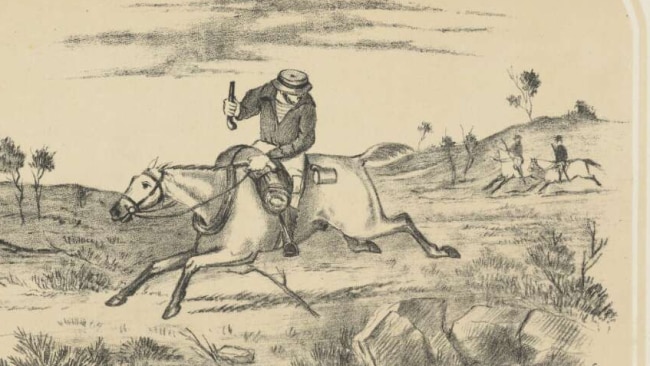

Perfect shot ended ‘Boy’ bushranger Jack Donohoe’s bold career

He was the scourge of the roads west of Sydney, until one day felon Jack Donohoe’s luck ran out in bushland near what is today the suburb of Raby.

The gangs of outlaws bailing up people along the roads west of Sydney Town had resulted in regular police patrols being implemented.

The cost of running the patrols was by far outweighed by the danger to life and property posed by these bushrangers, who seemed to be able to pop up in one place, melt into the forest and then reappear elsewhere.

One of the most notorious was John 'Bold Jack' Donohoe, an escaped felon who, living up to his name, had boldly held up two police constables at Parramatta Courthouse and locked the constables in a cell.

It was a combination of luck and cunning that helped him get away with his crimes. But, on September 1, 1830, Donohoe’s luck ran out.

A group of mounted police on patrol, near what is today Raby, were unsaddling their horses next to a creek and saw in the distance three suspicious looking men leading a horse.

Realising the men had not noticed them, policeman Sergeant Williams Hodson decided to try to sneak up close to the suspect, sending another officer across the creek, to be in a position to cut the men off should they try to escape.

Hodson got close enough to see that one of the men fitted the description of Donohoe, before he was spotted.Donohoe then cried out: “Come on, you cowardly rascals, we are ready if there’s a dozen of you.”

There was a tense standoff as both sides baited each other to fight, before one officer finally fired off a shot, which was quickly returned by the bushrangers. Police officer John Mucklestone, rated one of the best shots in the force, held back to make his shot count.

When Donohoe stuck his head out from behind a tree, Mucklestone fired his double shotted carbine. Both shots from his gun found their mark and Donohoe fell with a hole in his temple and his neck.

That was the end of the brief but eventful bushranging career of the man who inspired the song The Wild Colonial Boy.

While some were relieved at the death of a menace, others saw him as a Robin Hood figure.

He was born in Ireland in 1806. Orphaned as a boy, he took to pick-pocketing.

In April 1823 he was convicted of “intent to commit a felony” and sentenced to life. In 1824 the sentence was commuted to transportation and he arrived in Sydney in 1825 aboard the Ann and Amelia.An unruly prisoner on arrival, within a short space of time he was sentenced twice to 50 lashes.

He was then assigned to work for a private settler John Pagan at Parramatta but broke the rules and ended up on a road gang, under the watchful eye of Surgeon Major West at Quakers Hill.

In 1827 Donohoe teamed up with two other convicts, George Kilroy and William Smith, to rob travellers on the Richmond Road.

They armed themselves with pistols, often provided to convicts for protection against Indigenous warriors, and a cutlass, then stopped a bullock cart, stealing a cask of brandy, before stopping and robbing another man.

But the cart driver had recognised Kilroy, who was soon arrested. Kilroy informed on his partners in crime.

Donohoe was tried for highway robbery in 1828, convicted and sentenced to death. But he escaped and fled into the bush.

A reward of £20 offered for his capture. Six months later he was seen with a gang in Yass, robbing remote farms.

They ranged widely from Yass to Bathurst, through to the Illawarra also turning up in the Hawkesbury and on the roads between the towns around Sydney, which were then separated by large areas of bushland.

While they became the scourge of anyone who owned property or carried money or goods worth stealing along the roads of NSW, they often received help from convicts, former convicts or low-paid workers, who regarded Donohoe and fellow bushrangers as heroes.

In August 1928 he narrowly escaped when police discovered the gang’s campsite between Jugiong and Young. Several of the gang were shot dead, Donohoe fled on foot, firing pistols back at the police.

He resurfaced in November 1828 and for more than a year conducted robberies west of Sydney, eluding police.

In 1830 Governor Ralph Darling introduced the Bushranger Act to give mounted police more powers. Patrols were increased and in September 1830 police cornered Donohoe and killed him.Many celebrated the death.

