Sad truth behind star soprano’s no-show at Sydney’s Theatre Royal in 1907

Few realised what was really going on behind the scenes the night a brave young chorus girl stepped up to save the night for Sydney opera fans.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The orchestra completed the overture to Wagner’s The Valkyrie signalling the moment the soprano would take to the stage for act two. The audience quieted in expectation of the performance about the start.

They waited and waited but nothing happened. In fact they waited a full 30 minutes, hands clapping, feet stomping, before the hold up was explained.

The audience had gathered on a cool Saturday evening in July 1907 at the Theatre Royal in Sydney to watch the visiting German Opera Company perform Wagner’s famous opera.

But instead of star Fraulein Johanna Heinze taking to the stage in the role of the war-goddess Brunnhilde, impresario George Musgrove stood before the audience and delivered the news he had tried so hard to prevent.

Fraulein Heinze, Musgrove told the waiting audience, was unable to perform as she had a cold. He had apparently offered the soprano more money, but she had demanded double her original fee and he refused to buckle to what he called blackmail.

With a full audience waiting, Musgrove was saved that night by a young chorus girl called Lilian Ormond who was not experienced enough to sing the part of Brunnhilde in The Valkyrie, but agreed to perform the role of Senta in another of Wagner’s operas, The Flying Dutchman.

Musgrove later said of the performance, “I am right in saying that she has this evening begun her career” to the loud applause of the audience.

Newspaper articles at the time gave a very detailed description of the events which led to the unusual performance, revealing the Sydney date was not the first to be cancelled due to the soprano’s supposed ill-health.

Heinze had apparently been too unwell to perform several times in the week leading up to the Valkyrie show and had sent Musgrove several letters claiming ill health. A doctor’s certificate was even produced which claimed that if she sang, she would damage her vocal chords and performances of Carmen and Hansel and Gretel were subsequently cancelled that week, costing Musgrove several hundred pounds.

One article however revealed the truth: Fraulein Heinze was not sick, but overcome with grief at the sudden news from Germany that her father had died.

This story was discovered by accident by Dani Haski, the vice-president of the Australian Jewish Genealogical Society (AJGS), as she researched the life of her great-grandfather, David Eizenberg.

Haski knew her ancestor was a talented violinist, but she did not know he was a member of the orchestra that played that fateful night when the show almost didn’t go on.

He recounted his memories of the night saying of the young chorus girl: “I’d never seen such a fine example of pluck, the girl from the chorus undertook this most difficult part and carried it through in a most credible manner. She deserved the Victoria Cross.”

Eizenberg was born in London in 1877 to Polish parents, Harris and Esther Eizenberg. The family emigrated to Australia in 1879, settling first in Brisbane before arriving in Sydney in 1898.

David was an accomplished musician from an early age, playing the violin and later offering his services as a violin teacher. He married Esther “Ettie” Diamond in 1902 and began working in her family’s estate buying business.

Newspaper advertisements announce his arrival in country towns selling goods from the estates they purchased across NSW from Bourke, Maitland and Grafton to Bathurst, Grenfell and Mullumbimby, eventually bringing his two sons into the business and establishing three shops in and around Wollongong.

Despite his business success, Eizenberg continued to work as a musician, often playing for J.C. Williamson in his productions of Floradora, Djin Djin and Australis as well as productions of Aida, The Merry Widow and Tosca and with the original Sydney Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Joseph Bradley.

He recalled playing for Dame Nellie Melba on several occasions, later calling her “the greatest singer in the world”.

Eizenberg died in 1933 of a heart attack in the Centennial Park home where he raised his three children with Ettie. He was 55.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

MELBA’S DEATH LEFT FANS BEREFT

Born Helen Porter Mitchell in Melbourne in 1861, Dame Nellie Melba, who took her name in honour of her hometown, was one of the most famous singers in the late Victorian and early 20th Century.

When she died in 1931, David Eizenberg said of her: “All music lovers feel depressed, especially those who had been associated with the greatest singer in the world.”

Her name lives on in pop culture — Melba toast and peach Melba were dishes created in her honour by French chef Auguste Escoffier and the catchphrase to have more farewells than Dame Melba refers to the soprano’s many farewell concerts.

IMPRESARIOS GAVE US THE STARS

James Cassius Williamson was born in Pennsylvania in 1845 and had some success in America as an actor.

He visited Australia in 1874 to perform in a production of Struck Oil with his wife Margaret Sullivan and the pair fell in love with Australia.

They returned a few years later with the Australasian rights to HMS Pinafore and went on to establish a successful theatrical agency in Australia.

Partnering at various times with George Musgrove and Arthur Garner, J.C. Williamson was responsible for bringing some of the biggest names in theatre to Australia, including Dame Nellie Melba, Sarah Bernhardt and H.B. Irving.

