was hanged in 1842. And possibly Australia’s first female serial killer, Louisa Collins, of Botany Bay, was hanged in 1889 for killing two husbands with arsenic.

Death amid the headlines

Almost 25 years before Frank Butler used newspaper advertisements to lure three men to their deaths, cell mates George Nichols and Alfred Lester did the same.

The men, who met while in jail, used a fake job ad in a Sydney newspaper in March 1872 to lure two men to their deaths.

When the men were found in possession of articles belonging to Englishman John Bridger, who was found murdered in the Parramatta River, and Melbourne teacher William Percy Walker, they were arrested.

They were executed in Darlinghurst Gaol less than three months later in June 1872.