One pipe manufacturer made souvenir pipes with Donohoe’s image on them including the fatal bullet holes.

Others raised him to folk hero status. In the song The Wild Colonial Boy his name was changed to Doolan, or Duggan, to avoid repercussions from police.

Many versions of the 'Boy' ballad

The Wild Colonial Boy is a ballad, or poem, penned by an anonymous writer.

It is lauded in both Ireland and Australia, which have different versions of the song.

The main difference is in the name of the protagonist outlaw; Jack Duggan in the Irish version and Jack Dolan/Doolan in the Australian. Another main difference is that the Irish version states Duggan is from Castlemaine, Ireland, but in the Australian version, Ireland is omitted.

Fatal Shore author Robert Hughes once said “there used to be as many ways of singing The Wild Colonial Boy as there were pianos in Australian parlours”.

Reverence of rogues and rebels

Why did so many stories arise around bushrangers such as like Jack Donohoe and Ned Kelly, who were ostensibly thieves and murderers?

Both Irish and both described as being Robin Hood-like characters only stealing from the rich, their status nonetheless took on legendary status which has lasted to this day.

The reason for this could be in the fact they were both seen as anti-establishment heroes against British colonial rule.

“It’s part of the Australian psyche (to be) big supporters of the underdog,” said Jo Ritale of the State Library of Victoria.

“We’re very much enamoured of rogues and rebels.”

SECRET TO A GOOD REAL ESTATE DEAL IN HURSTVILLE

The small notebook was buried under piles of rubbish in the Mittagong tip when it was found in 1984. It was missing its cover and it appeared several pages of the pocket-sized journal were also missing. But what was left of the historical document that dated from 1913 painted a charming picture of Sydney suburban life pre-WWI.

The notebook, which was given to the State Library of NSW, was a catalogue of one young couple’s search for a home in Hurstville, detailing what they paid for the block of land on the corner of Belmore Rd and Stanley St (now Australia St and Hurstville Rd); the specifications and materials needed to build their dream home and even how much they spent on tram fares visiting the site.

Sadly, the entries finish before the end of the build, but based on information included of the early stages of the process, we know Carl and Gertrude Moore built a single-storey brick cottage on the land, which they referred to as a “brick villa” and planted an impressive garden of apricot, peach and plum trees as well as roses, geraniums and other flowering plants.

The notebook also doesn’t reveal what became of the Moores in later years. But research carried out by State Library of NSW curator, Margot Riley, gives us a little glimpse into the life of the young couple.

Carl Moore married Gertrude Sinden of Lewisham in 1906. Gertrude was 22 at the time and 29 during the house hunt.

The notebook starts on January 18, 1913 with the pair looking for land to build a family home, Carl noting they got “the pick of the Claremont Estate” in reference to the new subdivision they bought into.

“It’s basically the story of a house hunting journey from more than 100 years ago,” Riley said of the notebook she came across in the State Library archives in 2019 while researching another project. “I thought it was such a treasure because the attention to detail in it and the care taken to record the process was amazing.

“I don’t think there’s another item like it.”

It details their first meeting with the vendor, a Mr Conibeere: he asks for £105 for the block, the Moores counter with £97 and they settle on £98. A further entry notes the couple go to the bank and “Gertie” withdraws £40, Carl £55 and they withdraw an additional £5 in gold. Carl goes on to note the serial numbers of all the notes he hands over.

On March 12, Carl notes his wife’s work on the garden and that the roses are “growing well”. And along the way, he notes meeting their new neighbours, a Mrs S with a horse named Ginger, a Mrs Clapson and another neighbour who asks if he may let his cow graze on their vacant block for a small fee.

We discover they were given five options for the build, ranging from £180 to £320 but, due to missing pages, we never find out which they chose.

On August 3, Carl notes he and his wife went for a walk in their new neighbourhood and spotted fibro houses he refers to as “tinpot and cheap” unlike their “brick villa”. The last page ends with fragments of further specifications on the build.

“We’re very lucky to have what we have, apart from a little surface dirt on the first few pages, it is otherwise clean,” Riley said. “But at the same time there’s tantalising facts we are missing like the conclusion of the build.

“What I love about it most though is that it shows a couple who are entering into this partnership in a balanced way, both withdrawing almost similar amounts to put towards the land, which is very modern of them.”

The couple appeared to have one daughter, born in 1918, named Marie, but no further births could be found.

Gertrude died in 1964, aged 80, and Carl died in 1972.

TRAIN PUT HURSTVILLE ON TRACK

The development of modern-day Hurstville began in the late 1800s with the opening of several key buildings. In 1881, the post office was established and in 1884 Hurstville train station opened, which spurred mass development of the area.