Mystery deaths of two women found 10 years apart

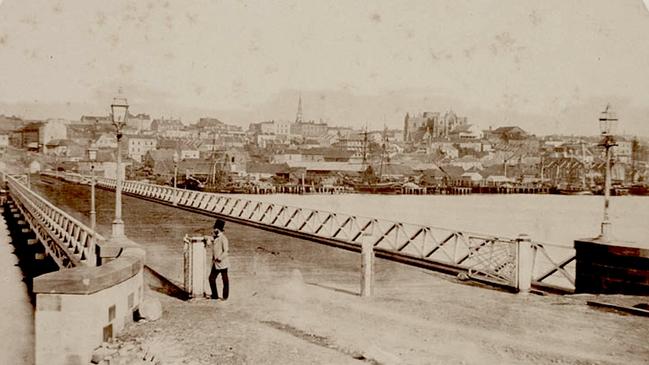

Elizabeth Walker was excited to see the new Pyrmont Bridge in Sydney when she visited her former neighbourhood in 1860.

This new structure had been built three years earlier to facilitate the movement of goods from Sydney to markets in the west and the Pyrmont woman was back home for the first time since she had married the owner of The Grafton Hotel and moved to northeast NSW.

Walker, 27, had arrived at Darling Harbour on a steamer on January 19, 1860, and that evening she set off across the bridge on foot. It was 11pm but the new bridge was lit by gas lamps. She stopped to ask a constable for directions and was also seen by a family walking on the bridge before she paid the one penny toll.

A little while later the same tollman described a long scream, followed by a short scream and then a splash and footsteps. He would later tell the Coronial Court he saw a tall man running from the scene.

The next morning, the tollman rowed a dinghy under the bridge and discovered Walker’s body face down in the water.

“There seemed to be no obvious signs of violence and she does not appear to have been raped or robbed,” says Max Burns-McRuvie, founder of tour guide company Journey Walks, who will give a talk called Murders Mysteries and Margaritas on August 4 at Sydney bar Since I Left You.

“It was initially considered a suicide and, while that couldn’t be ruled out, murder seemed the more obvious cause of death. She had £15 on her and some jewellery so robbery didn’t seem like a motive.”

A newspaper advertisement posted by Mr Walker on March 12, 1860, for the sale of his pub includes the sad end note “in consequence of the late melancholy and mysterious death of Mrs Walker, the wife of the proprietor”.

The mysterious man who fled the scene was never identified and the case went cold.

Until a decade later.

Margaret Boyce was described as a beautiful 21-year-old English woman with fiery red hair who was a common fixture walking in the Botanic Gardens, sometimes in the company of a man nicknamed The Slab, or Maggie’s Slab.

On a rare night off, Maggie went out with her brother and sister in Macquarie St and they escorted her back to the boarding house where she lived. Unbeknown to her siblings, Maggie did not return to her room and was last seen at the Robert Burns Hotel with The Slab where they drank brandy and port and were seen to be intoxicated.

The following morning, she was found face down under the Pyrmont Bridge with no obvious injuries or signs of robbery.

The date was January 19, 1870.

“It was exactly 10 years – not only to the month, week and day to the murder of Elizabeth Walker – but to the hour,” Burns-McRuvie says.

“The most senior detectives were brought in to investigate and there was a lot of speculation surrounding The Slab as a person of interest in the case.”

Jewellery thought to be missing from Boyce’s body was later found torn and in a nearby lane and her hat, a Garibaldi style popular at the time, was found on the floor of an outhouse in the backyard of a home off Sussex St.

A witness recalled seeing Boyce in the parlour of the Robert Burns Hotel in the company of a man about five foot eight inches with a dark complexion, dark moustache and wearing a black hat and dark suit.

Boyce’s sister Annie told police: “She told me that wherever she went a man was in the habit of following and watching her. I asked her how many sweethearts she had and if the tall one was (one of them). She replied that he was no sweetheart of hers and she spoke to him through fear.”

The Slab was never identified and the deaths remain a mystery to this day.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

SWING BRIDGE CLAIMED WORLD FIRST

The first Pyrmont Bridge was built in 1857 out of timber as a swing bridge which would open to allow vessels to pass into Cockle Bay near Darling Harbour.

Following a public competition to design a replacement bridge, a second structure was built out of timber with a swing span of steel between 1899 and 1902, which is the one that remains there today.

It was one of the first bridges in the world to have an electricity-operated swing span. It was closed to traffic in 1981 and remains as a pedestrian bridge.

TUMBALONG TO DARLING HARBOUR

The Eora people called Darling Harbour Tumbalong, which means “place where seafood is found”.

It identifies the area as an important source of food for the traditional custodians, the Gadigal people, and remnants of oyster shells and shellfish on the shores led to early European settlers naming the region Cockle Bay.

It became Darling Harbour in 1826, after General Ralph Darling, governor of NSW from 1825-31. An effective administrator, he is remembered as a tyrannical leader who was largely disliked.