“With the opening of a train station on a major line, subdivision soon follows and then settlement,” State Library of NSW curator Margot Riley said.

“At the time the Moores were building their home, Hurstville was still largely rural as is evident with the mention of horses and cows in their notebook. It also mentions a tram line in the area, so in 1913, it was an emerging suburb.”

NEW OWNERS SECURE THEIR SPACE

MORE than 100 years after the Moores built their home in 1913, a Daily Telegraph article in 1916 reported the same home may well be “The most protected house in Australia.”

The brick home boasts 24 security cameras, more than 18 sensor lights, two steel-reinforced gates and electric roller shutters on the windows.

While the Moores constructed their home with all the romantic hope for their future, the current owners appear to be guarding against Sydney’s growing crime rate.

“We don’t want to move, this is our home,” owner Julie Saikaly said at the time. “That’s why we spent all the money on the cameras.”

Marriage scandal inspired woman ahead of her time

By Mercedes Maguire

If you wander around Waverley Cemetery you will likely see the gravesite of Aussie poet Henry Lawson, as well as that of cricketer Victor Trumper and Australia’s first prime minister, Edmund Barton.

But unless you have an exact plot number and a map, you won’t find the final resting place of Jeannie Lockett, who died in 1890, as she was buried in an unmarked grave.

If she did have a headstone, though, it would likely tell of her pioneering efforts in Australia’s teaching industry and the fictional stories she wrote, many of which were published in Australian newspapers.

Jeannie Lockett was born in Bathurst in 1843 and she later moved to Wagga Wagga where she met and married blacksmith Thomas Lockett in 1868 from her parents house.

The young couple had three children and soon after the birth of her third child, she appeared in court as a witness in what would have been a scandal in the small regional town.

“Jeannie and Thomas had a servant girl of 17 called Annie Blake working for them for a few weeks when she became pregnant and tried to commit suicide by swallowing arsenic,” historian and author Caroline Hardy says of the 1873 event.

“She asked Jeannie one afternoon if the pharmacy was open and Jeannie asked the girl if she was feeling okay.

“The young girl walked into town, bought the arsenic and went into her room, where Jeannie later heard crying and discovered Annie taking the poison.

“The chemist would tell the court she had asked for strychnine but he wouldn’t sell it to her, so she bought the arsenic instead, which was then commonly sold as household rat poison.”

The testimony followed that three doctors attended the premises and gave Annie salt water to induce vomiting. Police also attended and Annie was arrested because at the time suicide attempts were illegal.

“It was big news at the time and a bit of a scandal on a couple of fronts,” Hardy says.

“Anyone putting two and two together would have wondered if the husband was involved (in the servant girl getting pregnant). And soon after Jeannie leaves town with her three children, all aged under five, and moves to Sydney.

“It must have been tough for a single mother trying to make a living during this time whilst caring for three young children.

“But she must have done a decent job of it because her eldest child, George, became a successful dentist which would have required a good education.”

Lockett was accepted as a student teacher in 1877. The profession was undergoing revolution of sorts during this time and becoming more regulated. Up until this point, lots of schools were run by churches who did not follow a strict curriculum and there were no official qualifications needed to be accepted into the school system.

Lockett rose to the level of head mistress in Sydney’s inner city suburbs and also had a few opinion pieces published in the Westminster Review in England.

Hardy says these pieces appeared to have been influenced by her early experiences as they were on the topic of divorce.

She argued that divorce legislation was formulated by men claiming marriage is for keeps, which she said showed a lack of awareness of a woman’s point of view or of her needs.

Interestingly, Lockett never divorced her husband, she merely left him. She also had a series of fictional stories serialised in Australian newspapers with headings such as The Millwood Mystery, The Case of Dr Hilston, The Garston House Tragedy and An Awfully Sudden Death.

Her first novel, Judith Grant, which opens with a suicide attempt, was published posthumously in 1893.

In her later years, Lockett was again visited by controversy, this time within her teaching career, where she was accused of bullying a member of staff and neglecting the student teachers she was responsible for and she was demoted.

Others however claimed Lockett had made a wonderful contribution to the teaching industry.

She died of gastritis at St Vincent’s Hospital in 1890. She was 43.

Got a local history story to share? email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

DESPERATE ANNIE’S SAD FATE

The story of young Annie Blake became a side note in that of Jeannie Lockett but an interesting one just the same. Annie was charged with the offence of attempting to take her own life and went to court.

In February 1873 she was found guilty and committed to spend a year in Goulburn Jail. Interestingly, suicide and attempted suicide were treated as a crime in NSW until 1983.

And there are still many countries around the world that consider it a criminal offence, including Malaysia, Saudi Arabia and many African nations.

MAKING A NAME FOR HERSELF

In Lockett’s time it was not uncommon for well-educated women to earn a living as published authors, though often under an assumed name. Lockett bucked this trend by always writing under her own name.

In the early to mid-1800s Scottish-born Catherine Spence, for example, wrote under her brother’s name or the generic “A colonist of 1839” because female writers attracted a stigma.

By the 1880s in Australia, there were many female journalists but they were confined to the social pages, ‘agony aunt’ columns and household hints sections.

TEA KING’S GHOST STILL HAUNTING THE QVB

Mei Quong Tart sat counting his takings after a long, busy day at his Elite Hall tea rooms in the Queen Victoria Building.

It was late at night in August 1902 and he was one of the few people left in the Romanesque building that had opened only four years earlier.

He probably sat in happy reflection of his success, the tea importation business he started in the 1880s had led to three tea rooms in Sydney and he was a popular figure known to everyone from the poorest residents whom he helped through his philanthropy to the wealthiest in society who sought out his exquisite fine tea, said to be the best in the city.

But on this evening, Quong’s end-of-day process was interrupted when Frederick Duggan broke into his office on level one and bludgeoned him with an iron bar.

He was left for dead and discovered by his wife and eldest daughter hours later, still alive.

But he would never fully recover from the wounds inflicted that evening and died less than a year later.

The office where Quong was attacked is today in the vicinity of the Anna Thomas store and while his ghost is said to inhabit the building it has always been reported as a friendly presence, sometimes seen waving and welcoming guests to the retail building.

Quong was born in China in 1850 and arrived in Sydney aged nine with his uncle who was lured by the goldfields.

Guest Experiences manager at the QVB, John Burdon, tells the story of how Quong was left with a Scottish storekeeper while his uncle went off to find his fortune.

“When he was around 14, the well-to-do Simpson family came into the store and the wife was so enamoured with this young Chinese boy who spoke English with a Scottish accent, that they took Quong into their home and pledged to give him every opportunity in life,” says Burdon, who also runs tours of the QVB.

The Simpsons had several gold claims and they gave one to Quong, which he used to set himself up in business.

In 1881, he returned to China for a visit and while there, established an importation business with his brothers who remained in China.

“He set himself up selling silk and tea around Sydney and he became popular, his tea rooms were the first such business in Sydney,” Burdon says.

“The most famous was the Loong Shan Tea Shop on King St, which he opened in 1889, a block north of where the QVB would soon be built.

“He was popular because he brought tea to society, there had been nothing like his tea rooms before. When the QVB was being built, the owners were keen to have his tea rooms in the building, they thought he would be a major drawcard.”

Quong established two large tea rooms in the QVB shortly after it opened. His facilities took up half of the ground floor and half of an upper floor and they were connected by a plush red carpet in the area that today houses the concierge’s office where Burdon works.

The Elite Hall tea rooms on the upper level had a capacity for 500 people. Off his tea rooms Quong established a ladies gymnasium, where women could do callisthenics, as well as a ladies reading room.

The tea rooms were a grand affair with plush decor, fountains, ferneries and a fish pond.

Quong was a beloved figure in Sydney well known for his philanthropy for poor children, women’s rights and as an important spokesperson for the Chinese Australian community.

He died of pleurisy at his home in July 1903. Two hundred members of the Chinese Australian community escorted his coffin from his home in Ashfield to the train station and on to Rookwood where he was buried in a funeral attended by thousands as well as his beloved wife, Margaret Scarlett, and their six children.

Got a local history story to share? email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

TEA AND SYMPATHY FOR SUFFRAGETTES

The Womanhood Suffrage League of NSW used Mei Quong Tart’s Loong Shan Tea Shop as their unofficial headquarters in the 1890s, says guest experiences manager at the QVB, John Burdon.

“They really had nowhere else to meet, so his early support of the group was important to them,” he says.

“When Quong opened his tea rooms in the QVB, the suffragettes would hold their meetings and rallies there and they would also meet to do martial arts in the ladies gymnasium.”

Quong lived long enough to see women in NSW gain the right to vote in 1902.

DIGNITARIES’ DOME WITH A VIEW

When the Sydney Harbour Bridge opened in 1932, dignitaries gathered to watch the official proceedings from the comfortable distance of the QVB dome, away from the masses on the bridge.

At the time, the QVB dome was considered the highest point on the Sydney skyline.

Likewise, during WWII the upper dome of the QVB was used as a lookout by soldiers who were able to see any potential invaders entering through Sydney Harbour.

The lower levels of the QVB were used as a meeting point for Australian navy officers during the war, who also kept their personal belongings there while on shore leave.